http://invokingthegoddess.lk/gallery/

http://invokingthegoddess.lk/gallery/

http://invokingthegoddess.lk/category/photo-essays/

Intro

Devotion to Kannaki-Pattini is an inspiring example of Hindu-Buddhist syncretism in Sri Lanka. The goddess is revered by many Tamil Hindu and Sinhala Buddhist Sri Lankans, though rituals and practices of veneration vary between the two religions, and regionally. Ironically, a significant number of Sri Lankans are unaware that she is a shared deity – an indication perhaps of the extent of the alienation between the two main ethnic communities in this small island nation. Tamil Hindus know her as Kannaki and Sinhala Buddhists as Pattini.

Pattini-Kannaki is also a fascinating and complex example of womanhood. On the one hand, she remains the chaste and loyal wife of Kovalan, despite his unfaithfulness and betrayal. But on the other hand, she is the outraged and vengeful widow who tears out her left breast and sets alight an entire city in her determination to redress injustice.

In a context where Sri Lanka is slowly emerging from three decades of civil war, and attempting to stitch together a social fabric tragically bifurcated into triumphant Sinhalese and defeated Tamils, it is timely to reflect on the shared history and traditions of Sinhalese and Tamils, Buddhists and Hindus.

As a sorrowing yet resilient woman who punishes but also offers succour to multitudes, Kannaki-Pattini is a symbol of hope to the many war widows and women-headed households now constituting a large percentage of the population. This hope is most poignantly articulated in Marilyn Krysl’s short story about Rajeswary from Batticaloa who weathered unimaginable suffering until the tsunami bore her away: http://www.guernicamag.com/features/fire_inside/

History

Pattini, which means ‘faithful and chaste wife’ in Sanskrit, is worshipped in her original form of Kannaki/Kannakai Amman or Mother, the fearless protagonist of the South Indian epic Silappadikaram (The Tale of an Anklet), by Sri Lankan Hindus, particularly in the island’s eastern and northern regions. Devotees in these regions believe that Kannaki, after destroying the city of Madurai in retribution for the execution of her husband falsely accused of stealing the Queen’s anklet, crossed over to Lanka in order to cool down and visited two places in the north and seven places in the east of the island, all of which now have important kovils (temples) to Kannaki Amman (see also http://www.dailynews.lk/2001/pix/PrintPage.asp?REF=/2010/10/12/fea09.asp).

Pattini, which means ‘faithful and chaste wife’ in Sanskrit, is worshipped in her original form of Kannaki/Kannakai Amman or Mother, the fearless protagonist of the South Indian epic Silappadikaram (The Tale of an Anklet), by Sri Lankan Hindus, particularly in the island’s eastern and northern regions. Devotees in these regions believe that Kannaki, after destroying the city of Madurai in retribution for the execution of her husband falsely accused of stealing the Queen’s anklet, crossed over to Lanka in order to cool down and visited two places in the north and seven places in the east of the island, all of which now have important kovils (temples) to Kannaki Amman (see also http://www.dailynews.lk/2001/pix/PrintPage.asp?REF=/2010/10/12/fea09.asp).

Not surprisingly, there are many claims and counter-claims regarding the specific sites in the North and East that were visited by Kannaki. Some devotees in the North claim that Kannaki first stepped onto Lankan soil at Jambukola Pattinam (now Sambuturai) and rested at Sudumalai (the Kannaki kovil here has been re-named Bhuwaneshwari Amman Kovil) and Mattuvil (site of the renowned Panrithalachi Kannaki Amman Kovil) before heading East. Other devotees believe that Kannaki, broken hearted at Kovalan’s second betrayal (after she pieced together his body parts, sewed them up and brought him back to life, he arose uttering Madhavi’s name), assumed the form of a five-headed Naga (cobra) and sought sanctuary in Lanka. She first stopped at Nainateevu and then proceeded to Seerani, Anganam Kadawai, Alavetti and Suruvil (interestingly, this route incorporates sites where shrines to Naga deities currently exist). Another group of devotees, while agreeing that Kannaki first arrived in Nainativu in the form of a cobra, insist that she then proceeded to Kopay, Mattuvil, Velambirai, Kachchai, Nagar Koil, Puliyampokkanai and finally, Vattrappalai.

Some devotees in the east claim that she stepped onto Lankan soil at Vantharamoolai, which means ‘place of arrival’ and finally took up residence in the forest in Koraveli (Kiran) because she found other shrines in the midst of human settlements too noisy. However, the majority of the devotees and ritual practitioners in both the North and East are in agreement that the 10th place she visited was Vattrappalai, in the Mullaitivu district. This belief is given further credence through the argument that Vattrappalai is a corruption of its original name Patthappalai: pattham – tenth and palai – resting place.

The popular belief among Buddhists in Sri Lanka is that the worship of Pattini Maniyo or Mother, was introduced to the island in 2nd Century AD. They often quote the historical narrative of kingship, The Rajavaliya (probably written in the 17th century), which notes that when King Gajabahu rescued 12,000 Lankan prisoners (and took an additional 12,000 Cholans as prisoners) from the Chola Kingdom (present-day Tamil Nadu), “he also took away the jewelled anklets of the goddess Pattini and the insignia of the gods of the four devala, and also the bowl-relic which had been carried off in the time of king Valagama” (1900: 48).

The popular belief among Buddhists in Sri Lanka is that the worship of Pattini Maniyo or Mother, was introduced to the island in 2nd Century AD. They often quote the historical narrative of kingship, The Rajavaliya (probably written in the 17th century), which notes that when King Gajabahu rescued 12,000 Lankan prisoners (and took an additional 12,000 Cholans as prisoners) from the Chola Kingdom (present-day Tamil Nadu), “he also took away the jewelled anklets of the goddess Pattini and the insignia of the gods of the four devala, and also the bowl-relic which had been carried off in the time of king Valagama” (1900: 48).

Some devotees and ritual practitioners amalgamate this event with those mentioned in theSilappadikaram by claiming that Gajabahu then built a devale (temple) in his capital where he deposited the anklet. He is also credited with inaugurating the first perahera, which circumambulated his capital city with the anklet, in order to venerate Pattini. These events are mentioned in what is now believed to be an ancient editorial comment inserted in the Silappadikaram: “Gajabahu of Lanka … built a temple with a sacrificial altar for Pattini to whom daily offerings were made. Thinking, ‘She will end hardship, and bestow favors,’ he established an annual festival in the month of Adi. Then, it rained without interruption: the crops never failed, and the land overflowed with abundance” (Parthasarathy 1993: 278; see also Rasanayagam 1984: 73).

Certain ritual practitioners also associated the water cutting ceremony performed at all Pattini devales as well as the Temple of the Tooth Relic in Kandy (usually after their annual perahera) with commemorating King Gajabahu’s journey to the Chola Kingdom – he parted the ocean by striking it with an iron mace and thus walked across to the Chola capital. This event is recounted in the Gajaba Katava, which is sometimes performed during Gammaduwa(village hall) ceremonies (Obeyesekere 1978).

Certain ritual practitioners also associated the water cutting ceremony performed at all Pattini devales as well as the Temple of the Tooth Relic in Kandy (usually after their annual perahera) with commemorating King Gajabahu’s journey to the Chola Kingdom – he parted the ocean by striking it with an iron mace and thus walked across to the Chola capital. This event is recounted in the Gajaba Katava, which is sometimes performed during Gammaduwa(village hall) ceremonies (Obeyesekere 1978).

Pattini is the only female deity who is accorded a place of honour within the Sinhala Buddhist (Theravada) pantheon. She is considered to be one of the four guardian deities of Sri Lanka (hatara varam deviyo) and is represented in the annual Asela Perahera, the most sacred and important Buddhist pageant in the country, which conveys the tooth relic of the Buddha around the city of Kandy, in August.

Pattini is also the goddess of fertility and health, a guardian of Buddhism and a bodhisattva aspiring (perum puranava) to attain Enlightenment or Buddhahood.

Some of the devotional claims by Hindus and Buddhists are also overlaid by scholarly claims. For example, several scholars have argued that King Gajabahu returned to Lanka, with Kannaki’s anklet, via Jambukola Pattinam, and that his first stop was at Anganamai Kadavai where he built a temple for her (Sukumar 2009; Krishnarajah 2004; Rasanayagam 1926; Satkunam 1976; Sittrambalam 2004; Sivasubramaniam 2003). This assumption is supported by the argument that the oldest Kannaki kovil in the island is located here and that a colossal statue of a king, presumably Gajabahu, had been built facing this temple. This statue, according to Rasanayagam (1926), was broken by an elephant over a century ago, and P.E. Pieris Deraniyagala who later discovered its head and feet in the kovil premises, deposited these fragments in the Jaffna Museum.

Like many devotees, several of these scholars have also conflated the two events mentioned in the Rajavaliya and Silappadikaram assuming that Gajabahu’s plunder of Chola treasures and the capture of prisoners occurred when he attended the consecration of the first shrine to Pattini in the Chera Kingdom of King Senguttuvan. This compounding of errors is exemplified in Aryadasa Ratnasinghe’s article in the Sunday Observer of 11th January 2004:

The Pattini cult was brought to Sri Lanka from South India by king Gajabahuka Gamani (112-134), along with the gold anklet of the goddess, a statue of hers, together with the statues of gods Vishnu, Skanda and Natha, whe n he returned to Sri Lanka with 20,000 Cholians plus the 20,000 Sinhalese, taken as captives to India, by the Cholian king who invaded the island during the reign of Vankanasikatissa (109-112). King Senguttuvan compromised with king Gajabahuka Gamani, to send an equal number of Cholians together with the 20,000 Sinhalese.

n he returned to Sri Lanka with 20,000 Cholians plus the 20,000 Sinhalese, taken as captives to India, by the Cholian king who invaded the island during the reign of Vankanasikatissa (109-112). King Senguttuvan compromised with king Gajabahuka Gamani, to send an equal number of Cholians together with the 20,000 Sinhalese.

Devotees and religious practitioners at Thambiluvil Kannaki Amman temple (who consider this temple to be the most ancient) claim that King Gajabahu brought three sandalwood statues of Kannaki, made under the supervision of the ruler of the Chera Kingdom, King Senguttuvan, and landed at the port of Tirukkovil which in those days was called Naga Munai as it was thickly forested and peopled by the Naga tribe. He built a shrine for Kannaki at Urakkai (a short distance from Thambiluvil) and gifted one of the statues to this temple. Gajabahu picked this location because a pigeon rose from the underbrush calling out ‘kannaki, kannaki’ when he was walking in the forest. The shrine at Urakkai, along with the statue, was later moved to Thambiluvil.

Some scholars argue that King Gajabahu also ordered the building of temples to Kannaki all over Lanka and that is the reason for the proliferation of her cult across the island, be it in the form of devotion to Kannaki or Pattini (Rasanayagam 1926; Satkunam 1976). Indeed, the Thambiluvil Ursuttri Kaviyammentions that there is a Kannagi Amman kovil in every village in the Batticaloa district (Satkunam 1976; Sittrambalam 2004). Currently, there are more than 60 Kannaki Amman kovils in the Eastern Province. Thirty of these are mentioned in the Thambiluvil Ursuttri Kaviyam (however, the first one that is mentioned, Anganam Kadawai, is located in the Jaffna peninsula) while an additional six are mentioned in the Pattimedu Ursuttri Kaviyam. Many of these temples are perceived to have been built in the latter part of the 18th century and early 19th century (Virakesari, June 2 2012).

However, Gananath Obeyesekere has disputed many of the above-mentioned claims and assumptions. We will not re-hash here all the detailed arguments he made in the article, ‘Gajabahu and Gajabahu Synchronism: An Inquiry into the Relationship Between Myth and History’ (1978), but only wish to highlight two interesting points:

(1) While an older tradition such as the water cutting ceremony may have become associated with Goddess Pattini, in later years, the bringing of the anklet to Sri Lanka by King Gajabahu is more likely a myth, rather than a historical fact, that was improvised in later years to explain the prevalence of South Indian settlements in the hill country – the Rajavaliyaends the account about Gajabahu by mentioning how he “caused the supernumerary captives to be distributed over and to settle in these countries, viz., Alutkuruwa, Sarasiya pattuwa, Yatinuwara, Udunuwara, Tumpane, Hewaheta, Pansiya pattuwa, Egoda Tiha, and Megoda Tiha” (1900: 48-9).

(2) While King Gajabahu is mentioned in the 4th century historical chronicle, Dipawamsa, and the 5th century historical chronicle,Mahawamsa (both written in Pali), there is no reference to him making such an important visit to the Chera Kingdom as mentioned in theSilappadikaram. The Mahawamsa also makes no mention of a Pattini cult in Lanka which suggests that it was only introduced some time after the 5th century as later historical texts written in Sinhala such as theRajaratnakara (16th century) and Rajavaliya (17th century) mention such a cult. Therefore, a more plausible inference is that the Pattini cult was introduced to Lanka, some time after the 10th century, by colonists from Kerala.

(2) While King Gajabahu is mentioned in the 4th century historical chronicle, Dipawamsa, and the 5th century historical chronicle,Mahawamsa (both written in Pali), there is no reference to him making such an important visit to the Chera Kingdom as mentioned in theSilappadikaram. The Mahawamsa also makes no mention of a Pattini cult in Lanka which suggests that it was only introduced some time after the 5th century as later historical texts written in Sinhala such as theRajaratnakara (16th century) and Rajavaliya (17th century) mention such a cult. Therefore, a more plausible inference is that the Pattini cult was introduced to Lanka, some time after the 10th century, by colonists from Kerala.

Obeyesekere further consolidates these arguments in his tome, The Cult of the Goddess Pattini (1984). Surprisingly, such a startling refutation of such long-held assumptions seem to be unknown to, have been ignored or misunderstood by most scholars, ritual practitioners and devotees.

Take for example, the website: http://karava.org/religious/the_pattini_cult, that claims Gajabahu as a “Karava king” and faults “historians with other motives” for misidentifying him as Gajabahu I rather than Gajabahu II who ruled in the 12th century – Obeyesekere noted that the 12th century was “palpably too late a date” to associate with the writing of the Silappadikaram (1984: 363). It also ascribes the events mentioned in the Rajavaliya to theSilappadikaram. Ironically, the website offers fodder for Obeyesekere’s thesis by noting that the Karavas (who originated from Kerala) still retain clan names such as Pattini-Hennadige while some ancestral Karava homes are referred to as Pattini Gederas.

The programme note for the evocative dance drama, Mekala, adapted from the epics Manimekhalai and Silappadikaram by renowned choreographer Arunthathy Sri Ranganathan, in October 2013, emphatically noted: “The introduction of Pathini cult by King Gajabahu II in Sri Lanka cannot be a myth.”

Balasukumar (2009) while reiterating the Rajavaliya narrative to explain provenance of devotion to Pattini among Sinhala Buddhists, nonetheless offers an alternative theory regarding devotion among Tamil Hindus. According to him, when poet Ilango Adigal wrote the Silappadikaram in 2nd century AD, he incorporated much older stories that had been recounted by Tamil natives (a similar argument is also made by Satkunam 1976). During this time, Lanka was part of India and when it separated from India due to geological changes, the story about Kannaki as well as devotion to her remained in Lanka. Seneviratne (2003) seems to be the only scholar who implicitly addresses some of the doubts raised by Obeyesekere by suggesting the possibility of Sinhala texts such as the Pantis Kolmura evolving from a folk tradition that existed in South India during the medieval period, as they reflect a mixture of Sinhala and Tamil traditions.

Balasukumar (2009) while reiterating the Rajavaliya narrative to explain provenance of devotion to Pattini among Sinhala Buddhists, nonetheless offers an alternative theory regarding devotion among Tamil Hindus. According to him, when poet Ilango Adigal wrote the Silappadikaram in 2nd century AD, he incorporated much older stories that had been recounted by Tamil natives (a similar argument is also made by Satkunam 1976). During this time, Lanka was part of India and when it separated from India due to geological changes, the story about Kannaki as well as devotion to her remained in Lanka. Seneviratne (2003) seems to be the only scholar who implicitly addresses some of the doubts raised by Obeyesekere by suggesting the possibility of Sinhala texts such as the Pantis Kolmura evolving from a folk tradition that existed in South India during the medieval period, as they reflect a mixture of Sinhala and Tamil traditions.

Under Portuguese rule the ancient Pattini Déváles in the western coast of the Kotte kingdom had been replaced by St. Anne’s churches whilst St. Marys’ replaced Máriamman Kóvils. Some of the St. Anne’s churches coming from Portuguese times are at Wattala, Bolawalána Negombo, Palangaturai and Talawila. St Anne’s Kochchkade north of Negombo is significant as it is located in Palangaturai, the harbour named in honour ofPalanga, the consort of goddess Pattini.

However, what is undisputed is that devotion to Kannaki-Pattini, while declining somewhat over the centuries, continues to flourish in the Eastern Province and to a lesser extent in the Northern, North Western, North Central, Central, Uva, Sabaragamuwa and Western Provinces of Sri Lanka. Her kovils and devales have survived despite being plundered and burnt by Portuguese and Dutch colonists and many of her devotees being excoriated and/or converted by Christian missionaries of various denominations.

Both Buddhist and Hindu devotees we met mentioned that the revered Catholic shrine to the Virgin Mary at Madhu was originally a Kannaki-Pattini shrine.

This belief is confirmed by Ragupathy (1987) as well as British civil servant, R.W. Ievers’ Manual of the North-Central Province, Ceylon (1899): “At the present day the offerings are generally taken to St. Mary’s Church at Madu, which is considered by the Buddhist and a great many of the Tamil pilgrims, who resort there, as the Temple of Pattini Amma (Amman Kovil).” Obeyesekere notes that he interviewed Buddhists “who visit the Madhu shrine during the annual festival, and they simply believe they are worshipping the goddess Pattini” (1984: 480).

Devotees had also pointed out the Saint Sebastian Church near Colombo as also being a former shrine to Pattini (Ibid) whilehttp://karava.org/religious/the_pattini_cult makes the following claim:

[some text missing here? Editor]

In later years, nationalist, religious reformers/revivalists such as Arumuga Navalar and the Anagarika Dharmapala also sought to abolish the worship of subordinated, animistic, non-agamic (non-Sanskritic/Brahamanic) deities like Kannaki-Pattini whom they believed were polluting the purity of Hinduism and Buddhism. Navalar was severely critical of Kannaki and branded her as a Jaina Merchantess – “Camana Camaya Cetticci” (quoted in Ragupathy 1987), leading many temples dedicated to her in the North to re-name themselves as shrines to Durga, Rajarajeshwari, Bhuwaneswary and Parashakti and to re-structure their architecture and rituals according to agamic (Sanskritic) principles. Several Kannaki Amman temples in the Wanni that were either damaged or destroyed during the war have also sought to re-build according to agamic principles and have recently been taking out full-page advertisements in Tamil newspapers to announce their kumba abishekam (consecration). Videos of these rituals are also posted on the internet so that devotees in the diaspora (who are often the funders of such renovations) can stay abreast of major events occurring at their (former) local temple:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aZcfA_dRrVs.

In later years, nationalist, religious reformers/revivalists such as Arumuga Navalar and the Anagarika Dharmapala also sought to abolish the worship of subordinated, animistic, non-agamic (non-Sanskritic/Brahamanic) deities like Kannaki-Pattini whom they believed were polluting the purity of Hinduism and Buddhism. Navalar was severely critical of Kannaki and branded her as a Jaina Merchantess – “Camana Camaya Cetticci” (quoted in Ragupathy 1987), leading many temples dedicated to her in the North to re-name themselves as shrines to Durga, Rajarajeshwari, Bhuwaneswary and Parashakti and to re-structure their architecture and rituals according to agamic (Sanskritic) principles. Several Kannaki Amman temples in the Wanni that were either damaged or destroyed during the war have also sought to re-build according to agamic principles and have recently been taking out full-page advertisements in Tamil newspapers to announce their kumba abishekam (consecration). Videos of these rituals are also posted on the internet so that devotees in the diaspora (who are often the funders of such renovations) can stay abreast of major events occurring at their (former) local temple:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aZcfA_dRrVs.The greatest storm weathered by devotion to Kannaki Amman, primarily in the North and East, was the three decades of war that traumatized, maimed and killed devotees, ritual performers and ritual practitioners and damaged or destroyed places of worship (for a list of these kovils, compiled by the Tamil Centre for Human Rights, see: http://www.tchr.net/religion_temples.htm). Kannaki Amman kovils were abandoned as populations fled shelling, the advance of troops or the declaration of High Security Zones. They were desecrated due to rapes that took place within them and were shunned by those who felt that she had abandoned them. Annual festivals at her shrines became occasions for forced conscription. However, her shrines were also places of refuge to those who were displaced, tortured, made mad with grief, and to those whose only recourse was to seek divine intervention when all else had failed.

References

Gunasekera, B (ed). 1900. The Rajavaliya. Colombo: Government Printer.

Gunasoma, Gunasekera. 1996. An Keliya: Panam Pattuva Asuren. Kottawa: Sara Publications.

Ievers, R.W. 1899. Manual of the North-Central Province, Ceylon. Colombo: Government Printer.

Knox, Robert. 1681. An Historical Relation of the Island of Ceylon in the East Indies. London: Chiswell.

Krishnarajah, S. 2004. ‘Ilaththu Amman Aalayangal Oru Varallatru Parvei’ Thillampathy Sri Sivakami Ambal Aalayam Kumbabishekam. Kondavil, Yalpannam.

Obeyesekere, Gananath. 1978. ‘Gajabahu and Gajabahu Synchronism: An Inquiry into the Relationship Between Myth and History’ in Religions and Legitimation of Power in Sri Lanka, ed., Bardwell Smith. Chambersberg, PA: Anima Books.

—————————— 1984. The Cult of the Goddess Pattini. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Parthasarathy, R (trans). 1993. The Cilappatikaram of Ilanko Adigal. New York: Columbia University Press.

Ragupathy, Ponnampalam. 1987. Ancient Settlements in Jaffna. Madras: Thillimar Ragupathy.

Rasanayagam, Mudaliyar C. 1926. Ancient Jaffna. Madras: Everymans Publishers Ltd.

Satkunam, M. 1976. ‘Ilanthil Kannaki Valippattin Thottrmum Valarchiyum’ Thiruketheeshwaram Thirukirada Thirumanjana Malar. Thiruketheeshwaram: Thiruketheeswaram Aalaya Thirupani Sabai.

Seneviratne, Anuradha. 2003. Anusmrti: Thoughts on Sinhala Culture and Civilization, Volume 1. Wellampitiya: Godage.

Sittambalam, C.K. 2004. ‘Silambu Padivu Seithulla Amman Valiyadu’ Thillampathy Sri Sivakami Ambal Aalayam Kumbabishekam. Kondavil, Yalpannam.

Sivasubramaniam. 2003. ‘The Traditions of Kannaki Worship in Batticaloa.’ Paper presented at the Second World Hindu Conference. Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Sukumar, Bala. 2009. Ilanthil Kannaki Kalacharam. Chennai: International Institute of Tamil Studies.

Warrell, Lindy. 1990. Cosmic Horizons & Social Voices. PhD Dissertation submitted to the Department of Anthropology, University of Adelaide.

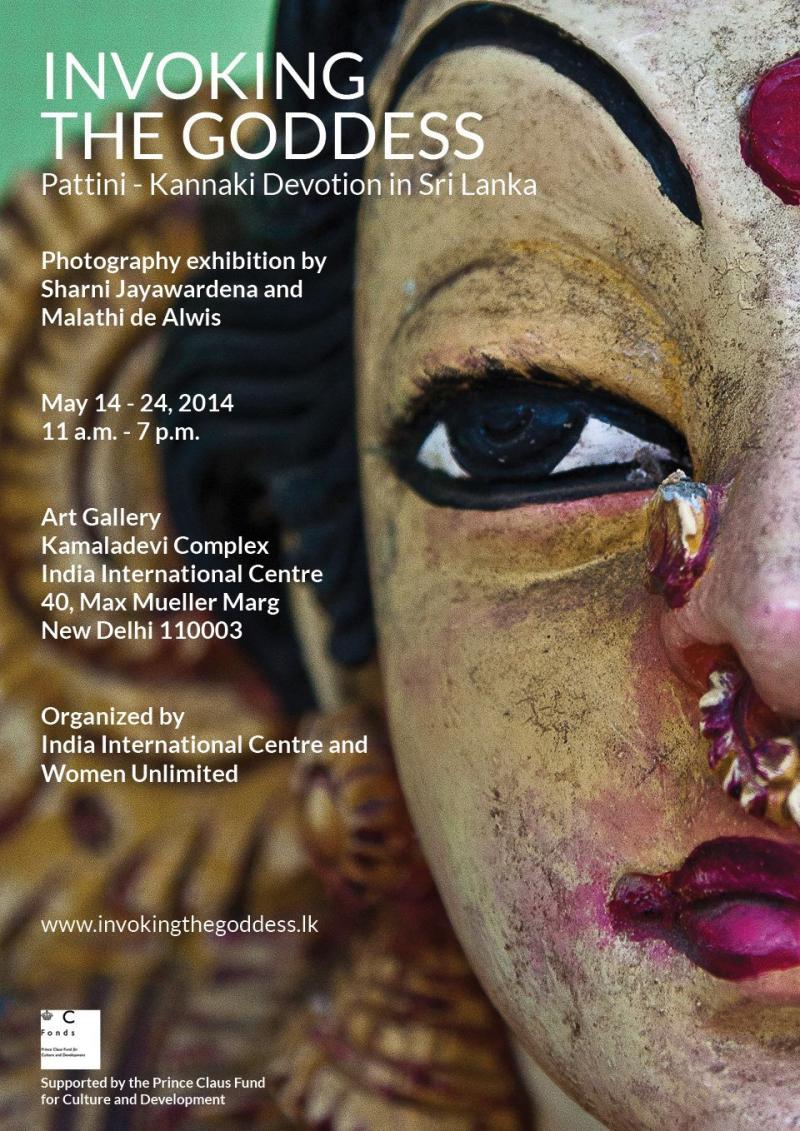

**Poster for exhibition associated with the website posted in comments section of website. Exhibits also held in various spots in Sri Lanka.: