A Radical Activist in Ceylon Politics

by Sachi Sri Kantha, May 25, 2025

Introduction

Previously, I had studied the electoral performance of three prominent Sri Lankan Tamil politicians, namely Ganapathipillai Gangesar Ponnambalam (1901-1977), Appapillai Amirthalingam (1927-1989) and Murugesu Sivasithamparam (1024-2002). All three were electorally successful in most of their attempts, though suffering defeats intermittently.

James Rutnam’s autograph (1981) given to Sachi

But, among the Tamil politicians, the case of James Thevathasan Rutnam (1905-1988) was different. He made six attempts to enter the Ceylon/Sri Lankan legislature, during pre-independent and post-independent periods, between 1931 and 1960, and lost all six times. Among the four politicians I’ve mentioned, during my twenties, I had the good fortune to be acquainted with Sivasithamparam and Rutnam for a few years, between 1977 and 1981. Rutnam’s multi-faceted career as a labor leader, businessman, a non-conventional scholar of historical studies, a journalist and an electorally un-successful politician was of special interest to me. He encouraged my English writing to the Colombo press, when I was in my 20s. He took a liking to my penchant style of analysis and introduced me to a couple of journalists in the caliber of Reggie Michael, Mervyn de Silva and complimented my pro- Tamil nationalism to S.P. Amarasingam’s Tribune weekly. This is a two-part remembrance tribute to Rutnam’s 120th birth anniversary which falls on June 13th this year. In this first part, I summarize Rutnam’s political performance.

Though glimpses of Rutnam’s career had been covered previously by Amerasinghe (1985) and Seelan Kadirgamar (2005), to the best of my knowledge, none had attempted to analyze his electoral forays to enter the country’s legislature from 1931 to 1960. Why he lost six times in the elections? What were his weaknesses? Details of Rutnam’s electoral performances, with available statistics, are given below. But I don’t have in my possession, primary source materials like specific details about Rutnam’s as well as his opponents’ electoral manifestos, news reports about their campaign meetings and electoral finance records.

Radical activism in 1920s

Born in Manipay, Jaffna, on June 13, 1905, Rutnam’s political activities as a young radical under Labour Party leader Alexander Ekanayake Goonesinha (1891-1967) during 1920s has been passingly mentioned by Kumari Jayewardana in 1971. She had noted that in 1926, along with Harry Gunawardena, D.N.W. de Silva, Valentine Perera and C. Ponnambalam, Rutnam joined the grouping, calling themselves ‘The Cosmopolitan Crew’ to organize public meeting and demonstration against Poppy Day displays by British residents in Ceylon. Poppy day’s official name was Armistice Day (Nov. 11th) that commemorated the end of First World War. Rutnam was in the forefront of anti-Poppy day celebration, because the collected funds were mostly drained off from the island to benefit the British war veterans.

S.J.K. Crwther (1888-1971), Tamil journalist from Batticaloa

This sort of activism led to Rutnam’s plunge in the First State Council election in 1931. Between 1928 and 1930, he served as the first lay principal of St. Xavier’s College (Boy’s primary and secondary school, established in 1859), Nuwara Eliya. About his pedagogy, Rutnam had reminisced in 1976, as follows:

“I introduced the compulsory study of Ceylon history, Sinhalese and Tamil. I also made physical education and gardening compulsory. I led an unsuccessful strike in Nuwara Eliya, gaining popularity nevertheless. The Daily News lashed out at me in its main editorial, calling me an “obstreperous schoolmaster who will soon have to take to his heels’. I responded rather ungallantly by calling the editor, S.J.K. Crowther a ‘cantankerous ex-padre who should go to his pulpit and learn the text. Every labourer is worthy of his hire.’ I was then twenty years old.”

In fact, Samuel James Kirubaratnam (S.J.K.) Crowther, was a Christian Tamil – like Rutnam himself – from Batticaloa, with ancestral roots in Point Pedro. He did quit his editor position at the Daily News, in 1931 due to some disagreement with the owner and publisher of the paper.

Buoyed by this type of activism, Rutnam stood as a candidate for Nuwara Eliya electorate, which was one among 50 electorates designated to choose people representatives to the State Council. From 1931 to 1952, he had contested and lost five elections from Nuwara Eliya electorate.

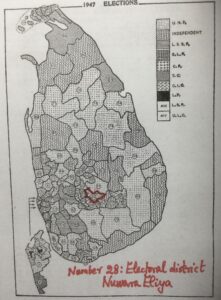

Nuwara Eliya location

The location of Nuwara Eliya can be checked in the adjacent figure. Next year, marks the 200th anniversary of ‘discovery’ of Nuwara Eliya by the British colonialists as a ‘convalescent station’ for exhausted folks in military, uncomfortable with the tropical sunny weather. Sir Emerson Tennent’s 1859 description of ‘Neuera-ellia’ was as follows: “The first visit of Europeans to this lofty plateau was made by some English officers, who, in 1826, penetrated so far in pursuit of elephants. Struck with its freshness and beauty, they reported their discovery to the Governor, and Sir Edward Barnes, alive to its importance as a sanitary retreat for the troops, took possession of it instantly, and commenced the building of barracks, and of a bungalow for his own accommodation. He directed the formation of a road; and within two years Neuera-ellia was opened (in 1829) as a convalescent station. In the estimation of the European and the invalid it is the Elysium of Ceylon.”

In the previous page to the above description, Tennent had noted the following about the ethnic-mix of Nuwara Eliya region in the first half of 19th century. “The lowland Singhalese have a horror of the cold in these elevated situations, and still more of the rain, to avoid the spattering of which on their skins they would at any time crouch under water in a stream or a tank. It is difficult to tempt them to the hills, and even the Malabar coolies shrink with apprehension from the chills of Neuera-ellia. To provide labour for these mountain roads the Government retain in their pay a body of Caffres as pioneers, the remnant of a force which was originally incorporated by the Portuguese, who introduced them from their African settlements at Mozambique. The Dutch succeeded in keeping up its strength by an immigration from the Cape, and the British maintained it by purchasing slaves from Portuguese at Goa.”

E.W. Abeyegunasekera – Rutnam’s formidable rival in 1931 and 1936

First attempt: First State Council election June 15, 1931

Rutnam had just turned 26, and a candidate representing the Labour Party. His opponent was Edwin Wilfred Abeyegunasekara representing the Liberal Party. There was another independent candidate. Nominations were called on May 4, 1931. Rutnam lost by a vote margin of 3,136 votes.

Total electorate 18,837 (Men 13,398 and Women 5,439). Total votes polled 12,572 (66.8%)

E.W. Abeyegunasekara 6,942 votes

J.T. Rutnam 3,806 votes

L.W.F. de Saram (Independent) 1,824 votes

In Rutnam’s reminiscence, “[I] was beaten, but not disgraced. I repeated my election bids on several other occasions as an independent candidate, and was defeated in every election. Once I was beaten by a small margin of votes, and I won the election petition that followed. My career would no doubt have been different had I been elected.” Rutnam’s formidable rival Abeygunasekara’s profile was ‘a resident of Hanguranketa and formerly in the Police Department. A Kandyan Sinhalese’. Please note the disproportionate balance of voters between men and women. It seems, many women were NOT registered for voting.

Second attempt: Second State Council election March 7, 1936

Rutnam was 30. Nominations were called for this election on January 15, 1936. E.W. Abeygunasekara retained the constituency, by an increased vote margin of 6,121. This time, there were four candidates, among whom one was an Indian-origin Tamil. This resulted in Rutnam being pushed to third place.

Total Electorate 38,772 (Men 23,661 and Women 15, 111); Total votes polled 19,722 (51.2%)

E.W. Abeyegunasekara 11,248

Ramaiah 5,127

J.T. Rutnam 2,663

T.B. Ilangatilaka 553

By polling 13.5% of the votes, Rutnam could safe his deposit of (then) Rs 1,000. This pattern would repeat in his next three election attempts, from Nuwara Eliya. In the presence of another Tamil-speaking candidate (Ramaiah, here) in the electorate, he would be pushed downwards. In the absence of another Tamil-speaking candidate, Rutnam would place 2nd. The predicament of competing in an election held in a multi-ethnic, multi-religious under-developed country like Ceylon with a high percentage of illiterate voters is worth a look. The following unsigned report in one lengthy paragraph appeared in the reputed British science journal Nature in 1936. For its pungency, I reproduce the report in full below. It offers a few clues to Rutnam’s losses.

“The results and still more the methods of electioneering, in the recent general election for seats on the State Council of Ceylon, afford an instructive, if somewhat alarming, example of the effects of the break in tradition, which comes with the wholesale application of the machinery of Western democracy to an Eastern society, in which the exercise of individual judgment has had neither training nor opportunity to function independently of the social or religious communal group. Everywhere religion and caste dictated the decision of the electors. Group clashes were frequent, and twelve persons lost their lives. In at least two instances, it is stated by the Colombo correspondent of The Times in the issue of March 24, Christian members of long standing and conspicuous public service lost their seats to opponents, unknown before the contest, whose principal qualification appears to have been that they were Buddhists. This exploitation of sectional prejudice was, perhaps, no more than might have been anticipated, even though it scarcely appeared in the elections of four years ago. The grant of adult franchise to both sexes has placed on the electoral register 2,500,000 voters, of whom, it is estimated, 2,000,000 are illiterate. In consequence, the voting had to be conducted by the allocation of a colour to each candidate, the ballot paper being deposited in the appropriately coloured box in blank. Yellow, the Buddhist colour, swept the board. Of forty-three contested seats, thirty three went to Buddhists, an increase from twenty eight in the previous Council. Universal suffrage was granted to Ceylon on the report of the Donoughmore Commission, which visited the island in 1927; but the results of the present election have raised in an acute form the question whether it is likely to prove as beneficial as was anticipated.”

Akin to 1931, the disproportionate balance between Men and Women voters prevailed in 1936 as well. Though given the rights to vote in 1931, it seems women were not educated to exercise their legitimate rights then.

Third attempt: By-election of Oct 16, 1943 to Nuwara Eliya electorate

M. Dingiri Banda in 1947

This by-election resulted due to the resignation of E.W. Abeyegunasekara’s resignation in June 1943. Two months previously, the Bribery Commissioner had found in his investigation, Abeyegunasekara had accepted bribes in the exercise of duty as a member of the Home Affairs Committee.

Rutnam was 38. His major opponent M. Dingiri Banda (1914-1974) was only 29. There were two more Sinhalese candidates. Rutnam was placed 2nd. The results were as follows;

Total electorate 38,772; Total votes polled 25,511 (65.8%)

M.D. Banda 12,652 votes

J.T. Rutnam 11,093 votes

T.B. Beddewela 1,484 votes

K.B. Alawatugoda 203 votes

Rutnam had lost to Banda by a vote margin of 1,559. Colonel John Kotelawala (later to be the third prime minister of Ceylon) had campaigned for the winner Banda. The Times of Ceylon newspaper columnist (writing under the pen name ‘The Whip’), was effusive in his praise to the victor in the election and his prominent campaigner Col. Kotelawala, on Oct 22, 1943, while needling the loser Jim. Excerpts:

“It was a creditable victory for Banda, But Jim [Rutnam] is undaunted by his third failure. He has promised to be back in the arena once again. In Nuwara Eliya, Nanu Oya and Ragalla, Jim polled more than his victorious rival who was not without Indian labour support…”

Four days later, Rutnam responded to this sort of rub, with sarcastic humor, and thanking his far-sighted Sinhalese voters, in the Times of Ceylon (Oct 26, 1943). Excerpts:

“…The spirit in which a defeat is taken depends on the spirit in which a contest is fought. My supporters were waylaid at carefully prepared placed, assaulted and driven back to their homes. ‘The Whip’ want me to remain dumb in the face of all this organized intimidation… The gallant Colonel [Kotelawala] came to Nuwara Eliya and raising communal cry by piping the clarion call to the Sinhalese to vote for the Sinhalese candidate. I take my hat off to those far-sighted Sinhalese voters, especially those who reside in Nuwara Eliya, who refused to follow his lead.

The Whip who was not an eye-witness to this election, has in his enthusiasm drawn a moving picture of the aged and the sick of Walapone and Udahewaheta going to polling booths and not to infirmaries. Well, if he was present, he would have been not only the aged and the infirm, but also the dead and the dying going to cast their votes!”

Rutnam was not the one to accept the results in its face value. He filed an election petition against the winner, on the grounds of voter intimidation and thuggery. British Justice Hector Horace Hearne (1892-1962), who was serving as the puisne judge then, ruled the case in favor of plaintiff. Thus, Banda was unseated on the grounds of hooliganism and election-related violence. But, for some reason, Rutnam did not contest the 2nd by-election for Nuwara Eliya electorate, held on July 22, 1944.

Fourth attempt: First Parliamentary election Sept 16, 1947

S. Thondaman in 1947

Rutnam was 42. This time, Rutnam’s major opponent Saumiyamurthy Thondaman (1913-1999) was 34. For the first time, Rutnam’s major rival was a Tamil speaker! As is well known, Thondaman (born in Tamil Nadu) was the son of head kankani of tea estate, who had accumulated wealth and influence among Indian Tamil voters, in 1920s and 1930s. In 1943, he had become the President of the Ceylon Indian Congress (CIC) as well.

In his autobiographical memoirs (1994), Thondaman Snr. only included the results of this election, without elaborating the issues raised in the propaganda meetings. To quote,

“I was elected as Member for the Nuwara Eliya seat. The voting took place on September 16, 1947. The total number on the register was 24,368, and 14,674, that is 70.7%, had voted. I polled 9,386 and Mr. James T. Rutnam (Independent) received 3,251 votes. Mr. Lorenz Perera of the Bolshevik Leninist Party forfeited his deposit having secured only 1,124 votes.” While Thondaman had received 64% of the votes polled, Rutnam could manage only 22%.

And what happened to M.D. Banda, who defeated Rutnam in the 1943 by-election for Nuwara Eliya, and was subsequently un-seated in the election petition filed by Rutnam? The 1947 Parliamentary election data book provides the following details: “Mr. Banda would normally have been disqualified from contesting a seat in Parliament this time owing to the findings of the Election Judge but a pardon given him under the Ceylon (Constitution) Order in Council has removed the bar to his entry into the legislature.” Banda contested the Maturata constituency in 1947, and won by a vote margin of 8,886, against his rival Tamil candidate S. Somasunderam (Independent). In May 1948, he would be appointed Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Labour and Social Services, and would raise to become a ranking member of UNP party in 1950s and 1960s and a Cabinet minister, only to lose once in the 1970 General election.

Ceylon – electoral map 1947, showing Nuwara Eliya location

Fifth attempt: Second Parliamentary election May 1952

Rutnam was 46. This time, due to the Indian and Pakistani (Residents) Citizenship Act that became law on August 5, 1949, the strength of Indian Tamil voters were drastically reduced in constituencies where they were in majority. Nuwara Eliya electorate was one of the worst affected, along with Talawakelle, Kotagala, Nawalapitiya, Maskeliya, Haputale and Badulla.

Nuwara Eliya constituency had 24,295 voters in the 1947 general election. But the number of voters after the 1950 revision of the voters list amounted to only 9,279. Subsequently, after 1951 revision, the number of Tamil voters was limited to ONLY 319. This statistic is from Thondaman’s autobiography. While Thondaman wisely refrained from contesting the 1952 general election, Rutnam persisted. He was placed third among the four candidates, behind another Tamil Independent candidate (Vijayaratnasingham), by a slender margin of 7 votes. The results were:

Total electorate 9,279; Total votes polled 6,009 (64.8%)

P.P. Sumanatilaka (UNP) 3,852

V.A.Vijayaratnasingham (Independent) 849

J..T. Rutnam (Independent) 842

A.J.M. de Silva (Independent) 391.

It can be noted that, given that the total number of registered Tamil voters were only 319, vote share of both Tamil candidates (Vijayaratnasingham and Rutnam), among non-Tamil speaking voters, exceeded the total number of Tamil voters in the electorate. Lack of a recognized party affiliation became a stumbling block for Rutnam to enter the portals of parliament.

Sixth attempt: Fourth Parliamentary election March 19, 1960 –

Rutnam was 54. This time, Rutnam opted to check his luck at a Colombo constituency, and chose Colombo South (made as a two member constituency for the first time, due to major increase of Tamil speaking population in the capital). The sitting member for Colombo South in the 1956 elections had been Bernard Soysa (LSSP). Among the 10 candidates, Rutnam was placed a poor 5th, collecting only 1, 273 votes. Winners were, Edmund Samarawickrama (UNP) and Bernard Soysa (LSSP). For this election, Rutnam was allotted the symbol of ladder. Results were as follows

Total electorate 42,367; Total votes polled 60, 758 (71.7%)

Edmund Samarawickrama (UNP) 25,312

Bernard Soysa (LSSP) 16,206

Hema Dabare (SLFP) 8,851

Gamini Fernando (MEP) 5,412

J.T. Rutnam (Independent) 1,273

Bin Hassan (Independent) 1,188

M.L. Jayasekera (Independent) 794

Rasaratnam (Independent) 333

S.R. Yapa (SMP) 185

K.F.R. Fernando (Independent) 42

This time, Rutnam forfeited his deposit money, and learnt the sour lesson after five attempts that being an Independent candidate in party-oriented politics wasn’t worth the trouble to have the MP tag behind his name. Now in hindsight, one can note that three of his opponents (namely M.D. Banda, S. Thondaman and Bernard Soysa) subsequently turned to be influential Cabinet ministers. I did ask Rutnam, why he left his mentor Goonesinha in 1930s. To this query, his answer was, “You see. He prostituted his lofty principles for success in political pole-jumping (a word-play by him, referring to ‘poll-jumping’ as well) contests. Eventually, even Sinhalese voters soured on him in 1950s.” This comment relates to Goonesinha targeting and taunting the Malayalee (Keralite laborers) ethnics residing in Colombo, in early 1930s, to gain an upper hand in rivalry with the upcoming Leftist politicians, who were encroaching Goonesinha’s political turf.

To match the record of Rutnam’s six losses in elections, there was another Tamil politician Chinnaiah Arulampalam (1909-1997) from Jaffna. His record was six losses and one win, between 1952 and 1977. He contested Kopay constituency in 1952 and 1956; and then the newly demarcated Nallur constituency in 1960 (March and July), 1965, 1970 and 1977. Only in 1970, Arulampalam won against the Federal Party heavy weight Dr. E.M.V. Naganathan with a small vote margin of 608 votes, after losing to him consecutively for three times. Arulampalam also lost to C. Vanniasingham twice in 1952 and 1956, and to M. Sivasithamparam in 1977.

Conclusion

In 1988, the year of Rutnam’s death, Dr. Stanford Friedman delivered a presidential address of the American Psychosomatic Society, in which he focused his attention on the ‘marginal man personality concept’ of sociologist Everett Stonequist. In my overall inference of Rutnam’s political career, this fits well with his experiences. Who is a marginal man? As cited by Friedman, a marginal man is ‘the individual who through migration, education, marriage or some other influence leaves one social group or culture without making a satisfactory adjustment to another finds himself on the margin of each but a member of neither.’

After being born at Jaffna into a Christianized Tamil family with means in 1905, then with schooling in Colombo and engaging in agitational politics as a young radical in Colombo during 1920s, Rutnam got married to a Sinhalese lady Evelyn Wijayaratna (1912-1964) in 1932, against parental opposition. He contested the Nuwara Eliya constituency repeatedly from 1931 to 1952 for five times, and morphed into a ‘marginal man’. I don’t think, he was fluent in colloquial Sinhalese language. But, from my experience in conversations, his Tamil wasn’t good either. His spoken Tamil was that of 6-10 year old child’s babbling grade! But, he was an accomplished speaker in English. With such superlative English skills, Rutnam simply couldn’t attract the illiterate Sinhala – Indian Tamil plantation workers. This became the primary reason for all his six electoral defeats.

Like a few best actors being miscast for some of their movie roles, Rutnam (one of the best politicians of his generation, with a commanding presence of facts and talent) was a miscast in the Nuwara Eliya constituency, he had tried his fortune. To my query, he told that, contesting as an Independent (other than he first attempt in 1931) hurt his chances, after party politics came to be prominent since 1947.

Rutnam died on Nov 4, 1988, at the age of 83. He had been a widower since 1964, following the death of his wife Evelyn Wijayarathna (a Sinhalese, 1912 – 1964) at a relatively young age of 52. They had been married for 32 years. I close this appreciation to Rutnam’s political career quoting the words of Stonequist. ‘The marginal man is the key personality in the contacts of cultures. It is in his mind that the cultures come together, conflict and eventually work out some kind of mutual adjustment and interpretation. He is the crucible of cultural fusion.’ Rutnam was like a tight-rope walker in politics who was always toppled by voters; specific choice of Nuwara Eliya constituency, bad luck, lack of oratorical skills in vernacular tongues and lack of party affiliation hindered his winning chances. The reputation he missed in politics, Rutnam gained through his ardent pursuit of archeological research and history studies. His gracious heart to help the journalists and researchers was a treasure for those who were lucky to be in contact with him.

REFERENCES

Amarasingam S.P: Evelyn Rutnam 1912-1964. Tribune (Colombo), Sept 19, 1964, 10(42): 12.

Amerasinghe A.R.B.: James Thevathasan Rutnam. In: James Thevathasan Rutnam Festschrift 1985, edited by A.R.B. Amerasinghe and S.J. Sumanasekara Banda, UNESCO National Commission, Sri Lanka, Colombo, 1985(?), pp. 2-13.

Anon. News and Views – Electioneering in Ceylon. Nature, Apr 4, 1936; 137: 570.

Ceylon Daily News. The State Council of Ceylon, 1936, Associated Newspapers of Ceylon, Colombo, 1936, p.41.

Friedman SB. The concept of ‘marginality’ applied to psychosomatic medicine. Psychosomatic Medicine, 1988; 50 447-453.

Kadirgamar Seelan: James Thevathasan Rutnam. Extended version of the Centenary Memorial Meeting Speech, Colombo, Dec 2, 2005; updated on Feb 15, 2013.

https://silankadirgamar.blogspot.com/2013/02/james-thevathasan-rutnam-centenarary.html (accessed May 4, 2025)

Jayawardena, Kumari: The origins of the Left movement in Sri Lanka. Modern Ceylon Studies, July 1971; 2(2): 195-221.

S.L.: Politician par excellence – M.D. Banda. Sunday Observer, Colombo, Mar 16, 2003.

Rutnam, James T: Some memories and reflections. Tribune (Colombo), June 12, 1976, pp. 15-18.

Rutnam, James T: Nuwara-Eliya bye election – Defeated candidate’s account of contest. Times of Ceylon (Colombo), Oct 26, 1943.

Selvarajah, N (compiler): A Select Bibliography of Dr James T. Rutnam, Evelyn Rutnam Institute for Intercultural Studies, Jaffna, 1988, 37 pp.

Sri Kantha S: Voter Preference on Amirthalingam at the General Elections, 1952-1989. In: Varalaatrin Manithan – Saga of Late Leader – A. Amirthalingam, edited by S. Mahalingam and Panch Ramalingam, Amirthalingam Memorial Foundation, Surrey, UK, 2002, pp. 201-206.

Sri Kantha S: M. Sivasithamparam – Little memories about a Big Man. Ilankai Tamil Sangam (USA). New York website. June 18, 2002..

https://www.sangam.org/ANALYSIS/Sachi06_18_02.html (accessed May 5, 2025).

Sri Kantha S: G.G. Ponnambalam (1902-1977); His power and plight as a Tamil leader. Illankai Tamil Sangam (USA), New York website, May 8, 2020.

https://sangam.org/g-g-ponnambalam-1902-1977-his-power-and-plight-as-a-tamil-leader/ (accessed May 5, 2025)

Tennent, James Emerson: Ceylon – An Account of the Island Physical, Historical and Topographical, vol. 2, Longman, Green, Longman and Roberts, London, 1859, pp. 259-264.

Thondaman S: Tea and Politics – An Autobiography, vol. 2: My Life and Times, Navrang and Vijitha Yapa bookshop, Colombo, 1994, pp. 39 and 77.

Error correction:

1. M. Sivasithamparam’s life span is from 1924 to 2002. Not, 1024-2002.

2. Friedman’s reference should be as follows:

Friedman SB. The concept of ‘marginality’ applied to psychosomatic medicine. Psychosomatic Medicine, 1988; 50: 447-453.

In the 2nd part of this essay, that will’s follow, I’ll provide my interactions with James T. Rutnam, between 1977 and 1981.