The death of a Tiger and the fate of a nation

by Ben Hiller, ‘Red Flag,’ Australia, July 5, 2018

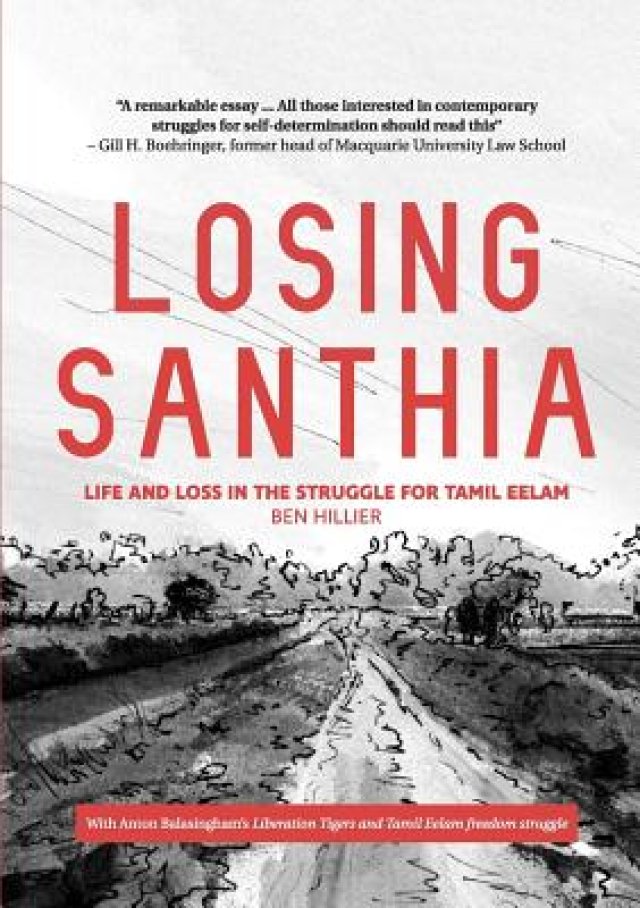

Sponsored by the Tamil Refugee Council, Red Flag editor Ben Hillier travelled to Sri Lanka and Indonesia in November to piece together her story. Santhia’s life was extraordinary yet common; her fate bound to the decades-long national liberation struggle of the Tamils.

This is part one in a continuing series. Part two can be found here.

Half a dozen young men, ex-cadres dedicated to national defence, sit on plastic chairs beneath the seven-storey Marian Shrine of Graha Maria Annai Velangkanni (Our Lady of Good Health), an imposing Indo-Mughal-styled Catholic temple in Medan, northern Sumatra.

In turn, each bares his wounds. A foot, mangled bones almost protruding through the skin; welts in a forearm and a chest, right near the heart, where bullets tore through; an eye white blind. Shrapnel remains embedded in their bodies almost a decade after the conflict’s terrible end.

They once were soldiers of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). Several fought against the final Sri Lankan military offensives in their homeland. But there are no war stories today.

“Our life is finished.”

Only one can speak English, but he relays their sentiments. “We are hoping for our children’s future. We have no country … but we are human and we’d like to be living like a human. We suffered in Sri Lanka. Now we suffer in Indonesia.”

These Tamils fled, only to be marooned on the western edge of this vast archipelago – their injuries never properly treated; their situation an open sore.

Several hundred are here, in Indonesia’s fourth largest city. Perhaps 100-150 have been granted refugee status, yet all remain in limbo. Indonesia is not a signatory to the United Nations refugee convention. While UN-approved people are released from detention, they have few rights and are restricted in their movements.

“We can’t go out at night. We can’t go to the beach-side. We can’t work. We can’t drive the car. We are under the control of immigration”, they say.

“Still we hope the UNHCR [the UN refugee agency] or other countries will help us, because we can’t go back to Sri Lanka. The problem is the government … We have been living out of the country for seven years, nine years. [If] we go there, what can we do? The government won’t give us a chance to live … We can’t go back.”

Across Tamil Eelam in the north and east of Sri Lanka, in south and south-east Asian refugee camps and communities and in the diaspora, Tamil activists are in political disarray. Hundreds of thousands are stateless or permanent émigrés. Millions lack national rights.

The routing of the Tigers has disorganised and demoralised a nation, the majority of whom previously were cohered around a liberation struggle.

“Those who fought for the movement are suffering the most [under] local authorities, despite having contributed something for people’s liberation”, a destitute former LTTE cadre says over Skype from another south-east Asian country.

“There are people here who lost their families in the war and are now fighting for their lives because of their injuries. We’re all living in fear. We can’t even go to the local shop because there is a crackdown here. We are stateless. I haven’t seen my husband in a decade; our child doesn’t know his father. That is the situation for many families.”

The LTTE was one of the most powerful national liberation insurgencies of the post-World War Two era. From guerrilla origins in the early 1970s, the organisation, by the final decade of the 20th century, established a de facto state in the north of the island, repelling and expelling the Sri Lankan military, police and security forces. It was a bulwark against state-sponsored colonisation schemes for Sinhalese Buddhists, the majority ethnic group from the south and centre of the island.

But the end, when it came in 2009, was devastating. Almost all the leadership and many or most of the leading cadres, along with tens of thousands of civilians, were wiped out. Of those surviving, tens of thousands fled the country.

Nearly a decade later, the casualties continue to mount. Santhia was 42 when her kidneys failed. She succumbed on 1 October last year in a Jakarta hospital, having been stranded in Indonesia for more than seven years. Despite being acknowledged as a refugee, she could not secure resettlement in another country.

Like her brother and many teenagers who resisted Sinhalese-state oppression, Santhia joined the Tigers young. She rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

“Santhia was in charge of Black Tigers administration and logistics and the Imran Pandian women’s brigade administration and logistics”, a former comrade says. “She was in the 18th batch of the women’s wing, which would have been [inducted] in 1992 or 1993.”

The Black Tigers was an elite commando unit, its membership secretive even within the ranks of the LTTE. In the Imran Pandian division, she reported to Gaddafi (an assumed name), former bodyguard of Tiger supremo Velupillai Prabhakaran.

In the mid-2000s, Santhia married Kumaran, a senior military commander and nephew of brigadier Balraj, one of the highest ranking LTTE leaders. She moved to Kilinochchi town, the administrative capital of the Tamil state, in the northern Vanni – the mainland area below the Jaffna peninsula, stretching from Mannar on the west coast to Mullaitivu district in the east and south to Vuvuniya.

When, in 2006, the fourth Eelam war erupted (the previous wars are generally dated 1983-87, 1990-95 and 1995-2002) after peace negotiations broke down, the Sri Lankan government, led by Mahinda Rajapaksa, vowed to liquidate the resistance. All hell was unleashed in the north.

Kumaran and Santhia’s brother disappeared in the 2009 final assaults on Mullaitivu, the military stronghold of the LTTE. On a small stretch of beach at Mullivaikal village, thousands were killed. Here, there are still remnants of bunkers dug desperately with bare hands as bombs cratered the landscape.

(One way of picturing the operation: imagine the Australian army sweeping across the north of Tasmania, displacing the population in its advance before raining death on a population of several hundred thousand corralled at Binalong Bay.)

Santhia survived the war and later internment and fled with her young son across the Palk Strait to Tamil Nadu, in southern India, before trying to reach Australia. They and about 100 others, including 15 children, spent 60 days at sea in the northern Indian Ocean. It was late 2010.

Several men here in Medan were on the same boat. “She didn’t know if her husband was living or dead. She was thinking about this the whole time”, one of them says. “She left India mainly because she wanted to save her son.”

Diesel and supplies ran out 15 days after they launched. The next 45 days were spent drifting, fishing and collecting rainwater. They traded money and jewellery with some fishermen. Then the GPS failed, leaving the vessel directionless, they say. Eventually, the asylum seekers landed on a deserted island in western Indonesia.

The navy picked them up a week later and placed them in immigration detention, with families housed in a free camp near Jakarta. Santhia was later granted refugee status and transferred to the Medan immigration centre.

“In 2014 the UNHCR [initiated] the resettlement process to America”, a friend says. “She finished the American Embassy interview and finished the medical [evaluation], too. Then, the IOM [International Organization for Migration] brought [her back] to Jakarta. She hoped she could go to America … But she was rejected.”

Midday hymns from an upstairs choir echo around the forecourt in which we sit. The men volunteer here. Helped by pastor James Bharataputra, who is also Tamil and the man behind the grand design of the Graha Maria Annai Velangkanni, they are building a school for Tamil children in a nearby building owned by the parish.

The youngsters have decorated the plywood walls with crayon – mountains, oceans and beaches, waterfalls and flowers. The resources are few; this is just getting off the ground. One adult volunteer is finishing off the touches of a Mickey Mouse painting at the entrance.

In a back room of the church the following day, Santhia’s cousin sits quietly. “Santhia was very kind and very clever. She was a talented poet”, she says. “She was very angry … And she saw the military kill Tamil people. That’s why she wanted to join the LTTE.”