by Sachi Sri Kantha, October 12, 2025

Front Note by Sachi

In 2010, I wrote a humorous verse ‘Six Blind Women of Gringo Land who went to see the Tiger’ [https://sangam.org/2010/03/Blind_Women.php?uid=3867], about the six American journalist who covered the Eelam war. It was inspired by John Godfrey Saxe’s poem. Subsequently, I also wrote an appreciation to the only American woman academic ,Prof Margaret Trawick (1948 – 2022) [https://sangam.org/memoriam-professor-margaret-trawick-1948-2022/], who learnt Tamil and covered the Eelam war from the angle of Tamil side. Another notable companion, in the mold of Prof. Trawick is Prof. Dagmar Hellmann-Rajanayagam (b. 1931), from Germany.

Eelam Tamils were blessed to have scholars like Dagmar Hellmann-Rajanayagam, who is chronologically senior to Margaret Trawick. While some confused ‘human rights flag waving’ Sri LankanTamil women academics (likes of Radhika Coomaraswamy, Rajasingham sisters – Nirmala, Rajani and Sumathy, Rajeswary Balasubramaniam) were foul mouthing the LTTE’s women warriors for their self-serving purposes, non-Tamil academics like Trawick and Hellmann-Rajanayagam viewed LTTE women from a distinct perspective. Among the many academic articles contributed by Hellmann-Rajanayagam, I selected her 2008 paper here, for a singular reason to rebut the bias of Dr. Sharika Thiranagama (daughter of Rajani Thiranagama, born in 1980) on the ideals of LTTE warriors, expressed recently in a September 2025 ‘Jaffna Monitor’ interview. [https://www.jaffnamonitor.com/featured/jvp-still-denies-the-tamil-ethnic-question-sharika-thiranagama-speaks-to-jaffna-monitor/].

Dagmar Hellmann-Rajanayagam

There are numerous plus points in this study of Dagmar Hellmann-Rajanayagam. First, she highlighted the military activism of leading LTTE women; including that of 2nd Lieutenant Malathi (aka Sakayasili Pedrupillai, 1967-1987; a Catholic from Mannar), Col. Thamilini (aka Subramaniam Sivakamy, 1972-2015), Lieutenant Col Bhavaniti and Major Kecari. Secondly, she had rebutted the claim promoted by Prof. Neloufer de Mel that ‘rape was the only reason for women to join LTTE’, by inferring that this is an oversimplification.

Thirdly, in opposition to the views currently promoted by Dr, Sharika Thiranagama and her coterie of women academics that LTTE warriors were brain-washed to die for Prabhakaran’s ideals, Prof. Dagmar Hellmann-Rajanayagam asserted “Tamil women join the Tigers not to die, but to fight. Death is taken into account, but is not necessarily anticipated. This is a decisive difference to the situation of Muslim women [fighters].” Fourthly, Prof Hellmann-Rajanayagam also separated the ideals of LTTE from the Islamic militant movements in Mid East, in generating the specific armory derisively tagged as ‘suicide bombers’ by the Western analysts of warfare. Fifthly, Prof Hellmann-Rajanayagam also rebutted the logic of human rights barkers and influential feminists from Sri Lanka (such as Radhika Coomaraswamy and Neloufur de Mel) that the LTTE was a sham movement to advance women’s rights. Sixthly, Dagmar also exposed the cultural ignorance of dumb journalists such as Jonathan Hillel Kay from Canada, who falsely claimed in 2002 that “Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat has copied the Tigers’ strategy of using the mass media’ in an opinionated column about the strategy of using female suicide bombers!

Naysum Saravanamuttu 1897-1941

On the minus side of this study, I may add that Dagmar Hellmann-Rajanayagam, in her review of pre-LTTE political activism among Tamil women, inadvertently overlooked the electoral record of the first Tamil woman from Jaffna, Mrs Naysum Saravanamuttu (1897-1941), who won elections in Colombo during 1930s. Naysum was elected to the First State Council in a by-election held on May 30, 1932, from Colombo North constituency, following the unseating of her husband, the popular physician Dr. Ratnajothi Saravanamuttu due to ‘statutory disqualification’. Naysum Saravanamuttu achieved this distinction at the age of 35 years. She had to face another by-election on Nov 12, 1932. This also, she won. Subsequently, in the 1936 general election for State Council, Naysum won for the third time. Quite an unblemished record for a Tamil woman, to win consecutively three times in Colombo. Women were allowed to vote in Ceylon, only in 1931! Naysum died on Jan 19, 1941, at a young age of 41. Dagmar is indeed correct in her Note 5, that between 1942 and 1980, no Tamil woman was a member of Parliament.

It should also be noted the meager details presented by Dagmar about Lakshmi Saghal nee Swaminathan (1914-2012) identified as ‘a Tamil doctor from Malaya’ is misleading. In reality, Lakshmi was of Kerala origin, though her father Swaminathan practised law at Madras High Court. Lakshmi also practised as a gynecologist in Chennai following her medical degree, and went to Singapore only in 1940; there only she was recruited into Indian National Army, after her meeting with Subhash Chandra Bose.

A reformatted version (prepared by Sachi Sri Kantha in 2025), of this vital contribution to Eelam Tamil studies by Dagmar Hellmann-Rajanayagam in 2008, is presented below.

The paper also carries 21 ‘Notes’, indicated in the text by superscript numbers. These notes are reproduced at the end of the main text, and are valuable additions in rebutting the half-baked anti-LTTE views, expressed by other women scholars. For their relevance and vitality in checking valid facts, do not ignore reading Notes 11, 13, 19, 20 and 21. These Notes are followed by ‘References’ in alphabetical order. These references are also reproduced faithfully. The subtitles, spellings of names and places, and words in italics are retained as in the original. Four Figures and five photos incorporated in the original version have been eliminated. Instead, I include three photos of LTTE celebrated women. Inadvertent type-setting error(s) have been silently corrected.

I submit this to the memories of 2nd Lieut Malathy, aka Sakayacili Pedropillai (1967-1987), whose 38th anniversary of death is marked on October 10th, and that of Col. Thamilini, aka Subramaniam Sivakamy (1972-2015), whose death occurred on Oct 18, 2015.

Female Warriors, Martyrs and Suicide Attackers’ Women in the LTTE*

Dagmar Hellmann-Rajanayagam

Universitat Passaw

[International Review of Modern Sociology, spring 2008; 34(1): 1-25]

Abstract

In this article, I undertake two things. First, I present an overview of the concept of women’s nature and roles in traditional and contemporary Tamil society in Sri Lanka. Second, I introduce the LTTE, its history, programme, ideas and way of governing in the areas under its control with a particular emphasis on developments since 2002. In this context, I analyze the LTTE’s concept of women and female warriors, followed by some case descriptions.

Introduction

On 28th November 2007 a Tamil woman handicapped by polio gained access to the vicinity of a minister in the cabinet of Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapakse and Leader of the EPDP (Eelam People’s Democratic Party), Douglas Devananda and detonated a bomb she had reportedly hidden in her bra (www.iht2007, www.spiegel.de). While she and some of her bodyguards died, the minister remained unharmed. This incident was the last in a long list of suicide attacks performed by female members of the LTTE, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. Before that, on 25th April 2006, another woman pretending to be pregnant had blown herself up near Lt. Gen. Sarath Fonseka who was severely injured in the attack (www.bbc.co.uk).

Female suicide bombers have become notorious in several Islamic movements. Women in the LTTE came on the scene earlier (though they were not the first female suicide attackers), and have made their mark equally. The young woman who allegedly assassinated Rajiv Gandhi on 21st May 1991, Dhanu, is the most famous among them. The phenomenon of women suicide bombers has led several authors to lump all movements together and attribute the same or similar motives to all of them (Skaine, 2006; Bloom, 2005; Chenoy, 2002, 2004).1 This, however, is a misperception. For one thing, female fighters or female warriors are nothing new in various libration movements the world over, at least in modern times, e.g. in Latin America, in the Spanish Civil War, the Communist movement, the Italian Red Brigades in Italy and the Red Army Faction in Germany, and not least Laila Khaled, the PFLP (People’s Front for the Liberation of Palestine) member, who became famous in the 1970s. What is astonishing is that again in modern times this fact should have attracted attention as something out of the ordinary, something not fit for women. Women, as Sandra Whitworth (2006) and others have pointed out, are considered as opposite of fighters and warriors by nature, a species or group that need special persuastion or inducement to become violent (Coomaraswamy, 2002). Chenoy (2002), Mukta (2004) and de Mel (2001) among others, have argued that this is not the case. Especially in the Indian context, examples of fighting women and warrior goddesses abound (e.g., the Rani of Jhansi or Amba of the Mahabharata, or, nearer to our time, the women of the Indian National Army (Gopinath and Shivadas, 2007; Ward Fay, 1991). The phenomenon of female suicide attackers, however, is more recent.

In this article, I shall undertake two things. First I will outline the concept of women’s nature and roles in traditional and contemporary Tamil society in Sri Lanka. Since I have done this in detail in earlier pieces, I shall keep this short. Second, I shall introduce the LTTE, its history, programme, ideas and way of governing in the areas under its control and mainly outline related developments since 2002, as prior developments have been more extensively documented in Hellmann-Rajanayagam (1994). In this context, I will emphasize the LTTE’s concept of women and female warriors in greater detail, followed by some case descriptions.

The Concept of Woman in Tamil Society

Women in Tamil society in general have a respected but simultaneously ambivalent and somewhat restricted status. Early Tamil classical literature knows educated women in the shape of poetesses like Auvaiyar of the Purananuru and in later centuries devadasis (temple dancers) like Madhavi of Cilappatikaram fame (1978). Queens are mentioned in the literature and in inscriptions by name as socially and economically powerful in their own right. The Tirukkural mentions the wife as the helpmate of her husband and on a more or less equal footing with him. Epics and folk tales from the later pre-colonial centuries, however, portray women as ideally weak, chaste, shut up in the home and ignorant about the outside world, and shy (Beck, 1982).2 In these tales, however, women have or acquire special powers as women, especially as married women and are labelled as the saviouresses of their menfolk (Viswanathan-Peterson, 1998). Folk wisdom and proverbs particularly in Northern Sri Lanka forbade education for women, and corporeal punishment of wives (though never of the honoured mother, who was a temple) was considered an honourable act (Hellmann-Rajanayagam, 2007a).3

Mother Pupati Kanapathipillai in ‘Fast unto Death’ 1988

In any case, like in many traditional societies, women could gain social standing primarily as wives and mothers of sons, even though the famed poetesses were thought to have been unmarried. In spite of this very restrictive attitude education of women and girls was introduced in Jaffna quite early: with the foundation of the first girls’ school in Vattukottai by the American Mission in 1823. This school became extremely successful in a short time, because even traditional Jaffna recognized the value of education for women. The most well-known religious reformer4 of Jaffna, Arumuka Navalar (Hellman-Rajanayagam, 1989), argued for the education of girls already in the 1850s, because, he said, only then would they become good wives and mothers and would be able to conduct the affairs of their husbands in an emergency (Hellmann-Rajanayagam, 2007a). The Sinhalese areas traditionally granted more freedom to women, yet it took much longer for girls’ schools to get accepted there.

Whereas classical Tamil literature and mythology do know warrior goddesses like Durga, the slayer of demons and Kali, the goddess of war and of the cremation ground (to name only a few), neither heroic literature nor reality give us any hint about female fighters or warriors: men fight and women induce them to it (Purananuru; Trawick, 1999; de Mel, 2004). The goddesses are, however, not considered role models for women, they are wild and dangerous virgins; rather the married and thus tamed goddesses like Lakshmi and Parvati are emulated (Hellmann-Rajanayagam/Fleschenberg, 2008). We do not, e.g. find a figure like the Rani of Jhansi.

The LTTE-A Short Outline

Let us briefly look at the LTTE, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam or Tamil Tigers for short (Hellmann-Rajanayagam, 1994, 2007a). The movement was established in 1976 and originated out of several student wings of the respective Tamil parties in the North and Northeast of Sri Lanka. The militant movements – and there were far more than one – were dissatisfied with the slow and hesitant progress of the established parties to achieve justice and equal treatment for the Tamils in Sri Lanka. While the parent parties relied – unsuccessfully – on parliamentary methods, the youth came to believe that only militant methods would ensure that the Tamils would no longer be treated as second-class citizens in their own country as had been the case for decades after independence. If the long-standing demand for autonomy would not serve, why not ask for an independent Tamil state straight away? This had been the election demand of the Tamil coalition TULF (Tamil United Liberation Front, established in 1974) in 1977; they pursued this goal by parliamentary and non-violent means, though. In the face of the coalition’s failure, the LTTE adopted the call for independence and fought for it since 1983 in a bloody and brutal war with the Sri Lankan Armed Forces. Fortunes repeatedly changed for both sides. Suicide attacks and assassinations were means of choice for the Tigers, at least as long as they conducted a guerrilla war. In later years they fought increasingly conventional campaigns, complemented by daring attacks on military and economic targets. The Sri Lankan armed forces, in turn, employed arbitrary arrests, harsh anti-terror laws (which created the terrorists they were aimed to eradicate), rape and torture, all to no avail.

In 2002 both sides had fought each other had fought each other to a stand-still, and a ceasefire was negotiated with the help of the Norwegians. Since then the LTTE is officially in political and administrative, not only military, control of the Northern Tamil areas with the exception of the Jaffna peninsula which is under army occupation. The truce, however, held only for four years, some say even less, and since 2006, the ‘shadow war’ has, as admitted by both sides, turned into full-fledged war again. The Sri Lanka Government officially annulled the agreement on 2nd January 2007 (www.tamilnet.com 2008). A renewed offensive by the Sri Lankan Armed Forces in the North, announced since the summer of 2007, when it had purportedly regained the East, has not really got off the ground, partly because of fierce resistance by the LTTE, partly because of second thoughts by the Sinhalese. The situation has turned into the usual stale-mate, well-known since two decades.

Women in the LTTE

To what extent did the LTTE take into account or further feminist aspirations or ‘women’s concerns’? Like other militant groups among the Tamils and in Sri Lanka in general, the LTTE propagated equal rights and treatment for women from the start in its writings and propaganda statements. But it was one of the first militant groups to go beyond that and to actively call and recruit women into the movement as active members and fighters from the late 70s and early 80s onwards. The argument was that only in this way would it be possible to further and ensure women’s emancipation.

This was a radical step, and it may be compared with the situation in some Islamic countries. As stated above, women had traditionally been relegated to the domestic sphere in Tamil Sri Lanka and active female warriors were quite unknown. The TULF, while politically radical in its demands for an independent Tamil state, showed a strange restraint where women’s questions were concerned and rarely recruited women even for political work. In the early 20th century, voting rights for women had been fiercely opposed by the conservative elite of Jaffna, led by politician P. Ramanathan, and when universal suffrage was granted to Sri Lanka in 1931, this meant the end of the world as he knew it for him (Hellmann-Rajanayagam, 2007a). Very few Tamil women were active in the Ceylonese parties and the struggle for independence, whatever little there was of it (Jayawardena/Kodikara, 2002, Goonesekere, 2002).6 This did not change even when Sirima Bandaranaike became the successor of her husband after the latter’s assassination. She was more an exception than a role model.

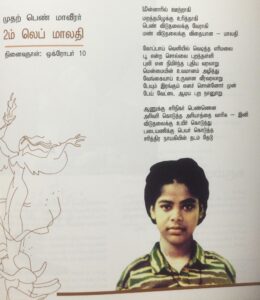

2nd Lieut. Malathy aka Sakayacili Pedropillai (1967ー1987)

The LTTE, when it gradually turned into the only militant organization that had any weight in the Tamil areas in the 90s and could spread its ideas in the North, first rather unthinkingly and naively demanded ‘emancipation of women’ without clearly spelling out what this might mean under the circumstances. It seems to have been a slogan rather than a programme that was part of the propaganda of a credible militant movement, particularly, since all other militant organisations pouted the same phrases. There was little consideration of actual social and political conditions and traditions. Demands and accusations remained generalized and insufficiently took into account the actual social situation in Jaffna. They originated from a vaguely leftist and socialist attitude, influenced to a not inconsiderable extent by corresponding developments among the Sinhalese, especially in the JVP. Here, too, ‘emancipation of women’ was part of the baggge without its contents being always clearly spelt out.

An example for the confusion would be the demand for the abolition of the ‘dowry evil’, no doubt taken from similar demands in India. The ‘dowry evil’ is certainly one such in India and has justly attracted attention and opprobrium not only from women’s organisations and movements. Dowry is interdicted by law there. The topic was unquestioningly adopted in Sri Lanka without considering the rather different situation there.7 Adele Balasingham (1993) authored besides her portrayal of female fighters in the LTTE a pamphlet entitled ‘unbroken chains’, that described the dire situation of women in Jaffna and the alleged dowry evil – without wasting a word of explanation on the original meaning and legal constitution of dowry in traditional Jaffna society (Balasingham, 1994). According to the Tecavalamai, the traditional law of Jaffna, dowry was given to daughters in lieu of inheritance, because they were not entitled to inherit. The brothers in a family were not able to marry before they had earned the dowries for all their sisters. This dowry was intended to ensure that the daughter and wife was economically secure even if the husband died or left her. It was only inheritable in the female line: from mother to daughter or granddaughter, or to the niece and grandniece. If the wife died without issue, it fell back to her mother or other female relatives (Muttukistna, 1862). The husband could manage his wife’s property only with her consent. Only in 1911 the British administration changed this by law and enabled the husband to dispose of his wife’s property without her consent (Hellmann-Rajanayagam 2007a, 1994; Thambiah, 1950). There is no doubt that after this legislation dowry really became an ‘evil’ and now considerably limits the marriage prospects of many girls in Jaffna (Canmukalinkan, 2002).

Which is why the LTTE forbade it while administering Jaffna and forbids or at least discourages it nowadays in Killinochi, on pain of severe penalities. Adele Balasingham (19998) has considerably changed her view of dowry in later publications. But even in her study ‘Will to Freedom’ she laments the fate of Tamil women who are only allowed to be wives and mothers and demarcates herself from them explicitly – simultaneously and by her own admission profiting from the help and care of precisely these wives and daughters.

The image of women in the LTTE changed only very gradually and with a growing number of female members. At the same time, demands and programmes became more specific. Nowadays it is not so much the dowry that is considered evil, but how it is demanded and used (see below). A similar change has occurred with the attitude towards rape. In the 80s, when brutal rapes of Tamil women and girls by Sinhalese soldiers were wide spread (they still are common) and feared, the LTTE condemned these incidents with the explicit argument that the violated women were not longer fit to marry Tamil men (Hellmann-Rajanayagam, 1986; de Mel, 2001).8 The alleged sexual impurity and loss of chastity were the only factors considered important, not the violation of the physical integrity of the woman. This led to severe criticism of the machismo of the LTTE. But it was only when a women’s wing of the LTTE was established that the argument of shame and impurity gradually faded into the background. Nowadays rape is still little talked about, but this is a conscious policy of the women’s organisations; rape should not be made into a political instrument as has been the case in Bosnia (Trawick, 1990).9 Women who are raped are told in consultation that this is nothing to be ashamed of, it should be considered on the level of an accident for which the woman could not be blamed (Yo. Kalaivilly, 2004). The LTTE encourages its veterans to marry women who have been raped to ensure their social standing.

Women Fighters of the LTTE

Under the conditions described the recruitment of women for combat was not really easy. Only the efforts of Lt. Col. Tilipan, a high-ranking LTTE member, bore fruit in the 80s. Tilipan (Rasiah Parthipan) was a third-year medical student from Urelu and student leader who joined the LTTE in 1983 and quickly became first its propagandist and then political head of Jaffna. IN 1987 he fasted to death in protest against the actions (or rather lack of action) of the IPKF in Jaffna and violations of the ceasefire. He focused on recruiting young women for the movement.

Today it is assumed that between 30-40% of LTTE fighters are women who are organized in separate women’s regiments under female leadership. In the suicide cadres, the number of men and women are said to be equal (though this is questionable: in the lists of martyrs given out every year on Heroes’ Day, there are still far fewer women listed than men).

Individual reasons for joining the LTTE varied considerably. In the early 80s women became members of the LTTE (and other militant organisations) to escape or pre-empt rape by Sinhalese or Indian soldiers. Others joined precisely because they had been raped. This led to the claim that rape was the only reason for women to join a militant movement or become a suicide bomber (de Mel, 2004).10 This, however, appears to be an oversimplification. Rape might have been a reason to join or turn into a suicide bomber in some cases, but not the major one. Besides when the character of the armed struggle and the organization changed in late 80s and 90s from a guerrilla group to a virtually conventional force, women’s motivations to join the organization also changed. They currently cover a wide spectrum: the efficiency and appeal of LTTE propaganda to come to the aid of the motherland made young women want to be part of the movement; yet equally frequently it was the experience of violent attacks by the Sri Lankan Army, injury and death of near relatives and friends that induced them to violent struggle. One young student told:

‘In 1997 the Sri Lankan Army flew a bomb attack on the school I was attending. We ran into the jungle and some of my class mates and teachers died. The next day most of our class went to the LTTE camp to join. I was 16 at the time. Unfortunately they rejected me as too small and weak. They told me to go on studying and then work for the country in some other way (personal communication, 2007).’

Military tank captured by Tiger women in Muhamali battle, Oct. 2006

In many cases, however, particularly in the 90s and after 2002, it was simply the desire for adventure or to do something ‘cool’ which all her peers were doing as well that made young, sometimes underage, girls to show up as recruits in the LTTE camps. In more serious cases they sometimes tried to escape a family situation that had become unbearable: either because of an alcoholic, abusive father, extreme poverty or the threat to be forced into marriage with somebody they did not like. A member of the SLMM, the Sri Lanka Monitoring Mission who was in charge of returning underage LTTE members to their families, told me that sometimes she did this with a heavy heart, since the family situation was not such that she would willingly expose them again to a broken home. Most of these children, however, or so she said, came from quite good and intact families, but thought it the ‘in thing’ to join the LTTE, since all their friends did the same. We agreed that it could be compared to the fashion of body piercing in Europe, which induces similar horror in parents (personal communication 2003). Frequently it is impossible to tell why a particular woman joined the movement, and general explanations cannot be given. Most women I talked to cited the experience of oppression by the Sinhalese armed forces or the persuasive power of LTTE leader V. Prabhakaran’s speeches. Some followed the call to arms in order to enable an elder or younger brother to study. This was at the time when the LTTE asked for one child of each family to join the movement.

With the growing power of the LTTE female fighters have become increasingly visible. They have remained easily identifiable in public life after the ceasefire due to their distinctive ‘civil uniform’: loose dark trousers, a long men’s shirt in sober colours tightly belted and short hair or long plaits would tightly round the head. Nothing could be more different from the traditional dress of Tamil women and girls: the sari or long skirt and blouse and long plaits or a bun adorned with flowers. Only when they leave the movement to return to civil life do they revert to more or less traditional clothes: long skirts, shalwar kameez or jeans and shirts. Former female fighters are seldom seen in saris, except for functions or in the temple. The ressing habits are a clear statement and they give the lie to rumours that made the rounds in the 80s and early 90s, that the LTTE had put out a leaflet to force women to wear only saries on pain of severe punishment (de Mel, 2001).11

As soon as the first female fighters fell victim to armed battle, they were given the status and title of Mavirar, as was done for their male comrades. The term may be translated as Great Hero, it is, however, mostly rendered as ‘martyr’ by the LTTE. And thus we come to the female martyrs.

Female Martyrs

The first to be granted this title was 2nd Lt. Malathy (Malthi, Malathi) from Mannar. She is honoured by statues and monuments in Killinoichi and the day of her death has become Tamil Eelam Women’s Awakening Day (www.tamilnet.com). Her real Catholic name was Cakayacili Peturuppillai. She died on 10th October 1987 at the age of twenty in a battle between the LTTE and the IPKF at Kopay by her own hand. Her comrade Janani told how she was wounded in both legs and could not escape, so she sent the other women away and took cyanide (Balasingham, www.tamilnation). Malathy was only the first in a long line of women martyrs of the LTTE like Major Kecari who died in the attack at Elephant Pass. The first and the early martyrs commonly attain a particularly high status. Brigades and Regiments are named after them. Unfortunately, none of the eloges and articles on Malathy tell us anything about her reasons to join the LTTE or about her biography. She seems to have come on the scene like Aphrodite, born of foam. On the other hand, every year on her memorial day, it is reported that her parents publicly garland her tomb stone and her statue (www.tamilnet).

On another level altogether is Annai Pupati (Mother Pupati). Her full name was Kanapatipillai Pupati, and she died in a temple in Batticaloa on 19th April 1988 at the age of 56 – after refusing both food and fluids for 30 days. She seems, according to all accounts, to have been a very inconspicuous, traditional Tamil woman, married at twelve and widowed soon after. She remarried a widower with three children, something not totally unheard of in Jaffna, and had altogether ten children. She turned radical after two of her sons had been killed by the army and a third been arrested and tortured in Boosa camp. She became a member of the Mothers’ Front in Navatkeni, a women’s group who non-violently protested against the army occupation and violation of human rights and enquired after the fate of ‘disappeared’ Tamil youth in army and police camps. On 19th March 1988 she commenced her fast unto death in protest against the actions of the IPKF and to demand a ceasefire and negotiations between the combatants (www.tamilnation.org). She is honoured by special ceremonies every year in the Northeast and in Jaffna.

I have dealt with the question of martyrs and gender differences in the evaluation of martyrs in another place and shall therefore only briefly discuss the question here (Hellmann-Rajanayagam, 2008a). To put it shortly, men become pure by dying a martyr’s death, women retain their purity. While this applies particularly to the Indian cultural area, the same concept is not unknown even in the Christian tradition. In India, this becomes especially clear in the concept of theSati who immolates herself after her husband’s death on his funeral pyre. For satis, occasionally hero or memorial stones were erected like for a fallen warrior. This statement is, however, problematic within the context of LTTE ideology, since it demands chastity (karpu) from both sexes. Karpu is here understood less as virginity and/or sexual purity, than as (sexual) self control and restraint (Schalk, 1994; Viswanathan-Peterson, 1998).12 As a secular movement (that is how it portrays and presents itself quite aggressively in public) it strictly rejects the concept and practice of Sati. Female and male martyrs are honoured in exactly the same way: through monuments, memorial stones and statues and anniversary celebratins on the day of their death each year.

Suicide Bombers

Suicide assassins (karumpuli), though labelled and honoured as martyrs (Mavirar) by the LTTE and often equated in the media, particularly when dealing with Islamic violence, must be distinguished from the latter. All fighters who fall in battle or during special actions, are martyrs. Thus, suicide attackers count as martyrs as a matter of course, but they belong in another category. Only occasionally named monuments are erected for them, and in many cases, suicide attackers remain anonymous. Named monuments exist, like for normal martyrs, for the first suicide tigers, Sivakumaran and Capt. Miller. The most well known suicide bomber, however, never got a monument: Dhanu, who allegedly assassinated Rajiv Gandhi (Sarvan, 1998).13 Officially, the LTTE has never acknowledged her as one of their own. Suicide bombers or, to give them their proper name, Black Tigers are selected and trained specially (Hellmann-Rajanayagam, 2007). They apply of their own volition, but very few are chosen. They are taught to consider their lives as weapon and as a special gift: tankotai,14 which they donate for a higher goal, viz. the liberation of the Tamil Motherland. Reason and goal of dying are national, not religious ones, whether for men or for women (Hellmann-Rajanayagam, 2005). It is important to emphasise this point: moral or religious reasons are never adduced for suicide attacks, we find no idea of karma, of rebirth or entry into a paradise. The only reward for a black Tiger is the idea of contributing to the liberation of the motherland. This is a decisive and conspicuous difference to the ideals current in Islamic militant movements (Victor, 2003).

Ideals and Role Models

Before discussing the question of women’s emancipation or ‘empowerment’ through militancy, it will be instructive to investigate to which ideals or role models the LTTE harks back in its efforts to bring women into the organization. For the struggle in general and its support by women classical heroic literature is consciously, albeit, selectively, chosen. The Purananuru furnishes enough blood-soaked examples for this kind of event.15 But classical literature cannot be used to justify the recruitment of women nor can religious models be applied. Active combat by women is not sanctioned by tradition and is indeed considered and propagated as something new and somehow a break with the past. Instead, the Indian freedom struggle provides suitable examples to follow. This applies both to the struggle led by Gandhi and the Indian National Congress and – even more – to the movement led by Subhas Chandra Bose and the Indian National Army. The INA is the Indian organization on which the LTTE consciously wants to model itself, and this applies also to its treatment and employment of women. The INA contained a very active women’s regiment, the Rani of Jhansi regiment which was led by Lakshmi Sahgal nee Swaminathan, a Tamil doctor from Malaya. She drew numerous Tamil women into the INA, among them Bupalan Rasammah (Gawankar, 2003; Ward Fay, 1995). This regiment gave women for the first time, according to their own statements, a feeling of being humans and not redundant and superfluous chattels. Similar statements we have from Tamil men from Malaya as well, who gave this as a reason to join the INA: they were for the first time in their lives treated as human beings.

Women Fighters: Empowerment

The significance of female militancy for women’s emancipation is fiercely debated. To set the scene for the discussion, I describe here several of my ‘encounters with tigresses’:

- Shortly after the ceasefire agreement in February 2002 I could, after a long interruption, again travel to the Tamil areas. LTTE cadres were conducting me to the town of Mullaitivu when out jeep’s axle broke roughly half-way. Until a new vehicle could be organized, I was conveyed (a rather highflown term for a bumpy journey riding pillion on the motorcycle of the camp commander into the interior of scrub jungle) to a women’s camp near Utaiyarkadu. The commander was 28 years old Lt. Col.Bhavaniti. She had fought in the battle of Elephant Pass in 2000, when the LTTE overran the Sri Lanka Army base camp there and reconquered the pass with heavy casualties for the Sinhalese and in Pallai some months later. She had commanded a battalion of 500 soldiers. She led the Kutti Sri Regiment16 and had been a member of the LTTE since 1993. She explained that she had sustained hundred casualties, both dead and injured, in the various battles. In early 2003 the camp had been virtually closed down, only ten fighters were still administering it. Bhavaniti was extremely pleased by my visit and by the interest I took in the camp and in her personal story and insisted that I could not leave before I had had lunch with her. She came across as a very pleasant, self-assured young women with a natural authority. All women in the camp wore the typical uniform of the tigresses; only one girl was dressed in skirt and blouse on account of a landmine having torn of her calf. She told me that she was 21 years old and had taken part in battles for Elephant Pass and in Chavakacheri in 2001 (if this was the case, she must have been recruited at an age of 18 or even 17). Bhavaniti hailed from Chavakacheri where most of her family still lived. Some of her brothers and sisters had gone to live in Canada and Switzerland. She herself stayed in a pleasantly furnished little bungalow with floor and steps constructed from ammunition boxes on which one could still discern the writing ‘Sri Lankan Armed Forces’. She was happy about the ceasefire, but ready to go into battle again for her leader and the country. Once peace came she would like to study computer science. Would she want to marry? Oh yes, surely, one day, but not yet. The entrance into the camp was strictly controlled not so much for reasons of security, but for those of propriety: only women could enter the sanctus sanctorum, the commander’s bungalow. The young men accompanying me had to wait beyond the fence in the visitors’ room which simultaneously functioned as a memorial room for the founder-martyr of the regiment: Kutti Sri. It was, as one of the SLMM-officers later put it, a rather monastic atmosphere with the commander as the mother Abbess. Not a bad comparison: both the atmosphere of dedication and the segregation of males and females reminded one of monastic conditions. The military training likewise is conducted in a strictly segregated manner, even though the trainers of the women cadres are sometimes still male fighters (Trawick 1999)17

- I had later occasion to meet Thamilini, the leader of the women’s wing of the LTTE, and her assistants, several times on each of my subsequent visits between 2004 and 2007. Thamilini is a very bubbly and energetic young lady in her mid-thirties belonging to a Karaiyar family from the Vanni. The Kariyar are the second largest caste among the Sri Lankan Tamils, the highest and most numerous caste being the Vellalar. The Kariyar are originally fisher people and for centuries funished the military forces of the Jaffna kings. They have a reputation of pride and ferocity. They do not fit easily in the caste hierarchy of Tamil Sri Lanka, since they consider themselves as standing and acting outside or alongside it (Pfaffenberger, 1982; Hellmann-Rajanayagam, 2007a, 2004). A large number of them are Catholics. Quite a number of the female fighters are, by their own statements, Karaiyar from very humble backgrounds (Kalaivilly, 2004). At the time of the first interview Thamilini had just finished a very active military career and had got involved in politics to the extent that she supported the election campaign of the female candidates of the TNA, the Tamil National Alliance, especially Pathmini Sithamparanathan. She also supported or was a member in several women’s organisations and NGOs. She has, however, not left the LTTE yet. At the last meeting she stated matter-of-factly that she would probably have to take part in military operations again soon.

In Thamilini’s view the war has provided a significant change of roles for women, this could, however, not be considered final. The gains of the war would have to be cemented in peace negotiations – if ever they would be resumed – through a new definition of the role of women and in legislation. A most interesting development in this regard was the close contacts and cooperation of the LTTE women’s wing with the Social Scientists’ Association in Colombo and one of its fellows, Kumari Jayewardene. These contacts were kept up long after the ceasefire had been suspended and many other contacts had broken down. Thamilini emphasized that she was less interested in the abolition of dowry, but in its correct, i.e. traditional interpretation according to the Tesavalamai, whose regulations have been outlined above (Thamilini, 2004, 2004a, 2007).

- LTTE women, who have left active service may remain in the movement or return to civil life. In the former case they may become members of the politbureau like Thamilini, work in the Peace Secretariat, like Selvy, its Human Rights spokeswoman, the PDS, like Gita, or the TRO, as principals of LTTE-children’s homes, like Jayanani or, as was the case especially after the tsunami, they work as doctors in the Tilipan Primary Health Centres and other health institutions with limited means but great dedication. 40% of Tamil Eelam Police personnel are women, and many health, education and administrative institutions are led and run by former LTTE women with great efficiency. LTTE women are marked off from the remainder of the female population not only by their dress and hair style, but much more by their demeanour and comportment. They spread an aura of determination and self assurance which is not commonly shown by women in Sri Lanka publicly. Margaret Trawick (1999), whose study is one of the first and most comprehensive ones about women members of the LTTE claims that the women fighters still follow old role patterns in interactions with men as well as with others of their own sex. Only during active fights, which for them are a necessary task to be fulfilled as well as possible including the annihilation of the adversary, she says, they become different personalities (Trawick, 1999). While it is true that frequently traditional patterns of interaction are still enacted, especially in encounters with superiors, the self-confidence and self-assurance of LTTE women in all areas of daily life is visible: they would, e.g. never hesitate to move anywhere alone even at night, something unthinkable for even the most confident Tamil woman in Jaffna and Killinochi. While men would not dare to trifle with these women, they are nothing like their description in the Sinhalese media: dour, humourless fighting robots, but rather pleasant-spoken, merry and friendly young women, who treat the inquisitive visitor with great kindliness and courteous firmness.

Autonomy Through Militancy?

LTTE women cadres trained for police duty, Jaffna 1994?

Can membership in a militant group at all have an emancipatory effect? The segregated training and fighting situation of the LTTE&s regiments and the participation of women in suicide attacks have attracted reproaches that the LTTE’s concern for women’s liberation were dishonest and superficial and that it tried to recruit women merely since there were, for various reasons, not enough young men to join. Besides, sexual segregation and forced recruitment were no means to overcome women’s disadvantages (Coomaraswamy, 2005).18 It is not quite easy to follow these arguments if one at the same time considers another one often voiced (frequently by precisely the same commentators) that describes the LTTE as one of the most forceful and most committed militant movements existing. A movement that is able to generate a willingness for struggle and sacrifice to such an extent as the LTTE, without the prospects of future rewards or a glorious hereafter, would be hard put to it to use unlimited coercion to recruit new blood.

Sexual segregation may be (or may have been) a first step to get women on the same level as men (de Mel, 2001, Trawick, 1999).19 A more grievous accusation has been that recruitment into militant organisations in order to exert violence cannot be a true move in the direction of women’s liberation (de Cataldo-Neuberger/Valentini, 1996). This argument proceeds from the above-mentioned assumption that women are by nature peaceful and virtually born for mediation, peace-building and healing. Within the specific context of Sri Lankan Tamil women, Darini Rajasingham-Senanayake (2001) and Adele Balasingham (1998) have, from widely diverging perspectives, shown that many of the women joining the LTTE feel autonomous and able to decide about their destiny for themselves for the first time in their lives. They retain this feeling and this attitude on their return to civil life. We earlier mentioned the same happening in the INA, when many Tamils felt for the first time acknowledged and treated as humans by a movement considered fascist and treasonable by the British.

A New Age of Woman?

Susanne Schroter has recently outlined the reasons why Muslim women might become suicide attackers (Schroter, 2008, forthcoming). These reasons turn on social marginalization and oppression or on perceived^sexual-shame and guilt as well as increasingly religious motivations. The latter is in contrast to the women, like Laila Khaled who played a prominent role in the militant Palestine movement in the 70s, and who were secular and autonomous. Secular and autonomous is also fitting description of Tamil Tigresses (whether they are religious in private life or not); The LTTE does not recruit women to expiate some alleged disgrace, but to fight for the motherland. Suicide attacks are incidental, not, as in Islamic movements, an end in themselves. Tigresses do precisely not become Satis by other means. Even if sometimes their reasons for joining armed struggle derive from a difficult or broken family situation, they are not triggered by banishment from the family due to some alleged misdemeanor or wrong-doing. Surviving women fighters return to civil life, become professionals, marry and have children. But: they mostly choose their husbands instead of bowing down to their parents’ wishes. Some, like Thamilini and Bhavaniti, reject marriage for the time being, even though, as Kumari Jayawardene emphasizes, familial pressure to marry is often very strong even for women Tigers: they have more important things to do and the taste of freedom is addictive. Participation in armed struggle involves overwhelmingly an element of voluntariness, much less despair about the hopelessness of personal circumstances.

To put it briefly, Tamil women join the Tigers not to die, but to fight. Death is taken into account, but is not necessarily anticipated. This is a decisive difference to the situation of Muslim women (de Mel, 2001; Schroter, 2008; Victor 2003).20

The problem for female LTTE-fighters lies elsewhere. It is two fold: on the one side a clear awareness of a tradition and social ideology disadvantageous to women that has been exacerbated by British legislation of the late 19th century. LTTE women want to re-establish freedoms granted them in pre-colonial times. On the other side, and Tamilini thinks this is far more serious – we see that female LTTE members are not really acknowledged as role models for most Tamil women in Sri Lanka: they are being admired, but they are not emulated. They seem to be predestined to do things for women that other women are not able or not prepared to achieve. Thamilini put it pithily: most women still clin to the KKK-ideal.21 Moreover, there are reports that many families do not like to marry their sons to female Tigers (which is not easily to be wondered at!).

Tigresses act, like the goddess, outside of a social structure handed down for centuries and thus, cannot be role models. Many women feel uncomfortable in the presence of Tigresses, maybe because they feel inadequate themselves (or because they do not consider them real women?). Or it might be because many female fighters, like male ones belong in the Karaiyar caste. On the other hand some Tigresses seem to nurse slight contempt for the KKK-women who are trapped in out-dated ideas and anxieties. Yet these attitudes, Thamilini thinks, are the ones most difficult to overcome. The Tigresses thus perceive the problems of transition from a war to a peace culture very acutely, but they are still in the process of envisaging how to achieve this transition in a manner that is just and satisfactory for women.

So, we come around again to the persistent question whether membership in radical groups can be liberating or not. It is impossible to decide on this question generally and finally, and the debate will probably rage for a long time to come. At the end, however, a somewhat uncomfortable observation: even in Germany, the rethinking of customary female roles only really began with 68ers’ movement and the establishment of the violent Baader-Meinhof-group. Is then, to misquote Herodot, battle really the mother of all things?

Notes

Note 1: Chenoy argues, that feminist argument of the ‘naturally peaceful woman’ is just the obverse of the male, patriarchal view that peaceful men are weak and feminized.

Note 2: In the Cilappatikaram, however, only Kannaki is described as such. Her husband Kovalan’s mistress Madhavi, is both educated and accomplished as well as independent and knowledgeable.

Note 3: Though this might have less to do with the wife being a woman, but with the women being a wife: Indira Viswanathan-Peterson describes how in many folk tales the bond between brothers and sisters is the strongest love bond, where the wife only comes in as a necessary, but malignant and disturbing factor. This idea may be due to the Dravidian kinship system where close cousins are the ideal marriage partners.

Note 4: Though reformer is a misnomer’ Navalar put across an extremely traditional, one could say reactionary view of women and their role, which makes his advocacy for female education the more remarkable.

Note 5: Between 1942 and 1980 there not one Tamil woman was a member of Parliament.

Note 6: For years after independence, the figure varied between 1% and 3%.

Note 7: In Tamilnadu, as well, the institution of dowry worked out rather differently from the North.

Note 8: De Mel, while not denying the changes, claims that LTTE patriarchy claws back its power by redefining itself and throwing women back on their reproductive role. This might be true or not, but it is certainly unique: it has happened in Germany after WWII as well.

Note 9: Margaret Trawick puts it more sharply: ‘Women have now decided that talking about their problems will never put an end to their problems. They have to challenge.’

Note 10: De Mel describes pointedly the dangers and the inadmissibility of linking these women’s reasons for conducting suicide attacks exclusively to motivations of sexuality/sexual violation. Apart from anything else, it would deny her agency and personality. She speaks of about 64 known-because dead- female suicide cadres.

Note 11: The reference for the quote is Sitralega Maunaguru in another study. This essay again quotes from another publication: I have not been able to trace the original of the quote anywhere and have a strong suspicion that it was either a fake or never existed.

Note 12: Viswanathan-Peterson argues similarly, that karpu as ‘learned inward control’ is unrelated to marriage and denotes a source of sacred power.

Note 13: Instead, she has acquired an eternal literal life elsewhere: in short stories and plays. All these suffer from the fact that none of the authors has ever met, let alone talked to, Dhanu in the flesh, and that they harp on the sexual angle. De Mel, who has written extensively about women suicide cadres has met and interviewed none of them, she relies on mediated interviews and reports of former LTTE women who have turned hostile to the movement. It seems that even after the ceasefire, with few exceptions, none of these authors ventured into the Tamil areas for a first hand look and to take into account the changes the ceasefire had wrought.

Note 14: This is a word play on the Tamil term for suicide: tarkolai =killing of self, whereas tankotai is translated as gift of self.

Note 15: ‘Greater joy than on the day I bore him I have today from my son’. A mother on finding her son cut in four pieces on the battlefield.

Note 16: Named after another martyr of the movement.

Note 17: ‘It is Tiger policy for male and female combatants to treat one another with respectful distance.’

Note 18: This was the strongly voiced opinion of Radhika Coomaraswamy, former special UN-envoy for violence against women and children.

Note 19: While de Mel laments the sexual containment and the corresponding emphasis on women’s sexuality and its redirection towards militancy, she overlooks in this partly quite observant outline that the same ‘eroticising of the martial’ (p. 207) occurs in purely male movements and armies since time immemorial. At the least this segregation would prevent abuse of women as has (been alleged to have) happened in the US armed forces. Trawick puts the whole matter into a suitable perspective: ‘Such observations belie the rumours that members of the LTTE are either sexually repressed or promiscuous. I would suggest that investigations into the sexual life of the LTTE members will yield no exciting discoveries.’

Note 20: de Mel questions this. She considers the element of dutiful sacrifice and martyrdom overriding even for Tamil women. Here, as often elsewhere, there seems to be confusion and conflation of female fighters, suicide cadres, and martyrs.

Note 21: A derogatory term employed by the feminist movement in Germany during the 70s and 80s: Kinder, Kuche, Kirche = Children, Kitchen, Church. Thamilini has visited Germany several times and discussed with women’s groups, so the term was familiar to her. She used it with considerable amusement.

References

Balasingham, Adele (1998). Will to Freedom – An Inside view of Tamil resistance, London: Fiarmax.

Balasingham, Adele Ann (1994). Unbroken Chains – Explorations into the Jaffna Dowry System,. Jaffna: Malathi Press.

Balasingham, Adele Ann (1993). Women Fighters of Liberation Tigers, Jaffna: Tamil Eelam, Thasan Printers.

Beck, Brenda E.F. (1982). The three twins – The telling of a South Indian Folk Epic, Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Bloom, Mia (2005). Dying to Kill – The Allure of Suicide Terror, New York: Columbia University Press.

Canmukalinkan, N (2002). Panpattin camukaviyal, Tellippalai: Nakalingam Nulalayam.

Chenoy, Anuradha M (2004). Militarism and Women in South Asia, New Delhi: Kali for Women.

Chenoy, Anuradha M (2004). Gender and International Politics: The intersections of patriarchy and militarization. Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 11 (1): 27-42.

Coomaraswamy, Radhika (2004). Violence, Armed Conflict and the Community. Jayaweera, Swarna: Women in Post Independence Sri Lanka, New Delhi: Sage, pp. 80-98.

de Cataldo Neuberger, Luisella and Valentini, Tiziana (eds) (1996). Women and Terrorism, New York: St Martin’s Press.

de Mel, Neloufer (2001). Women and the Nation’s Narrative, Gender and Nationalism in Twentieth Century Sri Lanka, Colombo: Social Scientists’ Association.

de Mel, Neloufer (2004). Body Politics (Re)Cognising the Female Suicide Bomber in Sri Lanka. Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 11 (1): 75-93.

Gawankar, Rohini (2003). The Women’s Regiment and Capt Lakshmi of INA. An Untold Episode of NRI Women’s Contribution to Indian Freedom Struggle. New Delhi: Devika Publication.

Goonesekere, Savitri (2002). Constitutions, Governance and Law. Jayaweera, Swarna, Women in Post-Independence Sri Lanka, New Delhi: Sage, pp 41-78.

Gopinath, Aruna, National Archives of Malaysia, Shivadas, P.C. (eds) (2007). Footprints on the Sands of Time: Rasammah Bhupalan – a Life of Purpose. Kuala Lumpur.

Hellmann-Rajanayagam, Dagmar (1994). The Tigers – Armed Stuggle for Identity, Beitrage zur Sudasienforschung 157, Stuttgart: Franz Steiner (reprint 1998).

Hellmann-Rajanayagam, Dagmar (2004). From Differences to Ethnic Solidarity among the Tamils, in Morrison, Barrie et al. (eds), Struggling to Create a New Society: Sri Lanka in the Era of Globalization, New Delhi: Sage, pp. 102-125.

Hellmann-Rajanayagam, Dagmar (2008). God My Sister. Fleschenberg, Andrea and Hellmann-Rajanayagam, Dagmar (eds), Goddesses, Heroes, Martyrs, Berlin: Lit-Verlag, forthcoming.

Hellmann-Rajanayagam, Dagmar (1989). Arumuka Navalar: Religious Reformer or National Leader of Eelam? Indian Economic and Social History Review, 26 (2): 235-257.

Hellmann-Rajanayagam, Dagmar (2007). Auggewahlt fur Selbstmordkommandos: Die Schwarzen Tiger, Wissenschaft und Frieden, 1: 18-21.

Hellmann-Rajanayagam, Dagmar (2008a). The Living Sacrifice. Fleschenberg Andrea and Hellmann-Rajanayagam, Goddesses, Heroes, Sacrifices, Berlin: Lit-Verlag, forthcoming.

Hellmann-Rajanayagam, Dagmar (2005). And Heroes Die: Poetry of the Tamil Liberation Movement in Northern Sri Lanka, South Asia, new series, 28(1): 112-153.

Hellmann-Rajanayagam, Dagmar (2007a). Von Jaffna nach Kilinochchi-Ursprunge und Entwicklung ethnischer Konflikte in Sri Lanka seit dem 19. Jr Wechselwirkungen religios-nationaler Erneuerungsbewegungen und britischer Verwaltungs-und Verfassungspolitik, Ergon: Wursburg.

Ilankovatikal arulicceyta Cilappatikara mulamum arumbattavuraiyum atiyarkkunallaruraium (1978). Madras: U.Ve Caminataiyar Nulnilaiyam.

Jayawardene, Kumari (2000). Nobodies to Somebodies, The Rise of the Colonial Bourgeosie in Sri Lanka, Colombo: Social Scientists’ Association.

Jayawardena, Kishali Pinto and Kodikara, Chulani (2002). Sri Lanka, Tambiah, Jasmin (ed), Women and Governance in South Asia: Re-Imagining the State, Colombo: ICES.

Mukta, Parita (2004). Gender, Community and Nation – The Myth of Innocence, In, Jacobs Susie M, Jacobson Ruth, Marchbank Jennifer (eds) States of Conflict: Gender, Violence and Resistance, London: Zed Books, pp. 163-178.

Mutukistna H.F. (1862). The Thesavalamai or the Laws of Customs of Jaffna, Jaffna.

Perera, Morina and Chandrasekera, Rasika (eds) (2005). Excluding Women. The Stuggle for Women’s Political Participation in Sri Lanka. Colombo: Social Scientists’ Association.

Pfaffenberger, Bryan (1982). Caste in Tamil Culture, Foundations of Sudra Domination in Tamil Sri Lanka, Bombay.

Purananuru (poems) 276, 277, 278, 270.

Rajasingham-Senanayake, Darini (2001). Ambivalent Empowerment Midst Tragedy of Tamil Women in Confict, In Manchanda, Rita (ed), Women In Conflict, New Delhi, pp. 104-130.

Sarvan, Charles (1998). Appointment with Rajiv Gandhi, In Roberts, Michael (ed), Sri Lanka: Collectives Identities Revisited, vol.2, Colombo: Marga, pp. 357-361.

Schalk, Peter (1994). Women Fighters of the Liberation Tigers in Tamil Ilam – The martial feminism of Atel Palacinkam. South Asia Research, 14(2): 163-183.

Schroter, Siusanne (2008). Female leadership in Islamic societies, past and present. In Fleschenberg/Hellmann-Rajanayagam, Goddess, Heroes, Sacrifices, Berlin: Lit-Verlag (forthcoming).

Skaine, Rosemaries (2006). Female Suicide Bombers, London: McFarland.

Thambiah, H.W. (1950). The Laws and Customs of the Tamils of Jaffna, Jaffna.

Trawick, Margaret (1999). Reasons for Violence: A preliminary ethnographic account of the LTTE. In, Gamage, Siri and Watson, I.B. (eds), Conflict and Community in Contemporary Sri Lanka, ‘Pearl of the East’ or the ‘Island of Tears’?, New Delhi.

Victor, Barbara (2003). Army of Roses: Inside the World of Palestinian Women Suicide Bombers, New York: Rhodale Press.

Viswanathan-Peterson, Indira (1998). The Tie that Binds: Brothers and Sisters in North and South India, South Asian Social Scientist, 4(1): 25-52,

Ward Fay, Peter (1995). The Forgotten Army: India’s Armed Struggle for Independence 1942-1945. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Whitworth, Sandra (2006). Men, Militarism & UN Peacekeeping: A Gendered Analysis, New Delhi: Manohar.

Interviews and Conversations

Coomaraswamy, Radhika: Former Special UN-envoy for Violence against women and children, August 2005.

Kalaivilly, Yo: Chairwoman Women’s wing, Jaffna, 25th February 2004, SLMM officer, March 2003.

Thamilini, Su: Leader, Women’s political wing LTTE, 2nd March 2004, 5th March 2004 and 30th August 2007.

****

Thank you so much for this article.