by Sachi Sri Kantha, January 27, 2023

Gandhi on his death-bed

Gandhi in death-bedJanuary 30th 2023 marks the 75th death anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi. To commemorate the anniversary, first I provide below period items from two esteemed American print sources, announcing Gandhi’s death. Robert Trumbull’s report from New Delhi, with the caption ‘Gandhi is killed by a Hindu; India shaken, world mourns; 15 die in rioting in Bombay’, appeared in the New York Times (Jan 31, 1948). An unsigned news report appeared in the Time magazine of Feb. 9, 1948, included two foot notes as well.

Secondly, I provide a summary of pre-assassination and post-assassination calendar of events related to Gandhi’s activities in his final 30 days and the assassination trial conducted in 1948 and 1949. The details available in two recent Gandhi biographies (authored by Martin Green and Ramachandra Guha), a psychological biography (authored by Erik Erikson) and a memoir (by William L. Shirer) in my Gandhi-related collection leave much to be desired on the post-assassination events of 1948 and the treatment meted out to Gandhi’s assassin and other plotters of the crime, all of whom were Hindus. As such, I had prepared this summary for my own education, which I share with the readers. To compile this summary, I had to depend on the books authored by Justice Gopal Das Khosla (one of the appeal judges in the Gandhi assassination trial), Gopal Godse – the sixth accused in the trial, and a sibling of the Gandhi assassin, as well as that of C.B. Dalal, a Gandhi chronicler.

Gandhi is killed by a Hindu; India shaken, World mourns; 15 die in rioting in Bombay

[Robert Trumbull, New York Times, Jan 31, 1948, pp. 1 and 2]

New Delhi, India, Jan.30 – Mohandas K. Gandhi was killed by an assassin’s bullet today. The assassin was a Hindu who fired three shots from a pistol at a range of three feet.

The 78 year old Gandhi, who was the one person who held discordant elements together and kept some sort of unity in this turbulent land, was shot down at 5:15 pm as he was proceeding through the Birla House gardens to the pergola from which he was to deliver his daily prayer meeting message.

The assassin was immediately seized.

Nathuram Godse (lt) and Narayan Apte – first two accused hanged in Nov 15, 1949

He later identified himself as Nathuram Vinayak Godse, 36, a Hindu of the Mahratta tribes in Poona. This has been a center of resistance to Gandhi’s ideology.

Mr Gandhi died twenty five minutes later. His death left all India stunned and bewildered as to the direction that this newly independent nation would take without its ‘Mahatma’ (Great Teacher).

The loss of Mr Gandhi brings this country of 300,000,000 abruptly to a crossroads. Mingled with the sadness in this capital tonight was an undercurrent of fear and uncertainty, for now the strongest influence for peace in India that this generation has known is gone.

[Communal riots quickly swept Bombay when news of Mr Gandhi’s death was received. The Associated Press reported that fifteen persons were killed and more than fifty injured before an uneasy peace was established.]

Appeal made by Nehru: Prime Minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, in a voice choked with emotion, appealed io a radio address tonight for a sane approach to the future. He asked that India’s path be turned away from violence in memory of the great peacemaker who had departed.

Mr Gandhi’s body will be cremated in the orthodox Hindu fashion according to his often expressed wishes. His body will be carried from his New Delhi residence on a simple wooden cot covered with a sheet at 11:30 tomorrow morning. The funeral procession will wind through every principal street of two cities of New and Old Delhi and reach the burning ghats on the bank of the sacred Jumna River at about 4 pm. There the remains of the greatest Indian since Gautama Buddha will be wrapped in a sheet, laid on a pyre of wood and burned. His ashes will be scattered on the Jumna’s waters, eventually to mingle with the Ganges where the two holy rivers meet at the temple city of Allahabad.

These simple ceremonies were announced tonight by Pandit Nehru in respect to Mr. Gandhi’s wishes, although many of the leaders desired that his body be embalmed and exhibited in state. India will see the last of Mr Gandhi as it saw him when he lived – a humble and unassuming Hindu.

News spread quickly: News of the assassination of Mr Gandhi – only a few days after he had finished a five day fast to bring about communal friendship – spread quickly through New Delhi. Immediately there was spontaneous movement of thousands to Birla House, home of G.D. Birla, the millionaire industrialist, where Mr Gandhi and his six secretaries had been guests since he came to New Delhi in the midst of the disturbances in India’s capital.

While walking through the gardens to this evening’s prayer meeting Mr Gandhi had just reached the top of a short flight of bricksteps, his slender brown arms around the shoulders of his grand daughters, Manu, 17 and Ava, 20.

Someone spoke to him and he turned from his granddaughters and gave the appealing Hindu salute – palms together and the points of the fingers brought to the chin as in a Christian attitude of prayer.

At once a youngish Indian stepped from the crowd – which had opened to form a pathway for Mr Gandhi’s walk to the pergola – and fired the fatal shots from a European-made pistol. One bullet struck Mr Gandhi in the chest and two in the abdomen on the right side. He seemed to lean forward and then crumpled to the ground. His two granddaughters fell beside him in tears.

Crowd is stunned: A crowd of about 500, according to witnesses, was stunned. There was no outcry or excitement for a second or two. Then the onlookers began to push the assassin more as if in bewilderment than in anger.

The assassin was seized by Tom Reiner of Lancaster, Mass., a vice consul attached to the American Embassy and a recent arrival in India. He was attending Mr Gandhi’s prayer meeting out of curiosity, as most visitors to New Delhi do at least once.

Mr Reiner grasped the assailant by the shoulders and shoved him toward several police guards. Only then did the crowd begin to grasp what had happened and a forest of fists belabored the assassin as he was dragged toward the pergola where Mr Gandhi was to have prayed. He left a trail of blood.

Mr Gandhi was picked up by attendants and carried rapidly back to the unpretentious bedroom where he had passed most of his working and sleeping hours. As he wastaken through the door Hindu onlookers who could see him began to wail and beat their breasts.

Less than half an hour later a member of Mr Gandhi’s entourage came out of the room and said to those about the door:

‘Bapu (father) is finished.’

But it was not until Mr Gandhi’s death was announced by All India Radio at 6 pm, that the word spread widely.

Digambar Badge (who became a prosecution witness)

Assassin taken away: Meanwhile the assassin was taken to a police station. He identified himself as coming from Poona.

It was remarked that the first of three attempts on Mr Gandhi’s life was made in Poona on June 25, 1934, when a bomb was thrown at a car believed to be Mr Gandhi’s. Poona is a center of the extremist anti=Gandhi orthodox Hindu Mahasabha (Great Society).

The second possible attempt to assassinate Mr Gandhi was by means of a crude bomb planted on his garden wall on Jan 20 of this year.

The only statement known to have been made by the assassin was his remark to a foreign correspondent: ‘I am not at all sorry.’

He is large for a Hindu and was dressed in gray slacks, blue pullover and khaki bush jacket. His pistol, which was snatched from him immediately after the shooting by Royal Indian Air Force Flight Sergeant D.R. Singh, contained four undischarged cartridges.

Lying on a wooden cot in his bedroom, Mr Gandhi said no word before his death except once to ask for water. Most of the time he was unconscious. When he was pronounced death by his physician weeping members of his staff covered the lower half of his face with a sheet in the Hindu fashion and the women present sat on the floor and chanted verses from the sacred scriptures of the Hindus. Those who could see these ceremonies through the windows knew then that Mr Gandhi had expired.

Pandit Nehru arrived at about 6 o’clock. Silently and with burning eyes he inspected the spot where Mr Gandhi was shot and then went into the house without a word. Later he stood high on the front gate of Birla House and related the tentative funeral arrangements to several thousand persons gathered in the street and blocking all traffic. His voice shook with grief and hundreds in the crowd were weeping uncontrollably.

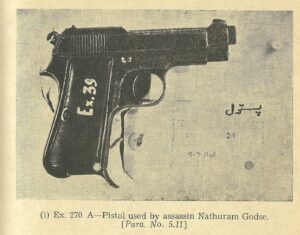

weapon (pistol) used by assassin Godse

Several thousand mourners formed orderly and quite queues at all doors leading to Birla House and for a time they were petmitted to file past the body. Later when it became evident that only a small fraction of the gathering would be able to view Mr Gandhi’s remains tonight, the body was taken to a second floor balcony and placed on a cot tilted under a floodlamp so all in the grounds would see their departed leader.

His head was illuminated by a lamp with five wicks representing the five elements – air, light, water, earth and fire – and also to light his soul, to eternity according to Hindu belief.

Pandit Nehru delivered Mr Gandhi’s valedictory in his radio address late this evening. In a quivering voice he said:

‘Gandhi has gone out of our lives and there is darkness everywhere…The father of our nation is no more – no longer will we run to him for advice and solace…This is a terrible blow to millions and millions in this country…

Our light has gone out, but the light that shone in this country was no ordinary light. For a thousand years that light will be seen in this country and the world will see it…Oh, that this has happened to us! There was so much more to do.’

Referring to the assassin Pandit Nehru said:

‘I can only call him a madman.’

He pleaded for a renewed spirit of peace, which had been Mr Gandhi’s last project, saying:

‘His spirit looks upon us – nothing would displease him more than to see us indulge in violence. All our petty conflicts and difficulties must be ended in the face of this great disaster…In his death he has reminded us of the big things in life.’

Enmity Incurred: Mr Gandhi’s pleas for tolerance since the far-reaching communal warfare of last August and September had earned him th eenmity of extremist elements, notably the Hindu Mahasabha which condemned his fast for inter-religious unity and whose leaders refused to sign his peace pledge. There was also a widespread condemnation of Mr Gandhi’s forgiving attitude among the refugees who had suffered deeply at Moslem hands in the West Punjab.

More serious to India perhaps than loss of Mr Gandhi’s restraining influence on fanatic passions may be the political implications of his death. Though he held no office he was the central figure of India’s dominant Congress party and the last of the ‘old guard’ in the long struggle for liberation from foreign rule.

Some Indian observers were predicting tonight that Mr Gandhi’s death would inevitably be followed by a fission in the Congress party and the emergence of a new political pattern after a period of deep confusion.

Saints and Heroes: Of Truth and Shame

[Anon, Time, Feb 9, 1948; pp. 24-26]

[Note by Sachi: Words in italics and bold fonts, are as in the original.]

For five hours, as Gandhi’s body was pulled through the streets of Delhi, Vallabhbhai Patel crouched on the funeral cart, his head bowed; not once did he raise it. Alongside, barefoot in the dust, walked Jawaharlal Nehru. Said Nehru: “I have a sense of utter shame.”

The shame spread through the world with the news of Gandhi’s murder. The event brought the shock of recognition, rather than the shock of surprise. More forcibly than anyone in his age, Gandhi had asserted that love was the law; how else should he die but through hatred? He had feared machines in the hands of men not wise enough to use them, had warned against the glib, the new, the plausible; how else should he die, but by a pistol in the hands of a young intellectual?

The world knew that it had, in a sense too deep, too simple for the world to understand, connived at his death as it had connived at Lincoln’s. The parallel between Gandhi’s martyrdom and Lincoln’s was close and obvious. Each went down in the hollow between the crest of political victory and the crest of moral defeat. And Gandhi’s ashes were not cold before the world had begun to vulgarize his saintliness (as it had vulgarized Lincoln’s* [Foot note: To this day, Americans will not believe that Lincoln’s achivements were built on consummate skill at political patronage and courthouse politics, just as Gandhi’s were built on shrewd lawyer tricks and diplomatic maneuvering. Charles Francis Adams, great with a sense of historic mission, called on Lincoln before departing for the London legation. Lincoln had little to say of high politics. Adams, being an Adams, never got over the fact that what Lincoln really had on his mind that fateful day was the patronage struggle for the Chicago postmastership.] by insisting, against the facts, that there was no vulgarity in him. The world finds it hard and self-shaming to believe that truth can be glimpsed from the earth; its heroes must be projected into a nebulous world of “mysticism.”

In the little circumstances surrounding Gandhi’s death, in the sordid surroundings of his funeral, there were hints of the real Gandhi, the Gandhi who did not escape reality but pursued it in the teeth of all the windy words like “power” and “progress.”

The story of the death and funeral of Gandhi, however, is best read after a glance south from Delhi, to the place where stands a monument, the Taj Mahal, to another dead Indian. The great Shah Jehan built it to immortalize the memory of his empress’ beauty. It is man’s most eloquent effort to deny that the body and its beauty dies. It is a triumph of the mortician’s art. Some may try to raise a Taj to Gandhi (the prettifiers will scarcely be able to stand statues of that ugly body). But Gandhi’s true monument will be his story—told again & again.

“Let Me Go Now.” On the night before his death, Gandhi had recited a homely Gujarati couplet known in Porbandar (where he was born in 1869). It went:

This is a strange world,

How long have I to play this game?

His last hours were full of this sense of imminence. A few minutes before his assassin shot him down, Gandhi had looked at the tinny dollar watch that dangled from his loincloth. He had been talking with Sardar Patel, Deputy Prime Minister of India. “Let me go now,” said Gandhi. “It’s prayer time for me.”

Then, with his arms round the shoulders of his grandnieces Ava and Manu, the knobby brown man shuffled weakly down the red sandstone pathway leading from Birla House to the vine-covered pergola which served as his prayer-meeting place. Slowly he climbed the three steps leading to the pavilion. A stocky young man in grey slacks, a blue pullover and khaki bush jacket stepped forward and knelt at Gandhi’s feet. He was Nathu Ram Vinayak Godse, editor of the extremist newspaper Hindu Rashtra, which had denounced Gandhi as an appeaser of Moslems. “You are late today for the prayer,” said the murderer. “Yes, I am,” said Gandhi.

Godse suddenly pulled out a tiny Beretta automatic pistol. He fired three times. One bullet ripped into Gandhi’s chest, two into his belly. With hands folded, as if welcoming the blow, in the gesture that is both the Hindu greeting and the Christian attitude of prayer, Gandhi fell backward. He murmured, “Ai Ram, Ai Ram” (O Rama, O Rama), in invocation to the gentle hero of the Hindu pantheon, Gandhi’s favorite.

“Neither Welcoming. . . nor Shrinking.” A sergeant of the Indian Air Force knocked the gun out of Godse’s hands and the yelling crowd bloodied the assassin with blows. The police wrestled him loose and bore him off to jail, where he said: “I am not at all sorry for what I have done. . . ” His two male secretaries carried the bleeding Gandhi into Birla House. He never spoke again. As his soul seeped out, his grandniece Ava chanted Gandhi’s favorite verses from the Hindu holy book Bhagavad-Gita:

“Arjuna asked: ‘My Lord, how can we recognize the saint who has attained pure intellect, who has reached this state of bliss, and whose mind is steady? How does he talk, how does he live, and how does he act?’ “

. . . The sage whose mind is unruffled in suffering, whose desire is not to rouse by enjoyment, who is without attachment to anger or fear—take him to be one who stands at that lofty level.

“He, who wherever he goes, is attached to no person and to no place by ties of flesh; who accepts good and evil alike, neither welcoming the one nor shrinking from the other—take him to be one who is merged in the infinite.”

Soon one of Gandhi’s disciples appeared at the door to Birla House, to speak to the crowd.

“Bapuji [little father] is finished,” he said. Just 28 minutes after he was shot, Gandhi had died.

“Have Your Bath.” A moan went up from the crowd. By the thousands, his followers began to file by the dead man, who was draped in white khadi (homespun cotton) and sprinkled with rose petals. The crush became so great that the body was finally put on a tilted slab on an outside balcony, and bathed in floodlights so that all might see. At the head burned five lamp wicks representing the five elements—air, light, water, earth and fire.

The good friend, disciple and political heir of Gandhi, India’s Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, spoke to the nation on the radio, in quivering voice: “Friends and comrades, the light has gone out of our lives and there is darkness everywhere.”

The nation went into 13-day mourning. In old Delhi a bride and bridegroom about to be married were seated in front of the sacred fire when they heard the news. They postponed the wedding and returned to their respective homes. A milkman emptied his buckets of milk on the street, crying: “Bapuji is no more. What’s the use of selling milk now?”

The All-India radio broadcast Gandhi’s favorites: extracts from the Gita, the Upanishads and the Koran; the Lord’s Prayer; the Christian hymn, When I Survey the Wondrous Cross. Then, after midnight, Gandhi’s youngest son Devadas (who insisted that Gandhi be cremated, as he had wished) helped wash the body. He and Gandhi’s secretary Pyarelal then wrapped the body in pure white khadi. They put a yellow paste of sandalwood and water on his face.

The household chanted their leader’s favorite Hindu song: “Dress yourself in rich attire, befitting the occasion, because you are now to go to your beloved’s haven. You will have to lie on the bare earth, cover yourself with dust and ultimately become one with the dust. Have your bath and dress properly. Remember you are not to come back from where you are going.”

The vehicle selected to bear this man of nonviolence on his last journey was a weapons carrier. Those in charge of the arrangements, recalling Gandhi’s opposition to machines, did not let the weapons carrier’s motor propel it; men with ropes dragged it through New Delhi’s streets. The men were soldiers, and soldiers headed the cortege. Police, about whom Gandhi also had had his doubts, lined the streets. Overhead, military airplanes, built to drop bombs on people Gandhi loved, dropped rose petals on Gandhi’s bier. Tanks and armored cars rumbled behind, as if to make it very clear that the world had said: “You are dead and I will not die and, though you have made me feel uneasy, I have not listened to what you have been trying to tell me.”

In front of the bier marched Gandhi’s third and fourth sons, Ramdas and Devadas,*

[Foot note: Gandhi, like Lincoln, had his family sorrows. His first son Hiralal, who drinks, was estranged from Gandhi, was once a convert to Islam. Last week second son Manilal was in Durban, South Africa.] barefoot. It took almost five hours for the marchers to cover the six miles to the banks of the sacred river, Jumna. The surging crowd, which sometimes threatened to engulf the funeral procession, threw rose petals at the bier, shouted “Mahatma Gandhi ki jai!”—”Victory to Great Soul Gandhi!”

At the river bank the procession came to a field as different as possible from the glittering Taj Mahal. This field looked like a junkyard. Here & there water buffalo were grazing. The Department of Public Works had built overnight a square platform of brick and cement, three feet high and twelve feet square. At the four corners were stumps of the sacred peepul tree. On the platform was half a ton of sandalwood, mixed with ghi (melted butter), incense, coconuts and camphor. Gandhi’s body was raised to the pyre.

As Gandhi’s sons gently laid more sandalwood atop the corpse, the throng pressed wildly in. Screaming men tried to get close enough to place a stick of sandalwood on the pyre. Hysterical women clamored for one last look; some tried to throw themselves on the pyre. Soldiers and police had to beat the crowd back with lathis (police sticks), just as they had beaten Gandhi’s nonviolent followers in scores of demonstrations.

Son Ramdas set fire to the ghi-soaked wood with the charcoal he had carried, smoldering, all the way from Birla House. Nehru, Patel, Governor General Earl Mountbatten and his Lady threw last rose petals on the pyre as the white smoke of sweet-smelling sandalwood rose against the scarlet evening sun. From nearly a million throats came the chant, half in mourning, half in triumph: “Mahatma Gandhi amar ho gae!”—”Mahatma Gandhi has become immortal!”

“Is He Really Great?” When Mahatma Gandhi was in London in 1931 to plead for Indian independence, a small girl started to ask for his autograph. Then she drew back shyly before the strange little dhoti-clad man with a cavernous mouth, jutting ears and scrawny neck. She looked up at her mother and asked: “Mummy, is he really great?”

Last week the answer from all continents was a fatuous yes. The answer missed the point; Gandhi was a rarer human being—a good man. He disturbed people by his goodness. He called himself “a Hindu of Hindus,” and yet he put many a professing Christian to shame. “The spirit of the Sermon on the Mount,” wrote the man who fitted the rubrics of the Beatitudes more comfortably than most Christians, “competes almost on equal terms with the Bhagavad-Gita for the domination of my heart.”

“I Heartily Detest. . . .” From the Russian pacifist Count Leo Tolstoy and the American hermit-naturalist Henry David Thoreau, Gandhi learned the doctrines of nonviolence and deliberate, organized disobedience to unjust power. He said it was better to be poor and secure with a home spinning wheel than to be less poor and frightened with a great steel mill. He combined the elements into a belief of Christlike simplicity: oppose hate with love, greed with openhandedness, lust with self-control; harm no feeling creature. Of material progress, he said: “I heartily detest this mad desire to destroy distance and time.”

The house where Gandhi died belonged to Ghanshyam Das Birla, owner of some of the largest textile mills in the world. Gandhi, who hated Birla’s mills, loved Birla, whose devotion to Gandhi did not reach to Gandhi’s anti-industrial ideas.

“Where We Have the Weapons. . .” Satyagraha (soulforce, or conquering through love) was the name Gandhi gave to mass nonviolent resistance. Potently he applied satyagraha against the British Raj. “The British,” he wrote, “want us to put the struggle on the plane of machine guns. They have weapons and we have not. Our only assurance of beating them is to keep it on the plane where we have the weapons and they have not.”

Yet Gandhi’s weapon contained a measurable threat of violence in India. When Gandhi fasted, Britons sometimes dared not keep him in jail, lest a massive anger at his death in their hands engulf India. “I always get my best bargains behind prison bars,” he once chuckled. When Gandhi fasted, Moslem, Hindu and Untouchable leaders had to promise to work better together, lest that anger of the masses be directed against them. No communal group, not the mighty British Raj itself, dared have Gandhi’s blood on its hands.

“If We Could Spit . . .” With independence, Gandhi’s great victory, came defeat. India, seething with fear and fanaticism, spurted blood in scores of riots. Mohamed Ali Jinnah, once a member of Gandhi’s All-India Congress Party, bolted, saying that the Congress was an instrument to impose Hindu rule on India’s Moslem minority. With a notably unmystical metaphor, Gandhi said: “If we Indians could only spit in unison, we would form a puddle big enough to drown 300,000 Englishmen.” But Jinnah refused to spit in unison with Hindus, for any cause. He demanded, and got, his separate Moslem state of Pakistan.

Lone Voice. Independence without unity was as ashes in Gandhi’s mouth. He continued to work for the reunion of Pakistan with India. But in the last half year of his life Gandhi found not only the Moslem leader, but many of his own Hindus, opposing attempts at reconciliation. Orthodox Hindus resented his inroads on Hindu customs which Gandhi considered brutal, and therefore indefensible: untouchability, suttee (widow suicide), child marriages. Hindu and Sikh refugees from Moslem hate and murder, pouring into Delhi and other Indian cities, clamored for revenge. The militant Hindu organization Mahasabha (Great Society), to which Gandhi’s assassin belonged, worked to make India purely Hindu state. Patel gave some encouragement to the extremists, which may partly explain why, at Gandhi’s funeral, his head was bowed.

Hindus, not Moslems, stoned Gandhi’s house when he went to Calcutta to encourage communal peace last August. On his 78th birthday, Oct. 2, Gandhi spoke sadly: “Why do I receive all these congratulations? . . . The time was when whatever I said, the masses followed. But today I am a lone voice in India.” In November, a TIME correspondent went to see him. Gandhi said: “Can you squat?” The reporter squatted. Gandhi at one point in the interview said: “Three hundred years is as nothing.” He returned to the present: “The fear haunts me that India must yet go through a deeper blood bath.” The government which he had dominated came closer & closer to open war on Pakistan. Only Gandhi’s fast last month checked the drift toward open hostilities over Kashmir State.

Violence broke out in India anew after Gandhi’s death. Fifty were reported killed as-Gandhi admirers exacted a blood price from the Mahasabha extremists. Some dared to hope that Gandhi’s injunction to abhor violence might take on added force from his martyrdom.

The hope was slim. In his lifetime his fellow men had sensed that Gandhi had a great message; of what the message was, they had scarcely an inkling. Gandhi, by the manner of his death, told them a little more of what he had been trying to communicate—but not enough to make them live as he had tried to. The world which revered few men had revered him—but not enough to follow where he pointed. The world was ashamed, and bewildered. Premier Nehru, that great and learned and most fluent man, came back to Gandhi’s cooling pyre the day after the cremation. He spoke a few halting, wistful sentences, like a lost child. Said Nehru:

“Bapuji, here are flowers. Today, at least, I can offer them to your bones and ashes. Where will I offer them tomorrow, and to whom?”

*****

Pre-Assassination calendar of events in Jan 1948, when Gandhi was staying in Delhi at Birla’s House and held prayer meetings daily in the evening.

Jan 12 – As per negotiation, India had to pay a sum of 550 million (55 crores) rupees to Pakistan. But the Indian government was reluctant to pay this sum, for fear that Pakistan may use this sum to purchase arms for use against India in Kashmir. The Home Minister Sardar Patel had made a statement. Gandhi strongly opposed this decision. His view was, this was a breach of faith in the negotiation made. Thus he declared his intention to fast for an indefinite period, on the pretext of improving communal relations in the capital.

Jan 13 – Gandhi’s fast started. Decision to ‘hit’ Gandhi was taken by the conspirators, for his ‘unreasonable demand on forcing’ the Indian government to pay the large sum of money to Pakistan.

Jan 14 – fast continued. [Hearing cries ‘Let Gandhi die; we will have revenge by blood for blood’ Jawaharlal Nehru rushed out and challenged ‘Who says let Gandhi die? Come, first kill me.’ According to one biographer, Gandhi lost 2 pounds (0.9 kg), and his body weight decreased to 109 pounds (49.4 kg). ‘His kidneys were also failing to eliminate the water he drank.’ Gopal Godse (assassin Nathuram Godse’s younger brother, employed as a store keeping in an army depot, near Poona) had submitted a request for 7 days leave, beginning from Jan 15th. This was refused for the reason that he had to appear before a Board of Officers on Jan 16th.

Jan 15 – fast continued. Gandhi delivered post prayer speech on mike from his room.

Jan 16 – fast continued. Gandhi had quipped ‘I do not wish to live if peace is not established in India and Pakistan’. Gopal Godse applied again for a week of leave, from Jan 17th and this request was granted. On request from his brother (assassin Nathuram), Gopal had brought a revolver which he had with him.

Jan 17 – fast continued. Gandhi’s health condition was causing anxiety. Nathuram Godse and Narayan Apte had travelled to Delhi and stayed till 20th, at Marina Hotel, after registering themselves under false names. Vishnu Karkare and Madanlal Pahwa also went to Delhi, and stayed at Sharif Hotel, under assumed names.

Jan 18 – Indian government ‘surrendered’ to Gandhi’s demand; on receiving assurance from all communities, Gandhi broke fast by having juice, given by Maulana Azad. Gopal Godse reached Delhi, in the evening. They had assembled 2 revolvers, gun-cotton slabs and several hand grenades. Badge (who later turned to be a prosecution witness, and implicated other co-conspirators) was the guy who had provided the 2nd revolver and supplied gun cotton slabs and hand grenades.

Jan 19 – Seven conspirators charged with assassination (namely Nathuram Godse, Apte, Karkare, Pahwa, Shankar Kistaiyya, Gopal Godse, and Digambar Badge) had arrived in Delhi, by the evening. Kistayya was an illiterate from Andhra Pradesh who worked as a trusted servant in Badge’s house.

Jan 20 – In the morning, Apte, Karkare, Kistaiyya and Badge paid a reconnaissance visit to Birla House. A bomb exploded in the compound, when Gandhi was holding prayer. This was his first public appearance after 12th, when he began his fast. The plan of the conspirators was as follows: During the prayer meeting, (1) Badge was to shoot Gandhi from behind and follow up by throwing a hand grenade. (2) Kistaiyya was to duplicate the act from the front by shooting and throwing a hand grenade. (3) Pahwa was to explode a gun-cotton slab, near the back gate of the house, to distract attention of the crowd gathered. Pahwa was a Punjabi Hindu refugee from newly formed Pakistan, who had witnessed the murders of his father and aunt by a Muslim mob, before he left Pakistan. The plan of conspirators went awry, when Badge’s courage failed him. Only, Pahwa accomplished task, and he was caught and handed to the police.

Jan 26 – Gandhi had a 30 min. talk with judge Gopal Das Khosla (who subsequently served as one of the three High Court judges, in the Gandhi assassination trials appeal in 1949). Pahwa’s arrest made the other conspirators to quickly complete the task they had in plan, because they feared that Pahwa may ‘spill the beans’ when subjected to interrogation and they could be taken into custody.

Jan 27 – Gandhi wrote ‘Congress Position’ (published posthumously in Harijan, Feb 1, 1948), suggesting that Congress should cease as political body and should devote to people’s service. Nathuram Godse and Apte arrived at Delhi by plane at 12:40 pm. Same afternoon they left for Gwalior by train at 10:38 pm and stayed with Dr. Parchure. The objective was to purchase a pistol that can fire accurately. This objective was fulfilled.

Jan 29 – Gandhi drafted the constitution for Congress service militia (published posthumously in Harijan, Feb 15, 1948), as outlined in ‘Congress Position’ of 27th. Nathuram Godse and Apte returned to Delhi in the morning. Karkare also had arrived in Delhi. As a diversion, Karkare and Apte went to see a movie at night. But, Nathuram Godse wished to rest, and spent time reading a book.

Jan 30 – Nathuram Godse, Apte and Karkare went to a thick forest and Godse checked that pistol was in working condition by firing a few rounds. Godse was satisfied. Around 4:30 pm, Gandhi was visited by Sardar Patel and both discussed the rift between Nehru and Patel intensely, to the extent that Gandhi was held late for his scheduled prayer meeting at 5:00. At 4:30 pm, Godse left first to Birla House. Apte and Karkare followed him a few minutes later. Gandhi was assassinated around quarter past five (17:15 hr, Indian standard time), while on his way to evening prayer ground at Birla House, by Nathuram Vinayak Godse. Gandhi collapsed with the words ‘Hai Ram’.

Post-Assassination Calendar of Events in 1948 and 1949

Jan 30 – assassin Nathuram Godse was apprehended immediately, after his act.

Jan 31 – Badge was taken into custody.

Feb 5 – Gopal Godse was taken into custody. Dr. Parchure was apprehended in Gwalior.

Feb 6 – Kistaiyya was arrested.

Feb 14 – Apte and Karkare were arrested.

May 27 – Twelve individuals were accused under 11 different charges of the Indian Penal Court and the Indian Arms Act 1878. Among these, three were absconding. Nine producd before a Special Court under a single judge Atmacharan Agrawal (a senior member of the judicial branch of the Indian Civil Service) were: (1) Nathuram Vinayak Godse, (2) Narayan Dattatraya Apte, (3) Vishnu Ramkrishna Karkare, (4) Madanlal K Pahwa, (5) Shankar Kistaiya, (6) Gopal Vinayak Godse, (7) Digambar Ramchandra Badge, (8) Vinayak Damodar Savarkar and (9) Dattatraya Sadashiv Parchure. Three absconders were, Gangadhar Dandavate, Gangadhar Jadhao and Suryadeo Sharma.

Jun 22 – Assassination trial commenced before Atmacharan. Among the 9 accused mentioned above, accused no. 7 Badge (name pronounced as Bahdgay) – a co-conspirator became a prosecution witness and incriminated his accomplices. As such, 8 individuals were charged with murder, conspiracy to commit murder and offences punishable under the Arms Act and the Explosive Substances Act. They were,

Accused 1: Nathuram Vinayak Godse, aged 37, editor of Hindu Rashtra, from Poona.

Accused 2: Narayan Dattatraya Apte, aged 34, managing editor of Hindu Rashtra, from Poona.

Accused 3: Vishnu Ramkrishna Karkare, 37, restaurant proprietor, Ahmednagar.

Accused 4: Madanlal K. Pahwa, 20, a refugee from Montgomery, Pakistan – in refugee camp, Ahmednagar.

Accused 5: Shankar Kistayya, 20, domestic servant of Digambar Ramchandra Badge, Poona.

Accused 6: Gopal Vinayak Godse, 27, storekeeper, Army depot, Poona.

Accused 7: Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, 65, barrister at law, Bombay.

Accused 8: Dattatraya Parchure, 49, medical practitioner, Gwalior.

June 24 – Examination of witnesses began. A total of 149 witnesses were called.

Sept 11 – Mohammed Ali Jinnah, Gandhi’s political foe who adamantly split Pakistan from greater India, died of tuberculosis in Karachi.

Nov 6 – Examination of witnesses concluded.

Dec 30 – Hearing closed.

Feb 10, 1949 – Judgment delivered by judge Atmacharan. Among those charged, Accused 7 was acquitted.

Accused 1 and 2 were sentenced to death. Accused 3, 4, 5, 6 and 8 were awarded life sentences. Digambar Badge received pardon and set free for his depositions against co-conspirators.

Feb 14, 1949 – Appeals were filed by seven convicted individuals in the Punjab High Court.

May 2, 1949 – Hearing began, in front of a bench of three judges – Justice A.N. Bhandari, Justice Achhruram and Justice G.D. Khosla, and continued till June.

June 22, 1949 – Appeal judgement delivered. Among the seven convicted individuals, Kistaiya and Dr. Parchure were found not guilty and were acquitted. Life sentences of Vishnu Karkare, Gopal Godse and Pahwa were confirmed. Death sentences of Nathuram Godse and Narayan Apte were also confirmed. Upon the acquittal of Dr. Parchure, absconding three accused were also set free, after they appeared before a magistrate in Gwalior.

Nov 15, 1949 – Nathuram Godse and Narayan Apte were executed at 8 am in Ambala jail in Punjab.

Oct 13, 1964 – Vishnu Karkare, Gopal Godse and Madanlal Pahwa were released free, after 16 years in prison. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru had died four months before in May.

Sources

C.C. Dalal: Gandhi: 1915-1948 – a detailed chronology, Gandhi Peace Foundation, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Bombay, 1971.

Erik H. Erikson: Gandhi’s Truth – On the Origin of militant nonviolence, W. Norton & Co, New York, 1969.

Gopal Godse: ‘May it Please Your Honour – Nathuram Godse’, 3rd ed., Surya Prakashan, Delhi, 1987.

Martin Green: Gandhi – Voice of a New Age Revolution, Continuum Publishing Co, New York, 1993.

Ramachandra Guha: Gandhi – The Years that changed the world 1914-1948, Penguin Books, London, 2018.

G.D. Khosla: The Murder of the Mahatma and Other Cases from a Judge’s Notebook, Chatto & Windus, London, 1963.

William L. Shirer: Gandhi – a memoir, Pocket Books, New York, 1979.