Indira’s Chikmagalur and Thanjavur Imbroglio

by Sachi Sri Kantha, November 4, 2024

Chronological record of political activities by Indira Gandhi MGR Karunanadhi 1977-1979

Fellow MGR biographer R. Kannan’s thoughts about the contents in Part 77 of this series (received on Sept 14), were as follows:

“ I enjoyed reading part 77 of the MGR series, which nicely transported me to the Janata years—a period bungled by India’s aged leadership that paved the way for Indira Gandhi’s return. You have, as always, skillfully employed the Time and Dan Rather interviews, not to mention the cartoons, to highlight Desai’s idiosyncrasy. The Econmic & Political Weekly report on the black flag demonstration was new to me.”!

‘High time we did something about it. The party is splitting rather rapidly! Each of them is the leader of a splinter group!” R.K. Luxman’s general cartoon about Indian political parties

My response to Kannan’s thoughts was as follows:

“Thanks. It has been relatively easy for me to write about MGR’s cinema life related chapters; but as for his political phase – new authentic materials are hard to come by, and somehow I manage with what I could collect in the net archives from reliable sources.”

Further thoughts on Morarji Desai’s auto-urine therapy

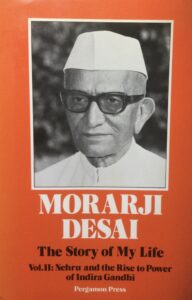

After submission of my previous chapter, I was more curious to dig a little deeper into Morarji Desai’s promotion of auto-urine therapy, which made international news during 1977-78. One may call it, a scientist’s curiosity. While web surfing for old books in the Net, I was able to locate a vendor who sold Morarji’s autobiography ‘The Story of My Life’ (in 2 volumes). I opted to purchase vol. II; it’s subtitle read ‘Nehru and the Rise to Power of Indira Gandhi’. This volume consists of 48 chapters, and Morarji had stopped the autobiography in November 1969, with the split in the Congress Party, forced by Indira. Final three chapters (46 to 48) offered personal details – My Family (chapter 46), Experiences of Illness (chapter 47) and My Faith (chapter 48).

As the published date of the book was 1979, events of 1970s including his tenure as the prime minister (1977-1979) were NOT covered. Curiously, in Chapter 47, that provided particular details about his illnesses (until 1969), Morarji had omitted any mention of details about his ‘auto-urine therapy’, such as when it started and for how long he continued etc. One is not sure, whether he had self-censored himself anticipating negative media publicity, or the publishing editors had pruned the original text provided by Morarji.

Now, I provide below email communications I had with my younger Indian collaborator and pal of over 25 years, Dr Sanjay A. Pai. He is a pathologist, currently in Bengaluru, Karnataka.

“Sanjay, I have a query, which you can answer for me. I have been reading Morarji Desai’s autobiography – vol. 2. One chapter, he had included towards the end was ‘Experiences of Illness’. In it, he describes that he suffered from pilitis in 1949 and 1955. What is it? The common English dictionaries I checked, and even medical dictionaries (Dorland’s and Stedman’s) DONT have any descriptions for pilitis.

Morarji Desai Autobiography vol. 2 (1979)

I wonder, it is related pyelitis – inflammation of renal pelvis. Even Medline, doesn’t provide a single entry for this term. Do you have any clue?” (Nov. 3)

Dr. Pai’s response “Hi Sachi, Pilitis – there is no such term. Either it is pyelitis as you point out – or maybe piles?” (Nov. 3)

My response, providing excerpts from Morarji’s descriptions, was as follows

“Thanks for your quick response, and confirmation about this word ‘pilitis’ which Morarji had used. I also thought of piles as well. In fact, he had used it twice, in the same chapter. So, it couldn’t have been a typo or printer’s error. Just for your info, I provide the sentences below/

“When the Bombay Government was in Poona in the monsoon of 1949, suddenly one morning I got an attack of pilitis. As I believed in nature cure, I refused to take allopathic medicines and fasted to cure myself. I was getting high fever and was bedridden. My colleagues, doctors and friends were pressing me for taking allopathic medicines….

Then, in the next page, Morarji had written, “I got another attack of pilitis in the beginning of December 1955. This was a more serious attack than the earlier one and my fever went up to 104oF. At the time of the first attack I had taken antibiotic tablets under pressure, but this time I stuck to my determination not to have any medicine and took only nature cure treatment…..

Few paragraphs later, Morarji writes, “I realised as late as 1958 that the pain which I suffered from in 1949, 1951 and 1955 was due to a kidney stone…..”

So, I guess, is description is of pyelitis – and not piles.

I could infer that he suffered from kidney stone problem since 1949. He had an operation for it in Dec 1958. Then, he mentions that he was operated for hernia in July 1964, as well as vasectomy operation, prior to hernia operation.” (Nov.3)

Dr. Pai’s confirmation followed: “Fever and kidney stones suggests that it’s pyelitis all right.”(Nov. 3)

Thus, my inference gained from the details available from his autobiography, Morarji Desai had suffered from kidney-related afflictions for long time since his early 50s. Thus, his promotion of auto-urine therapy in words and deeds have to be linked to this medical fact, and his personal preferences of believing in ‘nature cure’ and fasting. Morarji also mentions that his younger brother Nanubhai Desai was also a surgeon.

Indira Gandhi and MGR

Janata Party’s first mis-step of making Indira a Martyr

Main political events from 1977 to 1979, experienced by Indira Gandhi, MGR and Karunanidhi, have been summarized in a table. PDF format of this table is given above. Within 7 months of holding power, Morarji-led Janata Party had begun losing its focus and popularity due to multiple mis-steps, and in-fighting among the three top leaders. R.K. Luxman’s cartoon poked fun on such party infighting. This cartoon’s caption, voiced by an observer was: ‘High time, we did something about it. The party is splitting rather rapidly! Each one of them is the leader of a splinter group!’

The first misstep was the bungled arrest of Indira Gandhi on Oct 3, 1977. Two paragraphs from the Newsweek magazine’s cover-story are excerpted below:

“It was the beginning of a journey that the CBI [Central Bureau of Investigation] officers – and the seven-month old government of Morarji Desai – probably wished in retrospect they had never embarked upon. When the car carrying Mrs Gandhi stopped at a railroad crossing on the way to its destination, a rest house in a neigbouring state, the former Prime Minsiter jumped out and sat down on a culvert at the side of the road, refusing to go any further until her captors produced the special order needed to take a person in custody across a state line. Sheepishly, the CBI officers had to turn bac with their prisoner – in their haste, they had forgotten to get the order. Mrs Gandhi ended up spending the night in an officers’ barracks in New Delhi, and on the following day the government suffered a far more serious humiliation: as supporters and opponents of Mrs Gandhi battled police and each other outside the crowded courtroom, Delhi metropolitan magistrate Ripusudan Dayal ruled that no evidence had been produced to bac up the corruption charges against Mrs Gandhi and released her from detention.”

“The government’s fortunes have been on the wane for quite some time, with critics of Desai charging that after spending his entire life fighting to be Prime Minister he has now run out of momentum because he has achieved his ultimate goal. While [Charan] Singh has shouldered most of the blame for last week’s foul-up, Desai also came in for heavy criticism since he had repeatedly assured the country that Mrs Gandhi would only be arrested if the government had indisputable evidence that she had committed serious criminal acts. And recently the puritanical Indian leader has tended to ignore the harsh realities of political life – growing popular disaffection because of rising prices and even the increasingly vocal pro-Gandhi demonstrators in front of his house – while pressing on single-mindedly with his campaign to have liquor banned throughout India, lecturing ceaselessly about the evils of drink and occasionally delivering little homilies on the value of drinking one’s own urine.”

My inferences were: (1) This particular arrest experience made Indira to protect herself (as well as her son Sanjay), and her political image to gain a MP status from a parliamentary constituency, at the earliest. (2) Thinking that it’s too premature to test her political strength in any of the Northern states where her Congress Party was resoundingly defeated in the March 1977 polls, Indira looked towards the South, where her party fared better on its own (in Karnataka), or in alliance with MGR (in Tamil Nadu).

Chikmagalur (Karnataka) by-election of Nov 7, 1978

As her biographer Inder Malhotra had observed, in early 1978,

“Indira was travelling in Karnataka, visiting temples and monasteries, and finally settling down in a lovely rest house in the hills of Mercara to do some writing and to indulge in her passion of walking barefoot in the mountains or on the seashore. It was in these sylvan surroundings that she got word that Sanjay was in deep trouble.

….The Supreme Court decided on May 5th 1978, that Sanjay be placed in ‘judicial custody for a month’…By the time Sanjay came out of jail,…Indira had made up her mind to overcome an irritating political disability by re-entering Parliament.”

The dictionary definition of ‘imbroglio’ states, ‘confused heap; confused or complicated (esp. political or dramatic) situation’. In a ‘quickie paper’ published in the Indian Journal of Political Science of March 1979, on Chikmagalur by-election of 1978, authors Rajasekhariah and Jangam had recorded the this imbroglio as follows:

“In the (March) 1977 elections, the Congress candidate Mr [D.B.]Chandre Gowda, a local Vokkaliga, got elected with a majority of around 60,000 votes. When the Congress split in [January] 1978, Mr Gowda remained with Indira Gandhi’s faction (Congress-I). Subsequently, in what was supposed to be a carefully concealed political manoeuvre, the Karnatak Chief Minister, Devraj Urs, and some of his colleagues close to Indira Gandhi, manoeuvred to get the Chikmagalur seat vacated and Indira Gandhi installed as a Congress-I candidate for the byelection. There is some controversy about the choice of this electorate for her. One the one hand it has been claimed that this was chosen as a safe constituency, on the other hand, it has also been maintained that Devaraj Urs deliberately got this constituency fixed up in the remote hope that Indira Gandhi might lose, in which case a political liability would have been conveniently liquidated. There is also a third view that Urs advised Indira Gandhi against the constituency and it was the anti-Urs pro-Indira caucus in the Congress-I in Karnataka that advised her to stand for the by-election from this constituency. Whatever may the truth be, it is clear that Indira Gandhi took the decision on her own.”

The imbroglio faced by Indira in the Chikmagalur by-election (held on Nov 7, 1978) which she contested was within her own party. There was NO interference from Morarji Desai. But, the imbroglio that Indira faced in the Thanjavur by-election that was on schedule to held in 1979 was of a different sort for two specific reasons: (1) Indira had to depend on MGR’s support for her victory, because her Congress (I) party alone couldn’t assure her victory, if pitted against DMK leader Karunanidhi; (2) Morarji Desai’s influence via MGR was openly visible. More on this later.

Continuing the Chikmagalur story, Indira’s tormentor in the Janata Party Charan Singh had resigned from Morarji’s Cabinet on July 1, 1978 due to differences between them over prosecuting Indira about her abuse of power during the Emergency Period. While MGR campaigned for Indira and offered considerable financial assistance for the campaign, Karunanidhi supported Janata Party candidate Veerendra Patil. Karunanidhi’s autobiography provides following details;

“Indira submitted her nomination papers on Oct 6, 1978. Veerendra Patil visited Chennai to meet me and solicited support from DMK, for his candidacy. Decision to support Veerendra Patil was made by the party’s executive committee on Oct 14, 1978. Apart from Veerendra Patil, even the Janata Party’s chief campaign manager George Fernandes also sent a letter soliciting support for Janata Party. Approximately 85,000 voters in Chikmagalur constituency were Tamils then…At the request of Ramakrishna Hegde, I attended and spoke at the campaign meeting for Janata Party candidate on November 2, 1978. It was presided by old war horse Nijalingappa. Acharya Kripalani, Veerendra Patil, Marxist Communist Party leader B.T. Ranadive, George Fernandes also spoke at that meeting.”

Karunanidhi also contributed the following sentiments.

“After Janata Party came to power, for whatever reason, it had neglected DMK which had worked for the success of Janata. If this be the case, why should DMK support Janata candidate at the Chikmagalur election? This concern prevailed not only among DMK supporters, but also those who were unaffiliated to any party. At the Chikmagalur campaign meeting, I provided my explanation. It was this:

‘After Janata Party gained power, many expected relief to Tamil Nadu, akin to what was offered in other states of India. But, for some reason, Janata leaders residing at New Delhi never focused their eyes at Tamil Nadu. I’m not angry for this sort of small mindedness. I’m not prepared to show my anger at the leaders, at a time like this. Some may have anger at the temple priest; due to this, devotees will never get angry with the God. Akin to this, we have anger against the Janata leaders. But, despite this anger, we will never forego praying the God of democracy. It is for this reason, we decided to support Janata Party to protect democracy.’…

Due to heavy rains, on the polling day registered votes were relatively low. In the afternoon, quite many polling booths were empty. There were riots in many locations. Eventually, Indira Gandhi won the election, with a margin of 67,000 votes…”

Karunanidhi continued further: “When UNI reported asked my view on the results, my response was: ‘Due to her victory at Chikmagalur by-election, Opposition had received a recognized leader, Even though, ruling party and the Opposition do differ in their policies, to protect democracy in India, its my wish and request that they work together to retain the rights of citizens.”

Commenting on the results of Chikmagalur, Indira’s biographer Katherine Frank’s inference was: ‘It was an ideal constituency for her [Indira]: 50 percent of the voters were women; 45 percent belonged to scheduled or backward castes or minorities and nearly half of the population lived below the poverty line. Chikmagalur was also a Congress stronghold…. Everyone expected [Veerendra] Patil to win. But the crowds that came to hear Indira were enthusiastic, even reverential, and they far outnumbered those who came to see Patil and Fernandes. It was Mother Indira all over again. Despite press predictions, Indira won by a large margin of 70,000 votes.’

But, due to the shenanigans of the Janata Party leaders, Indira was expelled from Lok Sabha in December 1978, after being charged for a serious breach of privilege and contempt of the House. She was arrested and held in Tihar jail for a week, and released on December 26 1978. A wily tactician that she was, Indira played her cards with the classic ‘Divide and Rule’ strategy. On December 23, 1978, Charan Singh (then out-of Morarji Cabinet) held a vast rally to show his strength; through an intermediary, Indira sent flowers to Charan Singh, and opened ‘a line communication’ with her prime tormentor in the parliament.

Though Indira was pushed out of the Lok Sabha by a devious strategy adopted by Janata Party hierarchy, still she entertained hopes of re-entering via another by-election, while inducing the split between Morarji Desai and Charan Singh. A prominent reason for her interest in a parliamentary seat, was the protective layer of immunity it offered as a Lok Sabha MP. A secondary one was, rather than being dependent on a senior party member (who might be tempted to betray her) to function as the leader of her Congress (I) party in her absence, she herself can hold in leash of MPs belonging to her party.

Thanjavur (Tamil Nadu) by-election imbroglio of 1979

When the by-election for Thanjavur constituency was announced to held in June 1979, Indira was either tempted or pushed forward (by her party’s Tamil Nadu leaders like G.K. Moopanar, R.V. Swaminathan and R. Venkataraman) to enter the race. Please check the time-line for dates in May 1979, in the provided Table, for detail. But, she badly needed MGR’s assurance/clearance before-hand. A simplistic view that MGR backed out at the last minute in supporting Indira, after being threatened by Morarji Desai was promoted heavily by anti-MGR press and amplified by DMK propagandists, including Karunanidhi. There was also an announcement from DMK – in a scenario where Indira enters the ring as a Congress (I) party candidate for Thanjavur by-election scheduled for June 17, 1979, Karunanidhi himself will contest as a DMK candidate against her. This was also included by Karunanidhi in his autobiography, indirectly as a headline news item appearing in English evening paper ‘Mail’. Furthermore, Karunanidhi had also trumpeted his ‘I told you so’ on MGR’s fence-sitting behavior at a conference he had attended and spoke on May 6, 1979. It was this: ‘Though ADMK had stated that it will support Congress (I) party, in a situation when Premier Desai calls the ADMK leadership and threatens, they will abandon Indira Gandhi. Therefore, Indira Gandhi should not trust ADMK.’

However, the development of this imbroglio turned out to be more foggy and complex. An unsigned commentary, which appeared in the Economic and Political Weekly of May 26, 1979 sheds more light. It was captioned – ‘Congress (I) – Downhill All the Way?’ All except the last paragraph is reproduced below:

“That Indira Gandhi had to go in search of a constituency from which she could seek election to the Lok Sabha was a comedown enough for her; that she was prepared to face the far from certain prospects of victory at Thanjavur only underline her desperation: and the last minute reversal of the decision imposed upon her is a humiliation she could have well done without.

The developments in Thanjavur have once again shown that in sharp contrast to her earlier style of functioning, when she was the grand manipulator and others served her purposes, she is now herself being used by her own avowedly loyal followers and admirers. Indeed, as her immediate political future was being decided by Devaraj Urs, M G Ramachandran and even Morarji Desai, Indira Gandhi herself was forced to be a mere observer on the sidelines.

What is, however, relevant about the Thanjavur drama is not whether any pressures were brought upon by the Prime Minister [Morarji] on the Tamil Nadu chief minister [MGR] not to extend support to Indira Gandhi with barely concealed threats being held in the event of his disregarding the Centre’s ‘advice’, or whether the Karnataka chief minister [Urs] played his by now well known ambiguous role by both supporting and opposing Indira Gandhi in the same breath, or even whether the Tamil Nadu chief minister was moved by no other consideration except that of ensuring that Thanjavur did not become a battlefield where political battles of an entirely different sort would be engaged upon by proxy; far more to the point is the fact that in the space of barely a few hours on the night of Sunday, May 20, Indira Gandhi was made to change her mind. So, once again, the plans to return to Parliament have gone awry; and very graciously, Devaraj Urs has repeated that Chikmagalur is available to her ‘for the asking’.

Indira Gandhi’s chagrin at being (for a change) so neatly made use of has been barely concealed. She has flatly repudiated the Tamil Nadu chief minister’s contention that his lack of enthusiasm for her candidacy at Thanjavur was due to apprehensions that such entry would raise law and order problems; and while reiterating that her preference for a constituency from which she could enter Parliament was ‘always Chikmagalur’ ( a scarcely credible claim is that every preparation had been made to begin her election campaign in the Thanjavur), she has also expressed her annoyance and even apprehensions about the Karnataka chief minister. She was probably speaking nothing but the whole truth when, in answer to a question from a correspondent at Madras airport on Wednesday whether Karnataka chief minister had anything to do with the Tamil Nadu chief minister’s decision, she said ‘I do not know’.

The poor response to the rally against the special courts bill ought to have convinced her that even within her own party, there is little enthusiasm to fight her personal battles…”

Karunanidhi’s version

Though overtly biased against MGR, for details on Indira’s decision not to contest Thanjavur by-election, I have to depend on Karunanidhi’s version, as he had written in his autobiography. He had provided details on what happened on which dates of May 1979. Excerpts, in translation:

“May 12, 1979: ADMK committee announced that they will support the candidacy of Congress (I) candidate at Thanjavur by-election, despite mentioning that they had won the constituency in the previous election, and presumptively it should be their chance.

News came that Indira Gandhi had decided to contest Thanjavur election and she will arrive at Thanjavur on May 21, 1979. Congress Party supporters decorated the walls with the Hand symbol.

May 15, 1979: Chief Minister MGR talking to the reporters said, whether Indira Gandhi contests the election or not, ADMK will support Congress (I) candidacy; it should not mean that he dislikes Janata rule.

May 20, 1979: All the national newspapers reported that Indira Gandhi contesting Thanjavur by-election had been confirmed. The decision was made after MGR and Congress (I) leader Moopanar had met and talked with Indira Gandhi. It was also announced that details on where will Indira Gandhi stay and how the propaganda will be conducted had been decided.

May 21, 1979: Newspaper reports stated the opposite. Indira Gandhi will not contest Thanjavur by-election. Her party’s parliamentary committee had made such decision, and Indira Gandhi’s visit to Thanjavur had been cancelled.

Congress (I) party’s Tamil Nadu leader R.V. Swaminathan announced that due to last minute position change by ADAMK, the decision of not having Indira Gandhi as a contestant for the party was taken. According to him, ‘On May 19, 1979, until 7:00 pm, when MGR, Moopanar and I (R.V. Swaminathan) were talking in Delhi, MGR asserted that there is no doubt that ADMK will offer support to Indira Gandhi. Then, after MGR met with Morarji Desai at midnight, we noted a change in MGR’s thinking. Considering this change, the decision of not to have Indira Gandhi contesting the by-election was taken.

Even though the plan for Indira Gandhi to contest the Thanjavur by-election was abandoned, there was a covert agreement between the parties; that Congress (I) would contest Thanjavur, and ADMK would contest Nagapattinam by-elections, [both scheduled to be held on the same day].”

Coda

Well, anti-MGR press [including that which supported Tamil Nadu Congress (I) party leaders and DMK’s propagandists] promoted the view that MGR was either spineless, in betraying Indira at a time of her need or playing a ‘double role of running with the rabbit and hunting with the hound’ to Indira and her political rivals. Even if this may be so, after a passage of 45 years, vanities exhibited by Indira, Karunanidhi, Morarji Desai and the Tamil Nadu Congress Party (I) leadership also deserve a check. First, why should Indira depend on MGR’s leg to stand for her electoral success in Tamil Nadu? If she was indeed an all Indian leader, she could have contested the Thanjavur by-election and proved with a victory (even without MGR’s assistance). That should have proved her mettle as an all-Indian leader. This was not to be. Secondly, the spinelessness and unpopularity of her party’s Tamil Nadu leaders such as G.K. Moopanar, R.V. Swaminathan and R. Venkataraman, in trying to piggy-back on MGR’s popularity with the masses couldn’t be condoned as well.

Thirdly, what could be said of Karunanidhi’s stance of backing out of real contest at the Thanjavur by-election? Why he played ‘chicken’, and chose his colleague Anbil Dharmalingam to contest the by-election and lose against a less known Congress (I) candidate Singaravelu? He could have easily checked his mass popularity against MGR, in his native region by contesting the by-election and win. This he side-stepped.

Fourthly, Morarji Desai’s vanity and antagonism against Indira Gandhi also cannot be ignored. Suppose there was some truth that he had warned MGR to choose between either him or Indira, why he did not object MGR campaigning for non-Indira candidates from Congress (I) party? On principle, he should have demanded from MGR, not to campaign for any of the Congress (I) party candidates.

I concur with the opinion of Kannan that, ‘In politics, there is no right and wrong, and, perhaps, there is no honour. With time, Indira Gandhi in 1980 would ally with the DMK she had completely discredited during the Emergency.’

Cited Sources

Anon: Chikmagalur – spurious choice. Economic and Political Weekly, Nov 11, 1978; pp.1830-1831.

Anon: Congress (I) – Downhill all the way? Economic and Political Weekly, May 26, 1979; p. 896.

Morarji Desai: The Story of My Life, vol. II: Nehru and the Rise to Power of Indira Gandhi, Pergamon Press, Oxford, 1979, 398 pp.

Katherine Frank: Indira – The Life of Indira Nehru Gandhi, Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston, 2002, pp. 415-439.

Kannan: MGR – a Life, Penguin Books, Gurgaon, Haryana, 2017, pp. 223-286.

Karunanidhi: Nenjukku Neethi, vol.3, Thirumagal Nilayam, Chennai, 1997, pp. 310-318, 327-335.

Inder Malhotra: Indira Gandhi – A Personal and Political Biography, Coronet Books/ Hodder and Stoughton Ltd., Sevenoaks, Kent, 1989, pp. 201-213.

Nagorski, T. Clifton and R. Ramanujam: Making of a Martyr. Newsweek, Oct 17,

1977, pp. 5-7.

A.M. Rajasekhariah and R.T. Jangam: Chikmagalur parliamentary by-election: 1978 – a political analysis. Indian Journal of Political Science, Mar 1979; 40(1): 56-65.

Romesh Thapar New political pointers. Economic and Political Weekly, Nov 11, 1978; p.1834.

I lived in India during these days of political drama described by Dr. Sachi regarding Indira’s effort to get elected to parliament after her defeat in 1977 election. I had vague idea of events, but Thanks to Dr. Sachi, I could walk through those memories with much clarity detailing all the background information!