In a propaganda blitz, the military portrays itself as the guardian of Buddhism and stokes fear of a Muslim takeover.

by Billy Ford, Zarchi Oo, US Institute of Peace, Washington, DC, December 16, 2021

Buddhist monks protest the army coup of Myanmar in Mandalay, Feb. 27, 2021. However, monks have been less involved than they were in previous movements, such as the monk-led 2007 Saffron Revolution. (The New York Times)

Efforts to reinforce this critical narrative have intensified in recent months. News featuring public displays of military support for Buddhism have increased almost four-fold since the coup, according to a USIP analysis of the military-owned Myawaddy Daily and MRTV from August 2020 until November 2021.

Thus far, the propaganda blitz has had little discernible impact, though it may be helping the military stave off defections by its rank-and-file that could precipitate its collapse. Should these narratives gain traction with the public, however, they could undermine efforts to unify the opposition and spark inter-communal conflict. The military has had success generating fear about a Muslim takeover over the past decade, particularly among Buddhist communities in the Bamar heartland, where the anti-coup movement has had its most success recently.

The Military Attempts to Build Moral Capital and Rouse Latent Fear

The military has deployed four primary narratives to build its moral authority and generate fear that Burmese Buddhism and Myanmar’s sovereignty could crumble.

Narrative 1: The military is a pious institution with deep support from the Buddhist monastic community

Although the military has a history of violence against activist monks, and has arrested scores of non-compliant ones since the coup, it portrays itself as a pious institution with widespread support from within the Buddhist monastic community, the Sangha. USIP’s analysis found that Myawaddy Daily has run stories every day since February 1 that show military officers paying respect to Buddhist monks, visiting pagodas or making donations. Notably, the English-language section of the paper typically elides this imagery, offering an insight into the military’s domestic target audience.

Narrative 2: The military protects and promotes the Buddhist practice and philosophy

In its effort to demonstrate that it protects the Sasana (a Sanskrit term for Buddhist practice and philosophy), the military regularly displays photos of its campaign to vaccinate and provide basic goods to members of the Sangha.

![Photos on military-owned news sites of the military donating basic goods and vaccines.]](https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/2021-12/20211216-monks_vaccines_2-ac.png)

It also promotes a narrative that the Sasana is threatened by the National League for Democracy’s (NLD) apathy and that the democracy movement intends to destroy it. Just two weeks after the coup, the military publicized the re-opening of Buddhist sites closed due to COVID-19 under the Aung San Suu Kyi-led NLD government, demonstrating that the Sasana had supposedly declined under the NLD government while the generals were poised to rebuild it. The anti-coup movement, the military suggests, aims to destroy Buddhism. A recent op-ed in the Myawaddy Daily, for example, shows graphic photos of dead monks, alleging they were killed by the resistance movement.

Narrative 3: Min Aung Hlaing is a Buddhist warrior-king

Commander-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing has undertaken two major construction projects to insert himself into the warrior-king lineage. He is building three enormous statues of such figures in the Kokang region of northern Shan State near the Chinese border. Notably, none of the memorialized warrior-kings managed to control the Kokang region, which Min Aung Hlaing did as regional commander in 2009. The statues aim to amplify the image of the Buddhist warrior-king, while subtly allowing the coup maker to associate himself with them.

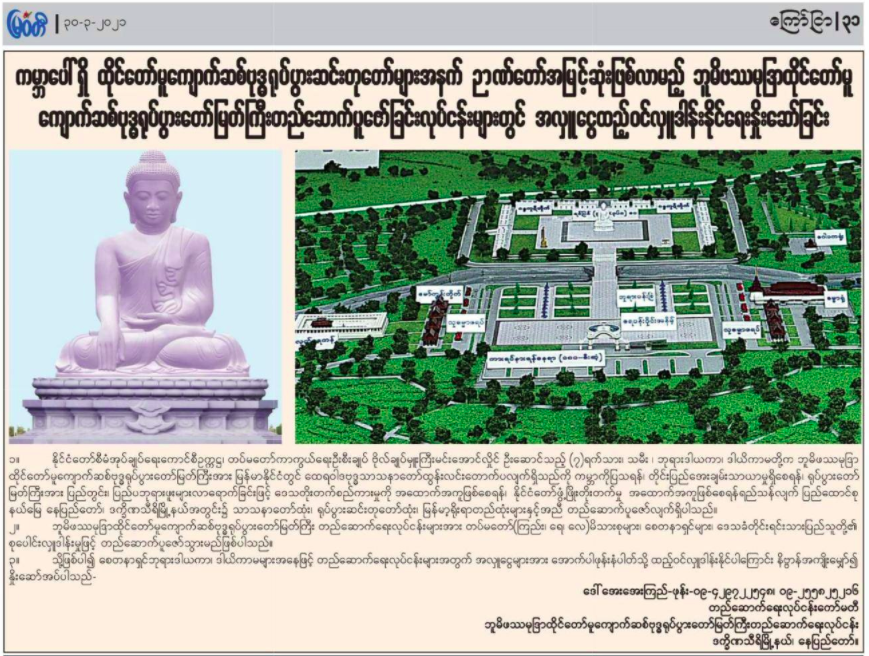

Min Aung Hlaing is also building what he claims will be the largest seated Buddha statue in the world. The project began before the coup but perhaps with a military take-over in mind; Min Aung Hlaing had the first stone placed on January 30, 2021, just a day before the civilian government was overthrown. The statue was not widely publicized until March 2021, once it became clear that the public would not accept the coup regime. On March 28, the day after the worst massacre by soldiers since the coup, the military published an op-ed in the Myawaddy Daily about the interdependence of the Sasana and the military. The next day, another op-ed saluted Min Aung Hlaing for this project, saying “cultural heritages, including Pagodas and monuments have been built by magnificent religious kings. Today, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing and his followers are similarly building the world’s largest seated Buddha image to prove that Myanmar is a religious contry, where peace and prosperity flourish.”

Military-owned media shows re-opened Buddhist sites across Myanmar.

Narrative 4: Myanmar is vulnerable to Muslim takeover

The military and its supporters also propagate the fabricated narrative of an imminent Muslim takeover and link the NLD and the anti-coup movement to Islam. Plugging into widely held Islamophobia nurtured for years by the military, the generals and their supporters spread narratives of Muslim influence on the NLD and the anti-coup movement, comparing the Peoples’ Defense Forces to the Taliban. Burma Monitor, a Myanmar-based civil society organization that tracks online hate speech and disinformation, catalogued numerous examples of this gambit, including doctored photos of prominent members of the shadow National Unity Government with full beards, one of them holding a large grenade.

More recently, the military junta’s spokesman, Zaw Min Tun, claimed that the army seized a cache of Turkish weapons that were delivered to anti-regime PDF fighters. To hammer the point home, he went on to say, “I assume that the OIC [Organization of Islamic Cooperation] is getting involved in the matter.”

The Military’s Weak Support Within the Sangha

The military’s success in spreading its narrative has been curbed by its limited base of support within the Sangha. Most notably, the highest Sangha body, the State Sangha Ma Ha Nayaka Committee (known as Ma Ha Na), issued a statement in March delicately indicating opposition to the coup regime’s State Administrative Council and signaling its intention to participate in the Civil Disobedience Movement. The statement capped numerous attempts by the chairman of Ma Ha Na, Banmaw Sayadaw, to discourage Min Aung Hlaing from launching the coup and engaging in violence. Ma Ha Na’s defiance was a startling departure from precedent and likely a major blow to military morale. After the statement, only three of the body’s 47 members body expressed public support for the SAC. Ma Ha Na has not made public remarks since, though Min Aung Hlaing met with Banmaw Sayadaw in early November.

Religious Actors Can Help Build Peace and Unity

Religious figures could still be transformative in the months ahead in two major ways.

As the military scrambles to assert itself as the protector of the Sasana, the Sangha could more actively to combat that narrative. Either by refusing military visits or openly supporting the anti-coup movement, efforts that undermine the military’s moral authority could weaken the regime and precipitate more defections, desertion or non-compliance from rank-and-file soldiers.

The anti-coup movement has brought the military to a historically weak position, politically and militarily. Revealing its desperation and strained resources, the military has even begun to arm and train the children and the wives of its soldiers. Nonetheless, the anti-coup movement has not fully unified. It is composed of a dizzying array of actors, many with competing interests and deep mutual distrust. Religious leaders, including Christians, Hindus and Muslims, could play an important role in facilitating dialogue and, eventually, pursuing reconciliation within the anti-coup movement that could establish a foundation for sustainable peace in Myanmar.

Zarchi Oo is a technical specialist for intercommunal harmony in Myanmar at the U.S. Institute of Peace.