My Magnum Opus – An Einstein Dictionary (1996)

by Sachi Sri Kantha

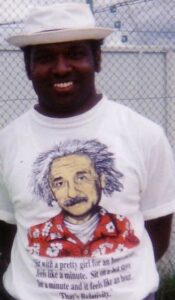

Sachi in a T-shirt with a popular Einstein quote (Osaka, 1993)

Between 1977 and 2015, I had authored/translated a total of nine books in Tamil (2 books) and English (7 books). In preparation of each book with diligence, I experienced delightful as well as nerve-wracking moments towards its completion. Here I describe the efforts taken to complete my magnum opus – An Einstein Dictionary, during the pre-digital era of airmail postal letters and FAX transmission. When I started the work in 1991, I was 38. It took five years to complete this mission, when the book was released in April 1996.

Initial Push from Physicist Prof. Abraham Pais (1918-2000)

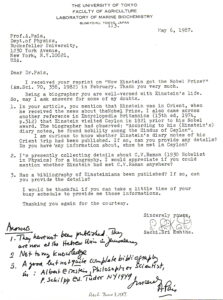

My interest in studying about Albert Einstein was stimulated, after my arrival in Tokyo in 1986, when I re-read Dutch-American physicist Abraham Pais’s 1982 study on how Einstein was awarded the 1921 Nobel prize in physics (American Scientist, 1982; 70: 358-365). In early 1987, I requested a reprint of this paper from Prof. Pais and received it promptly. Then, I wrote him an acknowledgment letter dated May 6, 1987, in which I asked him three questions. To my surprise, he responded by scribbling answers to the questions in my letter itself, and returned it by airmail. I reproduce it below. A PDF version is presented nearby.

Prof. A. Pais,

Dept of Physics,

Rockefeller University,

1230 York Avenue,

New York, NY 10021, USA.

Dear Dr. Pais,

Letter to Abraham Pais and response, May 6 1987

I received your reprint on ‘How Einstein got the Nobel Prize’ (Am. Sci., 70, 282, 1982) in February. Thank you very much.

Being a biographer you are well-versed with Einstein’s life. So, may I ask answers for some of my doubts.

-

- In your article, you mention that Einstein was in Orient, when he received the news about the Nobel Prize. I also came across another reference in Encyclopedia Britannica (15th, 1974, p. 512) that Einstein visited Ceylon in 1921 prior to his Nobel award. The biographer had observed ‘According to his (Einstein’s) diary notes, he found nobility among the Hindus of Ceylon.’ I’m curious to know whether Einstein’s diary notes of his Orient trip had been published. If so, can you provide any details? Do you have any information about, whom he met in Ceylon?

- I’m presently collecting details about C.V. Raman (1930 Nobelist in Physics) for a biography. I would appreciate if you could mention whether Einstein had met C.V. Raman anywhere?

- Has a bibliography of Einsteiniana been published? If so, can you provide the details?

I would be thankful if you can take a little time of your busy schedule to provide me these informations.

Thanking you again for the courtesy.

Sincerely yours,

Sachi Sri Kantha

Dr. Pais’s, hand written response was,

-

- They have not been published. They are now at the Hebrew Univ in Jerusalem.

- Not to my knowledge

- A good but not quite complete bibliography is:

Albert Einstein-Philosopher Scientist, P. Schilpp ed., Tudor, NY, 1979.

Sincerely,

A Pais

Shifting my interest from Raman to Einstein

In reality, as I had indicated in my letter to Prof. Pais, I was first interested in writing a biography of physicist Sir Chandrasekara Venkata Raman (1888-1970), the first Tamil scientist to receive a Nobel Prize for physics in 1930. Towards this objective, during 1987-88, I corresponded with Dr. Sivaraj Ramaseshan (1923 – 2003), a nephew of Raman and a distinguished crystallographer. Though he graciously sent me few reprints of his Raman-related publications, to say the least, my persistent queries about Raman by airmail letters somewhat irritated him. Only encouragement Ramaseshan gave me was, ‘I do recognize your positive interest in Raman’s life. It’s very tedious to continue written communications. If you visit India, we can ‘discuss these issues.’

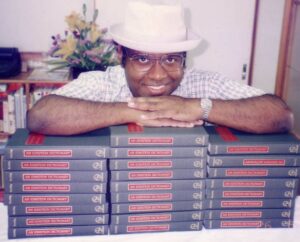

Sachi poses with his ‘Einstein Dictionary book, 1996

As a result, I opted to shift my attention from Raman to Einstein. A second contributing factor, other than Prof Abraham Pais’s 1982 book on Einstein, was my pen-pal correspondence with Dr. Jeana Gross (then affiliated to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel) in 1988. She was a carotenoid chemist, and senior to me by at least two decades. I confirmed this, because she had published her research on carotenes in Nature and Science journals in 1960s. It was indeed a delight for me, to hear from her. After reading a review paper I had published on legume carotenoids (Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 1987; 30 458-470), Dr. Gross wrote to me, requesting copies of few papers on carotenes published by Japanese scientists in Japanese journals, for a book she was then writing on carotenes of vegetables and fruits. I helped her. Then, our correspondence expanded to our other research interests and Einstein’s life cropped up. She did invite me to Israel once to guide me the locations having Einstein collections at the Hebrew University. She was also fluent in German language, would write teasingly, “I can be an interpreter between you and ‘your friend Einstein.’” Unfortunately, at that period, I was struggling with a young family and was without means. Being a Tamil native with a Sri Lankan passport, was also a minus point. Reluctantly, I had to miss that wonderful opportunity of visiting Israel, though having a scientist friend. After I moved to Philadelphia in January 1989, I was still in letter contact with Dr. Gross. Eventually, it got snapped. All I can write now is, ‘Dr. Gross, thanks for the pleasant correspondence on science matters, during 1988-89, and the ‘Einstein sparks’ you lit on me.’

T

hough I opted to concentrate on Einstein in preference to Raman, I did publish two items on Raman: one of which was a brief letter in the Nature journal [Raman’s prize, 1989; 340: 672], rebutting the claims of Russian physicists that Raman’s solitary award for the 1930 Nobel physics prize was well deserved.

A third contributing factor was a short letter I submitted to the Lancet journal on November 27, 1990, about Einstein’s illness was rejected! Nearby, I provide an image of this Lancet rejection letter. By temperament, I’m not one, who would wilt by a rejection. This positive frame of mind had helped me in my subsequent endeavors in life as well. I mildly inflated my ego, with the thought ‘Not to worry. If a letter get rejected, then why not write a book about Einstein. And I can do it.’

A Book Project on Einstein

On my 38th birthday (May 8, 1991), I submitted a book proposal to Ms. Cynthia Harris (then, an acquisition editor) at the Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut. For those interested in my submitted book proposal, I provide a PDF file of a copy. Book proposal to Greenwood Publishing Group re Einstein dictionary by Sachi Sri Kantha

By then, my first reference book ‘Prostitutes in Medical Literature; An Annotated Bibliography’ had been released, by the same publisher. Post publication reviews for this book was slow, but positive. I was told by the editor, that the print run for this book was only 600! The sale price for the book, at released year was $49.50.

The Einstein book proposal of mine was duly accepted. The date of contract, signed by me as June 13, 1991. According to the Agreement form signed, I would have to deliver my manuscript of ‘no more than 500 double-spaced pages on or before 1 January 1993’. Ms. Harris did let me know that the print run for Einstein will be higher (vaguely, around 2000-3000), because Einstein has name recognition. Due to this, the sale price per copy of this book will also be higher.

My objective was – ‘tackle something different in format, from what previous Einstein biographers had done’. But, due to the birth and child care activities of our second daughter Sangita in 1992, completing the Einstein dictionary in allocated time duration by the publisher was delayed by 18 months, from the originally signed deadline date. Sangita was conceived, after the acceptance of my book proposal. I also had to give a helping hand to my wife Saki, in caring our elder daughter Sachiko, who was 4 then. Due to pressure from my day job, I almost gave up on this book project; but persistence query of Ms. Harris, my Greenwood Press editor, did encourage me to complete the task at hand. My work motto has always been, ‘Better late, than never’.

Greenwood Press author questionnaire re Sachi Sri Kantha

Compiling the Einstein Dictionary

At that time, I was a postdoctoral researcher at the Osaka BioScience Institute. Among my young Japanese lab-mates, the word spread that I’m writing a book on Einstein. And a few of them encouraged me with gifts of Einstein paraphernalia, like a T-shirt, a monthly calendar, and a note pad. The photo of me, wearing an Einstein T-shirt in 1993, was one of these. My work routine then was from 9:30 am to 9:00 pm. Occasionally, I had to stay in the lab for observations in ‘night-shift experiments’ on rat sleep as well. Thus, I devoted reading and writing time for my dictionary compilation, from 11:00 pm to 3:00 am, while my wife, young kid and baby were sleeping. That four hours of undisturbed silence was indeed a gift for me. Then, I slept for four hours, until 7:00 am.

I cite excerpts from a letter sent by my editor Ms. Harris, dated December 27, 1993:

“Dear Dr Kantha:

…I would be glad to extend your deadline to March 1, 1994…

We do not schedule a work for publication until we officially accept the manuscript and move it into the production department…

Once a work is on the schedule, we try to move it along as quickly as possible. Copyediting generally take some six weeks from the time the manuscript is moved into production.

It generally takes some 9 to 11 months to publish a typeset book. Thus if you meet the March 1, 1994 deadline and no revision seems necessary, we could aim to publish the work by the end of 1994 and would certainly be able to publish it early in 1995. Thus the publication date will depend to a large extent on when we receive a complete and acceptable manuscript…

Sincerely,

Cynthia Harris

Executive Editor – Reference Books.”

This letter I received in Osaka on Jan 4, 1994. To shorten the time lag of 5-7 days taken for airmail delivery, we used FAX transmissions routinely. I received a 6 page length review of my penultimate version of the manuscript submitted to Ms. Harris, in March 1994. Excerpts:

“Dear Dr. Kantha:

Thank you for your letter of March 1 and the penultimate version of your manuscript. I am glad to know that it is nearing completion, and I have just finished reviewing the manuscript. The material is quite interesting, and I believe you are well on your way to providing a fascinating book. However, the manuscript could benefit from a bit more work…

Although most of the quotations in your book fall within fair usage, a few do not. I you quote from more than one line of copyrighted verse or poetry, you need permission from the publisher. Thus you need to obtain letters of permission for the material quoted on pages… You should check all your quotations and write for permission to use those lines that exceed fair usage…

Your indication [in the Preface] that the book is for a ‘popular’ audience isn’t quite right. Although the book is for the layman who is not necessarily trained in science, we will not be marketing the book to a mass market, or popular market. The market will still be essentially the college and university library and possibly the public library. Thus you need to adjust the statement regarding the potential reader slightly.

Although some of my requests may lead to a longer work, that will not pose a problem. I had in fact anticipated a somewhat longer book. The contract allows for a work of up to 150,000 words, and I would estimate that the manuscript is less than 90,000 words…

I hope you will not be discouraged by the length of this letter. Despite its length, I am still very enthusiastic about the book. The information that is given picques my interest and makes me want to know more about Einstein. Once you have provided that additional information – information that provides a full picture of the man – you will have a fascinating book.

I continue to look forward to its completion.

Sincerely,

Cynthia Harris.”

I did accept all the criticism and suggestions for improving the text material of Ms. Harris. This was because, between 1992 and 1995, I was able to write five sole authored, Einstein-related papers, in the Medical Hypotheses journal. And this parallel task, based on the materials I had collected for writing the dictionary offered me energy and strength. These were, as follows. Apart from the publication dates of these five papers, one should also note the dates of submission and acceptance indicated.

✦Albert Einstein’s dyslexia and the significance of Brodmann Area 39 of his left cerebral cortex. Medical Hypotheses, 1992; 37: 119-122. date of submission Aug 20, 1991, date of acceptance Oct 5, 1991.

✦An appraisal of Albert Einstein’s chronic illness. Medical Hypotheses, 1994; 42: 340-346. date of submission June 3, 1992, date of acceptance Aug 28, 1992.

✦Is Karl Landsteiner the Einstein of the Biomedical sciences? Medical Hypotheses, 1995; 44: 254-256. date of submission June 7 1994; date of acceptance Aug 24, 1994.

✦Einstein’s medical friends and their influence on his life. Medical Hypotheses, 1996; 46: 257-260. date of submission July 19, 1995; date of acceptance Aug 23, 1995.

✦Scientific productivity of Einstein, Freud and Landsteiner. Medical Hypotheses, 1996; 46: 467-470. date of submission No 7, 1995; date of acceptance Nov 27, 1995.

After I submitted to complete typescript to the Publishers, I had to complete a pre-publication author questionnaire for Greenwood Press, to facilitate book promotion. After completion, I submitted this on September 1, 1994. In it, I had written,

“40th anniversary of Einstein’s death falls in March 1995; also, the 90th anniversary of Einstein’s first publication on the theory of relativity also falls in mid-1995. Thus, the release of this book in early 1995 is timely to tie in with these two anniversaries.”

I provide a PDF file of the complete pre-publication author questionnaire nearby. I received an advanced paycheck for US$ 500. This was the only remuneration I received from the publisher. Opposed to this, I had to pay more than $1,250 from my wallet, for copyright permissions for quoted poetry lines etc. used in the book.

The dedication page of the book, read as follows

“To my father Sivapragasam Sachithanantham, who provided support and guidance despite his son’s failures on many fronts;

Sangita, whose birth in 1992 postponed the birth of this book by a year; and

Sachiko, who tolerated her father’s robbing of her ‘play time’ with stoic patience.”

Production period for the book lasted more than a year. By that time, I had moved from Osaka to another smaller city (Fukuroi), due to joining a small Japanese food company on Feb 1995. The dictionary was released only in April 1996. I was NOT told about the print run for the book, by the publishers, though I did inquire on this, with my corresponding editor. The original selling price of the book was $75.00, for a 336 pages book. I was not consulted about the book cover at all. I received one complimentary copy of the book, from the publisher, and purchased 24 copies (at a 40% discount) from the publisher for distribution to my mentors, friends and those who had supported me. Once these arrived from Connecticut by sea mail, a photo of this collection was taken by my wife Saki.

Now almost 29 years had passed, with the digital trends that picked up since 2000, the publishing company (Greenwood Press) had undergone mergers and vanished. Still, I do receive belated annual royalty statements from the new publishers (Bloomsbury group), which had acquired/incorporated the Greenwood Press catalogue. But still, no royalty paychecks. I was told many years ago that I’ll receive royalty payments only AFTER my dividends tops $100. It’s still hovering around $35! Nevertheless, the book is still being sold in the Net by many vendors at double or triple tag prices of the originally set selling price of $75. Someone is economically profiting from my five year labor, but it’s NOT me.

Post-publication Peer Reviews from Mentors and Pals

What was soothing to my tired mind was the complimentary words from my mentors and pals, on my achievement. I present eight of them below. The first listed three from USA, were my mentors in science. Prof. Kenichi Fukui (1918-1998), who kindly contributed the foreword for the book at my request, was a co-Nobelist in chemistry for 1981. He was the first chemistry Nobelist from Japan. Meeting him with my family in Kyoto and convincing him to contribute a foreword for this book was a pleasant experience. To my regret, exactly a year after he sent his 1997 New Year greetings to me, he died! Dr. Jagdish Mehra (1931-2008) was an Indian-American physicist and science historian; He was also a biographer of physicist Richard Feynman. It was a complete surprise for me, to hear from him. Though I didn’t know him personally, I had recognized his publications in physics and included an entry on him, in my dictionary. Dr. Samuel Coleman, an American anthropologist, whom I acquainted in Osaka, was a fellow researcher and senior contemporary in the history of Japanese science. Mr. Fusao Hagiwara, a pal of the Japanese food company I worked when the book was published, was an engineer who was employed at Nestle Foods, Japan. Dr. Hubert Hug (from Germany) was a pal during my Osaka Bioscience Institute days. Like me, he was also a post-doctorate fellow. Me being illiterate in German language, he was a great help to me in deciphering Einstein-related published literature, and checking Einstein’s publications.

✦ “Sri – Thank you so much for the book and follow-up letter. I very much enjoyed reading through ‘An Einstein Dictionary’. That was a unique approach to cataloging his life. Edie also skimmed through the book.” (Prof. John W. Erdman Jr,, University of Illinois, Dec. 22, 1996).

✦ “Sri – Thank you very much for the autographed copy of your ‘An Einstein Dictionary’. I did read the preface; I had no idea you had intended a career in physics! I’m sure your father is more than happy with your many accomplishments.” (Prof. A Catharine Ross, then at Pennsylvania State University, Dec. 15, 1996).

✦ “Dear Sachi – Thanks for your letter of June 23, as well as the inscribed copy of your new book ‘An Einstein Dictionary’. Congratulations on the publication of this very interesting volume.” (Dr. Eugene Garfield, Chairman Emeritus, Institute for Scientific Information, Philadelphia, Aug 14, 1996)

✦ “Dear Dr. Sri Kantha, Your Einstein book is eternal! (Prof. Kenichi Fukui, Kyoto, Jan 9, 1997).

✦ “Dear Dr. Sri Kantha, I ordered a copy of your book ‘An Einstein Dictionary’, and noticed the entry on me in it. Thank you for including me in your Dictionary.” (Prof. Jagdish Mehra, Houston, Texas, Dec 16, 1996)

✦ “Dear Sachi – Just a short note to congratulate you on the publication of your Einstein Dictionary. Quite a feat!” (Dr. Samuel Coleman – then at University of New South Wales, Sydney, April 16, 1996).

✦ “Dear Dr Sachi Sri Kantha – Congratulations on the publication of your new book ‘An Einstein Dictionary’. Great that your hard effort has made it completed with applause. Appreciated the book by you.” (Mr. Fusao Hagiwara, Nikken Foods, Fukuroi City, Japan).

✦ “Dear Sri – Thank you very much for your Einstein Dictionary. It looks very nice. I am very pleased about it. What is your next project?” (Dr. Hubert Hug, then at Centrum fur Molekulare Biologie, Universitat Heidelberg, Oct 8, 1996).

Among the eight felicitations mentioned, Prof. Fukui’s one (the briefest) was a take from Einstein’s quote ‘Politics is for the moment; an equation is for eternity’. I was delighted by Prof. Fukui’s choice of words.

Published Book Reviews

Between 1996 and 1998, 4 reviews of the book (of varied length) appeared. In chronological order, these were as follows:

✦College & Research Library News, Oct. 1996, vol. 57(9), p. 601, by G. Eberhart.

✦Choice, Oct. 1996, p. 252, by J.C. Shane.

✦American Reference Books Annual, 1997, vol. 28, pp. 638-639, by C.D. Hurt.

✦Isis, 1998, vol. 89(1), p 175, by L.M. Brown.

While three short reviews were appreciative, the lengthiest (713 words) that appeared in the American Reference Books Annual of 1997, by C. D. Hurt (with the affiliation, Director, Graduate Library School, University of Arizona, Tucson) was unappreciative and negative. The only information I could gather now about this reviewer Prof. Charlie Deuel Hurt was that he had authored a book ‘Information Sources in Science and Technology’ in 1998. He was neither a scientist nor an Einstein scholar! He had NOT published a paper about Einstein or any other reputed scientist in physics or other related disciplines in chemistry or mathematics or astronomy. For record, I provide in full, this negative review by Prof. Hurt.

“This book is an enigma, starting with the title. The arrangement of the material in the work is indeed alphabetic, but that is where the resemblance to a dictionary stops. The work is a compilation of trivia, short vignettes of one or two paragraphs, and miscellany. The glue that binds them all together is the fact that they all have something to do with Albert Einstein.

In addition to the entries, there are other facets to the book. There is a standard chronology of Einstein’s life that continues with events related to Einstein in 1993. There is a short ‘Readers’ Guide’ to biographies and other sources consulted. There is an awkwardly done and graphically ugly genealogy chart. The chart appears to have been done partly by a distinctly unsteady hand and on a typewriter. There is a section listing all of Einstein’s scientific publications. A further section lists journal articles. In this case, ‘journal articles’ means popular articles about or by Einstein. A curious section follows, entitled ‘Books’. This runs the gamut from writings by Einstein through politics and public issues to Einsteiniana. These facts are, however, only tangential to the main body of the work. Nonetheless, a reader will be able to make use of these sections for additional or corollary information by or about Einstein. In doing so, the reader will have to interpret the categories and intentions of the author.

The foreword to the book suggests that there are two ‘riddles’ to the book. The first is why it was written by a biochemist and second, why the foreword was written by a chemist. Neither is a real riddle, because the work Einstein began moved quickly into chemistry and biochemistry via quantum chemistry and other avenues. The riddle of the book is what audience it is supposed to address. If this is a scholarly work, then it falls short simply because the entries are not as replete as they should be. If this is intended as an entrée to Einstein, it misses the mark because to use the book at all, one needs to have some prior knowledge of Einstein. On the scholarly to popular continuum, this book falls closer to the popular. It is not clear at all that this is where the author intended this book to fall.

The majority of the book is a series of entries arranged in alphabetic order. For each of the entries there is varying information given, ranging in length from a couple of lines to substantive paragraphs. The problem with the intended audience of the book makes for curious entries. Max Planck is listed with a reasonable five-paragraph entry; Planck’s constant is not mentioned except inside the entry on Planck – black body radiation, the genesis of Planck’s work, is not mentioned at all. Curiously, there is no mention of tensor calculus, which was a major factor in allowing Einstein to place all space-time coordinate systems on an equal footing, leading to the general theory of relativity. This was critical to Einstein’s concept of general covariance (which also is not among the entries in this book). For the entries that are missing, there are entries that stretch the connection to Einstein. Einstein on the Beach, an opera in four sets, is listed. There is an entry for Archibald MacLeish, the poet and later Librarin of Congress, who wrote a fairly lengthy poem ‘Einstein’.

On the production side, the inequalities in the typeface fonts between the main text and the tables are disconcerting. In some cases, the tables could have been more carefully integrated into the text or placed with the entry that references them. In a book short on so many important aspects, the typography and composition are unfortunate victims. On the plus side, the index is useful.

This is a book that is difficult to recommend. It has some features that make it interesting, but only if it is a part of a larger collection of Einsteiniana. Even then, the price is out of line with the benefit of owning the book. With so much other material on Einstein available, this work suffers. If the goal is to have everything published in Einstein, then this is a candidate for purchase. With any less aggressive collection development strategy, this work cannot be recommended. [R: Choice, Oct 96, p. 253]

In contrast to this, the review by Laurie M. Brown which appeared in the science history journal Isis (1998; vol. 89, p. 175) was a positive one. It was this.

“An Einstein Dictionary, to my surprise, made for more interesting reading, because of its colorful entries and extensive bibliography and index. The entries, arranged alphabetically, include such noteworthy subjects as ‘Nobel prize’, ‘Literati and books’, ‘humorous verses’ and ‘dyslexia’. Under ‘collaborators’ there is a table of Einstein’s fellow researchers, thirty one in number. Verses written by Einstein appear under ‘poetic expressions’. From ‘popularity surveys’ we learn that a 1991 doctoral dissertation on perceptions of influential world figures found Einstein ranked sixth, just after Gautama Buddha. The dictionary entries often provide useful references.”

Responding to a hostile Reviewer

Among the published authors, two traditions prevail. One is to completely ignore the published reviews of the books. The other one is to respond (either publicly or privately) to negative notices. I opt for second tradition. My reasons are: (1) to acknowledge the time and energy, a reviewer had taken the trouble to read or skim my book. (2) Reviewers are not all knowing oracles. They also have their blind spots, and may be educated/informed, on the intention of the author. As such, on Feb 11, 1998, I sent an airmail letter to Prof. C.D. Hurt commenting about his review to the American Reference Books Annual – 1997. I’ve retained a copy of what I wrote. The text was as follows:

“Dear Dr. Hurt:

I was pleased to read your review of my book An Einstein Dictionary, in the American Reference Books Annual 1997, vol.28, pp. 638-639. Thank you for commenting succinctly on the merits and demerits of my book. I agree with most of your comments. However, I felt that you may be interested in hearing my response as well. Hence, this letter.

First, regarding your comments on the production aspect of the contents such as ‘awkwardly done and graphically ugly genealogy’, ‘inequalities in the type face fonts between the main text and the tables’, as an author, I didn’t have the final say. I did what my editor of the book requested me to do. In this aspect, I think Einstein himself was not an adherent of fashion and style. I cite two of my favorite quotes of him, on this theme.

‘I adhered scrupulously to the precept…matter of elegance ought to be left to the tailor and to the cobbler.’

‘It’s not good if the wrapper is of better quality than the meat it covered.’

I sacrificed fashion and elegance for accuracy and useful information, and that would have satisfied Einstein.

Secondly, I thought that I have described clearly in my preface who is the intended readership for this book. It is not a ‘riddle’ as you have mentioned. The book was not aimed for physicists, but for scientists who are not well-versed in physics. Majority of the scientists have heard about Einstein, but they cannot explain in simple terms, what Einstein did to claim his rank among the immortals. Prof. Kenichi Fukui (who graciously contributed the foreword and who knows his beans) correctly comprehended my objective. Also, another reviewer of my book, G.M. Eberhart [College & Research Libraries News, Oct. 1996, p.601 – a copy enclosed herewith] also has identified the usefulness of my reference book ‘as a quick fact-finder’. I will be pleased if you can refer to me another book on Einstein which provide so much information on Einstein in 325 pages in a readily accessible, reader-friendly format? I think, my contribution to Einsteiniana should be looked from this perspective.

In sum, I wish to stress that my comments do not in anyway cast aspersions on the credibility of your excellent review, which I value very much. With best wishes.”

To my regret, I never heard from this reviewer. In fact, living in Japan, other than Prof. Kenichi Fukui whom I met face to face and convinced him to contribute a Foreword to the book, from 1991 to 1996, I had to deal with other individuals living in USA (from the editors of Greenwood Press, fellow physicists such as Prof. S. Chandrasekhar, Prof. Gerald Holton, Prof. Jagdish Mehra, copyright permission agencies and copyright holders, and post publication correspondence with Prof. Kenji Sugimoto, a fellow Japanese ‘Einstein – crazy nut’) mostly by airmail letters and fax transmissions. This correspondence itself may be compiled into a mini-book of more than 100 pages.

Recognition as a Contemporary Author in 2000

What made me happy was that, based on the merits of my two sole-authored science reference books – Prostitutes in Medical Literature (1991) and An Einstein Dictionary (1996), both published by the Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut, I received an entry in the Contemporary Authors (vol. 184, Gale, Farmington, Michigan) reference listing in 2000. The letter first received from Ms Elisabeth A. Cranston, editor, dated Dec 3, 1999, is provided in a PDF file. Contemporary Authors request to Sachi Sri Kantha 1999

Though scientists also ‘write’ and publish research papers in their specialty journals, and occasionally single-authored books, majority of the entries in the Contemporary Authors series belong to the literary field – novelists, short story writers, playwrights, poets, biographers etc. Only a few notable scientists (in the caliber of Peter Medawar, Alex Comfort, Edward O Wilson, James D Watson, Stephen Jay Gould, and Abraham Pais qualify as ‘Contemporary Authors’). I felt pleased that my work on Einstein has been taken into account as a reliable ‘biography’ in a varied format.

When I joined the University of Illinois in 1981, I had copied my favorite American author James Michener (1907-1997) entry in the Contemporary Authors volume, and preserved in my note book, as an amulet for inspiration in English writing. Michener became my literary idol, after I watched the ‘Sayonara’ movie (1957; starring Marlon Brando, Red Buttons and Miyoshi Umeki) based on his 1953 novel. I was also born in 1953. So, I felt a ‘predestined link’ to this Michener classic, the title of which means ‘Farewell’ in Japanese language. Michener still remains as my literary idol, because of his campaign against racism in American society in the Sayonara novel and his story telling skills as a writer. Eventually, three years after Michener’s death, it was a honor for me to touch a platform my idol stood elegantly.

Coda

Einstein’s life still continue to stimulate me. Other than the five papers I had written during the preparation period of my dictionary, I also had published two letters on Einstein in the Nature journal, and subsequently two more papers. These are:

✦Einstein in Zurich. Nature, Jan 12, 1989; 337 110.

✦Einstein and Lorentz. Nature, Jul 13, 1995; 376 111.

✦Total Immediate Ancestral Longevity (TIAL) score as a longevity indicator an analysis on Einstein and three of his scientist peers. Medical Hypotheses, 2001; 56(4) 519-522.

✦Humour on Einstein as expressed in limericks. Current Science, Mar 25, 2015; 108(6) 1170-1172.

Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) defined a lexicographer idiosyncratically as ‘a harmless

drudge, that busies himself with tracing the original, and detailing the signification of

words’. With my tangential Einstein book, I did join the illustrious company of Samuel

Johnson, Eric Partridge (1894-1979) and William Safire (1929-2009).

*****

Very interesting collection of memoirs indeed.

I felt philosophical about this:

“Nevertheless, the book is still being sold in the Net by many vendors at double or triple tag prices of the originally set selling price of $75. Someone is economically profiting from my five year labor, but it’s NOT me.”

A plant nurtured by a good hearted farmer is benefitting many passers by, but not the farmer!