by Sachi Sri Kantha, March 11, 2022

35 years will pass on June 4, 1987, when the then Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi executed his machismo pretense for the Eelam Cause by providing relief air-drop to Jaffna Tamils, who were suffering from the Sinhalese military onslaught. At that time, every Sinhalese politician, pundit, and journalist cussed Rajiv for siding with the Eelam Tamils. He became a darling of these tribes (the ilk of Mahinda Rajapaksa, Dayan Jayatillake and Rohan Gunaratna), only after his death on May 21, 1991 in Tamil Nadu.

Screen grab of the song (Penn Paarka Maapillai) scenario – M.R. Radha and Rajasulochana

Recently, after listening to one of Kannadasan’s ever- green lyric, sung by K. Jamuna Rani, in ‘Kavalai Illatha Manithan’ [The Guy without any Worry, 1960], I inferred that the King poet might have had a premonition of what may happen in Jaffna in June 1987. His pathos-tinged song. – ‘Penn Paarka Maapillai Vanthar’ [The bridegroom visited to see the bride] was a marvelous gem of a song and a very popular hit song in Radio Ceylon.

I provide a brief background of the scenario in which this song appears. The guy, a lothario (played by actor M.R. Radha) befriends a young woman (played by actress Rajasulochana), makes her pregnant and washes his hand from her. He was set to marry another woman. But, through a good natured manipulation executed by the lothario’s younger brother (played by comedian J.P. Chandrababu) and the woman (played by actress M.N. Rajam) who was about to get married to the lothario, at the wedding ceremony the cheated woman sits in the bride’s place; and the lothario ties the sacred ‘thaali’ to her. During the first night scene, the dialogue between them was as follows:

Lothario: ‘Are you crying? You are standing as if not having a musical taste. When I came to see you for the first time, you sang a song, with a cry. Now, why not sing a song, with a smile?’

The cheated bride: ‘What should I sing about? About the past experience, or on the future dream?

Lothario: No –no. You don’t have to sing about the past or future. I have come to see you. Will you sing about me?

Then, the cheated bride sings, while walking outside the room. The original lyrics in Tamil is provided nearby, and I give an English translation of it below.

To see the bride, came the (Bride)groom

To see the bride, came the (Bride)groom

He came; indeed he came!

Is it lust in one’s eyes or is it the speed of one’s hands

Even when the heart aches, will there be new feelings?

Even when thoughts de-rails, the bond wouldn’t change

In the justice of femininity, is it a bond of Nature?

In the white jasmine garden, will the gold beetle sing?

When gold beetle sings, will there be gentle breeze?

When the gentle breeze sways, will the season’s muse?

When the season’s muse, will it be devoid of merit?

Among the children born in earth, countless are crores

Among the countless crores, half are women folks

The love of such women folks, men are in need

They arrive to exchange wedding garland in the stage.

For those interested, the YouTube link of this song is as follows: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G1h3hs722bA

At the end of the song, the Lothario comes toward the cheating bride and extols: ‘What a beautiful voice, sweet voice!’. With this vintage Kannadasan’s lyric (written probably in late 1959 or early 1960), we can equate Rajiv Gandhi of 1987 as the political lothario, who visited Jaffna to see the Eelam bride. She was given hope, and subsequently abandoned. Metaphorically, every line of this song, fits the Rajiv’s machismo scenario of 1987, including the title of the executed Operation – Operation Flower Garland. In fact, Kannadasan was the producer of this movie.

For digital record, from my collection, I provide 7 contemporary items which appeared in the Economist, Time, Newsweek, Far Eastern Economic Review and Asiaweek below, about Rajiv’s lothario politics. The sentiments of Eelam Tamils and the Sinhalese folks are well presented in these items. It is often said that, journalists record the first, incomplete (often inaccurate) history of events. Be that as it may, due to their efforts, at least we have this incomplete record of Rajiv Gandhi’s machismo-lothario politics. To the best of my knowledge, no academics had published a critical study on this particular episode of Rajiv’s almost 10 year old political career, from 1982-1991.

Time’s coverage of June 15, 1987, incorporating Qadri Ismail’s coverage from Point Pedro, provides minimal background hints on why Tamil youths joined the LTTE, in their fight against the Sinhalese-dominated Sri Lankan army, and why Tamil rebel groups who collaborated with the Sri Lankan army were decimated by LTTE. The same Qadri Ismail (1961-2021) subsequently received his Ph.D. in English from Colombia University in 1998, and became a faculty member at the University of Minnesota.

- Special Correspondent: The Tiger hunt and the failed armada. Economist, June 6, 1987, pp. 27-28 & 31.

- Lloyd Garrison, Qadri Ismail, Venkat Narayan: The Gandhi Airlift. Time, June 15, 1987, pp. 18-19.

- Rod Nordland, Sudip Mazumdar, Mervyn de Silva: A Bad-Neighbor Policy. Newsweek, June 15, 1987, pp. 10-11.

- Salamat Ali: Trespass from the Air. Far Eastern Economic Review, June 18, 1987, p. 10-11.

- Salamat Ali: The unarmed intervention. Far Eastern Economic Review, June 18, 1987, p. 10-11.

- Anon: More in the War of Words. Time, June 22, 1987, p. 19.

- Sri Lanka Options. Asiaweek, June 28, 1987.

Note that the spelling of Tamil names of individuals and places are as that in the original and have NOT been corrected for conventional format.

The Tiger hunt and the failed armada.

[Special Correspondent: Economist, June 6, 1987, pp. 27-28 & 31]

Satyagraha, or soul-force, may have pushed the British out of India, but it is not having much impact on the Sri Lankans. The Indians tried some Gandhian peaceful intervention in Sri Lanka’s civil war on June 3rd, sending fishing boats packed with humanitarian aid and journalists out into the Palk Strait that separates the southern tip of India from its little neighbour. Near the island-dot of Kachchativu the Sri Lankan navy stared hard at them – and the boats went home again. The maritime comedy would have done no good at all to the Indian prime minister, Mr. Rajiv Gandhi, and India was quick to respond to its naval humiliation. On June 4th the Indian air force began parachuting relief supplies into the Jaffna peninsula.

The confrontation has brought relations between Sri Lanka and India to their worst point in decades. For two years the countries have been engaged in fairly friendly negotiations over the Tamil rebellion in Sri Lanka. India has presented itself to the Tamils as their protector (southern India contains a lot more Tamils than Sri Lanka does), and to the Sri Lankan government as a helpful mediator On the whole, the Indians have been constructive and Sri Lankan has been grateful.

This year, however, the negotiations got stuck. The Sri Lankan government has given a fair amount of ground, offering to devolve lot of power in the Tamil areas of the island, but it would not budge beyond a certain point. The more extreme Tamils – probably still a minority of the Tamil community – continued to insist on an independent state, Eelam, and they have threatened to declare independence for the Jaffna peninsula, which is controlled by the main guerrilla group, the Tamil Tigers. The Sri Lankans launched a successful offensive in the Northern province earlier this year. The Tigers replied with some particularly brutal acts of terrorism. On May 26th the government set out to recapture the Jaffna peninsula, or most of it.

It would be more comfortable for Mr Gandhi if the Sri Lankan government left its Tamils alone. The Sri Lankan army has killed a lot of Tamil civilians in past operations. Mr Gandhi has 50m Tamils in southern India who sporadically riot about what is happening to their fellow-Tamils over the water. He also has to think of his role as leader of a regional superpower.

India’s government would not relish the creation of an independent Eelam: victorious guerrillas in Sri Lanka might encourage all sorts of Indian separatists, in Punjab, West Bengal and elsewhere. But the Sri Lankan army’s attack into the Jaffna peninsula seemed to require some action. The area is densely populated, and almost all of its 850,000 inhabitants are Tamils. Civilians are certainly suffering. The Indians claim that several hundred have already died in the latest fighting: the Sri Lankans say only a handful have, both sides’ figures are suspect. So, with much publicity, the aid flotilla was got together at the port of Rameswaram on the Indian shore.

Sri Lanka’s President Junius Jayewardene threatened to intercept the boats, unperturbed by the certainty that any serious military clash between India and Sri Lanka would leave the island with all the bruises. He may have been encouraged by a suggestion that Pakistan might, somehow, offer him help, but as one Indian government official put it, “If we wanted to, we could smash up Sri Lanka in 40 minutes.”

The Sri Lankan government maintains that it can look after the needs of the Jaffna peninsula’s people. But the part of the peninsula still held by the Tigers has been under virtual siege since the government began its offensive. Food is in short supply: onions and chillies are grown locally, but alone they make a mean meal. Constant curfews make the distribution of food, such as there is, difficult.

If the Indian flotilla has done nothing else, it has checked the Sri Lankan army’s offensive. Its attack had been planned in three stages – first an assault on the Tiger stronghold in the north-east of the peninsula, then a move westwards from there, accompanied by a move up from the south, and lastly an attack on Jaffna town itself. Most of the Tigers’ defences are there: almost 500 guerrillas are believed to be dug in among the town’s 175,000 civilians.

By midweek the offensive had paused at the end of stage one, partly because of the Indian diversion, but also because the army had found it unexpectedly difficult to root out the Tigers. The guerrillas had dug themselves into well-made bunkers and had peppered the place with mines. Most of the peninsula was still under guerrilla control, and on June 3rd the Tigers bombed an army building in the besieged military base inside Jaffna town.

The government now has to decide what to do. An attempt to take the town would mean a lot of civilian casualties, and would probably recruit new support for the Tigers among the Tamil community. One Colombo Tamil, thinking of recent Indian history, has described the army’s assault on the Jaffna peninsula as ‘India’s attack on the Golden Temple, writ large’. A Tamil woman expressed a common view: ‘We do not agree with a separate Tamil state. It is a nonsense on such a small island. But our boys are being massacred by the army, so we are sending them money.’ With neigher an assault on Jaffna town nor a siege of it as plausible options, it is hard to see where the government goes next.

*****

The Gandhi Airlift.

[Lloyd Garrison, Qadri Ismail, Venkat Narayan: Time, June 15, 1987, pp. 18-19]

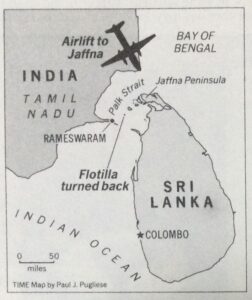

The five Soviet-designed An-32 military transports roared across the 22-mile Palk Strait and began their descent over Sri Lanka. Overhead, their swept-back wings glinting in the late afternoon sun, four French-made Mirage jets flew protective cover. At about 1,200 ft., the Indian air force transports opened their giant rear doors and dropped their payload – 22.5 tons of food and medicine – over the village of Kokuvil, three miles north of Jaffna. All that was visible below was empty streets and lush greenery as the planes parachuted their cargo to Tamil civilians. Less than an hour later, pilots and crews landed safely at India’s Bangalore air force station.

TIME map of Sri Lanka, June 15, 1987

So ended Eagle Mission -4, an operation aimed ostensibly at providing relief for ethnic Tamils caught up in a weeklong offensive by Sri Lankan forces. That the airlift also had a political objective was made clear minutes after the drop as the five An-32s pointedly flew over Palaly, the busiest air base in Sri Lanka. By flaunting its vastly superior air power over its weaker Indian Ocean neighbor, New Delhi gave notice that it no longer considered itself neutral in the four-year-old war between the Sinhalese-dominated Sri Lankan government and the separatist guerrilla forces seeking independence for the Tamil minority.

In a note handed to the Sri Lankan High Commissioner in New Delhi, the Indian Ministry of External Affairs called the mission ‘humanitarian assistance’. But to Colombo, it was a ‘naked violation of Sri Lanka’s independence.’ Colombo’s daily Sun newspaper called India a ‘predator of the worst kind’. For many, the anger was overshadowed by despair: Sri Lankans know they cannot take on the might of their giant neighbor. Complained a Sinhala shopkeeper bitterly: ‘They may shout, but when we are in trouble, America and China do nothing to help us.’ Whatever Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s motives for the drop, its effect was to edge his government perilously close to open conflict – a prospect that neither side wants.

The week began with Sri Lanka’s armed forces completing the first phase of Operation Liberation, its long-awaited drive against the Tamil rebel stronghold in the Jaffna peninsula, which lies opposite India’s southern coast. The area’s civilians had already endured some hardship from recent fighting and a five-month-long cutoff of fuel supplies and telephone service. Backed by air support and naval gunfire, Sri Lankan troops seized all the territory around Valvadditturai. The town’s importance was both strategic and symbolic, since it is an operational center for the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, the main Tamil separatist group, and the birthplace of its leader, Velupillai Prabakaran. In the process, government troops sealed off key landing sites for supplies ferried across the straits from Tamil rebel bases in southern India. Colombo claimed that casualties on both sides had been light: 29 soldiers dead and 16 wounded, with 87 guerrrillas and 41 Tamil civilians killed.

TIME’s Qadri Ismail, who flew aboard a Sri Lankan government plane into newly captured Point Pedro, found little recent battle damage there. But his requests to visit Jaffna and Valvadditturai were denied by Sri Lankan authorities. While many Point Pedro civilians were hungry, the army appeared to be making an effort to bring in supplies. When soldiers in an army truck arrived in the town of Nellandai and began handing out rations, civilians ran to the truck and scuffled with one another over the handouts. A mother with a child in her arms watched helplessly until a journalist noticed her plight and brought her a food packet.

Other army units, meanwhile, were busy mounting a dragnet aimed at depopulating the area of all male Tamils of fighting age. Outside the Pathirakali Amman temple in Nellandai, more than 600 barefoot youths with their hands tied could be seen marching four abreast toward Point Pedro, a mile away. One woman, with tears streaming down her face, cried, ‘Give me back my son! Why do they take him away?’

‘All of them cannot be terrorists,’ conceded General Cyril Ranatunga, commander of Sri Lankan forces. ‘But still we will get some of them.’ At Point Pedro, the youths were lined up against a wall, while rebel defectors, with gunny-sacks over their heads to conceal their identities, walked down the line pointing out Tiger suspects. The few who were recognized were separated from the group. The rest were put aboard a ship waiting at sea. Their destination: Boosa detention camp, 300 miles from their homes. ‘To me,’ said Captain Lal Ariyatilleke, ‘the most difficult part of the campaign was not the fighting, but separating husbands from wives and sons from their mothers.’

Increasingly, all sides in the war have become captives of their own rhetoric. India has long tried to mediate the conflict, even as it was arming and training the Tamil rebels. When the Sri Lankan government launched Operation Liberation, Gandhi began demanding an outright halt to Colombo’s offensive. Last Monday, Sri Lankan forces ended their campaign after taking Point Pedro. But Tamil terrorists ambushed a bus in Eastern province on Tuesday, gunning down 32 passengers, including 29 Buddhist monks. Next day a car bomb exploded outside the 300-year-old army fort in Jaffna, followed by a deadly rebel mortar barrage that left three soldiers dead and 42 wounded. The attacks, coming after Sri Lankan President Junius Jayewardene had just perceived as giving in to New Delhi, left him with little room for further concessions.

At midweek Jayewardene faced yet another demand. Indian officials requested that his government permit a fleet of Indian fishing vessels to deliver relief supplies directly to Jaffna, where more than one-third of Sri Lanka’s 2 million Tamils reside. Jayewardene’s response: No relief was necessary, but if India insisted, its boats could deliver their supplies to Sri Lankan officials for distribution by them. Under no circumstances, he emphasized, would any unauthorized flotilla from India be permitted to violate Sri Lankan territory.

India dispatched the boats anyway, 20 in all, with one of them carrying nearly 100 journalists who had been flown by the government aboard an Indian Airlines jet to the staging area in the port of Rameswaram. Led by the Vikram, an unarmed Indian coast guard vessel, the flotilla set out late Wednesday and reached a point eleven miles from Sri Lankan shores just before dark.

To no one’s surprise, three Sri Lankan frigates were visible on the horizon, already in position to bar the flotilla’s progress. Darkness fell, and rough seas threatened to swamp the small craft. When the frigates radioed the flotilla to halt, the Indian boats turned back to Rameswaram. The fleet’s interdiction prompted a stinging rebuke from New Delhi. Colombo’s intransigence, said an Indian government spokesman, ‘makes it clear that the government of Sri Lanka is determined to continue to deny the people of Jaffna their basic human rights.’

Seeking to maximize its public relations impact, New Delhi then diverted the journalists returning from Rameswaram to an An-32 transports that were already loaded and poised for takeoff in Bangalore. This time Sri Lanka had no means to resist. Its airforce has no jets, and its only antiaircraft guns date to World War II. The government in Colombo was reduced to a verbal riposte, denouncing the violation of its airspace as an ‘outrage’ and an ‘act of cowardice.’

The airdrop dramatized Gandhi’s new assertiveness, and his actions were generally lauded in India. One of the few voices of dissent was an editorial in the Statesman of New Delhi that called the attempted sea lift ‘gunboat diplomacy’ and warned that ‘India appears to have become an active participant in the conflict’.

That was putting it mildly. Gandhi claimed that India’s attempts to mediate a peaceful solution between the Sri Lankan government and the rebels had not succeeded because the government had virtually declared ‘war’ in Jaffna. Combined with an earlier statement that India would no longer remain an ‘indifferent spectator’ to the plight of Tamils, Gandhi’s words seem to convey that further intervention by New Delhi was not only possible but probable.

*****

A Bad-Neighbor Policy

[Rod Nordland, Sudip Mazumdar, Mervyn de Silva: Newsweek, June 15, 1987, pp. 10-11]

Sri Lanka’s bloody four-year civil conflict edged closer to outright war last week. Tamil separatists stopped a busload of Buddhist monks heading to a religious retreat near Kandy. The Hindu Tamils dragged some of the saffron-robed monks off the bus and hacked them to death with long knives; others they shot through the windows, felling them in heaps until 32 had died in all. One 12-year-old novitiate reportedly pleaded for the terrorists to spare his father’s life – and was stabbed to death himself. That outrage was the latest in an alarming escalation of the violence that has already transformed Sri Lanka from an island paradise into a religious and ethnic combat zone. Bad as it was, however, the conflict took an even more serious turn last week when Sri Lanka and its dominant neighbor, India, began drawing perilously close to engaging in military conflict.

Two photos from Newsweek, June 15, 1987

The massacre of the monks came in direct retaliation for recent Sri Lankan efforts to crust the Tamil guerrillas, who are fighting to carve a separate state out of the island’s north and east, to protect them from the ruling Sinhalese Buddhist majority, which makes up 75 percent of the population. Earlier this year, following a host of separatist outrages, Sri Lankan President Junius Jayewardene imposed a blockade on the northern Jaffna peninsula, a Tamil stronghold completely in rebel hands, vowing to ‘wipe out terrorism’. Later he sent 3,000 soldiers and airborne commandos into the area in a punishing offensive against Tamil guerrilla bases.

That caught the attention of many Indians. New Delhi has long allowed India’s 50 million ethnic Tamils to openly support their Tamil cousins in Sri Lanka, which lies only 22 miles across the Palk Strait. As food supplies in Jaffna ran short, and bombing by the Sri Lankans caused many civilian deaths, Indian Tamils agitated for intervention. India then dispatched a flotilla of relief boats with food and medicine said to be intended for civilian victims of the fighting. Early last week the Sri Lankan Navy faced down the Indian flotilla, escorted by at least one Indian gunboat, and forced the ships to turn back. Sri Lanka argued that relief supplies should be delivered through the capital, Colombo. India, the Gandhi government declared, could not remain an ‘indifferent spectator to the plight of the Tamils’.

The next day an Indian Air Force squadron, with five Soviet-made transport planes and a fighter escort of four French-made Mirage jets, set off for Sri Lanka. NEWSWEEK’s Sudip Mazumdar was aboard one of the planes: ‘As we flew across the strait, we could see Sri Lankan naval gunships patrolling the blue-green seas below. Our commander radioed Sri Lankan authorities: ‘Colombo here we come.’ Within the hour, we were above the red-tiled houses and coconut palms of the peninsula, dropping neatly bundled pallets of food supplies by parachute at regular intervals – 25 tons in all.’

The government of Colombo denounced the Indian airdrop as a ‘naked violation’ of Sri Lanka’s sovereignty and territorial integrity and immediately launched a diplomatic offensive of its own. Sri Lanka called for an urgent meeting of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) to help diffuse the tension with India. Sri Lanka appeared already to have several allies in its quarrel with India. China and Pakistan have publicly expressed support for Sri Lanka. Bangladesh and Nepal are also believed to be tilting toward Sri Lanka.

Political Solutions: Both countries stopped just about of being dragged into a shooting war – at least for the moment. Sri Lankan Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasa accused Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi of cynically using the Tamil issue to ‘rally the country’ around ‘a beleaguered government’. India charged that Sri Lanka’s new offensive might result in the genocide of Tamils, and that only political, not military solutions, would solve the conflict. Gandhi has long tried to avoid a direct role in the Sri Lankan conflict – Colombo’s past friendship has had diplomatic value to an India otherwise surrounded by hostile neighbors. But if the Sri Lankans prevail against the Tamil guerrillas, rioting could break out in Tamil Nadu state. Gandhi needs the support of the Tamils politically, particularly in light of the ongoing sectarian strife in India’s life.

President Jayewardene is similarly hamstrung by domestic political considerations. Lately the Tamil guerrillas have scored several other spectacular terrorist attacks. On Good Friday Tamil guerrillas massacred 126 Sinhalese, mostly off-duty servicemen and their families, on a road in the northeastern part of the island. Four days later, on April 21st, a bomb explosion in Colombo’s main bus terminal killed 106 people. These outrages infuriated the Sinhalese and boosted opposition politicians. Militant Buddhist monks have ridiculed the government as ‘impotent’. Jayewardene’s political opponents criticized him sharply. ‘No government since independence has made the people so defenseless,’ taunted former Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike. But if Jayewardene cracks down too severely, India may step up its intervention. And that may be precisely what the separatists are hoping to provoke. Unless all sides manage to get back to the negotiating table, India and Sri Lanka could find it difficult to contain the war to the Jaffna peninsula.

*****

Trespass from the Air

Salamat Ali, Far Eastern Economic Review, June 18, 1987, p. 10-11.

Ignoring Colombo’s protests against what it considered as a challenge to its sovereignty, India air-dropped relief supplies on 4 June over the island state’s Jaffna peninsula which has been ravaged by civil war. The reaction from India’s neighbours in the subcontinent has been uniformly negative, and in Sri Lanka all the Sinhalese-based parties have buried their differences and made common cause against New Delhi.

On the Indian side, all the opposition parties have extended full support to the government’s intervention as an expression of the country’s concern for the beleaguered Tamil minority of Sri Lanka. The already tense ties between the two South Asian neighbours have thus reached an impasse.

Although the way out should be for either side to back off, all signs point to further escalation of the confrontation. Without losing other options, New Delhi appears prepared to conduct further relief air drops, and Colombo is seeking overseas support in organizing its air defences to thwart any Indian moves.

Domestic as well as regional compulsions have forced New Delhi’s hand. Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi came under severe pressure from the south Indian state of Tamil Nadu after Sri Lankan President Junius Jayewardene launched a military offensive declaring a fight to the finish against separatist Tamil guerillas in the northern peninsula, where his writ had not run for the last two years, Madras-based guerilla spokesmen related harrowing accounts of atrocities committed by advancing Sinhalese troops against the Tamil civilians of the Jaffna area.

The four south Indian states, ruled by opposition parties, have traditionally nurtured strong grievances against domination by the north Indians who control New Delhi. Tamil Nadu, which has long been a hot-bed of linguistic separatism, shares a common language, culture and ethnicity with the minority Tamils of Sri Lanka. A failure by New Delhi to react to the plight of the Jaffna Tamils could only be seen by Tamil Nadu as a lack of concern for southern sentiments.

Moreover, India also sees itself as the pre-eminent military and political power in the subcontinent. One of the loudly articulated principles of Indian diplomacy in the region is the opposition to any extra-regional intervention or even anti-Indian influence in any South Asian country. In the current crisis, India was worried about the adverse impact on its regional pre-eminence in the event of its failure to react to the events in the Jaffna peninsula.

Indian officials maintain that Colombo has taken advantage of India’s assurance that it would not intervene militarily and would play a mediatory role in the Sri Lankan conflict. In the bargain, they say, Colombo gained time to force its own military solution. These officials also argue that India had shown patience despite Sri Lankan use of Israeli intelligence services and Pakistani military training which New Delhi considered provocative.

The recent relief operation was obviously not conceived in a hurry. India knew that Sri Lanka would not allow its unarmed boats loaded with supplies to reach Jaffna. So within 24 hours after the aborted sea mission, an air drop was carried out, which indicates contingency planning and a well-considered strategy of graduated response. On 3 June, an official Indian message stated that India “cannot remain an indifferent spectator to the plight of the people of Jaffna.” The air drop conveyed that message rather forcefully. On 2 June India had also announced that its planned relief operation would be an “ongoing process”. Indian spokesmen have refused to confirm if more air drops were in the offing.

The unstated and far more important purpose of the relief supplies in the face of Sri Lankan opposition was to stall Colombo’s military operations. The reaction of other members of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) has been uniformly hostile to India. Maldivian President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, returning from a visit to Bhutan, said that the Indian action was a grave development and his country felt ‘very concerned over it’. Kathmandu deplored the event as did Dhaka and Islamabad.

However, it is not yet clear what action India’s neighbours will take. Colombo has reportedly asked a ‘South Asian’ country’s help in building its air defence. This is taken to mean in New Delhi that Pakistan has been approached. Indian newspapers have reported that Pakistan and China have offered to help Colombo.

Manik de Silva writes from Colombo: Political differences were thrust aside as Sri Lankans closed ranks to denounce India’s intrusion into Sri Lankan airspace to drop supplies into the Jaffna peninsula. All the political parties represented in parliament and most other groups were unequivocal in their condemnation, with Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasa and opposition leader Anura Bandaranaike being particularly outspoken.

Two hours after the air drop, Premadasa, lon the harshest critic of the Indian factor in Colombo’s battle against the separatists, demanded that the SAARC convene an emergency meeting to discuss the Indian action. He followed this up with several public speeches saying that the air drops were probably a rehearsal for an invasion. Bandaranaike said that there had been “an absolute violation of Sri Lanka’s sovereignty which we condemn with all our might.”

Foreign Minister A.C.S. Hameed moved swiftly to loge a protest at the UN. He asked that the president and members of the UN Security Council be kept informed of his protest, which documented the sequence of events. Colombo, however, did not ask for a meeting of the Security Council, confining its diplomatic response to seeking condemnation of the Indian action both in South Asia and in the broader world. The Foreign Ministry sought to project the plight of a small nation being trampled on by a giant neighbour.

It soon became clear that Colombo was not going to pursue Premadasa’s demand for an emergency meeting of the SAARC, whose charter specifically rules out the discussion of all ‘bilateral and contentious’ issues. Colombo also remained undecided on whether Hameed would make a scheduled trip to New Delhi for a SAARC foreign meeting, due to begin on 17 June.

Colombo had always believed that India would stop short of military intervention in the troubled north and the east, despite the pressure put on Gandhi by Tamil Nadu. Colombo noted Gandhi’s earlier statement that India respected Sri Lanka’s unity and integrity and that India’s ‘humanitarian’ action must be viewed in that perspective. Colombo also pointed out that it had wanted to discuss mutually acceptable details of the Indian relief operation, but before that could be done, New Delhi sent in its convoy, which a local newspaper dubbed ‘bum boat diplomacy’.

If India had hoped that the military offensive by Sri Lankan security forces to recapture the Jaffna area would be halted as a result of the air drop, it was a misplaced expectation. The offensive continued and diplomats in Colombo said that New Delhi was obviously unhappy at Sri Lanka’s response to what India called its ‘positive’ signals – an apparent attempt to resume negotiations for solving the ethnic conflict.

Moreover, supporters of the ruling United National Party were among those who organized a 9 June demonstration outside the Indian high commissioner’s residence in Colombo to protest against both the air drop as well the massacre of 32 Buddhist monks a few days earlier.

Compounding the problems for Colombo which had been created by the Indian action, a group of subversives – not connected with the Tamil rebels – carried out two daring raids on 7 June: one on the Sri Lankan Air Force’s main base at Katunayake 32 km north of the capital and the other at the National Defence Academy in Colombo’s southern suburbs. Colombo believes that the raiders belong to the outlawed Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), a group of southern subversives that have become increasingly active in recent months.

Investigators have found that the raiders had used arms taken from an army camp in April. Clearly, the JVP, responsible for a youth insurgency in 1971 when thousands of young people lost their lives, is now busy collecting arms for another putsch. There is an awareness in Colombo that it would be difficult for the government to fight on two flanks – in the north and south – and Premadasa has offered an olive branch to the JVP saying that its proscription will be lifted if it would engage only in legitimate political activity.

*****

The unarmed intervention

[Salamat Ali,. Far Eastern Economic Review, June 18, 1987, p. 10-11]

For the reporters covering Indian moves to break the Sri Lankan blockade of the Jaffna peninsula, it began as a drama on the high seas with the second act moving on to high altitude. The audience – some 100 Indian and foreign correspondents – were flown in a chartered airliner from New Delhi to Madurai, 600 km south of Madras, in the early hours of 2 June.

Madurai, the capital of the ancient Pandian kingdom which often clashed with the princes of Sri Lanka, was to be the media’s base for reporting on the relief shipments leaving for Jaffna from the Rameshwaram fishing port on the southern tip of India. With no official word on what was to follow, the assembled pressmen fed on rumours and gossip, figuring out a possible role for the Indian Navy in the impending operation. The journalists, along with a small team of Indian Red Cross doctors and the leader of the convoy, D.K. Moitra, reached Rameshwaram next morning after travelling by bus and on a train.

It took a whole morning and afternoon for the organisers to acquire 19 fishing boats and load them with supplies. It turned out that the delay was due to some haggling over payment to the boat owners. At 4:30 pm, with naval helicopters and coast guard aircraft circling overhead, the boats set sail. The press and the Red Cross officials were on board an Indian Coast Guard vessel, CGS Vikram, which had been freshly painted white and stripped of its armament, with the crew in civilian clothes.

An Indian Oil and Natural Gas Commission survey ship joined the Vikram as a back-up vessel. All the boats in the convoy flew Red Cross flags. Before sailing the pressmen were told that the operation was a non-military mercy mission to relieve Jaffna’s starving population and the boats would turn back if Sri Lanka objected to their entry into its territorial waters.

Just beyond Indian waters and near Sri Lanka’s Katchathivu island, the Sri Lankan frigate Edithra was sighted. At about 5:15 pm, CGS Vikram received its first message from Edithra asking the vessels not to enter Sri Lankan waters, and negotiations began between the leader of the convoy and Cdr O.T.C. Samarasekra of Edithra. The convoy anchored in Indian waters. At about 8:30 pm, it was announced that the Sri Lankan commander had clear orders to prevent intrusion and that he ‘would do so with all the means at his command.’ The vessels turned back. Reporters began muttering to themselves that India had met its Bay of Pigs.

The press party returned to Madurai the next morning and in the early afternoon boarded its chartered flight back to New Delhi. But in mid-air it was announced that the aircraft was headed for Bangalore, the Southern Command headquarters of the Indian Air Force. It was revealed at Bangalore that five AN32 transporters would air drop supplies over Jaffna.

Only 35 of the reporters, including this correspondent, could be accommodated in the transporters which took off at 4 pm and were escorted by four Mirage 2000 aircraft. The Indian aircraft attempted radio contact with Colombo, but were ignored. Descending to about 1,500 ft between Jaffna town and its airport, the AN32s dropped their relief cargo at about 5 pm. The air drop, called Operation Flower Garland, was over in two hours and covered 1,000 km.

*****

More in the War of Words: Colombo decries the airlift

[Anon: Time, June 22, 1987, p. 19]

Bearing signs reading BULLY BOY INDIA, 3,000 Sri Lankans marched through the streets of Colombo last week, led by a group of saffron-robed Buddhist monks. Rhythmic chants droned through loudspeakers mounted atop a sound truck decorated with large brass figures of the Buddha and his disciples. When the crowd arrived at the residence of India’s High Commissioner, J.N. Dixit, one of the monks read a statement accusing the Indian government of committing a ‘tremendous national affront’ against the people of Sri Lanka.

India’s transgression, as the protestors saw it, was violating Sri Lankan airspace a week earlier to parachute relief supplies to Tamil civilians in the war-torn Jaffna peninsula. Few Sri Lankans doubted that what New Delhi described as ‘humanitarian aid’ amounted to yet another show of support for separatist Guerrillas seeking an independent homeland for Sri Lanka’s Tamil minority.

President Junius Jayewardene attempted to seize the high ground on the intervention issue, declaring that Sri Lanka would not resist an Indian invasion of his country, which lies only 22 miles off the southeastern tip of India. In doing so, he seemed to be trying to shame New Delhi into dropping possible plans for military action. ‘The paths of violence, of bullying,’ said Jayewardene, ‘is not the political heritage India inherited from Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru.’

The latest confrontation between the two neighbors began late last month with Operation Liberation, a Sri Lankan offensive aimed at clearing the Jaffna peninsula of guerrilla strongholds and landing areas for supplies ferried over from India. The insurgents charged that 1,000 civilians were killed by government forces during the fighting. Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi added his voice to the protest, accusing the Sri Lankan military of ‘carpet bombing’ civilian areas. Partly in response to Indian demands, Jayewardene last week put the offensive on hold.

Almost overlooked in the controversy was the fact that the Jayewardene government had scored a military victory over the rebels. Sri Lankan troops had forced the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, the main guerrilla group, to retreat from an area around Valvedditturai where the insurgents enjoyed solid support. The rebels – and their supporters in India – also suffered a public relations setback when reporters visited the combat zone and found little evidence of carpet bombing or civilian starvation. The civilian death toll turned out to be close to the Sri Lankan government’s claim of 48, a fraction of the total cited by Gandhi and the Tamil exiles. However, when TIME New Delhi Bureau Chief Ross H. Munro broke away from a government-organized press tour, he came upon a scorched area near a Hindu temple in Alvai, west of Point Pedro. The temple had been designated an official civilian sanctuary, Munroe was told but when planes and helicopters circled low over Alvai on the first day of the offensive late last month, many inside the temple panicked and ran into the open. According to witnesses, at least five died and 15 suffered burns when an incendiary device was dropped into their midst, 200 yards from the temple, by a Sri Lankan airforce plane whose crew might have mistaken those fleeing for Tigers.

Last week’s continuing bloodshed stemmed mainly from Tamil ambushes. At least twelve civilians were slain when a land mine blew up under a van near the port of Trincomalee. Two miles west of Point Pedro, in an area supposedly under army control, another rebel mine ripped through a military convoy that was carrying 60 Tamil civilian detainees back to their homes. The toll: ten Tamils dead, five wounded.

*****

Sri Lanka Options.

[Anon: Asiaweek, June 28, 1987]

When Sri Lanka’s Foreign Minister Shahul Hameed flew to New Delhi June 16, Indian High Commissioner Jotindra Nath Dixit was among the dignitaries who saw him off at Colombo’s international airport. For the past few weeks, Dixit has been a frequent visitor to Hameed’s red-carpeted office, a few blocks from the Indian High Commission. Relations between their countries have been strained since Colombo launched a military offensive in May against Tamil separatists in Sri Lanka’s strife-torn Jaffna peninsula. Tensions grew after India’s June 4 relief airdrop in Jaffna, made against Colombo’s wishes.

Smarting from what it termed a flagrant violation of its territorial integrity, Sri Lanka indicated it would boycott a meeting of foreign ministers of countries belonging to the South Asian Association of Regional Cooperation. Hameed’s departure for the SAARC conference, held this year in the lushly green Indian capital, was a reversal of that decision. ‘We took all the factors into consideration and assessed them very carefully, particularly the concern expressed by other member states and their desire we should participate.’, declared the Sri Lankan minister. Bowing to pressure from SAARC members, Colombo had earlier agreed to send representatives to conference committee meetings.

According to Dixit, the relief airdrop was part of a ‘graduated scale of options’ that were available to the Indian government to feed civilians ‘starved’ by Colombo’s fuel & food blockade clamped on Jaffna since January. ‘Consider the speed with which India reacted to the turning back of its aid flotilla [on June 3],’ said Dixit. ‘That was option one and when the response to that option was negative, option two was carried out.’ Analysts in Colombo believe India is planning a third, more formidable, option: large scale armed intervention. A military intelligence official in Colombo told Asiaweek that they had ‘confirmed information’ of a heavy troop build-up in India’s southern Tamil Nadu state, barely 90 km away from Sri Lanka across the Palk Strait.

He claimed that the Indian Army had rushed in men and equipment from its Central Command to beef up its Southern Command. An abandoned military airfield near the south Indian city of Rameswaram had also been renovated and troop transporter aircraft stationed there, he said. Indian Navy sources in New Delhi revealed that more than a dozen vessels had been mustered for a possible naval intervention in Sri Lanka.

Tiny Sri Lanka is aware that it cannot defend itself militarily against its giant neighbour. Colombo, therefore, has been lobbying for support from other regional powers. Sri Lanka’s Education Minister Rail Wickramasingha flew to Peking recently with a personal message from President Junius Jayewardene to top Chinese leaders. On his return journey, he spent two days in Islamabad where he met Pakistan strongman Zia-ul Haq. National Security Minister Lalith Athulathmudali, en route home from the US, also stopped over in Islamabad where he met Zia and other top Pakistani leaders.

*****