RAW’s malformed Baby that lived for 9 months

by Sachi Sri Kantha, June 10, 2024

As a chronicler of Eelam history of the 20th century, I had been highlighting issues and items that demands a record and focus. One such item was the brief existence of Tamil National Army (TNA), a malformed baby of India’s RAW with Rajiv Gandhi’s imprimatur, 35 years ago. This TNA appeared in the political lexicon of Sri Lanka, prior to another TNA (i.e. Tamil National Alliance). Pundits from India– the likes of Subramanian Swamy, Narasimhan Ram, Malini Parthasarathy, Col. R. Hariharan, P.K. Balachandran and B. Raman – have conveniently ignored this TNA that came into existence in 1989. To his credit, Narayan Swamy provides little detail on the origin of TNA, in his 1994/1996 book ‘Tigers of Lanka’, as a consequence of a meeting by A. Varadaraja Perumal (the then Chief Minister of the newly established North-East Province, during 1988) and Rajiv Gandhi in July 1989. The prime irritant to Rajiv was the newly elected Sri Lankan president Premadasa’s grandstanding on ‘sending back the IPKF’ issue.

Annamalai Varadaraja Perumal

Here is a brief synopsis of this, RAW’s malformed baby that ‘lived’ pecariously for 9 months.

‘mother’: India’s RAW mandarins

Purported ‘father’: Rajiv Gandhi

Cause of birth: (1) to be an irritant to the newly elected Sri Lankan president R. Premadasa, who (assumed office in Jan 1989) and had opposed the Rajiv-Jayewardene Accord of July 1987. (2) to support the puppet regime of EPRLF government of Varadaraja Perumal, installed in the northern and eastern provinces of Sri Lanka.

Active life phase: ~ 9 months, from July 1989 to March 1990.

Cadre: ~ 2,700 ill-trained conscripts among Eelam Tamils.

Wet nurses: quadripartite Tamil National Council (comprising of EPRLF, ENDLF, TELO and PLOTE)

Date of first encounter with Tamil Tigers: Nov 5, 1989.

Projected leader: George Thambirajah

Cause of death: mauled badly by Tamil Tigers (aka, LTTE)

Reason: orphaned by ‘mother’ and ‘purported father’, after Congress Party relinquishing its claim to governance of India on Nov 28, 1989 following the general election (Nov 22-26, 1989).

Escape route of those who escaped mauling: ~1,600 given ‘refuge in Orissa state by V.P. Singh administration, after being rejected by M. Karunanidhi (then elected DMK Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu).

A collection of 27 TNA-related references, which I was able to gather, is given below in chronological order. These have been collected from the Economist, Asiaweek (Hongkong), Tamil Times (London) and Lanka Guardian (Colombo) magazines. Excluding a few exceptions, most reporters were not identified by name. Thus, their bias(es) against the LTTE cannot be verified. Nevertheless, readers can grasp the atrocities committed by this ‘slipshod militia’ (tagged as such by Time’s reporter Lisa Beyer) given birth by RAW officials and Rajiv Gandhi combine, during its brief life span of less than nine months. Among these 27 references, only two items offer noticeable details about TNA appeared in the Asiaweek of November 17, 1989 (without an author byline) and in Frontline of Feb 16, 1990 (by Thomas Abraham), reprinted in the Tamil Times, March 1990. Even the TNA commander(s) were NOT named!

Among the two, Abraham’s report to the Frontline magazine (of the Hindu group) is more interesting and rather devious in that RAW has NOT been mentioned even once. It appears to me that Either Abraham or the editorial desk of ‘Frontline’ magazine tactfully substituted the word ‘India’ to ‘RAW’. I remember reading a non-confirmed report in the net few years ago that this Abraham guy had interactions with RAW cubicle (located in the Indian high commission) in Colombo during his tenure. He served as the ‘Hindu’ correspondent from Colombo, from 1988 to 1992. David Housego’s report, originally published in Financial Times (London) and republished in the Lanka Guardian, identified the deceased leader of TNA as George Thambirajah.

Though I had been critical about the writings of Rohan Gunaratna (Sri Lanka’s terrorism expert), I credit him for authoring a 500 page book ‘Indian Intervention in Sri Lanka – The Role of India’s Intelligence Agencies’ in 1993, long before he joined the global circuit of terrorism industry. Among the 14 chapters, Gunaratna had allocated one chapter to describe the activities of TNA. It had the title ‘India’s proxy war: Rise and Fall of the TNA’ (pp. 355-402). Strangely, this book’s publisher is identified as ‘South Asian Network on Conflict Research’, with a Colombo post office box number 745! I wonder whether this ‘network’ is still extant.

As per the question of ‘what happened to the surrendered TNA conscripts’, Adele Balasingham had observed in her 2001 book, ‘Only the hard core EPRLF cadres resisted [surrender]. All those who had surrendered were immediately released to their relieved parents in the Eastern districts. Some of those who surrendered joined the LTTE”.

Bibliography on the short life of TNA

Anon: Tigers protest abductions. Lanka Guardian, July 1, 1989, p.6.

Anon: Leaving it to the Tamils. Asiaweek, Oct 20, 1989, p. 32.

Sri Lanka correspondent: A catastrophe in the making. Economist, Nov 11, 1989, pp.41- 42.

Anon: Once again, Tamil vs Tamil. Asiaweek, Nov 17, 1989, pp. 36-37.

Mervyn de Silva: Premadasa presidency; the moving target. Lanka Guardian, Dec 1, 1989, pp. 3-4.

Anon: Won’t walk into trap – President. Lanka Guardian, Dec 1, 1989, p. 5.

Anon: Civil war, warns Speaker. Lanka Guardian, Dec 1, 1989, p. 5

Rita Sebastian: The North East powder keg. Tamil Times, Dec 15, 1989, p. 4

Anon: Violence spreads in Tamil areas. Tamil Times, Dec 15, 1989, p.5

Anon: Lankan troops deployed in Batticaloa. Tamil Times, Dec 15, 1989, p. 6

Anon: TNA cadres surrender. Tamil Times, Dec 15, 1989, p.6

Anon: New rounds of bloodshed. Asiaweek, Jan 5, 1990, p. 16.

Anon: Blood feuds and vigilantism. Time, Jan 8, 1990, p. 27.

Anon: LTTE forms political party. Tamil Times, Jan 15, 1990, p. 7

Anon: Sri Lanka loses count of thousands killed. Tamil Times, Jan 15, 1990, p.9 (a reprint from The Indian Post, Bombay, Dec 30, 1989).

Anon; News round-up. Tamil Times, Jan 15, 1990, p. 12

Sivanayagam: The Tamil struggle – This is no time to fall behind. Tamil Times, Jan 15, 1990, pp. 15-16.

Anon: North-East PC Members killed. Tamil Times, Jan 15, 1990, p. 18.

Colombo correspondent: Tigers on the prowl again. Economist, Jan 20, 1990, p. 38.

David Housego: A funeral in Trinco. Lanka Guardian, Feb 1, 1990, pp. 14-15 (a reprint from Financial Times, London).

Saybhan Samat: The Muslim Factor. Lanka Guardian, Feb 1, 1990, p. 15

Anon: Jaffna’s orphans of war. Asiaweek, Feb 9, 1990, p. 27.

Lisa Beyer: Back roar the Tigers. Time, Feb 12, 1990, pp. 32-33.

Rita Sebastian: Taming of the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress? Tamil Times, Feb 15, 1990, pp. 6-7.

Thomas Abraham: A failed strategy. Tamil Times, Mar 1990, pp. 17-18. (a reprint from Frontline, Madras, Feb 16, 1990).

Anon: Indian’s exit, Tigers return. Asiaweek, Mar 30, 1990, p. 26.

Lisa Beyer: No tears here. Time, Apr 2, 1990, pp. 8-9.

Details pertaining to TNA, as they had appeared in these items are reproduced below verbatim, devoid of any addition or deletion.

Anon: Tigers protest abductions. Lanka Guardian, July 1, 1989, p.6.

Northern and Eastern Tamil youths are being abducted or conscription into the Citizens Volunteer Force of the North-East Provincial Council, the Tigers (LTTE) have complained. They have accused the EPRLF of doing this with the help of the Indian army. EROS, club mate of the LTTE, joined the Tigers in making the accusation. They said that 4,505 youths had been abducted; 4,000 had been snatched in the Batticaloa district, 105 had been taken off a train at Vavuniya, and 400 were being kept at the Alles Garden IPKF camp in Trincomalee.

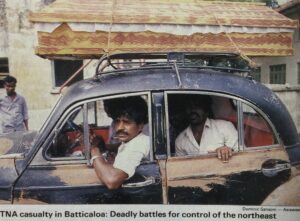

Transporting a TNA casualty in Batticaloa (source – Asiaweek magazine, Jan 5, 1990)

Anon: Leaving it to the Tamils. Asiaweek, Oct 20, 1989, p. 32.

Provincial Chief Minister Varatharaja Perumal’s ‘army’ is the Citizen Volunteer Force of some 2,700 inexperienced youths.

Sri Lanka correspondent: A catastrophe in the making. Economist, Nov 11, 1989, p. 41-42.

Exit the Indian peacekeeping force from Sri Lanka, enter the Tamil National Army. The what? Despite its official-sounding title the ‘army’ is a private group that hopes to take over the policing of the Tamil areas in the north and east of the island when the Indians withdraw their troops. It seems highly unlikely that this is what will happen. Instead, poor, battered Sri Lanka will have acquired what it least needs; yet another armed band.

The Sri Lankan government is appalled by the new group. As in the past, it can forsee a catastrophe; as in the past, it is too weak to prevent it. In September it got the Indians to agree to withdraw stage by stage, with the last of their troops, which now number some 36,000, due out by the end of the year. It expressed confidence that the police and the Sri Lankan army would between them provide security for the local people when the Indians left.

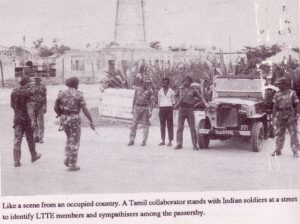

At the end of October the Indians pulled out of the eastern district of Amparai. But before the police had a chance to pound their first beat, the Tamil National Army had taken over 12 of the camps vacated by India. According to the Sri Lankan government’s intelligence agency, the Tamil National Army’s men arrived at the camps in Indian lorries and helicopters. They had been trained by the Indians and carried Indian weapons. The people of Amparai were ordered to stop at Tamil National Army roadblocks, to observe its curfews and generally to accept that it was in charge of law and order in the district. Clearly, anyone in Amparai who thought army-of-occupation days were over was mistaken.

Equally clearly, the Indians have decided that Sri Lanka’s government is incapable of protecting the Tamils – in particular those who are members of the North-Eastern Provincial Council. The council is dominated by three Tamil groups which laid down their arms when the Indians arrived and agreed to pursue their aims in a peaceful way. They have abandoned their original demand for a separate Tamil state in Sri Lanka; in return, the council has been granted a large degree of local autonomy. Their main enemy is the feared Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. The Tigers continue to demand self-rule and say the other Tamil groups are collaborators with India.

Worried about their fate after the Indians leave, the three groups have been conscripting young Tamil men throughout the north and east to raise the 30,000-strong Tamil National Army. Though India is not formally backing this group, it is believed to be supported by the Indian intelligence agency known as RAW (the Research and Analysis Wing). RAW is keen not only to protect the Tamils who cooperated with India, but also to stop the Tigers from lording it over the north-east again. India has lost more than 1,100 men fighting the Tigers.

The Sri Lankan government has promised that it will recruit 20,000 Tamils into its army to ensure that security is maintained even-handedly. But many in the provincial council think this is an empty promise. The Tigers have been having peace talks with the government in Colombo. One thing the Tigers want from these talks is a free hand in the north-east once the Indians have left.

The prospect in the battle-scarred north and east is that the region could die a Lebanon-like death. The first wound was inflicted on November 5th. A Tiger unit attacked two camps of the Tamil National Army in Amparai, killing around 50 people. The Tigers drove away with two trailerloads of captured weapons. The Sri Lankan army arrived too late to stop the killings.

Anon: Once again, Tamil vs Tamil. Asiaweek, Nov 17, 1989, pp. 36-37.

A new name has entered Sri Lanka’s lexicon of strife: the Tamil National Army (TNA). Its debut was inglorious and bloody, vindicating predictions of internecine carnage in the island’s Tamil community the moment Indian peacekeeping troops withdrew. That pullout, urged by Colombo in partial answer to the depredations of both Tamil and Sinhalese extremists, is now underway and due for completion by year’s end. On November 5, the dominant Tamil guerrilla group, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, clashed with the new force in eastern Ampara district. Dozens were killed, and a new chapter opened in the sorry history of Sri Lanka’s ethnic tribulations.

The TNA has been cobbled together by four of the Tigers’ rival groups, headed by the India-backed administrators of the Northeastern Province, the Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front. All were spawned in the struggle for Tamil rights waged against the Sri Lankan government in the early 1980s, but the Tigers’ insistence on an independent Tamil state soon pitted them against those prepared to accept partial autonomy. Among those mauled into submission by the Tigers were the Tamil Eelam Liberation Organisation, the Eelam National Democratic Liberation Front, and the People’s Liberation Organisation of Tamil Eelam. Now they have re-emerged, united with the Front in a quadripartite Tamil National Council. The council sponsors the new army, which suffered heavy casualties in its first encounter with the Tigers.

The TNA has no sanction from the Sri Lankan government, which is strongly opposed to the freebooting militias that play havoc with national security. But the EPRLF’s legal Civilian Volunteer Force, a paramilitary supplement to the national police, consists largely of inexperienced youths and is no match for the Tigers (‘They know only to shoot and salute’, says one senior police officer.) ‘We do not believe that any Tamil national army exists.’ Says Foreign Minister Ranjan Wijeratne, who is also minister of state for defence. ‘But if they do they are strongly advised to lay down their arms.’ The government, he added, would destroy ‘illegal groups…of whatever colouring.’

The TNA has no sanction from the Sri Lankan government, which is strongly opposed to the freebooting militias that play havoc with national security. But the EPRLF’s legal Civilian Volunteer Force, a paramilitary supplement to the national police, consists largely of inexperienced youths and is no match for the Tigers (‘They know only to shoot and salute’, says one senior police officer.) ‘We do not believe that any Tamil national army exists.’ Says Foreign Minister Ranjan Wijeratne, who is also minister of state for defence. ‘But if they do they are strongly advised to lay down their arms.’ The government, he added, would destroy ‘illegal groups…of whatever colouring.’

It was a stern warning, but the Tamil National Council sees the Tigers as the greater threat. Militarily outclassed by the Indian peacekeeping force, the Tigers had broached talks with Colombo in April. They argued for an Indian withdrawal and called for disbanding of the ‘quislings’ – Tigerspeak for the EPRLF. With Indian troops going home, the Council is banking on the TNA to keep the Tigers at bay.

Squads of the new militia have moved into barracks recently vacated by Indian troops in Ampara district. They are committed, says one commander, to ‘keeping the civil administration in the north and east functioning. Any threat to that will be met with force by us.’ The militia was nearly 2,000 strong, he said, and deployed in the Tamil villages of the northeastern coast. ‘The Tigers are the biggest threat to peace in the Tamil areas. They’re still flaunting the fact that they want a separate state for the Tamil people while talking to the Sri Lankan government.’

The Tigers dismiss the TNA as an ‘army of cronies’, and accuse the Indian secret service of being behind it. The ‘recalcitrant organisations’ of the Council are ‘creating a force to destroy the Tamil people and their independence’ read a Tigers statement issued in London, which also challenged the Council to the test of elections. That must have seemed far-fetched to the citizens of Ampara district, who now fear being caught in the crossfire of a heightened war. ‘We had some sort of peace with the Indians here’, said a businessman in Akkaraipattu, where one of the weekend’s clashes took place. ‘Now there are signs of heavy battles ahead.’

Much will depend on how Colombo deals with the changing Tamil equation. The TNA is sponsored by groups which are prepared to accede to the unitary state propounded by the administration of President Ranasinghe Premadasa. The Tigers, however, remain committed to secession, despite having ‘declared peace with the Sri Lankan government and the Sinhalese people.’ Notes one analyst: ‘The government has given tacit support to the LTTE and denounced the TNA. So whom will the Sri Lanka army support?’ Said one police officer in Akkaraipattu, when asked what would happen if the Tigers and the TNA waged war there; ‘We’ll have to sit back and watch’.

The TNA commander Asiaweek spoke to pledged that his men would do ‘everything possible to avoid confrontation with government security forces. But ‘the LTTE will not be able to last long against us, if they want to make trouble.’ The EPRLF’s Varatharaja Perumal, chief minister of the Northeastern Province, is in no doubt about what’s to come. ‘The Tigers’, he told a Colombo press conference, ‘are preparing for war’. And they have found a new enemy against which to wage it.

Mervyn de Silva: Premadasa presidency; the moving target. Lanka Guardian, Dec 1, 1989, pp. 3-4. [note: word in bold letters, as in the original.]

The war, a new war, suddenly erupted in the East. A new ‘army’ too – the Tamil National Army of the EPRLF, ENDLF and TELO, trained in Indian camps and equipped by the IPKF. The TNA is certainly not the Civilian Volunteer Force (CVF) which the North-East Provincial Council and its Chief minister Mr Varatharaja Perumal was empowered to establish so that it could undertake law-and-order tasks once the IPKF pulls out of the island. The deadline, not too rigid, was Dec 31, and it looked that time was running out for the N-E Council and its Chief Minister. The LTTE made that clear in a characteristically brilliant and murderous attack on two new TNA camps in Batticaloa. It massacred some 36 TNA cadres, and kidnapped over 100, and drove off with a huge haul of modern arms, Indian and Soviet made.

Event in the East, and the general pattern of developments there suggest a ‘mix’ of the two – build up an EPRLF-ENDLF=TELO controlled ‘army’ and destablise the East for possible political gains. E.g; scare the Sinhalese away from Amparai, the district from which the IPKF pulled out. The Muslims were another target, more Muslims and Muslim policemen dying in the TNA rocket attacks on the police stations than any other community. Together, the Muslims and the Sinhalese can decide the crucial referendum on the extension of the present North-East merger.

As the JVP campaign reached its peak, an eruption of armed violence in the East, with the possibility of communal clashes, would totally destablise the Premadasa regime, an Indian objective too. The LTTE and some influential sections of UNP believe it is all an Indian plot hatched by RAW.

Anon: Won’t walk into trap – President. Lanka Guardian, Dec 1, 1989, p. 5.

President Premadasa commenting on the situation in the Eastern Province said that Sri Lanka would be cautious not to fall prey to any deliberate campaign of provocation to create a situation to prolong the stay of the IPKF in Sri Lanka. The President was speaking to members of parliament at the Government Parlimentary Group meeting – the members called for strong action against the illegal army formed by the North Eastern provincial council Chief Minister, Varatharaja Perumal, in collaboration with the IPKF.

The Government came to know that an army was being raised in the North-East Provinces without any legal sanction. When the IPKF Commander was asked whether the IPKF was training any army in the province the Commander admitted that this was so. The President said that he told the Commander that it was wrong for the IPKF to train an illegal army.

The violence unleashed by this illegal army in the East is a deliberate attempt to provoke the Sri Lankan security forces into a confrontation.

Anon: Civil war, warns Speaker. Lanka Guardian, Dec 1, 1989, p. 5

Mr. Ashraff, leader of the SLMC, made a statement on the situation in the Ampara district. The TNA attacked a police post, segregated the Muslim policemen and killed 43 of them, he said. Mr Ashraff described the attack as an absolute betrayal of the trust that the Muslims had placed in the provincial government. The situation, he said, was very grave.

Rita Sebastian: The North East powder keg. Tamil Times, Dec 15, 1989, p. 4

Things came to a head in early November with Tiger attacks, on what they described as two camps of the illegal Tamil National Army. This was followed in mid-November by attacks on four Sri Lankan police stations in the Amparai district by the Tamil National Army in which forty three Muslim Citizens Volunteer Force personnel were massacred by TNA personnel.

Although members of the Tamil National Army are said to have moved out of Amparai, they are making their presence felt in other areas. Even given the fact that quite a number of them were forcibly conscripted EPRLF, TELO and ENDLF cadres who form the bulk of the Tamil militia who will be determined to see that the Tigers don’t have their way.

Muslim politicians accuse the EPRLF of using the Muslims as a buffer in their battle with the Tigers.

Anon: Violence spreads in Tamil areas. Tamil Times, Dec 15, 1989, p.5

The Tamil National Army which has been formed by the EPRLF, ENDLF and TELO have been seeking to retain control of the areas vacated by the IPKF, and the LTTE is making a determined bid to drive out their rivals and the Tamil National Army and regain gradual control. In the midst of this internecine confrontation, the Sri Lankan armed forces including the Special Task Force are being brought into the Tamil areas and are themselves engaged in violent clashes with the Tamil National Army.

Upon the withdrawal of the IPKF from the Amparai district at the beginning of November, the TNA set up camps and the Citizens Volunteer Force (CVP) of the Provincial council began undertaking security functions. The LTTE, in its declared resolve to drive out the illegal TNA mounted simultaneous attacks on the camps of their rivals. The Sri Lankan government took the opportunity to introduce its forces to ‘protect the people of the district’. Having withdrawn from the area, on 17 November the TNA attacked four police stations at Sammanthurai, Chavalakadai, Kalmunai and Akkaraipattu in the course of which an estimated one hundred persons died on both sides, including 43 reserve CVF personnel at the Karativu police station, all Muslims. The Sri Lankan Muslim Congress has accused the TNA of having allowed the Tamil CVF men to escape and massacred the Muslims, an act which the SLMC described as an absolute betrayal of the confidence reposed in the Provincial government by the Muslim population. To dislodge the TNA, the government rushed in additional reinforcements and helicopter gunships were used to fire rockets. Hundreds of civilian casualties were reported.

The IPKF completed their withdrawal from the Batticaloa district by November 30 and ever since there have been frequent armed clashes between the contingents of the LTTE and the TNA, the former seeking to establish military dominance in the area as they had already achieved in the Amparai district. The EPRLF and its allies have accused the Sri Lankan government and its security forces of aiding and abetting the LTTE. At the same time they have also accused the LTTE of enabling the Sri Lankan security forces to re-establish themselves in Tamil areas.

‘LTTE cadres in separate groups are reported to be at the heels of the retreating illegal Tamil National Army whose cadres in the majority have been pushed further away from the environs of Batticaloa towards the direction of Trincomalee. LTTE cadres in considerable numbers have been seen in the areas covering Kalawanchikudi dogging the footsteps of the retreating TNA as the IPKF withdraws more men…The LTTE cadres are believed to have come from Thirukoil, Pottuvil, Amparai and Nawagamgamuwa’, The Island of 5 December reported.

On 3 December two truckloads of Sri Lankan soldiers near Vavuniya in northern Sri Lanka were ambushed by Tamil militants killing seventeen soldiers who were returning to their camp after home leave. The Colombo government’s accusation that the TNA was responsible for this attack has been rejected by EPRLF sources. The Sri Lanka forces were reported to have engaged in retaliatory attacks.

Fighting was reported to be continuing between the LTTE and the TNA contingents on 4 and 5 December in the jungles of Unnachchi, Kiran, Punnikulam and Kalawanchikudy. On the afternoon of 5 December, TNA personnel mounted an attack on the Batticaloa police station firing mortars in an effort to storm the police station complex. Elite commandos and armed forces backed by helicopter gunships were reported to have repulsed the six-hour long attack. According to SP Batticaloa, G. Thenabadu, the police assisted by the elite STF, army and air force took control of the security situation after ground and air attacks directed at TNA positions dislodged them and that the Sri Lankan forces had inflicted heavy casualties and losses on the TNA. There were dozens of civilian casualties resulting from these incidents and civilian administration, transport and communications had been disrupted in Batticaloa.

The LTTE on 8 December issued an ultimatum to the cadres of the Tamil National Army to surrender within 24 hours through posters in the Northeast.

Anon: Lankan troops deployed in Batticaloa. Tamil Times, Dec 15, 1989, p. 6

Minister of State for Defence Ranjan Wijeratne, visited Batticaloa on 2 December and ordered the army to deploy troops in the area to disarm the TNA. The minister’s visit followed the IPKF’s withdrawal from the district and came at a time when about 3,000 TNA cadres were reportedly trapped in the area by the LTTE.

The sources said Mr Wijeratne met senior security officials in Batticaloa and was briefed on the situation in the area. They said he was informed about the TNA efforts to dominate the area and the difficulty the police faced in maintaining law and order. They said TNA cadres deployed in two or three camps in the district appeared to be trapped since they could neither go north to Trincomalee nor south to Kalmunai because of LTTE concentrations in Poonani and near Kalmunai.

Anon: TNA cadres surrender. Tamil Times, Dec 15, 1989, p.6

At least 484 cadres of the Tamil National Army have surrendered to the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and the Sri Lankan army. Most of them had surrendered with arms and ammunition claimed to be used by the IPKF.

Of the 484, 400 surrendered to the LTTE in the east, LTTE political chief Anton Balasingham said. Mr Balasingham who returned to Colombo after visiting some areas in the Ampara-Batticaloa sector on 28 November said that 300 surrendered to the LTTE in the Trincomalee district where fighting erupted between the Tigers and IPKF backed TNA men at Sambalthivu and Koviladi. The rest surrendered in Batticaloa.

In Welioya, eighty four TNA cadres surrendered to the Sri Lankan army, defence secretary general Sepala Attygalle said. He said that 84 men of the TNA surrendered to Sri Lankan army officers after walking over twenty miles through jungles.

Anon: New rounds of bloodshed. Asiaweek, Jan 5, 1990, p. 16.

Back in the Tamil northeast, LTTE fighters were once again locked in deadly battles with the rival Tamil National Army for control of districts being vacated by New Delhi’s enforcers. The pro-Indian Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front (EPRLF), which backs the recently formed TNA, is nominally in power in the north-east after winning 1988 polls there which the Tigers boycotted.

The inter-Tamil was resumed in late November as Indian columns began pulling out from Batticaloa and Ampara in the east and Vavuniya, Mullaitivu and Mannar in the north. The Tigers easily gained control of Ampara but suffered heavy casualties in Batticaloa before finally routing the TNA. Heavy fighting was still going on in other areas. ‘The north and east will be awash with blood as the Tigers are imposing their hegemony on the people’, charged the EPRLF’s Varatharaja Perumal, the region’s chief minister. He condemned the government for not stopping the carnage. Colombo sent in army troops to Batticaloa – but ordered them not to intervene. ‘We don’t want to be accused of killing Tamils,’ explained Wijeratne.

But the foreign minister hotly denied LTTE claims that Colombo has given it ‘the task of disarming the TNA’. Snapped he: ‘We want to disarm both parties.’ Observers say Colombo will have to call fresh polls now that Perumal’s administration has collapsed in at least two districts.

Another headache for Colombo is the Indian factor. Wijeratne has accused New Delhi of arming the TNA. Its poor military showing is reportedly one reason for India’s unwillingness to leave.

The Sri Lankan military announced Dec. 26 that 150 TNA cadres had surrendered at least a hundred of their heavy weapons. And New Delhi has called on Tamil Nadu chief minister Muthuvel Karunanidhi to ‘exert his influence’ on his Sri Lankan brethren.

Anon: Blood feuds and vigilantism. Time, Jan 8, 1990, p. 27.

The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam the most feared of Sri Lanka’s militant Tamil groups, have formally given up their fight against the central government in Colombo. But the Tigers have other prey, particularly the Tamil National Army, an illegal militia raised by the rival Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front. Last week the Tigers caught and killed at least 75 of the TNA fighters.

Anon: LTTE forms political party. Tamil Times, Jan 15, 1990, p. 7.

At a press conference in Colombo on 20 December, LTT’s chief spokesman Anton Balasingam…denied reports that the LTTE and the Sri Lankan army had jointly attacked the so-called Tamil National Army, military wing of the rival Eelam People’s Revolutionary Front, in the eastern Amparai and Batticaloa districts, but admitted that the Sri Lankan forces were aware of impending attacks. ‘We have advised the Sri Lankan government not to allow its forces to launch offensive operations against the TNA, as that would be used for prolonging the stay of the IPKF in the island’, he said.

Mr Balasingham said that the LTTE would continue to fight the TNA and said the Tigers were involved in a struggle to disarm the TNA, and they had already succeeded in Amparai and Batticaloa and said that the ceasefire that the LTTE had declared did not apply to the TNA.

Asked why he thought it proper that the LTTE should carry arms while the TNA could not, Mr Balasingham said that it was not possible to equate the LTTE with the Tamil National Army. The LTTE had been inexistence for 17 years and was recognized as a force fighting for national liberation. The TNA on the other hand had been hurriedly created and armed by India and was not a genuine force.

Anon: Sri Lanka loses count of thousands killed. Tamil Times, Jan 15, 1990, p.9 (a reprint from The Indian Post, Bombay, Dec 30, 1989).

While the LTTE and the Sri Lankan government say the TNA was trained and armed by the IPKF, India has categorically denied the allegation and Perumal has argued that the TNA was actually a name given by the Sri Lankan government to volunteers recruited and trained for absorption into the legally constituted Citizens Vounteer Force (CVF). The CVF was raised much before its recognition by the Sri Lankan government. Perumal said, complaining that the Colombo administration backed out of its commitment to raise the CVF strength to 7,000 from the recognized strength of 2,000.

Anon; News round-up. Tamil Times, Jan 15, 1990, p. 12

Many members of the Tamil National Army sponsored by the EPRLF and its allies are said to have deserted and found their way to Colombo from the North-East after either throwing away or selling their weapons. At a press conference in Colombo on 20 December, the Secretary of the PFLT, the political wing of the LTTE said that the LTTE would keep all weapons they had captured from the TNA and they would not be handed over to the government.

Forty five men of the Tamil National Army who were retreating after a three day fierce battle with the LTTE were killed on 25 December at Aralagamwila in the Polannaruwa district; 176 others surrendered with their weapons to the Singha Regiment camped at Aralagamwila, and the captured weapons included 89 T-56 assault rifles, four Chinese light machine guns, 20 hand grenades and over 10,000 rounds of T-56 ammunition.

Sivanayagam: The Tamil struggle – This is no time to fall behind. Tamil Times, Jan 15, 1990, pp. 15-16

The Citizens Volunteer Force (CVF) and the so-called Tamil National Army (TNA) are losing ground wherever the IPKF has been withdrawing. Teenage Tamil youths conscripted forcibly are either being sent to slaughter or are surrendering. I am told that in the very first week of December ’89, at least 200 Tamil youths had landed at Amsterdam airport with false passports and visas, having each paid Rs 1 lakh and twenty thousand in Sri Lankan rupees in their act of fleeing, not from the oppression of any government or armed forces, but from what they had told the Dutch officials, from the ‘drunken devilry’ (they used the Tamil word ‘veriattam’) of ‘our own groups’ – not a happy advertisement to the entire Tamil cause! Adding to the dismal picture are bands of other youths crossing over to Tamil Nadu, complete with weapons, and beginning to create law and order problems on Indian soil. In the North-East itself, the collapse of the Provincial Council appears imminent.

Anon: North-East PC Members killed. Tamil Times, Jan 15, 1990, p. 18.

Two members of the North-East Provincial Council have been murdered. George Thevarajah (sic, Thambirajah), an EPRLF member of the Provincial Council and four others described as his bodyguards were ambushed and killed allegedly by cadres of the LTTE in Trincomalee on 10 January. The victims were killed about six miles away from Trincomalee town on the Nilaveli-Trinco road close to Sampaltivu when they were on their way to attend an EPRLF meeting when LTTE men attacked them. Attended by a large crowd, the funeral of Thambirajah took place on 11 January at Trincomalee, after his body lay in state at the Provincial Council secretariat.

In the second incident, the deputy Speaker of the North-East Provincial Council, Chelliah Ganeshamoorthy and three others described as bodyguards were abducted at Uhana and killed at Chavalakadai in the Amparai distric on 11 January, allegedly by LTTE cadres. Four charred bodies burned beyond recognition and found lying behind the Amparai hospital on 13 January had been identified as those of Ganeshamoorthy and his bodyguards Kingsley Angelo Joseph, Siva and Juli.

Colombo correspondent: Tigers on the prowl again. Economist, Jan 20, 1990, p. 38.

Assuming the Indians do go on schedule, what will happen to members of the EPRLF and other groups that have had the protection of the Indians? The Tigers call them collaborators, with the threat of death that word implies. The Indians have set up a group called the Tamil National Army, which is supposed to take over their duties. But this artificial ‘army’, made up mostly of conscripted teenage boys, is no match for the battle-hardened Tigers. Hundreds of youngsters have been killed as the Tigers swept through the areas evacuated by the Indians.

David Housego: A funeral in Trinco. Lanka Guardian, Feb 1, 1990, pp. 14-15 (a reprint from Financial Times, London).

As the last Indian troops prepare to pull out of Sri Lanka over the coming two months, Tamil Tiger guerrillas are set to take control of the rest of the north and east of the country.

The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), as they are called, already control all six districts from which the Indians have withdrawn. In the seaport of Trincomalee, which is with the Jaffna peninsula the only place where Indian forces remain, the beleaguered Tamil dominated administration is preparing to abandon the town when the Indians depart.

‘We shall go underground’, says Mr. K. Pathmanabha, the general secretary of the EPRLF (the Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front), the main rival to the Tigers which now heads the north-east provincial council. Trincomalee, one of the world’s great natural harbours and a base for Allied fleets in the Second World War, remains much as it was 40 years ago – a result of government neglect of the Tamil north, and more recently of six years of civil war.

Bearded, wearing dark green battle dress with a picture of Lenin pinned to his lapel, Mr. Padmanabha was speaking after the funeral of Mr George Thambirajah, one of his most senior colleagues and the founder of the Tamil National Army (TNA), the alliance of anti-Tiger guerrilla groups that India has equipped. Mr. Thambirajah was killed by the Tigers recently in an ambush that demonstrated their ruthlessness in removing the leaders of other Tamil factions opposed to them.

‘It is an indication of what is to come’ said another EPRLF official, watching the emotional ceremony on the shores of Dutch Bay, Indian officers bearing wreaths stood a few steps in front of an escort from the TNA – many of them boys of 14 or 15 with automatic weapons.

The killing illustrated the inability of the Indians to provide protection for the more moderate Tamil groups though they had earlier made the security of the Tamils who cooperated with the provincial council one of the main points on which their withdrawal would depend.

The Indian peacekeeping force – 80,000 strong at its peak, but now down to 20,000 – arrived more than two years ago for what they believed would be a brief operation to disarm the Tigers. They will finally leave by the end of March with seemingly none of their objectives achieved, more than 1,000 soldiers killed and with their involvement having earned them the hostility of both the Tamils and the Sinhalese population.

Saybhan Samat: The Muslim Factor. Lanka Guardian, Feb 1, 1990, p. 15

As regards, M.H.M. Ashraff, he has used the rising tide of Islamic resurgence of the oppressed and deprived Muslims of Sri Lanka, especially in the Eastern province to serve his own ends.

Since the signing of the Indo-Lanka Accord in July 1987, he claimed that the accord did not meet the aspirations of the Muslims, adding that the Muslims were not consulted. He, however, contested Provincial Council elections which has a necessary pre-condition of the Indo-Lanka Accord. Worse still he conducted his election campaign for the North-East provincial council elections last year in Kalmunai having received all logistical support from the Indian army.

This despite the fact that the Indian army was responsible for killing of Muslims in Jaffna, Vavuniya, Mutur, Kinniya, Ottamawaddi, Valachchenai and Batticaloa, prior to the elections. Recently it was stated in parliament that members of the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress had been inducted to the illegal Indian backed Tamil National Army (TNA).

Anon: Jaffna’s orphans of war. Asiaweek, Feb 9, 1990, p. 27.

The Tiger’s rivals. Grouped under the quadripartite Tamil National Council, are reportedly less sophisticated. Their Tamil National Army (TNA), formed last year, is said to have press-ganged children into its ranks. ‘Boys were taken as they were returning home from school, pulled off buses and trains.’ Recounted a Jaffna resident. ‘In some cases, they came to our homes and just forced the boys to go.’ Among those abducted was a 22 year old named Balasubramaniam who later surrendered to the Tigers. He reported seeing several 13 year olds brought in for training at a TNA camp.

For the child soldiers, the war can be terrifying. The young TNA recruits, correspondent Ranawana saw in Jaffna ‘were frightened and clutching Kalashniko assault rifles barely shorter than themselves. They were desperately trying to defend the city centre against the approaching Tigers.’ The youngsters had reason to be afraid, he said. The previous night, the Tigers had attacked a TNA camp, killing nearly 70 guerillas and thirteen Indian soldiers.

Lisa Beyer: Back roar the Tigers. Time, Feb 12, 1990, pp. 32-33.

While the Tigers are hardly angels – as evidenced by their tax demands – local Tamils overwhelmingly prefer them to the Indian troops and their hangers-on, the Tamil National Army, a slipshod militia raised b the Tigers’ rival, the Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front. While the Indians have allegedly detained thousands of Tamil civilians without cause, TNA fighters have expropriated money and valuables from civilians, often at gunpoint. They have also plundered stores and waylaid trucks bringing provisions into Jaffna, creating shortages of flour, sugar and oil. By contrast, says Narasimhan Balachandran, a cement factory worker, ‘the LTTE is disciplined and polite.’

Wherever the Tigers have moved in, they have easily routed the TNA militiamen, who have put up little resistance. Most members of the TNA’s parent group, the EPRLF, have now fled to India. Says one EPRLF leader: ‘We are safe only there.’

With the Tigers in control, normal life has returned to the northeast. In Jaffna storekeepers who emptied their shelves to discourage TNA looting have restocked them. Trains and night buses to Colombo, suspended for two years, have resumed service.

Rita Sebastian: Taming of the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress? Tamil Times, Feb 15, 1990, pp. 6-7.

On November 5 last year when LTTE cadres stormed two Tamil National Army (TNA) camps in eastern Amparai killing twenty seven TNA personnel and taking another one hundred and forty hostage, together with five truckloads of sophisticated weaponry, the stage was set for what was to follow.

It was only a fortnight earlier that Amparai had seen the last of the Indian troops withdraw and the much publicized take-over of the law and order machinery by the Sri Lankan police and the Citizen Volunteer Force (CVP) turn out to be a mere cosmetic exercise as events proved. The TNA raring to go, soon attacked four Sri Lankan police stations in the district, and 41 Muslim CVF were brutally massacred after being disarmed.

Batticaloa was to ‘explode’ next, as soon as the IPKF withdraw, with an armed confrontation between the LTTE and the TNA. The casualty figure was said to be over eighty dead although both sides played down the numbers as the LTTE drove the remaining TNA cadres into the surrounding jungles.

De-induction from Mannar, Mullaitivu, Kilinochi and Vavuniya followed in quick succession and the Tigers ‘moved in’ but not before the fighting, more bitter and bloody than before, took heavy toll of life. Although the LTTE has been able to take control of the central Wanni sector, and the north, including parts of the Jaffna peninsula from where the IPKF has withdrawn, it is in the Amparai and Batticaloa districts, with its high concentration of Muslims that they have found it hard going to stamp their authority.

All Tamil groups have, in recent times, included the Muslims in their deliberations by using the broad definition of ‘Tamil speaking people’. A number of Muslim youth have been recruited to their ranks to give credence to this, and also ensure Muslim support. Even if a minority of Muslims go along with the idea that language can be the unifying force between the two communities, the majority are fiercely protective of their distinct ethnic identity, and refuse to be assimilated by another minority.

The Sri Lanka Muslim Congress of Mr M.H.M. Ashroff is therefore in no mood to give into Tiger dominance. The LTTE, peeved at the SLMC for having contested the North-East Provincial elections, and also for having a working arrangement with the EPRLF, have come up with a string of allegations against them, the main being of SLMC collaboration with RAW, securing arms from the TNA and setting up its own militia with IPKF assistance.

India still continuing to voice her concerns on the ‘safety and security of the Tamils’ is however not likely to change her mind about troop withdrawal. Crucial to the issue of course is what is going to happen not only to the TNA personnel riding on the backs of the Indian troops, but also to the cadres of other groups fleeing with the withdrawing Indian army.

Thomas Abraham: A failed strategy. Tamil Times, Mar 1990, pp. 17-18. (a reprint from Frontline, Madras, Feb 16, 1990).

In June 1989, after Sri Lankan President Ranasinghe Premadasa’s abrupt demand that the IPKF be withdrawn, India felt that even if the IPKF had to leave, the Provincial Government of Chief Minister A. Varadarajaperumal should not be left at the mercy of the Sri Lankan government and the LTTE. India wanted to see that the provincial government had the means to defend itself after the IPKF left. It decided to continue diplomatic efforts to persuade Colombo to devolve enough powers to make the provincial council a politically and administratively viable unit.

For the security of the Provincial government two forces were set up. One was the Citizen Volunteer Force (CVF), a paramilitary group which would eventually be absorbed in the regular police. This was a legal body, and both the Indian and Sri Lankan governments agreed that the IPKF would train it. The Sri Lankan government was to provide it with weapons and pay. Training centres were set up, and parades were held to recruit volunteers, most of whom were members of the EPRLF and its allies – the Tamil Eelam Liberation Organisation (TELO), and the Eelam National Democratic Liberation Front (ENDLF).

The creation of the CVF was a relatively slow process, though India and the EPRLF were planning the formation of a 10,000 to 15,000-strong force within a matter of months. So it was decided to conscript and train youth forcibly to form what later came to be called variously as the additional CVF or the Tamil National Army (TNA). The EPRLF, the ENDLF and the TELO began two waves of conscriptions in July and September. Teenagers were pulled out of schools and from trains and buses and taken to camps for two months of training by Indian experts. Later the recruits were given weapons by India in areas the IPKF was about to vacate.

In retrospect, the conscription drive was a mistake, politically and militarily. Politically, it alienated the Tamil population from the EPRLF, even in areas such as Batticaloa, considered its stronghold. As one senior EPRLF member admitted later, ‘We have lost 100 percent of our support.’

Militarily, the hurriedly-trained, poorly-motivated army of conscripts has been unable to stand up to the LTTE, as events in Amparai, Batticaloa and Vavuniya have shown. The groups themselves realized that many of the unwilling recruits would run away, but went on with the drive because the number of weapons they were given was linked to the number of recruits they could mobilise. India was handing out weapons to the groups according to the strength of their cadres, and so they were all keen on inflating their numbers by whatever means possible.

The creation of the TNA also annoyed the Sri Lankan government, which did not look kindly on an army being formed on its soil armed and paid for by another government. Colombo was determined to destroy it.

The LTTE attacked two TNA camps in Amparai district shortly after the IPKF withdrew and the TNA retaliated by attacking police stations in the district. The Provincial government justified the TNA action by claiming that the LTTE had been helped by the Sri Lankan army and the para-military Special Task Force (STF) in the attacks. But the attacks on the police stations, in which 13 policemen, four army men and 20 militants were killed, turned the Sri Lankan army and police against the TNA, which meant the TNA had to contend with both the LTTE and the Sri Lankan forces.

Part of the reason for the TNA’s failure was of course the support given to the LTTE by the Sri Lankan government. Both the Tigers and the government staunchly deny any collusion but there is evidence of it. At a very obvious level, the Sri Lankan army has turned a blind eye to the LTTE’s operations against the TNA, under the pretext of not wanting to interfere, while TNA cadres are being arrested by the security forces. There have been allegations that the Sri Lankan government has been providing weapons to the LTTE to fight the TNA and the IPKF. The LTTE leadership denies this, but at least one LTTE guerrilla this correspondent talked to in Vavuniya admitted that the AK47 he was using had been given by the Sri Lankan army.

The EPRLF and its allies have also said Sri Lankan air force helicopters have been used to ferry LTTE fighters across the north and the east, allowing them to concentrate their forces in trouble spots.

Thus the TNA faces a double disadvantage – on the one heand, its own forces are not as motivated or well trained as the LTTE’s; on the other, it has to fight both the LTTE and the Sri Lankan forces.

More serious than the military failures were the political failures, and India’s and the EPRLF’s post-withdrawal strategy failed for essentially political reasons. A glaring error was the EPRLF government’s failure to build popular support in the north and the east, which would have ensured that even if the LTTE was able to take physical control of the town, popular sympathies would have been with the EPRLF. Instead, through measures such as conscription the EPRLF and its allies alienated the people in the north and the east.

Anon: Indian’s exit, Tigers return. Asiaweek, Mar 30, 1990, p. 26.

The exodus has included Tamils who cooperated with the IPKF against the Tigers. Some 1,600 Tamils were granted refuge in eastern Orissa state in early March. They had been rejected earlier by Tamil Nadu chief minister Muthuvel Karunanidhi, who claimed that the asylum seekers included fighters from the Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front. Subsequently, there occurred a mass escape from the Orissa camp March 17; soe of those recaptured possessed arms, seeming to confirm Karunanidhi’s suspicions. Also believed to be among Orissa’s controversial guests was Annamalai Varatharaja Perumal, chief minister of Sri Lanka’s Northeastern province. He had declared it an independent Eelam state before he fled.

Lisa Beyer: No tears here. Time, Apr 2, 1990, pp. 8-9.

The Indian forces made two mistakes that quickly alienated the very people they had come to protect. Because they often found it impossible to distinguish guerrillas from civilians, the troops harassed, beat, arrested and killed innocents in their effort to pin down an elusive army. The Tigers, in turn, used the populace as a shield, resulting in more civilian casualties.

India’s second misstep was the decision to arm a militia, the so-called Tamil National Army (TNA) which, rather than fight the Tigers, extorted from shopkeepers, murdered opponents and forcibly conscripted young men…

Knowing that without the Indians protection they would be liquidated by the Tigers, some 5,000 members of the TNA and its mother group, the Eelam People’s Revolutionary Front, fled to India.

Coda

Despite the expose provided by Rohan Gunaratna in his 1993 book, the notorious deeds of RAW mandarins in Sri Lankan soil during 1980s deserve an in-depth study. This should include (1) the successful assassinations of TULF politicians V. Dharmalingam and M. Alalasundaram in 1985, A. Amirthalingam and V. Yogeswaran, and attempted assassinations of M. Sivasithamparam and LTTE leader V. Prabhakaran in 1989 through RAW’s conduits in TELO and LTTE. (2) deeds of RAW officials in deliberately splitting the Tamil and Muslim populations of the Eastern region, between 1987 and March 1990, via their active sponsorship of EPRLF and TNA cadres, as well as promoting Ashroff’s Sri Lanka Muslim Congress in its incipient days. (3) RAW’s deals with the jingoistic JVP and its splinter groups like ‘Vikalpa Kandayama’ clique (Dayan Jayatilleke and Dayapala Thiranagama): facilitating their contacts to escape to India and elsewhere via devious routes.

Among the Sinhalese, the dumb Sinhalese journalists and opinion makers who couldn’t differentiate between a ‘bald head and a knee cap’ (this is a popular Tamil idiom of ‘moddai thalai and muLankaal’ – both have surface similarity, but they are different), promoted disinformation that LTTE was the chief beneficiary of RAW’s support and training; whereas the truth was TELO, EPRLF and ENDLF militant groups were the handpicked pawns of RAW mandarins for distorting the cherished LTTE ideal of separate state for Tamils. It was inevitable that these three disoriented Tamil militant groups had leadership deficit and lost out to LTTE for want of discipline and lack of focus in their original aim while pretending to carry ‘Eelam’ in their names; and the human rights barkers in the caliber of Rajan Hoole et al. paid homily for the dead with a Biblical allusion ‘Trincomalee & The Sword of Cain’ [University Teachers for Human Rights (J), Report 12, chapter 6].

In the above mentioned report, little personal detail is presented about George Thambirajah, the doomed leader of TNA, and his fate on January 9, 1990. To quote, ‘ George was travelling to Nilaweli in his jeep with the customary IPKF escort behind. The LTTE, firing from a distance, stalled George’s vehicle. George was killed while trying to get away on foot. The IPKF reportedly did not intervene to save him.’ How old was George Thambirajah at the time of his death? No details are given. Then, Hoole et al. had provided three verdicts from the local folks – a positive, a negative and a neutral, with an understatement, “For those who lost near ones for which George is held responsible, there is no forgiving him.” Nevertheless, for want of better perspective, I give below what Hoole et al. had gathered on Thambirajah’s adventurous ride with IPKF and RAW.

Positive: ‘George was a dedicated leader in many ways. When he came back to Trincomalee with the IPKF, he placed the well-being of the cadre under him first. He drank plain tea and ate poorly. In the nights he often kept watch while others slept. If he wanted position, such as that of a minister, he could have taken it. But he did not crave for power.’

Neutral: ‘These boys had several good qualities and the IPKF could have used them positively. Instead the IPKF used them as killers and destroyed them.’

Negative: ‘He was a good boy. But with the onset of his role in the provincial administration, he changed for the worse.’

As is their practice of masking identity, Hoole et al. hardly identified the individuals (by name, sex, and or age).

Sources

Adele Balasingham: The Will to Freedom – An Inside view of Tamil Resistance,

Fairmax Publishing, Mitcham, UK, 2001, 380 pp.

Rohan Gunaratna; Indian Intervention in Sri Lanka – the role of India’s Intelligence Agencies, South Asian Network on Conflict Research, Colombo, 1993, 500 pp.

M.R. Narayan Swamy: Tigers of Lanka – From Boys to Guerrillas, 2nd ed., Vijitha Yapa Bookshop, Colombo (original publisher Konark Publishers, Delhi), 1996, 358 pp.