by T. Sabaratnam, March 15, 2004

Volume 1, Chapter 32

Original index of series

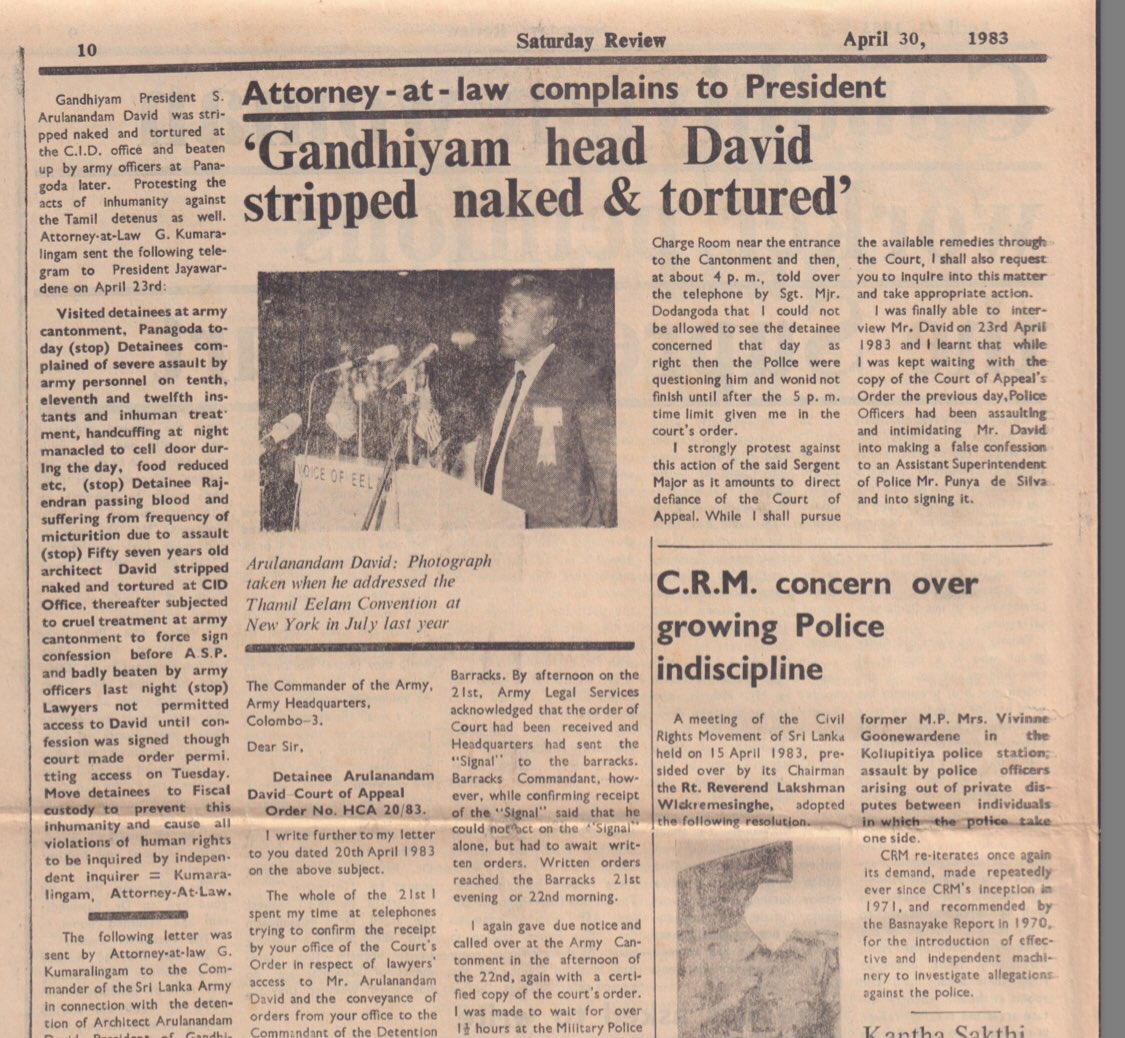

Dr S Rajasundaram

Grabbing Land

A joint police and army team led by police detectives raided the Pankulam settlement of Tamils of the Indian origin on the orders of Vavuniya Assistant Government Agent at 10 a.m. on 6 April 1983 and set fire to their crops and huts. They then raided the Gandhyam head office in Vavuniya and took its organizing secretary, Dr S Rajasundaram, to Gurunagar army camp for questioning. Two days later, they arrested Arulanandam David, Gandhyam’s founder president. Both were taken into custody under the notorious Prevention of Terrorism Act.

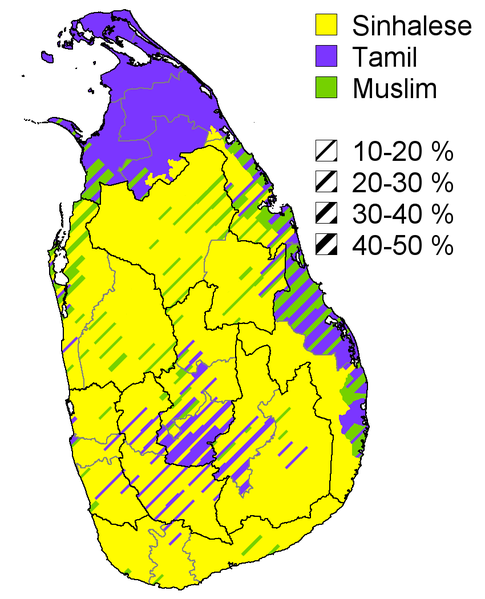

The well-organized sweep on Gandhyam, a charitable organization engaged in rehabilitating Indian Tamil families chased out of the hill country by Sinhalese mobs during the 1977 riots, was part of a carefully planned program of Jayewardene’s government to knock out the territorial base for the Tamil claim of Tamil Eelam, a contiguous homeland. Tamils claim that the northern and eastern provinces constitute their traditional homeland and they have the right to govern that region. The Sinhalese dispute that claim and Jayawardene set out to destroy the very base of that claim.

State-aided Sinhala colonization of the eastern and northern provinces was the original provocation for Tamils to claim autonomy for the northeast under a united, federal Sri Lanka. Originally, state aided colonization was thought of as one of the solutions to Sri Lanka’s problem of rural landlessness. It was first advocated by the British Governor, Sir Hugh Clifford, in 1927, but he cautioned that land was a very sensitive matter to all communities in Sri Lanka and they get emotional about it. His suggestion was to settle the landless persons of the wet zone in the unexploited areas in the dry zone.

Sir Hugh’s proposal was referred to a Land Commission appointed by the Legislative Council in 1927. The Commission identified vast stretches of undeveloped land in Kurunegala, Anuradhapura, Trincomalee, Mannar, Mullaitivu and Jaffna for settlement. In 1933 Agriculture Minister D. S. Senanayake presented the Land Development Ordinance which provided for the systematic development of crown lands. It provided for the allocation of state land for village expansion, government use and establishment of agricultural settlement.

The earliest land alienation for peasants was established in Minneriya where Sinhalese farmer-families were settled. That was followed by a scheme to settle Tamil farmer families in Kilinochchi in the Northern Province. Then, Sinhalese were settled in Polonnaruwa and Anuradhapura. Everything looked fair and fine. Tamil landless peasants were settled in Tamil majority areas and Sinhala landless peasants were settled in Sinhala majority areas. Tamils, like the Sinhalese, welcomed state-aided colonization.

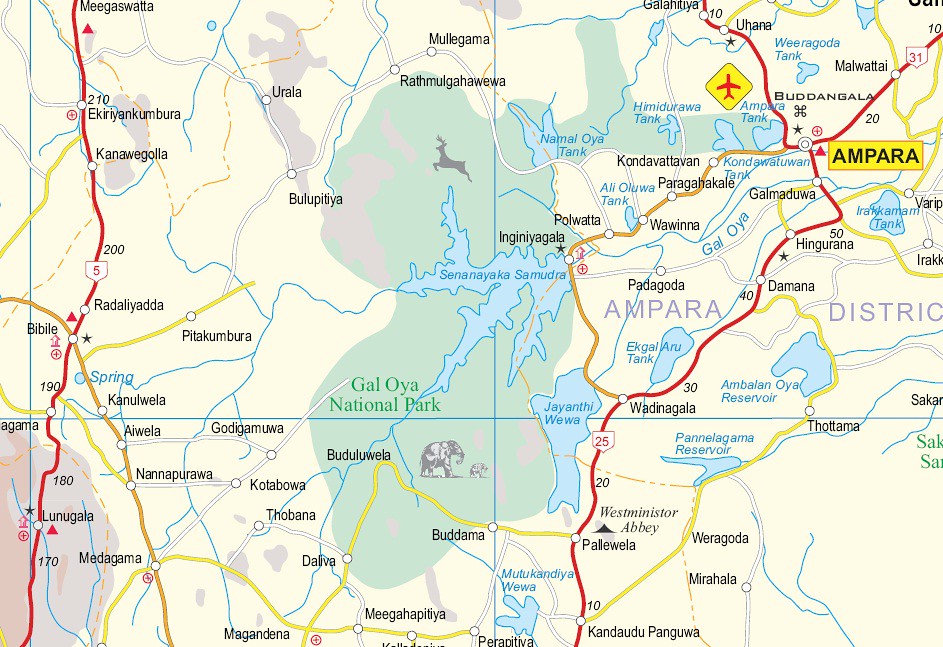

Everything changed in 1949, a year after Sri Lanka attained independence from British rule, with the inauguration of the Gal Oya Scheme. In February that year, Sri Lanka’s first prime minister, D. S. Senanayake, summoned his permanent secretary Sir Kandiah Vaithiyanathan, Director of Irrigation T. Alagaratnam, and Surveyor General Dr. S. Brohier, and told them of his intention to construct a massive irrigation scheme by building a dam across the Paddipalai Aru. He told them that that irrigation scheme would benefit the farmers in the Tamil villages in the region and Sinhalese farmer families could be settled in the excess irrigable land. He instructed Alagaratnam to do the feasibility study.

Alagaratnam told Virakesari in an interview how enthused he and Sir Kandiah Vaithiyanathan were when the prime minister announced his plan. “We never dreamt that he had at the back of his mind a scheme to grab the Tamil land.”

Alagaratnam and his group of irrigation department officials traveled to the Muslim village of

reach the Bay of Bengal. The study group first went to Paddipalai, a prosperous Tamil village with a rich history extending to over 3rd Century BC. From there it went to Inginiyagala, where it discovered a convenient spot suitable to build a dam. The Alagaratnam Committee recommended the construction of an irrigation scheme.

Samanthurai and traveled upstream in block carts. Paddipalai Aru originates from the Madulseema mountain range in the Badulla district and runs down about 85 kilometers to

The prime minister, on the basis of the recommendation of the Alagaratnam Committee report, enacted in parliament legislation to set up a special board to handle the construction and settlement work. He named it the Gal Oya Development Board. The Tamil name Paddipalai Aru was given a Sinhala name Gal Oya. Thus began the process of changing Tamil names into Sinhala, an effort to which Sinhala ‘scholars’ lent their blessing and ‘research.’

Prime Minister D. S. Senanayake inaugurated the construction of the Gal Oya project at Inginiyagala on 28 August 1949 and consturction was completed by the end of the next year. The reservoir was named Senanayake Samudra.

The development scheme, which encompassed 120,000 acres, was divided into 40 settlements and in each settlement 150 farmer families were allocated five acres each. Only six of those settlements were allocated to the Tamils and the Tamil settlers, numbering 900 families, were mostly local residents. Over 7,000 Sinhalese families were settled in the settlements allocated to the Sinhalese. All of the Sinhalese were brought from outside. Thus, D. S. Senanayake, whom the Sinhalese call the father of the nation, became the father of the land grab movement and the father of Sri Lanka’s ethnic dispute.

Prior to the commencement of the Gal Oya scheme the Eastern Province comprised of Trincomalee and Batticoloa districts.

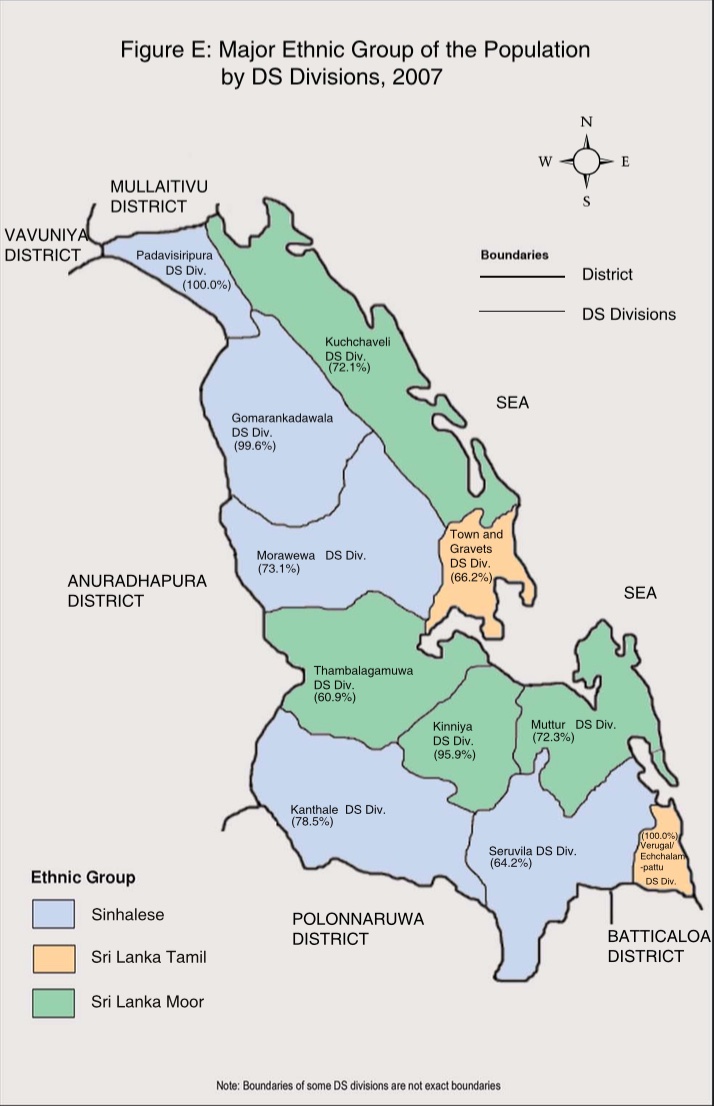

Ampara district was created in 1961 by bifurcating from the Batticoloa district the areas colonized with Sinhalese.

In the 1911 census, the area carved out to create the Ampara district was a Muslim majority area with Tamils coming second and Sinhalese third. The Muslim population in 1911 was 36,843 (55%), Tamils 24,733 (37%) and Sinhalese 4,762 (07%). In the 1921 census the population in that area was: Muslims 31,943, Tamils 25,203 and Sinhalese 7,285. The result of the Gal Oya scheme and the associated Sinhala colonization is reflected in the following census figures:

In 1953: Muslims 37,901, Tamils 39,985 and Sinhalese 26,459.

In 1963, Muslims 97,990 (45.6%), Sinhalese 62,160 (29%), and Tamils 49,220 (23.5%). Tamils had been pushed to third place by the Sinhalese.

In 1971 Muslims 123,365 (47%), Sinhalese 82,280 (30%) and Tamils 60,519 (22%).

In 1981 Muslims 166,889 (47%), Sinhalese 146,371 (38.01%) and Tamils 78,315 (20%). Since then Sinhalese have moved to first place.

Tamils who were settled in six settlements were chased away during the first riots against the Tamils in June 1956. Those who returned to their lands after the riots were again chased away during the second riots in May 1958. The few who returned after that were chased away by the army in 1990. Since then Sinhalese colonists are cultivating the lands allocated to the Tamils and the Gal Oya scheme is ethnically cleansed.

Courtesy TamilNet May 2017

Trapping Trincomalee

D. S. Senanayake was not content with settling Sinhalese in the Batticoloa district. He also inaugurated the move to grab land in the Trincomalee district. Vanni in the north and most parts of the eastern province were prosperous agricultural areas with well developed tank-irrigated rice cultivation networks. Similar networks were prevalent in the dry zones in the Sinhala majority south and in Tamil Nadu in South India. Tank irrigation was the conventional agricultural practice of the region and is common among both the Tamils and the Sinhalese. Trincomalee district is dotted with such irrigation networks. Kanthalai Kulam – kulam is a small-sized tank – was one of them. It provided irrigation to the rice fields in the Tamil villages of Thambalagamam and Kinniya. D. S. Senanayake renovated and deepened the tank under the Kanthalai Development Scheme in 1948 and settled Sinhala colonists by bringing fresh areas under cultivation.

The Kanthalai Scheme commenced the process of settling a substantial number of Sinhalese in the Trincomalee district. Of the 86,000 Sinhalese who lived in the Trincomalee district in 1981 40,000 resided in Kanthalai Development Scheme region.

Encouraged by the success of the Kanthali colonization, D. S. Senanayake started the Allai Scheme in 1950. It was completed by his son, Dudley Senanayake, who succeeded him when he died in 1952.

The Allai Scheme was started by Don Stephen Senanayake building a dam across Verugal Aru, a tributary of the Mahawali Ganga to the south of Trincomalee Bay. This area was formerly known as Koddiyar. Tamils and Sinhalese lived there, but the Tamils were in the majority.

By the beginning of the 20th Century there was only one divisional secretariat division in that area known as Koddiyar Divisional Secretariat. Now there are three: Mutur, Seruvila and Verugal. Seruvila division was created in 1960 and Verugal division in 1980 to cater the needs of the Sinhala colonists settled there. In 1981, out of the 20,187 persons who lived in the Seruvila division, 11,665 were Sinhalese who had been brought from outside.

The Sinhala governments did not stop with colonizing unsettled Tamil areas with Sinhala farmers. They foisted Sinhala colonists on traditional Tamil villages and renamed them to show that they were Sinhala villages. The villages of Pulasthigama and Kankayapaduna serve as examples. They also changed the names of ancient Tamil villages into Sinhala.

The Tamil village Arippu was given the name Serunuwara, Kallaru the name Somapura, Neelapallai the name Nilapola, Poonagar the name Mahindapura and Thirumangavai the name Dehiwatte.

By 1951, state-aided colonization of the Eastern Province emerged as a major point of dispute between the Sinhalese and the Tamils. Prime Minister D. S. Senanayake in his Independence Day address on 4 February 1951 claimed the accelerated agricultural settlements as a major achievement of his government.

This claim irritated the Tamils.

State-aided Sinhala colonization of the traditional lands of the Tamil-speaking people was continued with added vigour by the subsequent governments. The S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike government commenced the Padaviya colonization scheme to the east of Vavuniya in 1956. It was started with the intention of settling the workers who lost their jobs when Trincomalee harbour, which was under the British, was taken over by Sri Lanka. The government wanted to settle 595 Tamil families and 453 Sinhala families. The Sinhalese, with the help of Buddhist priests, objected to the settlement of the Tamils, and Sinhala families forcibly occupied the huts built to settle Tamil families. Thus Padaviya was turned into a Sinhala colonization scheme.

The Sirimavo Bandaranaike government started the Morawewa Scheme in 1960. The original name of Morawewa tank was Mudali Kulam, an ancient Tamil settlement. In 1981 the population of Morawewa was 9271 of which 5101 were Sinhalese, all of whom had been brought from outside the region. The Mahadivukwewa Scheme was started by the Jayewardene government. The ancient Tamil name Periyavilankulam was translated to the Sinhalese Mahadivulwewa.

Apart from the state-aided colonization schemes, politically-backed illegal Sinhala colonization schemes also sprang in the Trincomalee district. The motivation behind such schemes was to convert Trincomalee district into a Sinhala majority district. In 1972 the ancient Tamil settlement Nochikulam was christened Nochiyagama and Sinhalese were settled on 5000 acres. In 1973 the government-backed Sinhala chauvinistic organizations commenced a new type of Sinhala settlement.

They settled Sinhala families in the state land surrounding Tamil villages. Such illegal settlements were set up around the Tamil villages Kuchchaveli, Pulmoddai, Thihiriyai and Thennamaravadi. About 10,750 Sinhala families were settled through this scheme. Table 3 in the Introduction to this series illustrates the extent of the changes Sinhala colonization has effected to the racial composition of Trincomalee district.

State-aided and illegal colonization schemes also had another sinister objective. They were intended to sever the links the Tamils living in Trincomalee had with the Tamils living in the north and the Batticoloa – Amparai region. The Sinhala settlements were located on both sides of the four main roads that connect Tamil-majority Trincomalee town with the rest of the country. The Kanthalai Scheme is on the Trincomalee – Kandy road. The Allai Scheme is on the Trincomalee -Batticoloa road. The Morawewa Scheme is on Trincomalee – Vavuniya road. The Padaviya Scheme is on the Trincomalee – Mullaitivu road. In case of an attack on the Tamils in Trincomalee town, they have no escape route. This is the reply the Sinhala government has given to the Tamil intention to make Trincomalee the capital of Tamil Eelam.

State-aided and illegal colonization schemes also had another sinister objective. They were intended to sever the links the Tamils living in Trincomalee had with the Tamils living in the north and the Batticoloa – Amparai region. The Sinhala settlements were located on both sides of the four main roads that connect Tamil-majority Trincomalee town with the rest of the country. The Kanthalai Scheme is on the Trincomalee – Kandy road. The Allai Scheme is on the Trincomalee -Batticoloa road. The Morawewa Scheme is on Trincomalee – Vavuniya road. The Padaviya Scheme is on the Trincomalee – Mullaitivu road. In case of an attack on the Tamils in Trincomalee town, they have no escape route. This is the reply the Sinhala government has given to the Tamil intention to make Trincomalee the capital of Tamil Eelam.

Sinhala governments have also turned Trincomalee and environs where Sinhala settlements have been started into a security fortress. A Naval Camp is located at Trincomalee harbour. Airforce camps are established at China Bay and Morawewa. About half of the 300 army camps set up in the Northeastern province are sited at and or around Trincomalee.

Vavuniya district also was affected by Sinhala colonization. Adjustments in the borders of the Vavuniya and Trincomalee districts were resorted to bring in the Padaviya scheme into Vavuniya district to enable the creation of a new Divisional Secretary Division – the Vavuniya South division – to extend the areas under Sinhala colonization into the Vavuniya district.

Illegal Sinhala settlements were also encouraged. In 1881, the population of Vavuniya district comprised 13,164 Tamils and 1157 Sinhalese. In 1981, it was 54,179 Tamils and 15,794 Sinhalese.

Effect of Sinhala Colonization

State-aided Sinhala colonization in the northern and eastern provinces impacted on the Tamils in three ways. Firstly, it altered the demographic pattern of the traditional areas of habitation of the Tamils, especially in the eastern province. Secondly, it deprived the Tamils of a considerable extent of rich agricultural land. Thirdly, it reduced Tamil representation in parliament.

The change effected on the racial distribution in the Eastern Province through planned state-aided Sinhala colonization is well illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1

Demographic change in the Eastern Province (1881- 1981)

| Year | Sinhalese | Tamils | Muslims |

| 1827 | 250 1.3% |

34758 75.65% |

11533 23.56% |

| 1881 | 5947 4.5% |

75408 62.35% |

43001 30.65% |

| 1891 | 7512 4.75% |

87761 61.55% |

51206 30.75% |

| 1901 | 8778 4.7% |

96296 57.5% |

62448 33.155% |

| 1911 | 6909 3.75% |

101181 56.2% |

70409 36% |

| 1921 | 8744 4.5% |

103551 53.5% |

75992 39.4% |

| 1946 | 23456 8.4% |

146059 52.3% |

109024 39% |

| 1953 | 46470 13.1% |

167898 47.3% |

135322 38% |

| 1963 | 109690 20.1% |

246120 45.1% |

185750 34% |

| 1971 | 148572 20.7% |

315560 43.9% |

248567 34.6% |

| 1981 | 243358 24.9% |

409451 41.9% |

315201 32.2% |

Table 2 illustrates the impact on the North-East, the traditional homeland of the Tamils.

Table 2

Change in the racial composition in the North-East (1881-1981)

| 1881 | 1946 | 1981 | |||||||

| Sinhala | Tamil | Muslim | Sinhala | Tamil | Muslim | Sinhala | Tamil | Muslim | |

| Jaffna District | 0.3 | 98.3 | 1.0 | 1.07 | 96.3 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 97.7 | 1.7 |

| Mannar District | 0.67 | 61.6 | 31.1 | 3.76 | 51.0 | 33.0 | 8.1 | 63.7 | 26.6 |

| Vavuniya District | 7.4 | 80.9 | 7.3 | 16.6 | 69.3 | 9.3 | 16.6 | 76.3 | 6.9 |

| Batticaloa District | 0.4 | 57.5 | 30.7 | 4.0 | 69.0 | 27.0 | 3.4 | 72.0 | 23.9 |

| Amparai District | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 38.1 | 20.0 | 47.0 |

| Trincomalee District | 4.2 | 63.6 | 25.9 | 20.7 | 40.1 | 30.6 | 33.6 | 36.4 | 29.0 |

Sinhala representation also rose with the introduction of the proportional representation system of election. In the

parliamentary election of 1977 two Sinhalese were elected from the eastern province, one each from Ampara and

Seruvila. Since the introduction of the proportional representation system in 1978 Sinhala representation from the

eastern province has risen to five and a Sinhala representative was elected from the north.

Tamil Reaction

Tamil resistance to Sinhala domination commenced in March 1950, six months after D. S. Senanayake inaugurated

the construction work on the Gal Oya project and three months after the formation of the Federal Party on 18 December 1949. The Federal Party timed its stir to coincide with the settlement of the Sinhala colonists in the first settlement. It also opposed the renaming of the river Padipalai Aru to Gal Oya.

The Federal Party agitation sowed in the Tamil mind the feeling that the Sinhala governments are out to grab their land and laid the foundation for Tamil unity. The Gal Oya colonization bred a sense of solidarity, for the first time, among the Tamils of the north-east, especially among the Tamils living in the southern part of the Batticoloa district.

Tamil reaction to Sinhala land grab took two forms: preventing the state from continuing its Sinhala colonization program through democratic agitation and incorporating specific provisions in the political agreements signed with Sinhala leaders, and through the settlement of Tamil peasants in the border areas.

Sinhala colonization of the Eastern Province surfaced as the main concern of the Inaugural National Convention of the Federal Party held in Trincomalee in April 1951. The Federal Party leader S. J. V. Chelvanayakam warned the Tamil people of the dangers that lay ahead of them in his presidential address.

He warned:

“Population and land are the main safeguards for a minority community. The Sinhala government has begun to attack both. By depriving the Indian Tamils of their citizenship they reduced the population of the Tamil community. By commencing Sinhala settlements in Gal Oya and Kanthalai they have started to attack the land of the Tamils… Today it is Gal Oya and Kanthalai, tomorrow it will be Padaviya, Vavuniya and Mannar.”

The Convention adopted a special resolution condemning state-aided colonization in Tamil majority areas with the aim of making them minorities in their traditional areas of habitation.

The resolution said:

Tamil-speaking persons have inalienable and fundamental right to the lands in which they had lived for generations. By starting planned, exclusive Sinhala settlements the government is violating the fundamental

rights of the Tamil speaking people. The Inaugural Convention of the Federal Party condemns this effort as an

attempt to destroy the settled life of the Tamil speaking people.

The attack on the Tamil population Chelvanayakam referred in his presidential address was to the enactment of citizenship laws by the D. S. Senanayake government which deprived nearly a million persons of Indian origin their citizenship rights.

That reduced Tamil representation in parliament and their share of state power.

After the 1950 March Gal Oya agitation Thanthai Chelva made safeguarding of Tamil territory his major concern and sloganized: suvar irunthalthan cithram varaiyalam, which means the wall must be retained if you want to paint on it.

Protecting the ‘wall’ became one of the main resolutions in all subsequent annual conventions of the Federal Party and Thanthai Chelva’s main preoccupation in the negotiations he had with Sinhala leaders and the agreements he entered with them. Prevention of state-aided Sinhala colonization of Tamil homeland was the cornerstone of the two agreements he entered into with two Prime Ministers.

In the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayakam Pact (B- C Pact) he signed with Prime Minister S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike on 25 July 1957, Chelvanayagam ensured that the administration of the colonization schemes was brought under the regional councils to be set up under the agreement. The relevant section in Part B of the Pact reads:

6. It was agreed that in the matter of colonization schemes the powers of the regional councils shall include the power to select allottees to whom land within their area of authority shall be alienated and also power to select personnel to be employed for work on such schemes. The position regarding the area at present administered by Gal Oya Board in this matter requires consideration.

In the Dudley Senanayake-Chelvanayakam Agreement he signed with Prime Minister Dudley Senanayake on 24 March 1965 he incorporated further safeguards so that the Tamil territory would be retained by the Tamil people. The final part of the agreement deals with this. It reads:

4) The Land Development Ordinance will be amended to provide that citizens of Ceylon be entitled to the allotment of land under the Ordinance.

Mr. Senanayake further agreed that in the granting of land under colonization schemes the following priorities be observed in the Northern and Eastern provinces.

(a) Land in the Northern and Eastern provinces should in the first instance be granted to landless persons in the district.

(b) Secondly, to Tamil-speaking persons resident in the northern and eastern provinces.

(c) Thirdly, to other citizens in Ceylon, preference being given to Tamil citizens in the rest of the island.

The failure of both pacts knocked away the safeguards Thanthai Chelva tried to build into the solution he reached with the two Prime Ministers. That left the Sinhala leadership able to carve out chunks of Tamil territory and to alter the demography of the Tamil majority NorthEast.

As of 2012

Tamils also took steps to safeguard their homeland by settling down in the border areas. J. D. Arudpragasam’s (Arular’s) father, J. Arulappu, was one of the pioneers. Arulappu, a teacher and a Federal Party activist, bought land owned by the Catholic Church in Kannadi near the Madhu Church and set up his own farm in 1964. That encouraged some committed Tamils to migrate to the agriculturally rich Vanni.

Two years later an organized attempt was made by the Federal Party Youth League to create a Tamil settlement in a place called Kithul Oorttu in the Trincomalee district. Enraged by the news that Sinhala farmers were to be settled around a renovated tank in the Trincomalee district Tamil youths forcibly occupied the settlement. The Trincomalee Government Agent, a Sinhalese, ordered them to evacuate the area. When they refused he with the help of the police and his officials set fire to the huts and got them arrested. The Federal Party, which was in the Dudley Senanayake government, persuaded the prime minister to work out a settlement whereby some of the allotments were given to the Tamils.

Arulappu’s pioneering effort and the Kithul Oorttu settlement were exceptions. The preference of Jaffna Tamils of that time was government service. The movement to settle down in the jungle border areas failed to win support among Jaffna Tamils. The efforts of militant Tamil youths to start settlements in Vanni in 1977 also failed to evince support.

Another section of Tamils, however, people of Indian origin who worked in tea and rubber estates, were willing to settle down in the northeast and adopt agriculture as their livelihood. Their lives had been disrupted following the nationalization of British-owned estates in the 1970s. They were unemployed and were forcibly evicted from the estates where they had lived for generations. They drifted towards the northeast, especially to Vavuniya and Batticaloa.

Politically-backed Tamil groups settled them in those districts. A few settlements sprung up in 1975 in the Kalkudah electorate represented by K. W. Devanayagam. The government reacted with anger. It ordered the police to evict the settlers. Their huts were torched. Some were beaten, arrested and remanded. Devanayagam and Thondaman sent telegrams to Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi requesting her to take up the matter with Sirimavo Bandaranaike.

Batticoloa District Judge Shanmuganathan, to whom the evicted settlers petitioned, ruled the police action unlawful. That enabled them to return to their settlements in Punanai and other interior areas. Their success in life prompted a steady flow of hill country Tamils to the border areas of the northeast. This flow swelled following the 1977 riots, when premeditated violence was unleashed on Tamils living in predominantly Sinhala areas.

The plight of Tamil refugees, most of them very poor, motivated many Tamils. A group of such motivated men met at Saraswathy Hall, the main refugee camp in Colombo, and formed an organization to settle the refugees in the border areas of the northeast. The organization was named the Tamil Refugees Rehabilitation Organization (TRRO). K. C. Nithiyanantha, a veteran trade unionist, was elected the president and K. Kandasamy, then a successful corporate lawyer, the secretary.

TRRO organized some settlements in border areas in Trincomalee, Mullaitivu and Vavuniya, but concentrated more in providing resources to other organizations.

Gandhyam

Gandhyam was one such organization. It was founded by two idealists, Dr. S. Rajasundaram and S. Arulanandan David, an architect. Both had been involved in refugee resettlement work since the beginning of the 1970s, but founded Gandhyam after the 1977 riots. It provided the refugee-settlers agricultural advice, facilities and materials. Volunteer workers ran schools and day care centres for children. The U.S. agency C.A.R.E. supplied packets of Triposha — balanced cereal food for children. N.O.V.I.B. and O.X.F.A.M. helped Gandhiyam. Within two years these settlers became self-supportive and self-sufficient.

Dr. Rajasundaram was in London with his wife, Dr. Shanthy Karalasingham, who graduated in 1967 from Peradeniya Medical Faculty when the 1977 riots broke out. Both were distressed and disturbed. They decided to return to Vanni and continue Dr. Rajasundaram’s earlier pioneering mission of providing a new life to the displaced. Dr. Shanthy opened a medical clinic in Vavuniya town and Dr. Rajasundaram took up his rehabilitation work. He operated from the Gandhyam head office in Vavuniya.

Dr. Rajasundaram’s humanitarian work earned the ire of the Sinhala officials and police in Vavuniya. They launched a campaign against him and the Gandhyam Movement. News items and articles attacking the Gandhyam Movement was planted in the Sinhala and English press. Those reports portrayed Gandhyam as a TULF movement to grab state land.

Vavuniya police that planted these news stories and articles were then unaware that Dr. Rajasundaram was a virulent critic of the TULF in general and Amirthalingam in particular. Police was also not aware that the LTTE, then under the leadership of Uma Maheswaran, had started its own farm named Poonthoddam and Dr. Rajasundaram was associating closely with Uma Maheswaran.

By December 1978 the first sowing of black gram (ulunthu) had yielded a bumper crop and Dr. Rajasundaram’s settlement scheme had proved a success. One day during that time Dr. Rajasundaram took a foreign visitor around the farm who was thrilled with the experiment. Dr. Rajasundaram took his visitor to a hut of a settler and, while enjoying the refreshments served by the peasant, he opened up his heart.

“A lot of opposition is building up in the South about this project. Police and Sinhala officials are against it. There are rumours that Sinhala mobs from Madawachchiya might be instigated to attack these settlements and chase away the settlers,” he confided. Then added: “I see one way out. That is to train some youths in firearms so that they can defend themselves.” He had arranged for such training after PLOTE was formed.

Anti-Gandhyam propaganda heightened after Herath was appointed Assistant Superintendent of Police in Vavuniya. He sent a series of reports to the defence ministry through the Inspector General of Police urging action to evict the “unauthorized Indian settlers.” The reports were considered at the top security council meetings at which Jayewardene presided. Jayewardene directed Trade, Commerce and Shipping Minister Lalith Athulathmudali to investigate the matter and report to him. Lalith went on an inspection tour in early December 1982.

He wanted the inspection to appear like a normal ministerial tour and organized the opening of a Sunday pola (market) in Mankulam. I was among the group of media personnel taken by the ministry to cover the event. We were put up at the Mankulam rest house on Saturday night where a get together was organized. ASP Herath attended it. He briefed the media about the problem of the agricultural settlements. He stressed that stateless Indians who were not entitled to get state land were being settled by the TULF through front organizations like TRRO and Gandhyam.

After the general briefing he took me to one side and tried to work up my Jaffna sentiments, knowing my Jaffna origin.

“These are the lands that should go to Jaffna farmers. But they are settling Indians,” he said. Next day I learnt from local Jaffna traders that he had been instigating the Jaffna Tamils living there against the Indian Tamils.

We were taken on a tour to see the agricultural settlements after the opening of the market. We saw prosperous-looking Indian Tamil settlers irrigating their crop. Lalith had secret meetings with the police and the army. We later learnt that a plan to evict the Indian farmers was hatched at those meetings. The plan was not implemented in a hurry. The necessary atmosphere was created by planting news stories and articles in the press. Accusations were made that Gandhyam was recruiting Indian Tamil cadres to PLOTE.

The Vavuniya headquarters of Gandhyam was raided on 6 April and Dr. Rajasundaram was taken away. His organization’s offices in Vavuniya, Trincomalee and Batticoloa were sealed. David, a bachelor, was arrested while in his room in the Colombo YMCA. After investigations at Gurunagar Dr. Rajasundaram and David were detained in the Panagoda Army Camp. They were tortured at the camp and forced to sign a confession. Lawyer Kumaralingam took up their case. He sent a petition to the president stating that David was passing blood and was suffering from frequency of micturation. He also moved the court and obtained an order which allowed him access to David. The court directed Colombo Judicial Medical Officer Dr. S. L. Salgado to examine David and Dr. Rajasundaram. He said in his report that Dr. Rajasundaram had been badly assaulted and tortured.

The police through Minister Cyril Mathew and the media launched a campaign to discredit the detainees. Mathew tabled pornographic literature in parliament claiming that they were recovered by the police from David’s room at the YMCA. He did not state how he obtained them from the police. The Criminal Investigation Department (CID) through the usual media leaks said Dr. Rajasundaram had tried to make peace between the warring LTTE and PLOTE and has asked French authorities to provide weapons training to some Tamil youths. The Attorney General’s Department decided that those materials were insufficient to charge them before courts. While these legal quibbles proceeded the country slid towards the 1983 pogrom that changed Sri Lanka’s history forever.

Next: Chapter 34: Tamils Accept Militant leadership

To be published on March 24.