FAMILIES OF MISSING TAMIL PEOPLE IN THE JAFFNA, SRI LANKA STAGED A PROTEST IN DECEMBER 2015 TO EXPRESS THEIR DISAPPOINTMENT WITH A PRESIDENTIAL COMMISSION ON DISAPPEARANCES IN THE COUNTRY. IMAGE COURTESY OF TAMIL GUARDIAN.

by Gowri Koneswaran, ‘The Alignist,’ December 22, 2015

The first of Tamil poet and professor R. Cheran’s escapes was in July 1979, the day the Sri Lankan government enacted the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) and immediately began arresting members of the country’s second largest ethnic group — including him and his roommates. A university student in the historic Tamil city of Jaffna at the time, he addressed the experience and some of its impacts in his poem, “Two Mornings and a Late Night.”

Enforcement of the PTA, which allows for arbitrary detention, unfair trials, and torture, now finds many Tamil political prisoners languishing in jail, having been detained for decades without charge. Despite the conclusion of the country’s long and brutal armed conflict six years ago and the government’s explicit commitments to the U.N. Human Rights Council in September to review and repeal the PTA, the draconian law is still in effect. Many detainees’ identities remain a secret, which is of particular concern considering evidence that successive governments engaged in “massive” and “systemic” enforced disappearances, including the use of underground detention camps.

The issue of disappearances in Sri Lanka is getting renewed attention through Amnesty International’s “Silenced Shadows” poetry contest, in which Cheran is a judge. A professor in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at the University of Windsor, Canada, he has published fifteen books of poetry in Tamil. In A Time of Burning, a collection of his works which were translated into English by Lakshmi Holstrom, received the English PEN award in 2013.

The issue of disappearances in Sri Lanka is getting renewed attention through Amnesty International’s “Silenced Shadows” poetry contest, in which Cheran is a judge. A professor in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at the University of Windsor, Canada, he has published fifteen books of poetry in Tamil. In A Time of Burning, a collection of his works which were translated into English by Lakshmi Holstrom, received the English PEN award in 2013.

Writer and lawyer Gowri Koneswaran spoke with Cheran for THE ALIGNIST about his poetry, the current human rights situation in Sri Lanka, and Amnesty International’s contest. The conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity, is below.

1. Given the current situation in Sri Lanka, what role does something like the “Silenced Shadows” poetry contest play for communities in Sri Lanka and in the diaspora?

We must begin by asking, “What is the importance of poetic imagination for humanity — and how is it different from political imagination, constitutional imagination, and sociological imagination?” In my view and in my understanding, I’m always convinced that the poetic imagination is far superior [to] any other kind of imagination in terms of addressing issues of resistance, oppression, dominance, equality. […] That’s why poetry should be available in most kinds of struggles.

Second, we should not deceive ourselves by believing that poetry is a panacea for all the evils in the world. There are certain kinds of limitations to what poetry can achieve. One crucial thing is that, in order to create awareness, poetry can be one useful and powerful tool. It works at the individual level too. Little by little, you cultivate and try to influence the reader. It’s a slow but extremely important process. There’s a Tamil saying — “Even if an ant continues to work on the hardest stone possible, little by little the stone will begin to crack.” […] That’s the kind of perspective I have about the role of poetry in these kinds of scenarios.

In the case of Sri Lanka, literary organizations in Sri Lanka and South Asia have been inactive. There’s been an unwritten rule to not discuss or talk about these [human rights] issues. So, when Amnesty International proposed this idea, we welcomed it. Disappearances in Sri Lanka is a mind bogglingly huge issue but it hasn’t received the attention and care it deserves. More than75,000 people [have been] disappeared and the culprits are still [out] there. In that context, [the poetry contest] is crucial even as a small gesture.

Today, this is how

it dawns:

the night still lingers,

the light’s expanse muted,

at this time;

to wake and step out

when the koel sings

from the branch of a well-side tree;

below the earth,

deep and broad,

the well

sleeps peacefully,

like my heart.

Today, this is how

it dawns.

Do not think

it will be such dawn again

tomorrow;

halfway through the night,

at the gate,

the deep growl of the jeep,

the clatter of boots;— from “Two Mornings and a Late Night”

2. Earlier this month, your fellow judge in the “Silenced Shadows” contest V.I.S. Wediwardena, was denied entry to Sri Lanka. Authorities refused him entry right after the the launch of his book Sekku Gona, a translation of three of his Tamil novellas into Sinhala. What do you make of the restrictions placed on Wediwardena?

I know the Sri Lankan government has a blacklist. I do not know why the present government is still scared of Tamil writers, artists, and poets. What I suspect is that even though there is a change in the government, the structural problems that Tamils have been facing — like [discriminatory] state machinery, [increased] militarization, [illegal] surveillance — are still very much intact. Most of the people who have committed war crimes and crimes against humanity are still part of the government. So the state machinery that maintains and facilitates Sinhalese Buddhist dominance is still very much there. As long as that is there, any kind of change at the top level is only a change in the appearance, not in the substance.

3. The “Silenced Shadows” contest is open to “Sri Lankans living in the country or who have emigrated,” according to its English-language rules. Some Tamils don’t identify as “Sri Lankan” due to the political connotations it has after decadesof state violence against Tamils. How would you respond to Tamils born in Sri Lanka who are uncomfortable participating in the contest because they don’t identify as Sri Lankan?

I have never identified myself as a Sri Lankan because my political activism started in 1972 when the state promulgated the new constitution and renamed Ceylon as Sri Lanka and we were all forced to become “Sri Lankans.” The state sponsored, nurtured, and facilitated “Sri Lankan” identity is exclusive. In the current understanding, “Sri Lankan” means a Sinhalese and to a great extent aBuddhist person who lives in Sri Lanka. It never included Tamils in terms of political representation, cultural representation, and even symbolic representation. Whenever you locate a Sri Lankan association, it will largely be Sinhalese. That is why, in most cases, you see Tamil organizations. That is one point I’d like to make strongly.

AT A JULY DEMONSTRATION IN JAFFNA, A TAMIL MOTHER HOLDS PHOTOGRAPHS OF MISSING DAUGHTER ALONGSIDE A SIGN READS, “WHERE IS MY MISSING DAUGHTER WHO IS IN THIS PHOTOGRAPH NEXT TO THE CURRENT PRESIDENT.” IMAGE BY TAMILWIN, COURTESY OF TAMIL GUARDIAN.

Second, in the context of the Amnesty International contest, in Tamil, Sri Lanka has always been referred to as “Ilankai” and “Ilankai Tamil” means Tamil from Sri Lanka. That is correct.But “Sri Lankan” is a problem. In my understanding, most Tamils will not accept being called “Sri Lankans.” But in this context, Amnesty International has used “Ilankai” in the Tamil language rules.

The term “Ilankai Tamil” is acceptable. There are also a large number of Tamil speaking Muslims and Tamils who live outside the North and East provinces of Sri Lanka who identify themselves as Muslims and Tamils from Ilankai.

4. As a result of freedom of speech issues under the PTA, does the panel of judges anticipate any concerns on the part of participants in Sri Lanka regarding their freedom to openly criticize the government in their poetry?

I think that’s a reasonable concern. I’ve been in touch with a lot of writers from Tamil, Sinhalese, and Muslim communities in Sri Lanka for the past months for a different project. One question I’ve been consistently and continuously asking them is, “How free are you to talk about, write about, discuss some of these crucial issues?” The answers I get from these communities are interestingly different. If I speak to a writer in Colombo, they feel much more free after the change in the government. In the case of Jaffna, although the situation has greatly improved, they’re still concerned about surveillance and the Sri Lankan government and military intelligence following them. So even though there’s some kind of opening up, the underlying fundamental issue of complete freedom of expression is not there. On the other hand, the Tamil writers are kind of used to this kind of scenario [and have been] for a very long time. I have used several pen names in the past years in order to hide my own identity. So we need to wait and see how many responses we receive from Tamil and Muslim writers in the North and East.

with a shudder

the doors of our house

spread open;

then

eyes half closed and tired

having studied

for the test next day,

in that night

we hear “their” call;

the howling wind

in our ears.

“Where he is?” they ask,

their broken Tamil

pierces the heart.

Speechless

stunned,

as we shake our heads

flung into the jeep

the running engine

still growling.

— from “Two Mornings and a Late Night”

A TAMIL WOMAN TEARFULLY HOLDS UP PHOTOGRAPHS OF HER DISAPPEARED LOVED ONES AT A DEMONSTRATION IN JAFFNA IN DECEMBER 2011. IMAGE COURTESY OF TAMIL GUARDIAN.

5. Another project that encourages creative writing as a way to discuss post-war society in Sri Lanka is Write-To-Reconcile. During her November visit to Sri Lanka, U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. Samantha Power said of the program: “And the lesson of the project is a crucial one: When we make efforts to know and listen to one another… [w]e will know that those other people are not different from us, or at least not that different. We will treat them, as we ourselves would hope to be treated, with dignity.” Does the “Silenced Shadows” contest have a similar role to play?

I’m not familiar with the [Write-To-Reconcile] program; however, any program or project on reconciliation should start from acknowledgment. So first it’s the responsibility of the perpetrators and majority community to acknowledge what happened to the Tamil people in the last stages of the war. Without that acknowledgement, nothing can move forward. I would be asking, “How are these programs facilitating acknowledgment?” That is the question I would be asking everyone.

I’m also asking if the government of Sri Lanka or any [of the country’s] southern civil society organizations are willing to show the “No Fire Zone” documentary. There is [now] a Sinhala version available. That would be an ethical, critical step in the direction of solidarity and acknowledgment. It’s not only a good documentary but also recorded our anguish. It would begin the project of acknowledgement. They could show this documentary to the Sinhalese public. So far, no one has initiated doing that.

The other thing is that the Sinhalese journalists and writers that acknowledged that what happened to Tamils at the end of the war was genocide are all in exile — [from the members of] Journalists for Democracy in Sri Lanka, [plus individuals including] Bashana Abeywardane, Manjula Jayawardena, and several others. They can’t even go back to Sri Lanka. They wrote in Sinhala and have contributed enormously to revealing what happened during the final stages of the war. There is only a small group of Sinhalese activists, writers, and artists that have really acknowledged what happened to the Tamil people. Gordon Weiss’ bookand Frances Harrison’s book have been translated into Sinhala. Recently a collection of Sinhala poetry, The Dead Island, was published in Sri Lanka. Every single poem is in solidarity with the Tamils. This is what I call acknowledgment — very small progress in Sinhalese voices in solidarity with the Tamil struggle — small but very important.

6. This month, on Human Rights Day, Sri Lanka’s Foreign Minister Mangala Samaraweera announced that Sri Lanka would sign the International Convention on Enforced Disappearances. What are your thoughts?

I think this is a very important and necessary thing. I’m happy they’re doing that. There are all kinds of other U.N. treaties [that Sri Lankan officials] need to sign and ratify. They also need to overhaul the criminal justice system in Sri Lanka to address a lot of other issues. However, the one crucial difficulty is that, in the past thirty years, the Sri Lankan state has become so powerfully militarized. Whatever the politicians and government want to implement, they will not be able to do it if the military objects to it. In a sense, we’re looking at some kind of parallel to Pakistan, where the military is not accountable to the parliament.

Slowly, the power of the military has become so strong and the prime minister, president, any of them — they are in a sense helpless in antagonizing the military. For example, there are decisions to release all the lands in Jaffna confiscated by the military to their rightful owners — but if the military says no, that is a no. Evidence of secret detention centers in Trincomalee was given to the prime minister. He asked the military commanders and they [essentially] said, “No we don’t have such things.” The prime minister then said to Tamil politicians, “I checked with the military and they said they don’t have [any detention centers].” This is going to be the case again and again when it comes to demilitarization and implementation of all kinds of things.

What then?

It is life

as usual.

The morning sun

on bare earth

above me

grass.

Sometimes coming home

wanting to announce

before opening the door,

turning aside

to hawk and spit,

from inside

the sound of amma’s cough.

I waited

to open the door.

The world outside

as before

lay calm.

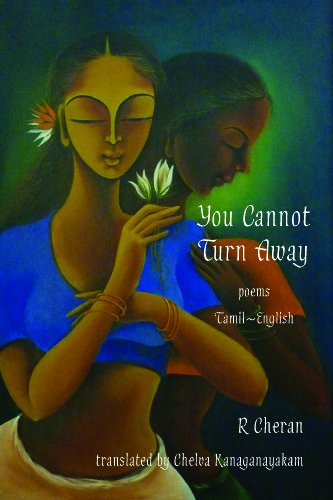

— from “Two Mornings and a Late Night” from You Cannot Turn Away,

translated by Chelva Kanaganayakam

7. Regarding your poem “Two Mornings and a Late Night” from the book You Cannot Turn Away, to what extent do you consider this poem and others you wrote during the war to be documentary works?

This poem narrates a true story of what happened to me as a university student. It was the first day when the government first enacted the Prevention of Terrorism Act in July 1979 and unleashed the military. They sent a commander from Colombo who was given a three month mandate to wipe out terrorism in Jaffna. He came and arrested […] people and killed them that night. We were university students at the time staying in a house near the university. We were all arrested but luckily none of us were killed. The PTA was declared in the morning; this happened that night.

Gowri Koneswaran is a Tamil American writer, performing artist, and lawyer whose family immigrated to the U.S. from Sri Lanka. Her poetry and peer-reviewed articles have appeared in arts and science journals. She is co-editor of Beltway Poetry Quarterly and senior poetry editor at Jaggery.