And RAW’s rascality in 1989

by Sachi Sri Kantha, April 2, 2023

Former Sri Lankan President Ranasinghe Premadasa’s (1924-1993) 30th death anniversary falls on May 1st. 15 years ago, I wrote about the puzzles of his assassination, alleged to be by the LTTE (but NOT proved legally!), in this website [https://www.sangam.org/2008/05/Premadasa_Assassination.php?uid=2906]. As such, for his 30th death anniversary this year, I will focus a little on Premadasa’s saber-rattling with Rajiv Gandhi, the then Indian prime minister during his first eleven months of tenure.

Ranasinghe Premadasa (1924-1993)

In the Govigama-caste dominated Sinhalese post-independent politics, Premadasa was an outsider. He was unlucky not to be born in the dominant Govigama caste. Barbara Crossette reported in the New York Times (Dec 21, 1988), ‘His family came from one of the nation’s lowest castes – the dhobis, or washermen.’ This needs some clarification. Two print reference source books on Sri Lanka on my shelf (Historical Dictionary of Sri Lanka, by S.W.R. de A. Samarasinghe and Vidyamali Samarasinghe, 1998, pp. 110-111; Encyclopedia of Sri Lanka, rev. ed. By C.A. Gunawardena, 2006, pp. 294-295), as well as digital Wikipedia, deftly omit this caste reference in their entry on Premadasa. I wonder why? One plausible reason is to promote a biased view that, Sinhalese are caste immune in comparison to Eelam Tamils.

As a pertinent aside, I provide a paragraph from the study of William Gilbert, entitled ‘The Sinhalese caste system of central and southern Ceylon’ [Journal of Washington Academy of Sciences, 1945; 35(4): 105-125] that covers the range of washer castes among the Sinhalese.

“The accounts concerning the washer caste are rather confusing in as much as the identity of the different washermen groups and their status relation to each other is not indicated. Apparently the Radaw (Henaya or Henawlaya) were the washers of the Goigama and other castes of high status such as sections of the Fishers, Toddy-drawers etc. Below the Radaw were at least three other washer castes, namely, (1) Hinniwo or Hinawa, who washed for Cinnamon-peelers primarily and also for Smiths, Toddy-drawers, Potters, Tailors, Fishers and Scavengers; Gangavo, primarily washers for Tree-cutters and Dancers; and (3) Pali, Paliyo or Apullanna, washers primarily for low castes such as lime-burners, palanquin-bearers, barbers, drummers, and jiggery makers. In addition, there appears to have been still another group of washers, the Tarumpar, who worked for outcastes. Thus it seems evident that the caste status of their clients was reflected in the status of the different washer groups.” [Note: words in italics, are as in the original.]

In reality, Premadasa was born in the minority hinniwo caste, who were traditionally laundrymen to another subcaste, Salagama (cinnamon peelers), lower in hierarchy to the Govigama caste. Premadasa also didn’t have tertiary education, in either Sri Lanka or anywhere else. But, he sharpened his street smart political instincts (including the art of fast draw, quick repartee in choice Sinhalese slang bordering on obscenity and back stabbing) to become the successor of J.R. Jayewardene in the presidential sweepstakes, despite strong challenge from guys with privileged background and education like Lalith Athulathmudali, Gamini Dissanayake and Ronnie de Mel. Eventually, Premadasa did win the presidential election against the SLFP matriarch Sirima Bandaranaike in late 1988, marginally with 50.4% of the votes cast, against Sirima’s 44.9%. To promote himself to his Sinhala voter base, Premadasa presented himself as a Buddhist patriot and strongly opposed the induction of the Indian army (under the guise of the Indian Peace- Keeping Force) by the Rajiv-Jayewardene deal of July 1987.

Premadasa’s political career has been studied by Rev. Josine van der Horst. Her 273 page book in English entitled ‘Who is He, What is He Doing? – Religious Rhetoric and Performances in Sri Lanka during R. Premadasa’s Presidency (1989-1993), published in 1995, deserves recognition for delving deeply into the mind of this flawed Sinhalese politician.

Premadasa’s mutilated body (source Newsweek, May 10, 1993, p. 7)

One of the unproved assumptions (strongly promoted by the Indian journalist hacks and politicians) in Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination by the LTTE in 1991, was that LTTE acted preemptively so that, if elected as the prime minister for the second time, Rajiv would send the Indian army again to Sri Lanka, to finish off LTTE. But, this assumption has a big hole. In 1991, the Sri Lankan president was NOT Jayewardene, but Premadasa, who had opposed the presence of Indian army in the island from mid 1987. That the same Premadasa would welcome Indian army again after 1991, simply because Rajiv had wished, would be nothing but a fool’s dream.

To prove my case of Premadasa’s antipathy to Indian army, for digital record, I provide below 12 unsigned news reports from the Economist weekly in 1989, collected in my files. The captions given are as in the original. These provide the early (sometimes erroneous) first draft of a vital segment of recent history of Eelam Tamils, as well as that of Rajiv Gandhi’s bungling in his job and his loss of popularity among the Indian masses in 1989. He would lose his prime minister position in November 1989, after five years in the job.

Especially of significance was the item recorded in the Aug 5, 1989 issue, when Premadasa, as commander-in-chief of the Sri Lankan army, was snorting to have a limited confrontation with the Indian army, while his Sinhalese army commanders “vetoed any confrontation, limited or otherwise.” This thigh-shaking response from Sri Lankan military’s grandees, though LTTE had been courageously confronting the IPKF for nearly two years, indeed deflated Premadasa’s braggadocio. One may infer now, that by offering an equal opportunity to his Sinhalese army commanders to confront the Indian army, that Premadasa indeed respected and honored Prabhakaran’s valor in leading LTTE’s small army for standing up to the bullying of Indian decision makers.

I did mention above that some of the early drafts of history by journalists are ‘erroneous’. Here is an example. The assassination of the then TULF leader A. Amirthalingam and his junior pal V. Yogeswaran on July 13th 1989 was erroneously attributed to the LTTE. Subsequent investigations by the LTTE and analysis of simultaneous political events pointed the accusing finger towards India’s intelligence agency RAW’s rascality. They had trapped the then No. 2 of LTTE (Gopalaswamy Mahendrarajah aka Mahattaya, 1956-1994) as their mole in 1989, and used Mahattaya’s relays as gunmen to finish off TULF leaders Amirthalingam, M. Sivasithamparam and Yogeswaran. Sivasithamparam was lucky to survive this ordeal. As the assassins also lost their lives, their mouths were permanently sealed. I had deduced this RAW rascality and presented my inference in the Pirabhakaran Phenomenon book (2005, chapters 21 and 22). Eventually it did receive positive confirmation 11 years later from Indian journalist Neena Gopal (The Assassination of Rajiv Gandhi, Penguin Random House, India, 2016, pp. 146-169). Mahattaya was caught for this treachery and paid for his sin of colluding with the RAW. The real conspirators who plotted the assassination of Amirthalingam and Yogeswaran were nameless RAW gumshoes though they had used Mahattaya’s hand-picked conduits as the assassins. The motives of RAW operatives for this deed were two fold: (1) to spite Premadasa, for his audacity in demanding the re-call of IPKF from the island. (2) to create confusion among Eelam Tamils and make them distrust LTTE. On the issue of Amirthalingam’s assassination and its RAW connection, apart from the details provided in my 2005 book, I also had written previously in 2018. [Please check this link. https://sangam.org/amirthalingam-mgr-raw-revisited/]

Despite these later revelations (especially by Neena Gopal, the editor of Deccan Chronicle in 2016), in pandering to the posthumous pseudo-interest of Sinhalese on Amirthalingam, journalist D.B.S. Jeyaraj persists in his twisted version that Amirthalingam and Yogeswaran were killed solely by LTTE operatives [check Daily Mirror, July 13, 2019 https://www.dailymirror.lk/opinion/How-LTTE-murdered-senior-Tamil-leader-Amirthalingam-30-years-ago/172-171054]. His version totally ignores RAW’s rascality as the prime conspirators, who manipulated Mahattaya. Jeyaraj remains a master in providing minute trivia, but obliterating the big picture or fundamentals.

12 unsigned news reports from the Economist weekly in 1989

Sri Lanka – Whose revolution will it be? Economist, Feb 11, 1989, pp. 34 and 36.

Sri Lanka – Blood, toil, tears and onions. Economist, June 10, 1989, p. 32.

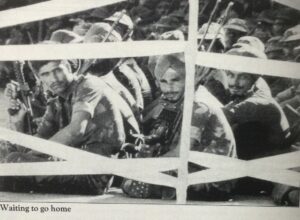

IPKF men waiting to go home (Economist, Sept 16, 1989)

Sri Lanka – Riding the tiger. Economist, July 1, 1989, p. 29.

India and Sri Lanka – On with the hunt. Economist, July 8, 1989, p. 31.

Sri Lanka- Too bad to print. Economist, July 15, 1989, p. 36.

Sri Lanka and India – Towards midnight. Economist, July 22, 1989, p. 31.

India – Gunning for Gandhi. Economist, July 29, 1989, pp. 31-32.

Sri Lanka – Time for Tea. Economist, Aug 5, 1989, p. 33.

India and Sri Lanka – Do or Die. Economist, Aug 26, 1989, pp. 25-26; and Murder most foul, Economist, Aug 26, 1989, p. 26.

Asia – The gun that can kill at four years’ range. Economist, Sept 9, 1989, pp. 35-36.

Sri Lanka – Agreed on a phoney peace. Economist, Sept 16, 1989, p. 32.

India – In the soup over Bofors. Economist, Oct 14, 1989, pp. 37-38.

Additional details which have been forgotten now also emerge from these Economist reports, written in 1989. These include, (1) forcible conscription of ‘some 15,000 young Tamils by the EPRLF group, that sided with the Indian government, in the governance of the combined North-east Provincial Council. (2) proclamation of a phony ‘unilateral declaration of independence’, which even LTTE was not thinking of at that time. (3) On July 14th 1989, Sri Lankan army shot and killed 4 IPKF men on patrol, in a village near Vavuniya, mistaking them for LTTE men. (4) W.J.M. Lokubandara, who would later become the Speaker of the Parliament from 2004 to 2010, was identified as ‘a religious zealot’, whose idea was “that newly recruited teachers in Sri Lanka should produce certificates from their parents stating that their children ‘worship’ the parents every day.”

Item 1: Whose revolution will it be? [Economist, Feb 11, 1989, pp. 34 & 36]

‘Please write something nice about us,’ says a government official weary of Sri Lanka’s woeful reputation for self-destruction. Very well. The shops and banks are open, the buses and trains are running again, there is petrol in the pumps, the curfew has been lifted. Many in Sri Lanka, where ‘auspicious days’ decide the movements of people from the president downwards attribute the present relaxed mood to an unusually favourable arrangement of the planets. An earthier view is that Sri Lanka seems to be pausing for breath between its presidential election of last December and the parliamentary election due on February 15th. Perhaps, the optimists are saying, Sri Lanka’s troubles can at last be settled by talk instead of violence.

This optimism manages to survive a daily battering as some new atrocity is reported. The most dangerous occupation in Sri Lanka is that of parliamentary candidate. By the middle of this week 12 of them had been shot dead and many of their supporters had died in the crossfire. These murders, however, appear to be mainly the result of personal animosities and party rivalries rather than the work of terrorist groups, although it has sometimes been expedient to blame the terrorists. The Tamil Tigers and the JVP (Janata Vimukthi Peramuna, or People’s Liberation Movement), the two main groups that believe the way to a better future is to kill people, are lying low.

This is of little comfort to the bereaved, but it cheers up everyone else. If only the Tigers and the JVP can be persuaded to keep quiet, business will boom, the universities will reopen and the tourists will return, lured once again by travel articles about sun-kissed beaches and the ancient frescoes of bare-breasted ladies in Sigiriya. ‘The tears of grief will turn to tears of happiness,’ says President Ranasinghe Premadasa.

Indian troops in Jaffna, Asiaweek Feb 19 1988

es, it is easy to get carried away. The reality is that Sri Lanka has a range of mind-splitting problems. It has the now famous problem of the Tamils who want a separate state in the island; the problem of the majority Sinhalese who have come to hate the Tamils; and the problem of what to do with the 45,000 Indian soldiers whose presence in Sri Lanka is resented by Tamils and Sinhalese alike.

Many Sri Lankans, probably most, blame India for all their troubles. From the early 1980s India supported the Tamil independence movement and allowed Tamil guerrillas to train in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu. In 1987 India persuaded the Sri Lankan government to grant the Tamils limited self-rule in the north-east. Indian soldiers were allowed in as a ‘peace-keeping force’ but were soon fighting those Tamils who continued to demand an independent state. An anti-Indian movement sprang up in the Sinhalese south. Its most violent expression is the JVP. Call it the Jolly Vicious Party, says a Sri Lankan with a taste for black humour. In little over a year it has killed more than 700 supporters of the government. Their offence, the JVP says, was that they allowed India, a traditional enemy, to invade Sri Lanka.

Get rid of the Indian soldiers then? If they go, the Tigers, a subdued but far from beaten force, will come out of the jungle and resume their fight for the state they call Tamil Eelam. The Sri Lankan army is not reckoned strong enough to replace the Indians. Mr Premadasa says the Indians will go but has not said when. Although he was prime minister in the government of the previous president, Mr Junius Jayewardene, he has managed to distance himself from the deal that Mr Jayewardene did with India.

The JVP, which tried to kill Mr Jayewardene, has spoken approvingly of Mr Premadasa. The Sinhalese guerrillas claim they helped him to power. Their threat to kill voters prevented the high poll that would have helped the main opposition candidate, Mrs Sirimavo Bandaranaike, whose government put down a JVP uprising in 1971. In the JVP view, Mr Premadasa will prove to be a weak president unable to cope with the revolution it judges is close. When he falls, the small group of well-educated and ruthless young people who control the JVP believes it will take over the country.

Nonsense – maybe. Mr Premadasa’s supporters claim he is strong, even ruthless. They note that during the presidential campaign he cruelly cold-shouldered Mr Jayewardene, his former mentor, in order to demonstrate that he is his own man. But Mr Premadasa’s own thinking coincides with the JVP’s on one point: he believes that unrest starts with poverty. He plans a revolution of his own. He is promising more than 1.4m poor families a gift of 2,500 rupees ($80) a month for two years. This is a lot of monwy in Sri Lanka. A factory worker in a free-trade zone gets 1,000 rupees a month.

Each year, this handout would equal at least half and possibly all of the government’s present yearly revenues, depending on how the largesse was distributed (under one plan part of it could not be drawn until the end of the two-year period). The president’s advisers propose less apocalyptic ways of helping the poor, but he appears to be unshiftable. He recalls that he grew up in a poor family to whom a lump sum such as this would have been salvation, the means to start a small business. That is what he is promising his people. If necessary he will simply print the money. Economics is not Mr Premadasa’s strong suit.

The International Monetary Fund is already frowning. The second instalment of a loan agreed to last year is due to be given to Sri Lanka in March. If this is withheld it will cast a cloud over an aid meeting in June arranged by the World Bank.

Under the Jayewardene government the country became self-sufficient in rice and substantially increased its export earnings, mainly from textiles and tea. But Sri Lanka still has to count on the generous charity of overseas friends. The former finance minister Mr Ronnie de Mel, who fell out with Mr Jayewardene last year, was the wizard who kept the aid flowing in. Mr de Mel, who (unlike the new president) is economically literate, might have been able to persuade Mr Premadasa of the vices of his plans. If not, even he would have found it impossible to persuade donors to keep writing cheques.

The paper kits are flying cheerfully over the green on Colombo’s seafront. The splendid Buddhist temple in Kandy has a new roof of gold. It is not difficult to find pleasant things to say about Sri Lanka. Alas, they are mostly superficial ones.

****

Item 2: Blood, toil, tears and onions [Economist, June 10, 1989, pp. 32]

Sri Lanka said go. India said no – at least not yet. President Ranasinghe Premadasa’s marching orders to the Indian soldiers occupying the north and east of Sri Lanka have not only worsened relations between the two countries; they may have further divided the island’s people.

The president’s demand on June 1st for the withdrawal by the end of July of the 45,000 Indian soldiers still in Sri Lanka caused dismay among those Tamils who regard the Indians as protectors against both the majority Sinhalese and the Tamil Tiger guerrillas Unlike the Tigers, other Tamil groups have abandoned the demand for a separate state, settling instead for a council in the north-east with limited autonomy.

Elsewhere in the country, Sinhalese nationalist groups have given enthusiastic support to Mr Premadasa’s demand. They have been insisting that the Indian ‘invasion’ which began in July 1987 be ended and Sri Lanka’s sovereignty restored. Anti-Indian feeling among the Sinhalese runs high. A bomb was thrown into the Indian High Commission in Colombo on June 2nd.

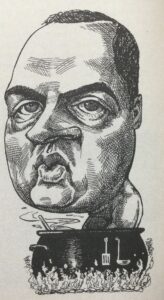

Rajiv Gandhi caricature (Economist, Oct 14, 1989)

The Indians were puzzled and angry. They had come to Sri Lanka under an agreement signed by Mr Rajiv Gandhi and Sri Lanka’s then president, Mr Junius Jayewardene, to disarm the Tigers and monitor elections for the new provincial council. The council is functioning, but so are the Tigers. In 20 months of fighting, more than 900 Indian soldiers have been killed and 2,500 wounded. The Indians had quietly accepted that it was now time to go; 12,000 have left since January. The rest might well have gone by the end of the year. The Indians said it was not possible to move 45,000 troops and their equipment, including heavy artillery, out of Sri Lanka in eight weeks. Why then was Mr Premadasa asking the impossible?

His critics say that this is the typically rash move of a man who pulls his policies out of a hat. Mr Premadasa is impatient for a success which will lift his presidency from its early slough of unpopularity. His anti-poverty programme has been stalled by its own absurdity (its first version would have added more than 50% to the already huge government budget deficit). Rising prices are hitting all sections of the population, and Mr Premadasa’s attempts to establish new moral standards please only the puritanical. But getting rid of the Indians is something the vast majority of Sri Lankans believe in.

There is an alternative theory. The Tamil groups which accepted the 1987 agreement fear that the president’s speech was prompted by a secret deal between the Tigers and the government. The two sides recently met for peace talks in Colombo – the first time they had sat down without Indian mediation in the 17 years of the Tigers’ guerrilla campaign. The other Tamils suspect that the government struck a bargain with the Tigers to dissolve the council, give them control of an interim administration and let them liquidate the other Tamil groups once the Indians have gone. The Tigers in return would promise not to harm Sinhalese and Muslim civilians.

Frightening if true. It is lent credibility by the fact that Mr Premadasa is increasingly worried about the plans of a Sinhalese extremist group known as the JVP (for Janata Vimukthi Peramuna, or People’s Liberation Front). The Front has called for a boycott of Indian goods and given warning to all Indian nationals with honorary Sri Lankan passports to leave the island by June 14th. Mr Premadasa believes that this warning is a thrust against not only India but also his government, which, the JVP says, should be overthrown for its betrayal of Sri Lanka to the ‘Indian imperialists’.

The government is so anxious to show that it is not pro-Indian that it has officially renamed two popular vegetables. Bombay onions, which are mainly grown in Sri Lanka, are to be called Sri Lanka big onions. Mysore dal, which are lentils from Turkey, will be known as red dal. Mr Premadasa, a man who claims to know his onions, hijacked the JVP’s main rallying call in his June 1st speech: ‘If we continue to keep a foreign army, it will be an act of treachery perpetrated on our country.’

Mr Gandhi may view Mr Premadasa’s words as an act of treachery. The Indian government has said its army is there by invitation and would leave when requested. Here was the request. But this is an Indian election year and compliance with the Premadasa timetable could spell trouble for the ruling Congress Party.. India would be making an undignified retreat. The Tamil groups it was leaving behind would have to be rearmed to defend themselves against the Tigers. This would mark a return to the killing days before India intervened. The whole Sri Lankan episode would have been a waste of lives, money and time.

So India will stay a while. It is likely to say that it has to see that the terms of the agreement are carried out – meaning fulfilling its duties as a gurantor of law and order in the Tamil areas – before it can leave. If it significantly outstays Mr Premadasa’s demanded departure date, support for the JVP could rise. In which case the president’s speech will have backfired and he – and Sri Lanka – will sink deeper into trouble.

*****

Item 3: Riding the Tiger [Economist, July 1, 1989, p. 29]

A couple of weeks ago, when the government of President Ranasinghe Premadasa asked India to get its 45,000 troops out of Sri Lanka by the end of July, it seemed to be saying, ‘Let us fight our own battles!’ This week it tried a different tack: ‘Look! We’ve stopped fighting. Now leave us in peace.’ That was the message behind the announcement on June 28th that the Tamil Tiger guerrillas were ending their 17-year old war against the Sri Lankan government. This is, in fact, a grim turn of events. It threatens to end in a serious confrontation between India and its small neighbour and in even more bloodshed in Sri Lanka itself.

The Sri Lankan government and the Tigers issued a statement saying they had agreed on an end to hostilities. Everything from now on could be decided by peaceful negotiation. Everyone – Tamil, Sinhalese or Muslim – should rally around Mr Premadasa’s call for a complete Indian withdrawal by the end of July. On the same day India made its response to his request: it said no. But the agreement between the Tigers and Mr Premadasa’s government will present India with a sore test.

Afterall, its peacekeeping force came to Sri Lanka in 1987 with the purpose of separating the Sri Lankan army and Tiger guerrillas, who were bitterly fighting each other in the northern Jaffna peninsula. India sent Sri Lanka’s soldiers back to their barracks and then staged a series of offensives against the Tigers when they refused to lay down their arms. Now that the Tigers have agreed to surrender the gun, what reason is there for India to stay?

The hard-boiled reason is that Mr Rajiv Gandhi, India’s prime minister, is not about to let himself be humiliated in an election year by recalling his troops too hastily. The statesmanlike reason is that India’s troops have become more than a simple peacekeeping force. They are the Tigers’ implacable enemy, the only force that has shown itself capable of keeping the guerrillas at bay. And India has become the protector of the formerly separatist Tamil groups – notably the Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front (EPRLF) – that have had the courage to go along with the peace plan for the north and east of the island.

Remove the Indians and Sri Lanka could fall apart. The EPRLF is becoming convinced that Mr Premadasa’s government has made a deal to let the Tigers liquidate it once the Indians go. It has declared that it wil make a unilateral declaration of independence the moment the provincial council for the north and east, which it controls, is dissolved under the terms of this week’s agreement between the Tigers and the government. Already, some 15,000 young Tamils have been forcibly conscripted by the EPRLF for training in Indian camps.

The EPRLF has good reason to fear what is increasingly looking like a devil’s pact between Mr Premadasa and the Tigers. Above all, the Tigers want the Indians out. More than 900 Indian soldiers have died fighting during the past 20 months, but the Tigers have lost more than 500 from a much smaller force. Once the Indians have gone, the Tigers will be able to resume the war at will.

For his part, President Premadasa needs to relieve the pressure being put on him by the People’s Liberation Front (JVP), an extreme Sinhalese nationalist group. The JVP, which says the government betrayed Sri Lanka by letting the Indians in, has brought Sinhalese areas of the country to a standstill with strikes and sabotage.

The president encouraged by popular support for his stand and ignoring the advice of his wiser ministers, is heading for a collision with India. He has ordered Indian troops on the island confined to their barracks after the end of July. He has told his foreign minister to boycott a meeting of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation to show his displeasure with India. After this Tiger ride, more than just Mr Premadasa are likely to end up inside.

*****

Item 4: On with the hunt [Economist, July 8, 1989, p. 31]

In the end, he could not insist. Sri Lanka’s President Premadasa has backed down from his demand that the Indian peacekeeping force should leave the island by the end of July. In a letter on July 3rd to the Indian prime minister, Mr Rajiv Gandhi, he said he was prepared to discuss the timetable for the withdrawal. He had little choice, India having made it clear that it was not going to be hustled out of the country. Mr Gandhi spared Mr Premadasa further humiliation by agreeing to a ‘time frame’ for bringing the soldiers home. But the Indians are determined to destroy the remaining Tamil Tiger guerrillas before they go. This week they went into the northern jungles in force in an operation codenamed ‘Storm’.

India has been disturbed by reports that the Premadasa government has done a deal with the Tigers, promising them a free hand in the north-east against other Tamil groups who have laid down their arms. These Tamils support the North-East Provincial Council, which has been given a degree of autonomy. If the Indians went while the Tigers were still active, the council’s members would almost certainly be killed.

Mr Gandhi’s refusal to pull out at once is not just because he does not want to retreat in an Indian election year. The past month has been a closing of ranks in India behind the government on this issue. In particular, Mr Gandhi now has the support of the chief minister of Tamil Nadu, the home of India’s 55m Tamils. The chief minister had been a virulent critic of Mr Gandhi’s policy, accusing the prime minister of seeking Indian hegemony throughout South Asia. But on July 2nd, fearing a bloodbath if the Indian army left, he asked Mr Gandhi to ensure the safety of Tamils in Sri Lanka. India’s opposition coalition, which had previously called for an immediate withdrawal from Sri Lanka, has now dropped this demand.

Indian intelligence reports now even accuse the Premadasa government of arming the Tigers, on the ground that they both have an interest in getting the Indians to go. The Tigers have suffered heavy casualties at the Indian army’s hands. Mr Premadasa thinks that removing the Indians would appease the People Liberation Front, the passionately nationalist Sinhalese group fighting the government in southern Sri Lanka.

Mr Premadasa may find his new found Tiger friends hard to deal with. In a letter to the president, written on June 30th, Mr Gandhi asked if the Tigers had given up their aim of a separate state in Sri Lanka, and whether they had promised to renounce violence. Mr Premadasa could not say. In a radio interview the Tigers’ principal negotiator, Mr Anton Balasingham, said they had no intention of laying down their arms. Mr Premadasa’s move has caused uneasiness within his own party. Three of his ministers have spoken against a hasty pullout by the Indian soldiers.

Mr Gandhi has halted the staged withdrawal that began last October. So far some 9,000 troops have returned to India. No more will come back, India says, until the Tigers, or what remains of them, give credible assurances of an end to the violence in northern Sri Lanka. Given the Tigers’ record of broken promises, India will need a lot of persuading.

*****

Item 5: Too bad to print [Economist, July 15, 1989, p. 36]

The catchphrase President Premadasa has loved to use since he took up the leadership of Sri Lanka six months ago is ‘compromise, consultation and consensus’. It has been ignored. Last week he was forced by growing chaos to add a fourth C – crackdrown.

The president has been unwilling to admit that Sri Lanka is in crisis; indeed, in several crises. The Indian expeditionary force is refusing to go home until it has subdued the Tamil Tiger guerrillas. Other Tamils, opposed to the Tigers, are threatening to declare an independent state in the north-east of the country because they suspect that Mr Premadasa has done a deal with their Tiger enemies. In the south, the People’s Liberation Front, a Marxist-nationalist group which hates both the Tigers and the Indians, has renewed its campaign of strikes and unrest in its attempt to overthrow the government. And, by the way, the economy is in imminent danger of collapse.

On July 6th all the measures that were used last November to cope with the previous onslaught by the People’s Liberation Front were brought back with a vengeance. Anyone pasting up posters – the Front’s main publicity technique – can be shot on sight. Public meetings have been banned. Anyone staying away from work will be served with a detention order. All news stories for domestic or foreign consumption have to pass through an unbudgeable censor. Reports on violence, the state of emergency the transport strike or the Indian withdrawal are banned.

Mr Premadasa is careful about his own publicity. He has not granted an interview to a journalist in more than ten years. He is described by his government’s spokesmen as a kindly, pious and humble servant of the people. Whatever the truth of that, the rumour-mill says his cabinet is terrified of him and that he treats dissent as disloyalty. Now he is trying to establish what he calls his New Vision, based on a yearning to make Sri Lanka a more moral place. Mr W.J.M. Lokubandara, a religious zealot, has been put in charge of the government’s morality programme. One of his ideas is that newly recruited teachers in Sri Lanka should produce certificates from their parents stating that their children ‘worship’ the parents every day.

The president’s right-hand man is Mr Ranjan Wijeratne, a planter who has never served in government before but is now foreign minister. President Premadasa himsels has been impetuous and naïve in dealing with the economy, foreign policy and internal security. His call in a speech on June 1st for Indian troops to leave by the end of July was made without first telling India or his own foreign ministry. It has made an enemy of Sri Lanka’s giant neighbour.

In matters of state housekeeping, the president has adopted a ‘spend, spend, spend’ policy. Civil servants have had pay rises, and more money has been allocated to his poverty-alleviation programme than to defence. Inflation is unofficially estimated at around 30% and likely to rise. The People’s Liberation Front notes that poor families are being promised 2,500 rupees ($80) a month and is demanding similar wage increases all round. Sri Lanka faces an uncomfortable meeting with the International Monetary Fund in the autumn to explain its sharp deviation from the Fund’s guidelines.

The government may take some comfort. Colombo’s port was working again this week; freight was being moved, some buses and trains were running, and people were turning up for work in large numbers. But there is still no sign that the People’s Liberation Front will halt its campaign of chaos. The regional government of the north-east is conscripting young men into a defence force for the separate state it threatens to create. President Premadasa continues to recite ‘compromise, consultation and consensus’. Yet, even in a mainly Buddhist country, such mantras have a modest effect. They do not melt the hearts of Hindu Tamil separatists, Hindu and Muslim Indian soldiers, nationalist revolutionaries – or the IMF.

At the end of this newsreport, there was a box item that stated, “News from Sri Lanka is being heavily censored. This report has been put together in London from various sources.”

*****

Item 6: Towards midnight [Economist, July 12, 1989, p. 31]

Little Sri Lanka considers itself to be close to war with its neighbor India. On the night of July 14th an Indian army patrol entered a Sinhalese village near Vavuniya in northern Sri Lanka. The village was guarded by Sri Lankan soldiers. Firing broke out and four Indians were killed. The Sri Lankan army said its people had been attacked. The Indians said their men had been mistaken for Tamil guerrillas raiding the village.

The ‘mistake’, if that is what it was, could be repeated, perhaps many times, after July 29th. By then, says Sri Lanka’s President Ranasinghe Premadasa, the Indians should have gone home. Any who remain he will confine to barracks, using his authority as commander-in-chief of all forces on Sri Lankan soil. Sri Lankan soldiers will then take over from India responsibility for the security of the North-Eastern Province, where the Tamil Tiger guerrillas seek to impose their own rule.

It is unlikely that the Indians will obey his order. They have made it clear that they wil not be hustled out of Sri Lanka, to which they were invited as a peacekeeping force under an accord signed in 1987. So two armies could be roaming the region, each claiming it as its own territory.

No political compromise is in sight to end this alarming prospect. The assassination in Colombo on July 13th of Sri Lanka’s leading Tamil politician, Mr Appapillai Amirthalingam, who preached non-violence, shocked not only Sri Lankans but also the 50m Tamils of the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu. The Tigers were apparently responsible for this killing and possibly that of Mr Uma Maheswaran, leader of another Tamil group, three days later.

India’s prime minister, Mr Rajiv Gandhi, argues that the Indian army must stay on to ensure the security of Tamils. He is anxious to protect those Tamil groups that have defied the Tigers by accepting the limited autonomy granted to the north-east, where most Tamils live. ‘We have given out word that we shall guarantee their security,’ he said this week.

Mr Gandhi’s stand is winning patriotic support in India, and will do him no harm at all in the general election due in less than six months’ time. Mr Premadasa, too, now has a popular issue to draw attention away from his other troubles: the collapsing economy and the political killings by the Tigers and the Marxist-nationalist People’s Liberation Front. In the latest attack, this week, 13 people died in southern Sri Lanka when grenades were thrown at a religious procession.

Neither leader has right entirely on his side. Mr Premadasa, unreasonably and without prior consultation, asked the Indians to leave by the end of July when they had already agreed to go by the end of the year. But India, whatever it may feel about its moral duty towards the Tamils, has no right to remain in Sri Lanka, a soverign state, when it is told to go. With 45,000 Indian troops obstinately entrenched on Sri Lankan soil, it is five minutes to midnight.

*****

Item 7: Gunning for Gandhi [Economist, July 29, 1989, pp. 31-32]

The prime minister of India is turning out to be the opposition’s best friend. A week ago Mr Rajiv Gandhi’s Congress Party seemed to set to win the forthcoming general election, now at most five months away. The opposition, a National Front made up of regional parties and some smallish national ones, and led by Mr Gandhi’s former finance minister, Mr Vishwanath Pratap Singh, was deeply divided.

This week the opposition was united. All its members in the lower house of parliament were in the process of resigning their seats. It was an unprecedented show of solidarity involving the entire opposition, from the Hindu right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party to the Communist Party of India (Marxist). On July 24th 73 opposition members resigned. The remaining 35, most of whom were away from Delhi, were expected to follow suit.

The protest was intended to draw attention to a corruption scandal. In 1986 the defence ministry decided to buy guns made by Sweden’s Bofors company in preference to French guns that had been the army’s original choice. India’s auditor-general was asked to report on the transaction. His report was ready in March, but Mr Gandhi delayed its presentation until last week. He then declined to attend parliament to answer questions the report raised.

The report notes ‘grave irregularities’ in the way the guns were bought. It thus gives indirect support to an allegation that Bofors had been chosen to supply the guns mainly because of the kickbacks it had promised to a host of intermediaries, some of them close to the Congress party. Mr Gandhi was defence minister as well as prime minister when the deal was signed.

In parliament members of the Congress party abused the auditor-general. One former minister said the wretched official should be ‘kicked in the bottom’. Members of the opposition responded by saying the Congress party was arrogant, and had dwindling regard for democratic institutions. Then they walked out.

Until last week Mr Gandhi had managed to push the issue of corruption aside. Now it is back in the headlines. His careful wooing of the voters – by such things as lowering the voting age to 18 and creating elected village councils – may turn out to be a wasted effort.

Mr Gandhi’s election timing may also have gone wrong. It was thought he had decided to hold the election two months ahead of schedule, at the end of October or the beginning of November. By demanding an immediate election the opposition has upstaged him. The prime minister must now choose between going for an early election, as the opposition demands, or dragging out the life of the rump parliament until the last possible day, hoping that things will start going his way again.

If he delays, his aim will be to try to shift the voters’ gaze back to his reform programme. One part of this programme consists of changes to the election system for agricultural co-operatives. These co-ops particularly in sugar, cotton and some other cash crops, wield enormous influence over farmers’ lives. Their lack of accountability has turned them into the private preserves of party bosses in the states. Mr Gandhi might push a co-op reform bill through parliament in the hope of repairing at least some of damage to his party.

He may also play the patriotic card. By midweek Mr Gandhi had yet to respond to the letter from Sri Lanka’s President Ranasinghe Premadasa offering to compromise on his earlier demand that India withdraw its 45,000 troops from the island. Indian soldiers had been moved to the south of India and an aircraft carrier sent to the waters near Sri Lanka. It could prove an interesting end of July both for Mr Gandhi and for those who would unseat him.

*****

Item 8: Time for tea [Economist, Aug 5, 1989, p. 33]

It was to be the day when the last Indian soldier left Sri Lanka. That country’s President Ranasinghe Premadasa had demanded it in a speech back in June. The Indians must go by July 29th, he said, the second anniversary of the arrival of the troops sent in to help bring peace to the island.

In the event only 600 Indians left, out of the 45,000 stationed in Sri Lanka. Even their departure aroused doubts. A ragbag of paras and men from the artillery corps boarded a troop carrier in the north-eastern port of Trincomalee with little of the formal ceremony expected of such a departure. They looked like assorted soldiers taking a few days’ leave rather than a unit going home, its job finished.

Sri Lanka’s state-run television and newspapers made the best of it, hailing the withdrawal as a ‘great victory’ for the president. In fact it was the sad climax to an ill-thought-out demand by Mr Premadasa. Had he said nothing, the chances are that India would have withdrawn 22,000 of its troops by now. That was its plan. India does, it seems, want to get out, but at its own pace and with dignity. President Premadasa has made the pullout an issue of stubborn pride between the two countries.

He has correctly assessed the attitude of Sri Lanka’s Sinhalese majority towards the Indians: they dislike having them in the country. In the south the nationalist extemists as the JVP are trying to bring down the government on the patriotic issue of the Indian ‘invasion’. Then there are the Tamil Tigers, who for 17 years have been fighting for a separate state in the north-east of the island. Mr Premadasa believes he can control the Tigers, if the Indians will stop hunting them down.

The president, as commander-in-chief of the Sri Lankan army, was apparently prepared to order his soldiers to confront any Indians still in the country after July 29th who had not confined themselves to barracks. A small-scale fight would win him Sinhalese support, and international sympathy for a small nation being bullied by a bigger neighbour. No way, said his army commanders, they vetoed any confrontation, limited or otherwise. Fifteen thousand ill-equipped Sri Lankan soldiers in the north-east were clearly unable to eject an Indian force three times their size. Sri Lankan officers were told by their commanders to invite their Indian counterparts into their camps for tea and a friendly chat.

All Mr Premadasa got in the end was India’s offer of a token withdrawal, together with talks to try to settle other matters. The talks, which took place in Delhi this week, have so far yielded nothing. India seems determined to keep at least some soldiers in Sri Lanka until it is satisfied that the Tamil dominated regional government it has helped to establish in the north-east is secure. India fears that Mr Premadasa wants to dissolve the region’s government and allow the Tigers a free hand there.

The JVP continues to harass Mr Premadasa. On July 28th it organized a big demonstration against the government. The security forces reacted brutally, shooting dead 129 people. The JVP’s power is growing. Its trade union arm can, and does, bring the country to a standstill. It is demanding ‘truth’ in the media and is believed to have been responsible for the murders of a broadcasting chief and a television presenter. It wants Sri Lankans to be told the JVP is here to stay and that it is doing its best to ensure that the government and the Indians are not around for much longer.

*****

Item 9: Do or Die [Economist, Aug 26, 1989, pp. 25-26]

For months Sri Lanka has been described as being on the brink of an abyss. But, as is sometimes said about Northern Ireland, the abyss gets moved. This week Sri Lanka and India were doing their best to give it a shove.

The two countries are in conflict about the soldiers India sent into Sri Lanka two years ago in what was seen at the time as a useful effort to bring peace to the island. Sri Lanka’s President Ranasinghe Premadasa now desperately wants the Indians to go. He has tried, without success, to order them out. Now he is pleading with them. Only their departure, he has told India, will enable him to retain his waning authority. The alternative is the collapse of civil government in Sri Lanka and its replacement by military rule.

India seems at last to be taking Mr Premadasa’s pleas seriously. To give him breathing space it has already withdrawn a token 600 of its 45,000 soldiers. Officials of the two countries meeting in Delhi this week have been discussing when the remainder might leave. India has suggested next February. Sri Lanka says they must go this month. December may be the compromise.

The Indian prime minister, Mr Rajiv Gandhi, is not going to be hustled, even by the tears of Mr Premadasa. He has a general election coming up and needs to protect the honour of the Indian army, which has lost around 1,000 men in Sri Lanka. Voters in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu would be aghast if India left Sri Lanka’s Tamils unprotected. India’s one success in Sri Lanka is the setting-up of a Tamil-run provincial council in the north-east. India fears that the Tamil Tigers, who want a separate state in the island, would destroy the council (and any Tamils who co-operated with it) if the Indian force were withdrawn too quickly.

In the Delhi talks India has been demanding guarantees for the council’s survival. The most practical gurantee would be a promise by the Tigers to give up their arms. This is so unlikely that India will have to accept a fudged guarantee if an agreement is to be signed. Fudging appears to be on the agenda. The agreement will propose that the Tigers be invited to sit on a committee that would appoint a force responsible for security in the north-east. This would show that the Tigers supported democratic processes. India, the Sri Lankan government and the north-east council would also be represented on the committee. India would pull out a unit of its soldiers at a time, leaving Sri Lanka to replace the Indians with a ‘trained force acceptable to the local people’.

Whether such an agreement saves Mr Premadasa’ skin probably depends on how he puts it over. In his favour is Sri Lanka’s longing for peace. More people have been killed, unpublicized, in Sri Lanka over the past five months than the 500 or so who have died during this time in Beirut. Most of the present killings are being blamed on the revolutionary group known as the JVP, which claims support from the Sinhalese majority. The JVP, which recently shot dead a number of television people, claiming, correctly, that Sri Lanka’s broadcasting stations support the government, has now threatened to kill soldiers’ families unless the soldiers resign. The soldiers havesaid that if this happens they will turn their guns on JVP families.

Against this dreadful background, Sri Lanka’s other problem, its near-bankcruptcy, looks refreshingly normal. Its foreign-exchange reserves at the end of July were barely sufficient to pay for two weeks’ imports (down from a 13-week cushion when Mr Premadasa took over in January). A team from the Internatioanl Monetary Fund arrived in Colombo this week, and seemed willing to release $89m of a loan agreed to last year. The money had been due in March, but the IMF was not then satisfied that Sri Lanka was sufficiently austerity-minded. The country, like it or not, is now in an austere mood.

Murder Most foul [a boxed item, in p. 26]

Poor Rajiv Gandhi. It is not enough that the Indian prime minister’s opponents accuse him of being incompetent and corrupt. They are trying to implicate him in a murder plot.

To begin, more or less, at the beginning, on August 1st the Bombay police arrested Mr Kirti Ambani, a senior executive of fast-growing Reliance Industries, India’s largest company. He was accused of being involved in an attempt to murder Mr Nueli Wadia, the chairman of a rival concern, Bombay Dyeing and Manufacturing. The published evidence against Mr Ambani is slender almost to the point of being invisible. According to the Bombay police, the underworld character who masterminded the would-be murder had Mr Ambani’s visiting card in his pocket. As for the motive or rather lack of it, Reliance is far too big to fear competition from Mr Wadia’s company.

The case seems to be political. Bombay lies in the state of Maharashtra. The chief minister is Mr Sharod Pawar. In 1976 he fell out with Mrs Indira Gandhi, the then prime minister, and returned to the ruling Congress party only in 1986. When Mr Pawar was made chief minister in 1988, it was on the understanding that he would not try to secure for his own nominees any of Maharashtra’s seats in the federal election due by this December.

Since then the Congress party has started looking weaker. Mr Pawar now wants his people to get Congress’s nomination for 38 of the state’ 48 parliamentary seats. Mr Gandhi has been advised to sack Mr Pawar as chief minister. Mr Pawar believes that the Reliance chairman Mr Dhirubhai Ambani, a friend of Mr Gandhi is behind this advice (the chairman is no relation to Kirti Ambani). The enthusiasm of the Bombay police to charge Mr Kirti Ambani is, it is generally believed, intended as a warning to Mr Gandhi to lay off Mr Pawar. Anyone who thinks such speculation too ludicrous to be taken seriously has scant knowledge of the strange ways of Indian politics.

The plot thickens. A leak from the Bombay police suggests that Mr Wadia was just one name on a hit list of 12, headed by Mr Gandhi’s main political opponent, Mr V.P. Singh. Mr Gandhi has taken a cool view of the affair, merely insisting that the case be investigated by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) and not the Maharashtra police. The plot thickens further. The Indian Express, a newspaper that supports the opposition and has ties with Mr Wadia, has alleged that the head of the CBI or rather his son, has business links with Reliance.

However that may be, Mr Pawar has formally acquiesced in the CBI taking over the investigation. Mr Dhirubahai Abmbani says that he believes Kirti to be innocent. He has made no comment on the political implications. He claims that the affair has been got up in order to abort Reliance’s share issue, the largest the country has known, which opened on August 4th.

*****

Item 10: The gun that can kill at four years’ range [Economist, Sept 9, 1989, pp. 35-36]

When the Indian government signed a contract in early 1986 with the Swedish company Bofors to supply $1.4 billion-worth of 155mm howitzer to the Indian army, Mr Rajiv Gandhi little realized that he might have caused his own and his party’s defeat in India’s next election. That election is now no more than three months away, and the prime minister hears the whistle of the approaching shell he himself fired all that time ago.

The Bofors howitzer is an excellent gun, which is serving India well. A lieutenant in the Indian army just back from the snowy wastes of the Siachen glacier up in the Himalayas, where India and Pakistan have been fighting an undeclared war for the past four years, tells your correspondent that earlier this summer it hit Pakistani targets, at extreme range over the top of the mountains, with ‘pinpoint accuracy’. It was grand for ‘shooting and scooting: it could thump away at the enemy and then move to a new position in less than the two minutes it took Pakistan’s American-made artillery-finding radar to locate it and direct the Pakistani guns on to the place where it had just been.

Money, not guns, is Mr Gandhi’s trouble. Ever since 1987, the year after the contract was signed, the story that Bofors had promised and paid huge kickbacks to unidentified Indian middlemen has surfaced with embarrassing regularity. Each time it has come up, many Indians have felt that it confirms their worst fears about corruption in the ruling Congress Party. As time has gone by the possibility has been raised that, even if Mr Gandhi did not take any of the kickbacks himself, he certainly knew about them and condoned them. Now comes the most damaging blow yet to his credibility.

General Krishnaswami Sundarji was the army’s chief of staff in 1986, and he endorsed the decision to buy the Bofors gun. But he has just declared, in an interview with the magazine India Today in which he expressed his relief at getting the matter off his chest at last, that he had strongly advised the government to threaten Bofors with the cancellation of its contract if it did not reveal the names of its ‘agents’. His advice had been ignored, he said, by the prime minister’s office.

This flatly contradicts Mr Gandhi’s assertion, which he has made more than once in the past two years, that he had thought of cancelling the Bofors contract, but had met stiff opposition from the army chiefs. What General Sundarji said sharpens the choice between the voters at the forthcoming election. They have to decide whether they will be ruled for the next fiveyears not only by a party that is palpably corrupt, but also by a prime minister who probably has not told the truth on this important subject. It is hard to see how Mr Gandhi and the Congress party can fail to be hurt by General Sundarji’s words.

The ordinary Indian has a strong moralistic streak. Most Indians still subscribe to values that predate the industrial revolution. For them trade is still a form of exploitation, and the charging of interest is usury. To these people, kickbacks and commissions on defence contracts amount to a betrayal of the nation. That Bofors was prepared to pay as much as 14% of the value of the contract to its ‘agents’ (and that its competitors were no doubt willing to do the same) has shocked most people. It puts a powerful new charge into the belief, long the subject of rueful gossip in Delhi’s drawing rooms, that huge commissions have been loaded on to virtually all large foreign contracts – not just defence ones – to help the finances of the Congress party.

Mr Gandhi came into office when his mother was assassinated in 1984, and handily won the ensuing election on the sympathy vote. In the following year, his popularity grew immensely because he showed every sign of wanting to make a break with the past. In March 1985 he reformed the system of direct taxation to encourage taxpayers to declare their incomes. In October of that year he ordered all ministries to eliminate middlemen in all large contracts. Two months later, during the celebration of the Congress party’s centenary, he delivered a tirade against corruption in the party and promised to clean it up. After all this, the disappointment caused by the Bofors revelations is acute. In a country like India, its effect on the Congress party’s chances in the election could be enormous.

The opposition is counting on it. It consists mainly of a severn-party coalition called the National Front. It does not have much to offer the electorate in the way of distinctive policies. But it does have as its leader a man most Indians consider to be honest. This is Mr Vishwanath Pratap Singh, Mr Gandhi’s former finance and defence minister. He was forced out of the government, and the Congress party, in 1987 because he had started an inquiry into kickbacks allegedly paid by a West German submarine-building firm in 1981, and also illegal accounts held by Indians in banks abroad.

Mr Singh has been campaigning vigorously for the past two years on the corruption issue. With the Congress party’s help he may at last have made his point stick. Until as recently as July it had seemed that Mr Gandhi was managing to divert attention from the subject. He had lowered the voting age from 21 to 18. He had also introduced a constitutional amendment to make elections to village councils mandatory, thus in effect creating a third tier to India’s federal democracy. These were popular measures.

He then undid all that good work. First, he tried to suppress the auditor-general’s report on the defence ministry, which made some critical observations about how the Bofors gun had been chosen in preference to it French competitor. He then allowed members of his party to attack the auditor-general in parliament. This gave Mr Singh the opportunity he had been looking for. The opposition resigned en masse from parliament. Mr Singh reinforced his anti-corruption credentials by announcing that, if he becomes prime minister, he will publish the details of all large contracts awarded by the government, and will st up a national fund to cover parties’ election expenses. The creation of such a fund was the one thing Mr Gandhi had left out of the electoral reform bill he put into force at the beginning of this year.

Mr Singh is looking at the 70m new voters in the 18-21 old range Mr Gandhi has enfranchised. He knows they are at the most idealistic stage of their lives, and he is appealing directly to them.

*****

Item 11: Agreed on a phoney peace [Economist, Sept 16, 1989, p. 32]

The seven Tamil groups taking part in this week’s ‘all-party conference’ on peace in Sri Lanka were told by the security guards at the meeting hall to leave their weapons outside. Meekly, they did. If only it were so easy in the country at large.

The day after the conference, Sri Lanka announced that an agreement was near under which India would withdraw its 40,000 remaining peacekeeping troops from the island by early next year. There may be last minute snags, but India will go. When it does, the conference’ strangely peaceful sight – Tamil Tigers sitting down with their arch-enemies of the Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front (EPRLF) and exchanging nothing more deadly than words – is sure not to be repeated. Instead, a fratricidal war is likely to break out in the Tamil north and east of the island, leaving the Sinhalese south, where much of today’s blood is being shed, in relative peace.

The Indians had long been planning to leave by January. Their soldiers had been set an impossible task when they went in back in 1987. They were to disarm the Tigers but not exterminate them. The Tigers, who had no interest in giving up the certainties of the gun for the vagaries of the ballot, melted into the northern jungles to be chased fruitlessly by the Indian army. More than 1,000 Indian soldiers have been killed. Morale among the Indians is low, and indiscipline is eating its way in. The Indian army’s massacre of 53 Tamil civilians in the northern Jaffna peninsula on August 2nd horrifyingly showed how far the rot has gone.

India’s plan for a dignified withdrawal was wrecked by the impetuous speech given by Sri Lanka’s President Ranasinghe Premadasa in June, in which he told the Indians to get out by the end of July. India naturally dug its heels in. Mr Premadasa naturally had to back down, and now, after a lot of haggling, the two countries are back to the original timetable.

Although he did not accomplish what he set out to do, Mr Rajiv Gandhi, India’s prime minister, is ready to withdraw because of the general election he faces late this year. Provided he is not seen to be forced out, he wants to leave his opposition is getting enough mileage out of ‘India’s great misadventure’ that he will be happy to be rid of it. For his part, President Premadasa stirred up the dispute with India in June to seize the nationalist initiative from the Sinhalese extremists known as the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (People’s Liberation Front). Now he realizes the JVP will seize on any old issue to continue its campaign – so why not let the Indians leave in the way they want?

The Indians will reflect bitterly on their experience. They came in, at Sri Lanka’s request, to bring peace. They leave behind not only their own corpses and those of the many Tigers they have killed, but thousands more civilians than combatants dead. The political solution has solved little. The north-eastern provincial council to which power was devolved has been boycotted by the Tigers and their backers, and though it was elected in freeish ballot it has never seemed to win legitimacy. India is resigned to a contest of force; it has been arming the Tigers’ rivals and allowing them to conscript fighters in the north-east.

The withdrawal agreement between India and Sri Lanka, which was expected to be signed over the weekend, will probably set up ‘peace committees’ comprising representatives of the Tamil groups and Sri Lanka’s security men. They are supposed to substitute for the Indians in preserving order in the north-east. Some peace committee: the Tigers have sworn not to co-operate with ‘Indian quislings’ like the EPRLF.

President Premadasa will be left with the hopeless task of trying to persuade the Tigers to lay down their arms when he restarts the Tamil peace talks that have been stalled for more than two months. For the moment, though he is feeling less beleaguered than he was during the massacre-ridden days of August. The JVP guerrillas look a little sicker after a ruthless crackdown by the security forces, and he now has new IMF money under his belt. His comfort promises to be brief: this is a phoney peace.

*****

Item 12: In the soup over Bofors [Economist, Oct 14, 1989, pp. 37-38]

Indians are uneasily aware that their political system is sustained by money from tax evasion, smuggling, bootlegging, protection rackets and other criminal or near-criminal activities. But there has been no proof. In the Bofors scandal, which took a new turn this week, there now does seem to be evidence of wrongdoing by Mr Rajiv Gandhi’s ruling Congress party. It is bound to be an issue in the general election now only two or three months away.

In 1986 Bofors, a Swedish arms manufacturer, sold the Indian army 400 155mm howitzers and the know-how to make the gun. The deal was worth $1.4 billion. Allegations have been made since 1987 that Bofors paid hefty bribes to a middleman to seal the deal, and that this money found its way to the Congress party and its friends. On October 9th the Hindu, a respected daily newspaper, offered new documentary evidence that the deal was corrupt.

The newspaper published parts of a previously secret report by Sweden’s National Bureau of Audit into what the bureau calls ‘the commissions’ paid by Bofors to win the contract. Bofors made transfers of 188m Swedish kronor ($26m in 1986) to coded accounts in Switzerland. When the Swedish central bank queried the transfers, Bofors disclosed that the principal beneficiary, a Panama-registered company called Svenska Inc. was ‘an Indian who has been an agent for Bofors for 10-15 years’.

The agent’s name is not given in the report, but Mr Win Chadda has openly represented Bofors in India since the mid-1970s. Documents obtained by the Hindu in 1988 strongly suggested that ‘Svenska’ was Mr Chadda. However, when the Indian government investigated him that year for tax evasion and foreign-exchange violations, it gave him a clean bill of health. Conspiracy theorists infer from this exoneration that Mr Chadda was the conduit through which the Bofors money reached its intended beneficiaries in the Congress party.

That aside, this week’s account contradicts assertions by Mr Gandhi to parliament in 1987 that negotiations for the Bofors gun had been meticulously handled, and that no middlemen had been involved. Mr Gandhi may have believed that then, but a brief version of the Swedish report was published later that year. He subsequently told a group of editors that Bofors had assured the Indian government the 188m kronor was a payment for ending an arrangement with a non-Indian agent. On two occasions later he repeated that, to the best of his knowledge, no Indian was involved.

An Indian parliamentary commission went even further. It reported that ‘the question of payments to any Indian or Indian company, whether resident in India or not, simply does not arise.’

Many Indians suspect that, behind its virtuous public façade, the government has been trying to prevent the recipients of the commissions from becoming known. Persistent inquiries from the Swedish public prosecutor asking whether any Indian had been charged in connection with the Bofors affair went unanswered. The prosecutor had made it clear that his information would be made available to the Indian government if it was needed in a criminal investigation. No such investigation has ever been started.

The opposition to Mr Gandhi, led by Mr V.P. Singh, once his finance minister, was naturally delighted by the Hindu’s story. When parliament met on October 11th, Mr Gandhi, known in his early days of office as the ‘Mr Clean’ of Indian politics, was taunted by opposition shouts of ‘Mr Dirty, resign!’

The financial troubles of Indian politics reach back much further than the Bofors case – to 1970, in fact, when Indira Gandhi banned business donations to parties but did not create any alternative to meet election expenses. Mr Singh has promised that if he comes to power he will set up a national fund that parties could draw on Would this end corruption in Indian politics? The voters will soon be asked for their view.

Coda

One caveat. We shouldn’t take, what had appeared in the Economist reports, as the Holy writ, for three reasons. First, Economist is still burdened by it’s peculiar British colonial bias, of viewing the non-white population with distorted glasses. Secondly, the unnamed local reporters (to earn their paychecks in pound sterling) also have a tendency to twist tales. Thirdly, Economist do NOT correct the errors subsequently, when more details become available with the passage of time. What I had presented at the beginning about the assassination of Amirthalingam ‘by LTTE’ is a good example. Future historians should corroborate the coverage presented in the Economist, with those of Time, Newsweek, Asiaweek and Far Eastern Economic Review, published between 1983 and 2000. Regrettably, due to digital trends that engulfed news coverage and dissemination in this century, Asiaweek and Far Eastern Economic Review are defunct now, while Time and Newsweek had lost their luster as print news weeklies. As such, I opt for the first drafts of contemporary history still available in the Economist, for its succinctness and continuity.

It should not be overlooked that Rajiv Gandhi was a man with pride, and he wouldn’t have forgotten the humiliation he received at Colombo (being beaten by a naval rating with the gun but, so publicly) on the day after he had signed the ill-fated Rajiv-Jayewardene agreement in July 1987. That’s why he stood his ground, in not withdrawing the IPKF army despite Premadasa’s saber-rattling. The IPKF was completely withdrawn from Sri Lanka, only after he had lost the November 1989 general election and the prime minister position.

Furthermore, something NOT mentioned in these 12 Economist news reports also deserve attention. RAW operatives also helped quite a number of JVP activists (who were hunted by the Premadasa government) to escape via India. Dayapala Thiranagama (the husband of Dr. Rajani Thiranagama) was one of them.