An Appreciation

by Sachi Sri Kantha, April 15, 2025

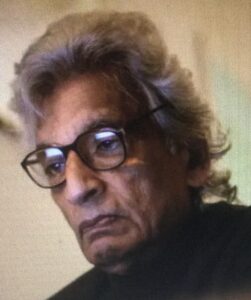

Prof Gananath Obeyesekere

The death of Prof. Gananath Obeyesekere on March 25th, at the age of 95 in Colombo saddened me. Though his physical frame has departed, what he has left behind in his published books and research papers in journals do remain, to offer guidance to various research themes relating to anthropology, Buddhism –Hinduism fluidity, ethnicity as well as ethnocide and Sri Lankan history. Prof. Obeyesekere’s academic affiliations with the University of California, San Diego, and Princeton University and 15 books published between 1967 and 2022 cemented his intellectual status as one of the foremost internationally renowned anthropologists of the 20th-21st centuries. Interestingly, his first degree from the University of Peradeniya in 1955 was in English literature.

A Brief Eulogy

On April 2nd, my brief eulogy to this gentleman-scholar was posted in the Tuppahi’s blog of Prof. Michael Roberts [https://thuppahis.com/2025/04/01/gananaths-manifold-reach-many-voices-in-vale/#comments] I wrote,

“I was saddened to hear the death of esteemed anthropologist Prof. Gananath Obeyesekere. Though I never met him in person, for me, he was a specialist teacher, via his published papers — on the Pattini cult, Kataragama and Mahavamsa episodes. Two of my favorite Obeyesekere’s papers were his interpretations of Mahavamsa chapters.

(1) The myth of the human sacrifice: History, story and debate in a Buddhist chronicle. Social Analysis: International Journal of Anthropology, Sept 1989; no 25: 78-93.

(2) The conscience of the parricide; a study in Buddhist history. Man, Jan 1989; 24(2) 236-254.

In these two papers, Obeyesekere lucidly established the case that King Kasyappa (elder born son of King Dhatusena) was partly Tamil, because his mother was of Tamil origin! King Mogallana, the latter born son of King Dhatusena, was born to a Sinhalese mother. This neatly explained the conflict described in the Mahavamsa. Here lies one reason why some Sinhala nationalists objected to Obeyesekere’s scholarship, which he himself had cast aside by self-deprecating humor.”

An Expanded Appreciation

Here, I’ll expand a little more. While other peers of Obeyesekere in USA, Sri Lanka and elsewhere may remember his scholarship differently, my focus will be on his angle of studying the past history of Sri Lanka (Ceylon/Serendip) without blinkered eyes and mind. In my view, Obeyesekere remains the most prominent Sinhalese scholar to track the origin and history of Sinhalese ethnics as ‘hybrid Tamils’ or ‘transformed Tamils’, (though he had refrained from openly indicating this unpleasant fact). Obeyesekere had prominently espoused this view in tracing the two millennia of island’s past history with evidence; beginning from King Gajabahu (regnal years AD 114-136), to parricide king Kasyappa (regnal years AD 473-491), followed by Polonaruwa period, and Nayakkar period (AD 1707-1815), British colonial period of 19th century and up to prime minister Sirima Ratwatte-Bandaranaike (1916-2000).

To support my point of view, I provide few excerpts culled from Prof. Obeyesekere’s research papers. Though he himself had NOT stated the obvious, in totality one can infer that the Sinhalese ethnicity was derived from South Indian Tamil (as well as Telugu and Kerala) tribes. For this particular reason, he fell foul to the rabble-rousing Sinhala nationalists.

In his 1978 study on the firewalkers of Kataragama, Prof. Obeyesekere had debunked the prevalent myth that Skanda was a Sinhala Buddhist god, linked to warrior king Dutugemunu as follows: “One well known mythic charter states that he [God Skanda] helped the great Sinhala king and hero Dutugemunu (161-137 BC) to defeat the Tamils, and that it was to commemorate this victory that Dutugemunu built the shrine at Kataragama in honor of the deity. Having no historicity whatsoever, this myth must be seen as an attempt to make Skanda not just a Sinhala Buddhist god but an anti-Tamil Hindu one to boot. The social backdrop of the myth is, of course, the disconcerting Tamil Hindu presence in Kataragama.” [J Asian Studies, May 1978; 37(3): 457-476]

Subsequently, in a 1991 essay on Buddhism and Conscience, Obeyesekere critiqued the activism of pro-Aryan apologist Anagarika Dharmapala, as follows:

“ He resurrected the myth of Dutugemunu, a famous king of the second century BC, who rescued the nation and Buddhism from the yoke of the Tamil rulers who had conquered the country. This myth has in our own times become the rallying cry for modern day nationalists, but it was Dharmapala who first employed it in this sense: ‘Enter into the realms of our king Dutugemunu in spirit and try to identify yourself with the thoughts of that great king who rescued Buddhism and our nationalism from oblivion.’” [Daedalus, 1991; 120(3): 219-239]

In another perceptive 1989 study on specific episodes presented in the Mahavamsa chronicle, Obeyesekere had noted the following:

“Mahavamsa I was not the first historical chronicle written in Sri Lanka. The Dipavamsa (‘Island Chronicle’) was written a hundred years earlier in somewhat inelegant Pali verse…It is ‘history’ in the narrow sense of a chronological narrative of kings and their activities. It virtually eliminates ‘story’. Thus, the Dipavamsa deals with the reign of Dutugemunu in the barest detail only, whereas in the Mahavamsa I the events in his life are incorporated into a narrative or story. Dutugemunu is, in fact, the main character in the chronicle, since it is he who gave the nation a specific Sinhala-Buddhist polity…’ [Social Analysis – Internat J Anthropol., Sep 1989; no. 25: 78-93]

But, to my knowledge, Obeyesekere had NOT expanded further, on what should have happened in the island, between the critical time frame that lapsed (100-150 years during 4th and first half of 6th century AD) between the compilations of Dipavamsa and Mahavamsa I. Probably, he had left it for junior researchers to fill in the blank. My postulation was, there could have been a large influx of Hindus converted Buddhists from northern and middle regions (currently Bihar, Orissa and northern Andhra Pradesh) of India to Ceylon, due to re-emergence of Hinduism in northern and mid regions of India. In my recent study on the origin of Kama Sutra treatise compiled by Vatsyayana in the 4th century AD, I had suggested a reason. It was compiled as a hedonistic life-enhancing Hindu response to rebut life-averse Buddhist doctrines. [Sexography of Vatsyayana, International Medical Journal, 2023; 30 333-334.]

King Kasyapa story

Furthermore, in his 1989 study on Mahavamsa episodes, Obeyesekere pried open a fact that lies hidden in the history books by other Sinhalese and non-Sinhalese authors. This relates to the antagonism of the two sons of King Dhatusena (regnal years AD 455 – 473)– elder son Kasyapa and younger son Mugalan. I quote Obeyesekere’s lines below:

“One of the most complete stories that I have in my possession is by Vaidya (physician) P. Kiribanda (84 years) of Kalundava near Sigiriya. Owing to its length, I cannot quote it here, except to mention that it deals with Dhatusena’s earlier years, his amours with a Tamil woman from whom he had a son, Kasyapa, the death of this lady and his marriage to a Sinhala woman whose son was Mugalan.”

In the Mahavamsa episodes, next to the exploits of King Dutugemunu (regnal years 161-137 BC) and his ancestor King Devanampiya Tissa (tentative regnal years 307-267 BC), the story of parricide by King Kasyapa (regnal years AD 473-491) was a spectacular event. This parricide episode was brought to screen in two movies. First, a Sinhala black and white movie in 1966 with the title ‘Sigiri Kasyapa’, with Gamini Fonseka starring in the title role, David Dharmakeerthi as king Dhatusena and Don Premarathna as Mugalan. Subsequently, another bi-lingual version directed by respected Lester James Peries was released in 1975 with the title ‘The God King’. Here, the lead role was played by British actor Allan Leigh Lawson; another British actor Geoffrey Russell played king Dhatusena role, and Sinhalese star Ravindra Randeniya was chosen to enact Mugalan role.

The Culavamsa –Mahavamsa chronicle records the fate of King Dhatusena in chapter 38 as follows: “the brutal (Senapathi) stripped the king naked, bound him with chains and fetters in a niche in the wall, with his face outwards and closed it up with clay.” A footnote is added by the translator: ‘According to my conception of the passage, the idea is that Dhatusena’s torture should be increased by his being a witness of the whole process of being immured.’

Why Kasyapa had to kill his father in such a horrendous manner of cementing him to the wall is somewhat neatly explained by Obeyesekere’s revelation that King Dhatusena’s first wife was a Tamil, and King Kasyapa was a hybrid Tamil. Lest many feel pity on the bad karma of Dhatusena, it should not be forgotten that he himself had killed (put to death) three of his predecessors – Khudda Parinda, Datthiya and Pitthiya, derisively tagged as ‘South Indian usurpers of the throne’. The modes of Dhatusena’s killing of these three are lost to history. But, one murder (a siblicide) committed by Dhatusena is recorded in the Culavamsa chronicle – He had burnt his own sister naked!, son of whom was given in marriage to his own daughter. This obscene act sealed Dhatusena’s fate. Son Kasyappa teamed with his cross-cousin Migara (his sister’s husband, who was snorting on the treatment met by his mother) to seal the King in the wall.

Other historians such as Rev.Walpola Rahula (1956), K.M. de Silva (1981), Nandadeva Wijesekera (1990), W.I. Siriweera (2002) and even Sir Emerson Tennent (1859) had ignored these untidy facts in their books! Noted years within parenthesis next to the name identify the published year of the book, for each mentioned historian I had checked. As the Culavamsa -Mahavamsa records in chapter 39, while ‘the wicked ruler called Kassapa’ [Kasyapa] held court in Sigiriya rock for 18 years, Mugalan (his younger sibling from Sinhalese mother) fled to South India (called Jambudipa) and returned with an army to claim his father’s throne. In the eventual battle, Kasyapa lost and committed suicide, for Mugalan to become the next ruler, for another 18 years. But, Culavamsa chronicle is silent on how Mugalan survived as a stranger for 18 years in a Tamil speaking territory (unless he also had some maternal links in Tamil Nadu), and assembled an army of Tamil speakers to return to the island to wage war against his elder brother! This is what the German translator of Mahavamsa chronicle, Wilhelm Geiger had pointedly noted in his introduction to Culavamsa – being the more recent part of the Mahavamsa (1928): “Not what is said but what is left unsaid is the besetting difficulty of Sinhalese history”. One is also puzzled by some sort of fiddling with recorded regnal years; Dhatusena ruled for 18 years; Kasyapa ruled for 18 years; and Mugalan also ruled for 18 years!

As an aside, I have to note this. Since I began to study the island history seriously 50 years ago, I was fascinated by this name Kasyapa, which had a distinct Tamil phonetical ring to it – Kasi+appan. Tamils carry similar names with ‘Kasi’ as the prefix. Examples include Kasilingam, Kasinathan, Kasipillai, Kasipathy and Kasichetty. Among these, the most prominent is Tamil cinema pioneer A. Kasilingam, who had directed quite a number of MGR and Sivaji Ganesan movies. Kasichetty is also a recognized name of a Sri Lankan Tamil scholar of 19th century. It was left to Prof Obeyesekere to solve the mystery behind this King Kasyapa name, that he was a hybrid-Tamil!

Abundance of Tamil blood among Sinhalese rulers

In another paper on Kataragama deities [Man, 1977; 12(3-4): 377-396], covering the period from fifteenth to early nineteenth century, Obeyesekere had inferred that quite a number of kings, considered nominally as ‘Sinhalese’ had either a parent and/or spouse(s) who were of South Indian origin. Thus the genealogy of the so-called ‘Sinhalese kings’ had abundant mixture of Tamil blood. Due to this fact, there had happened waves of Tamil-speaking non-Brahmin Pandaram caste and large number of low caste mendicants (termed aandis) immigrants who morphed into Sinhalese in subsequent centuries. And by 1707, Kandy kingship passed completely into the hands of the south Indian Nayakkars. To quote Obeyesekere,

“The popularity of Skanda [as the God] took a sharp upturn from the fifteenth to the early nineteenth century. I attribute this to several reasons. Firstly, an increased influx of south Indian immigrants, bringing with them some of their popular deities. One of the most important class of immigrants were the pandarams, non-Brahmin priests of the vellala caste in south India, today managers of Shaivite temples. Two waves of pantarams are recorded in the chronicles in the thirteenth and in the fifteenth centuries. They were given villages for their maintenance and absorbed into the Sinhala aristocracy. The title Bandara, used later for Kandyan nobility, Dewaraja says, came from the Tamil term pantaram. Another, but socially less significant class of immigrants, were the andi, low caste south Indian mendicant devotees of Siva, and particularly of Skanda. King Rajasinghe of Sitavaka (1581-93), the apostate king who espoused Hinduism not only encouraged Brahmins but settled a large number of andi in the Hevaheta area. To conclude, the presence of influential south Indian groups probably gave a fillip to the worship of Skanda, who was the foremost popular god of south India.

Secondly, some of the kings themselves gave their patronage to the cult. King Buvenaka Bahu VI (1470-1478), though himself a Buddhist, was the son of a south Indian nobleman. Many of the Kandyan kings married south Indian princesses, beginning with Rajasinghe II (1635-87). Soon south Indian Nayakkars of Madura became an influential aristocracy in the Kandyan court….”

Also, in a paper published in 2015, Obeyesekere even pointed out the following fact:

“… some of the most distinguished Sri Lankans such as the Ratvattes to which former Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranayaka and her daughter, former President Chandrika Bandaranayaka belong, originally came from this line of Brahmin settlers.” [Society and Culture in South Asia, 2015; 1(1) 1-32]

Fire walking in Kathirgamam (Kataragama)

In his interesting book ‘Medusa’s Hair: An Essay on Personal Symbols and Religious Experience’ (1981, 217 pages), Obeyesekere had analyzed how the spectacular fire-walking rituals of Hindus at the famous Murugan temple of Kathirgamam had been hijacked by Sinhala Buddhist ‘samis’ since early 1950s due to ‘emerging political dominance of Sinhala Buddhists and with strong Sinhala resentment against Tamils, mostly based on language nationalism’. Obeyesekere had identified the chief culprits as an upstart Vijeratna Sami in 1942 followed by Mutukuda Sami in 1949, who took on the role of ‘chief fire walker’. Obeyesekere also pointed out, (1) ‘No more Hindus have been nominated to the post of chief fire walker, but note that the Sinhala Buddhists have taken over the term sami, lord, until then reserved exclusively for Hindu priests. (2) ‘Even after Muthukuda Sami took control of the fire walk from the Tamils, the Murugan kavadi was carried by a Hindu Tamil, Kandiah Sami, across the fire pit. When this sami died in about 1957, Vijeratna Sami took over this ritual and changed the name Murugan kavadi into murutan kavadi. Vijeratna said that the real meaning of murutan is multan, the Sinhala Buddhist term for a food offering to the gods…”

I’m not sure about Prof. Obeyesekere’s fluency in Tamil language. My observation is, Vijeratna Samy might have twisted the word for God Murugan to murutan. But, he couldn’t replace the Tamil word ‘kavadi’, thus still kept it as ‘murutan kavadi’. The combined Tamil word ‘kavadi’ is derived from two words – verb kavu (carry) plus the noun tadi (stick). It is a form of special penance ritual to God Murugan, to carry an arch stick, in the shoulder and neck and twisting/shaking with hands, while walking or dancing.

As one would predict, Obeyesekere’s inferences on the influence of Hindu culture among Sinhala Buddhists were NOT to the taste of contemporary Sinhalese nationalists. Thus, his research had been attacked openly. One such critic was an engineer- turned anthropologist wannabe Susantha Goonetilake. His criticism of Obeyesekere’s research was entitled ‘White sahibs, brown sahibs: Tracking Dharmapala’ [Journal of Royal Asiatic Society of Sri Lanka, 2008; new series 5: 53-136]. A sample paragraph from Goonetilake’s criticism on Obeyesekere’s studies reads as follows:

“His statements show a basic ignorance of the intellectual history and sociology of knowledge. Abstract thought is not limited as he claims to the presumed Axial Age or civilizations, but extends to the simplest of societies. This is one of the crowning findings of anthropology as illustrated for example, in classificatory systems in ethno botany. For an anthropologist, he seems to be blissfully unaware of such undergraduate level elementary facts.”

For those who are interested in hearing Prof. Obeyesekere’s voice and thoughts, I suggest watching his 2003 interview with Harry Kreisler – Conversations with History, 2003 Mar 19. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PEeaUGDw1PY

A final word: I do recognize that many Sinhalese academics and journalists may find it difficult to agree with what I (as an amateur anthropologist and historian) have presented about Prof Obeyesekere’s scholarship. Those who are keen to disprove my thoughts, are invited to dip into his original writings listed below, to satisfy their curiosity.

Chronological list of Research Papers

Below, I have assembled a list of Obeyesekere’s research papers chronologically, from diverse sources. I cannot vouch for its completeness. Nevertheless, I have no doubt that these papers will provide much inspiration to younger generation of anthropologists, all over the world.

Obeyesekere G. The pataha ritual genesis and function. Spolia Zeylanica, Dec 1965; 30(2) 279-296.

Obeyesekere G. The Sinhalese folk poem. Ceylon University Magazine, Sep 1954; pp. 20-31.

Obeyesekere G. The Narammala road. Ceylon University Magazine, Nov 1954; pp. 8-17.

Obeyesekere G. Magic and religion in Ceylon. Inst. of International Education – News Bulletin, Apr 1957; 32 35-38.

Obeyesekere G. The structure of a Sinhalese ritual. Ceyl J Historical Social Studies Jul-Dec 1958; 1(2) 192-202.

Obeyesekere G. The Great tradition and the Little in the perspective of Sinhalese Buddhism. J Asian Studies, Feb 1963; 22(2): 139-153.

Obeyesekere G. Pregnancy cravings (dola-duka) in relation to social structure and personality in a Sinhalese village. Amer. Anthropol., April 1963; 65(2) 323-342.

Obeyesekere G. The ritual drama of the sanni demons: collective representations of disease in Ceylon. Comp Studies in Society and History, April 1969; 11(2) 174-216.

Obeyesekere G. The cultural background of Sinhalese medicine. J Indian Anthropol Society, 1969; 4 117-139.

Obeyesekere G. Gajabahu and the Gajabahu synchronism: an inquiry into the relationship between myth and history. Ceyl J Humanities, Jan 1970; 1(1) 25-56.

Obeyesekere G. Religious symbolism and political change in Ceylon. Modern Ceylon Studies, Jan 1970; 1(1): 43-63.

Obeyesekere G. The idiom of demonic possession – a case study. Social Sci, Medicine (London), 1970; 4 97-111.

Obeyesekere G. Ayurveda and mental illness. Comp Stud Social History, 1970; 12: 292-296.

Obeyesekere G. The Goddess Pattini and the Lord Buddha: notes on the myth of the birth of the deity. Social Compass (Brussels), 1973; 20(2): 217-229.

Obeyesekere G. Some comments on the social backgrounds of the April 1971 insurgency in Sri Lanka (Ceylon). J Asian Studies (Ann Arbor, MI), May 1974; 33(3) 367-384,

Obeyesekere G. Sorcery, premeditated murder and the canalization of aggression in Sri Lanka. Ethnology, Jan 1975; 14(1): 1-23.

Obeyesekere R and Obeyesekere G. Comic ritual dramas in Sri Lanka. The Drama Review, Mar 1976; 20(1) 5-19.

Obeyesekere G. More pills or fewer? Hemisphere, Mar 1977; 21(3) 20-22.

Obeyesekere G. Social change and the deities: The rise of the Kataragama cult in modern Sri Lanka. Man, new series 1977: 12(3-4): 377-396.

Obeyesekere G. The theory and practice of psychological medicine in the ayurvedic tradition. Culture Medicine & Psychiatry (Dordrecht), 1977; 1: 155-181.

Obeyesekere G. The firewalkers of Kataragama: the rise of Bhakti religiosity in Buddhist Sri Lanka. J Asian Studies, May 1978; 37(3): 457-476.

Obeyesekere G. Re-reflections on Pattini and Medusa. Contributions to Indian Sociol., 1987; 21(1): 99-109.

Obeyesekere G. The conscience of the parricide: a study in Buddhist history. Man new series, June 1989; 24(2): 236-254.

Obeyesekere G. The myth of the human sacrifice: History, story and debate in a Buddhist chronicle. Social Analysis – Internat J Anthropol., Sep 1989; no. 25: 78-93.

Obeyesekere G. Buddhism and conscience: an exploratory essay. Daedalus, 1991; 120(3): 219-239.

Obeyesekere G. ‘British cannibals’: contemplation of an event in the death and resurrection of James Cook, explorer. Critical Inquiry, 1992; 18 630-654.

Obeyesekere G. The coming of Brahmin migrants: The sudra fate of an Indian elite in Sri Lanka. Soc Culture in South Asia, 2015; 1(1) 1-32.

****

Kashyap is a Brahmin gotra, those of Rishi Kashyap lineage. Not Kasiappan. And even Kāśī (काशी) isn’t Tamil, but Sanskrit, it’s a reference to Varanasi.

Just today, I noted this comment from Rana. It is an interesting thought. Why, one should link the Tamil word ‘Kasi’ to Rishi Kashyap lineage? Homonyms (intra-lingual and inter-lingual) leads to debate, whether which language borrowed from which language?

I suggest Rana to check a Tamil dictionary, to find various meanings of words that derive from ‘Kasi’. Not all, can be traced to a Rishi named Kashyap and a Brahmin gotra. Here are few, which I picked up from Dictionary – Tamil and English, by V. Visvanatha Pillai (1951).

Kasi – a city, Benares.

Kasi kal – loadstone

Kasi caram – a mineral salt

Kasi thumbai – a flowering shrub

Kasiram – a circle

Kasini – the Earth

I can expand further on this point. For example, ‘Nathan’ is a Hebrew word, and Jews use it in their names. Tamils also have names ending in ‘Nathan’ suffix’, or beginning with ‘Nathan’ prefix. Should that mean, Tamil language borrowed the ‘Nathan’ root from Hebrew?

For curiosity and comparison to solve this issue, whether the word ‘Kasyapa’ was borrowed from Sanskrit into Tamil, I also checked the Monier Williams’s A Sanskrit-English Dictionary, published in 1872. Monier Williams was the Professor of Sanskrit, at the University of Oxford.

In page 215, of this book, he had recorded the variant uses for the word ‘Kasyapa’. It is as follows

“having black teeth; a tortoise; a sort of fish; a kind of deer; a class of divine beings similar to or equal to Prajapati; a mythical Rishi.

N(oun): of an old sage, conversant with the Mantras, author of several hymns of the Rig-veda; he is also regarded as one of the seven sages, and in some legends as father of Vivasvat and of Vishnu.

He is supposed by some to be a personification of the race who resided in Caucasus, the Caspian, Kashmir, & c.); the author of Dharmasastra.

An epithet of Garuda, the bird of Vishnu.”

Well, thus we can deduce that the meaning of ‘Kasi’ in Sanskrit and Tamil varies. Monier Williams DO NOT mention anything about Varanasi city. He also do not mention anything about Kasiram (a circle) and Kasini (the Earth). Semantically, the meaning of the word ‘Kasi’ in Tamil and Sanskrit are in variance.