by Julie McCarthy, National Public Radio, Washington, DC, August 19, 2015

The Jaffna Public Library, destroyed in 1981 and rebuilt twice since, once sat in a no man’s land between warring forces. It’s been fully restored and become a haven for readers young and old.

Rising two stories and capped by three domes, the Jaffna Public Library looks a bit like a stately wedding cake. Gleaming white under the Sri Lanka sun, the building’s classical lines and beautiful proportions make it one of the architectural standouts of the South Asia region.

That it survived at all is a testament to resilience. The fact that it was restored to such pristine condition, including its lush gardens, and modernized (it now offers Wi-Fi) makes it all the more remarkable.

The library’s renovation is as exquisite as its history is turbulent. The building sits in the heart of the provincial capital that was wracked not so long ago by battles and bullets.

A three-decade civil war pitted Sri Lankan forces against rebels fighting a brutal campaign for a separate homeland for ethnic Tamils. The rebels, known as Tamil Tigers, were crushed in 2009, in the closing months of the fighting.

Incinerated History

At the library’s front entrance, a statue of Saraswati, the Hindu goddess of learning, beckons visitors inside.

Past the lobby, on the left, oversized teak windows frame an airy reading room that pulls in an Indian Ocean breeze and patrons who pack the place on Sunday afternoons.

Perhaps it’s not unexpected in a country with a 92 percent literacy rate.

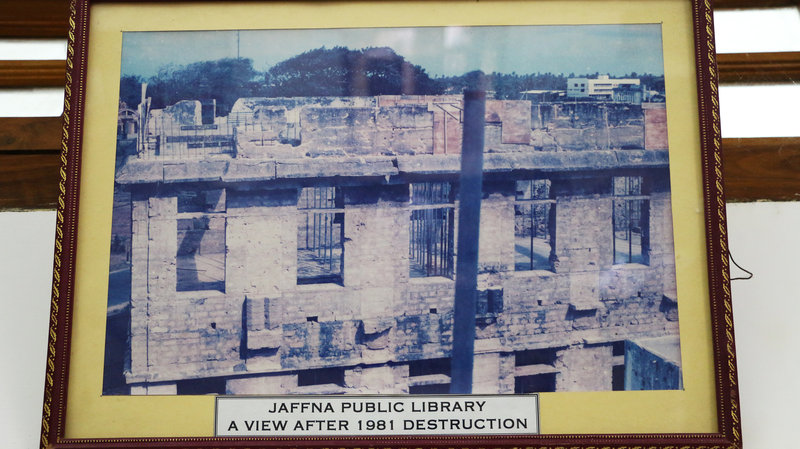

This framed picture depicts the library in 1981, after it was destroyed in a fire that Sri Lankan Tamils suspect was set by government police.

Looking at the library today, you wouldn’t know that this landmark was gutted in a mysterious fire in 1981.

“It was completely destroyed. And at that time, nobody knows who was inside the library,” says S. Thanabaalasinham, the retired chief librarian. He says six rooms full of material — 97,000 volumes — were turned to ash.

“The history of the Tamil people” was incinerated, he says, including “valuable books of Hindu philosophers, irreplaceable ancient texts, scrolls written on palm leaves,” as they had been for centuries. Previously, these works had been housed in Hindu temples, which in some ways served as the precursor to libraries on the island.

S. Thanabaalasinham, the library’s retired chief librarian, says 97,000 volumes were lost when the library was destroyed in 1981.

Sri Lanka’s mainly Hindu Tamil minority suspects that police from the mostly Buddhist Sinhalese majority set the 1981 library fire. It foreshadowed the bigger conflict to come between the government and the Tamil Tigers.

With donations from well-wishers around the world, the library was fully renovated in 1984.

But within a year, Jaffna was engulfed in the civil war. With the newly refurbished library at ground zero, shells careened over the roof. Thanabaalasinham says it wasn’t long before the building was assaulted head-on, targeted because Tamil insurgents took up residence “in what was left of the lending room.”

“It became the place where the rebels billeted themselves,” he says.

From No Man’s Land To New Beginning

They operated just yards from where the government forces were stationed in an old Dutch fort that sits along the coast.

“The un-man zone,” the former librarian calls it.

It would remain a no man’s land through much of the 1990s, when fighting intensified and civilian casualties in the war climbed into the thousands.

In 1990, Thanabaalasinham, who had studied at the Jaffna library as a young man, returned as its librarian. With the main building shuttered, he struggled to fill the gap by setting up five smaller branches around the city.

Burned, rebuilt and then bombed into ruins, the main library improbably rose again a second time. Beginning in 2000, blackened floors were hauled away and gutted rooms repaired in a $1 million face-lift, financed by the central government and international donors.

When political rivals could not decide on the size of the reinauguration, Thanabaalasinham took matters into his own hands and personally threw open the doors in February 2004.

Library patrons fill the main reading room on Sundays.

“The students came every day to the gate and said, ‘We need to get in; we have exams coming up and we need to study,’ ” recalls the 67-year old public servant.

According to the National Library of Sri Lanka, there are some 1,135 public libraries for the country’s 20 million citizens. A small municipality can house its modest collection in the town hall. The country’s only two major libraries are the Colombo Public Library, in the capital, and the library in Jaffna.

Today, Jaffna’s shelves groan under the weight of books on computer science and mathematics, along with best-sellers from Peter Wright’sSpycatcher to Bill Bryson’s Made in America.

The library once at the heart of so much turmoil teems today with the young and the old. Fifteen and wide-eyed, Shareeq Ahmed marvels at the historical collection. “I got to see what happened on the day I was born,” he says. “I’ve never seen a library like this.”

Shareeq is too young to remember much of the war years. But for another patron, 75-year-old Rajenthiran Selvanayagam, spending time at the library is a peaceful contrast to that era. He lost his wife to the war. His son went mad.

Selvanayagam visits the library three times a week. “Having a book in my hand,” he says, “is more than meditation to me.”