by Tamil Guardian, London, July 26, 2020

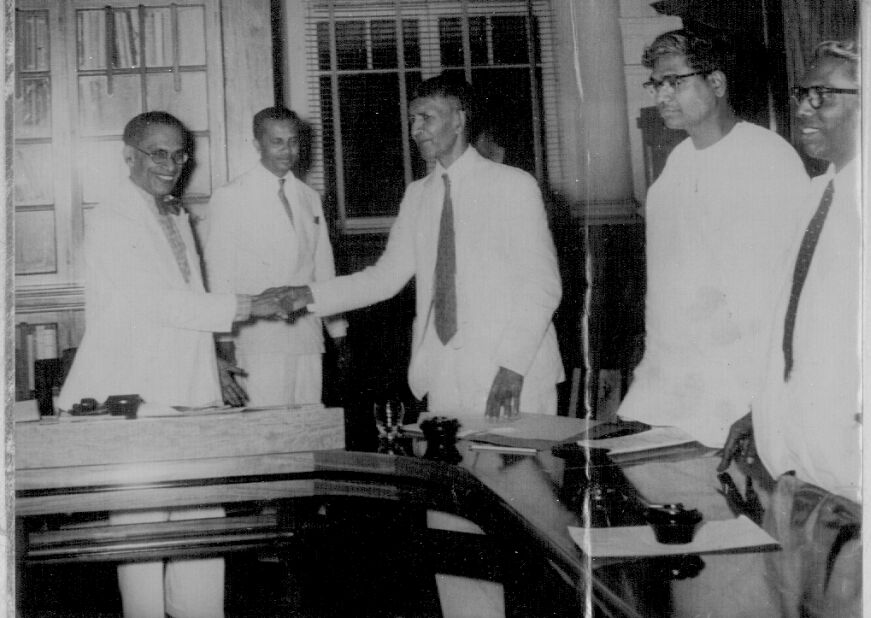

Bandaranaike and Chelvanayakam in 1957.

On 26th July 1957, Sri Lankan Prime Minister SWRD Bandaranaike and the leader of the Federal Party SJV Chelvanayakam signed a deal, that contained provisions for the recognition of Tamil as the language of administration for the Northern and Eastern provinces, which came to be known as the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayakam Pact.

This pact was the result of years of peaceful agitations by Tamil leaders in response to a series of Sinhala nationalist policies that the newly elected Sri Lankan government had enacted.

However, hawkish Sinhalese-Buddhist nationalists railed against the modicum of concessions given to the Tamil people leading ultimately to the unilateral abrogation of the agreement. This was one of the earliest instances of failed negotiations and broken agreements that would eventually seal Tamil hopes of achieving a settlement through Sri Lanka’s political processes.

Origins

The 1956 elections gave a landslide majority to the coalition Mahajana Eksath Peramuna. Led by SWRD Bandaranaike’s Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP), the coalition ran a campaign of ensuring the official language of the island would be ‘Sinhala Only’.

Under British colonial rule, English had been recognised as the national language despite the fact that only 10% of the population spoke it fluently. Though Sinhalese and the Tamil elites were in agreement that Sinhala and Tamil should replace the tongue of the British colonists as official languages, Sinhala nationalist movements were growing and began to clamour for using Sinhala alone as the national language.

Bandaranaike, a Sinhala nationalist who had earlier formed the nationalist Sinhala Maha Sabha party, was acutely aware of the political capital to be gained from a ‘Sinhala Only’ policy.

He remarked to a journalist, “I have never found anything to excite the people in quite the way this language issue does”.

As soon as his party came to power, he passed the Sinhala Only Act of 1956 which enshrined Sinhala as the sole national language of the country, relegating Tamil to a position inferior to that of Sinhala.

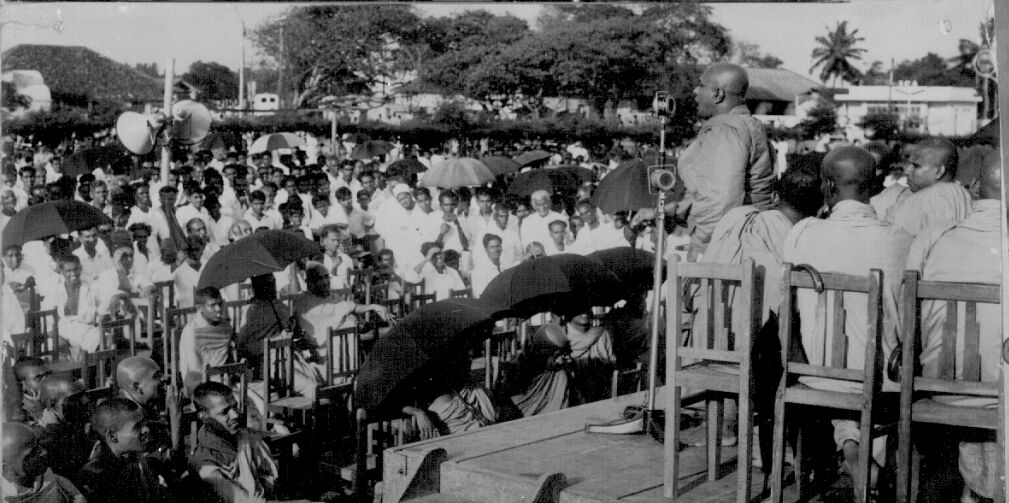

Chelvanayakam leads a protest against the Sinhala Only Act of 1956.

Chelvanayakam leads a protest against the Sinhala Only Act of 1956.

When the Tamils expressed their opposition to this flagrantly discriminatory policy by organising a peaceful movement of protest under the leadership of Chelvanayakam (leader of Ilankai Tamil Arasu Katchi aka Federal Party), the Sinhalese disturbed these movements.

Tamil politicians who had peacefully protested the bill at Galle Face Green, opposite to Sri Lanka’s Parliament, were attacked by Sinhala mobs and violent pogroms of Tamils ensued.

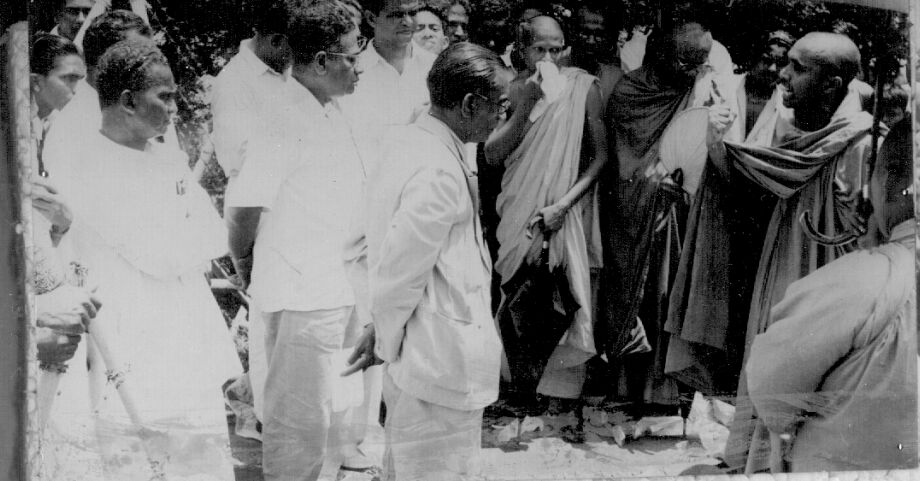

Attacks on Tamil protestors.

Attacks on Tamil protestors.

Tamil opposition

Despite the murder of hundreds of Tamils across the island by Sinhala mobs, Tamil politicians continued their opposition to the Sinhala Only policy.

The Federal Party convened in Trincomalee in mid-August 1956 to deliberate on its future course of action and came up with the following four demands;

1. The establishment of an autonomous Tamil state or states on a linguistic basis within a Federal Union of Ceylon.

2. The restoration of the Tamil language to its rightful place, enjoying absolute parity of status with Sinhala as an official language of this country.

3. The restoration of the citizenship and franchise rights to the Tamil workers in the plantation districts by repeal of the present citizenship laws.

4. The immediate cessation of all policies of colonising the traditionally Tamil-speaking areas with Sinhalese people.

The Federal Party decided to give the government one year’s time to deliver these demands or resort to “direct action by non-violent means” if these were not met.

In the meantime, the state ramped up ethnic tensions with the introduction of the use of the word ‘Sri’ in-vehicle number plates.

Tamils took umbrage at this move as they saw it as an instrument of Sinhala-imposition. They tarbrushed number plates that bore the word ‘Sri’ on them as part of a growing peaceful protest or satyagraha movement across the North-East. The Sinhalese responded by vandalising Tamil names in street signs and name boards.

As violence on the island began to rise, Bandaranaike was eventually forced into negotiations with the Federal Party delegates.

The Pact

After months of negotiation, Bandaranaike and Chelvanayakam agreed upon a settlement that neither satisfied Tamil demands nor contained boiling Sinhalese nationalism.

The Sri Lankan Prime Minister refused to accept the Tamil demand that their language be given equal status with Sinhala. Instead, Tamil was recognised as the ‘language of the national minority.’ It meant that Tamil could be used for administrative purposes in the North-East but would not be given parity with Sinhala. In another provision, regional councils were created that fell far short of regional autonomy. The Federal Party demanded that the Northern and Eastern provinces be merged into one unit. Instead, Bandaranaike made the North and East separate regional councils and made room for the division of the Eastern province into two or more units. Furthermore, on the question of citizenship to the Tamils working in plantations, an ambiguous provision was made that ‘the problem could receive early consideration’.

Read the full text of the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayakam pact here.

This highly toned-down list of concessions to the Tamils that hardly constituted regional autonomy, was disappointing to many Tamils, who had hoped for more in the negotiations.

“Chelvanayakam was not wholly pleased with the agreement, as was apparent when he returned home from the signing ceremony,” wrote A Jeyaratnam Wilson on the pact. “He had been worried by the protracted negotiations. The failure to obtain a single merged Tamil-speaking North-East Province left him dismayed; he said that narrow district parochialism could emerge in the absence of all-embracing Tamil region.”

However, this pact provoked yet more extreme Sinhalese nationalism.

What followed?

Sinhala Buddhist monks protest.

This modest recognition of Tamils and their language was politicised by the United National Party in a campaign of stoking sectarian animus against the Tamils spearheaded by further Sri Lankan president JR Jayewardene. Playing the ‘Sinhala card’ that paid huge dividends to Bandaranaike in the previous elections, Jayewardene continued to whip up a communal frenzy and touted himself as the true representative of the Sinhalese.

In the months after the pact was signed Bandaranaike was repeatedly forced to defend the agreement, telling an SLFP convention,

“In thinking over this problem I had in mind the fact that I am not merely a Prime Minister but a Buddhist Prime Minister. And my Buddhism is not of the “label” variety. I embraced Buddhism because I was intellectually convinced of its worth. At this juncture I said to myself: “Buddhism means so much to me, let me be dictated to only by the tenets of my faith, in these discussions. I am happy to say a solution was immediately forthcoming.”

The pact though had drawn the ire of the Sinhalese.

Jayewardene went on a march from Colombo to Kandy gathering support for his opposition to the B-C Pact, as he pledged to pray at the Buddhist Temple of the Tooth against the agreement. Buddhist monks jumped on the bandwagon and organised protest movements calling for the abrogation of the Pact.

Faced with immense pressure from the Sinhalese population, Bandaranaike eventually caved in and unilaterally rescinded the pact on April 9, 1958, symbolically tearing up a copy of it.

Bandaranaide & the bhikkus

Below is an excerpt from Emergency’58, The Story of the Ceylon Race Riots byTarzie Vittachi describing the events of the day.

“On the morning of April 9, a police message reached Mr Bandaranaike warning him that about 200 bhikkus or monks and 300 others were setting out on a visitation to the Prime Minister’s residence in Rosmead Place to demand the abrogation of the Pact. They would arrive at 9 a.m.”

“The Prime Minister left the house early that morning to attend to some very important work in his office. The bhikkus came, the crowds gathered, the gates of the Bandaranaike Walawwa were closed against them and armed police were hurriedly summoned to throw a barbed-wire cordon to keep the uninvited guests out. The bhikkus decided to bivouac on the street. Pedlars, cool-drink carts, betel sellers and even bangle merchants pitched their stalls hard by. Dhana was brought to the bhikkus at the appointed hour for food.”

“In the meantime, the Prime Minister was fighting off the opposition to the Pact among his own party colleagues with desperate fury.”

“At 4.15 p.m. the B-C Pact was torn into pathetic shreds by its principal author who now claimed that its implementation had been rendered impossible by the activities of the Federalists.”

“Yesterday, was the saddest day in the history of Ceylon’s racial relations,” reacted S Thondaman, the leader of Ceylon Workers Congress. “A solemn pact, worked out between the leadership of the country’s two main communities has been torn up because of the pressure of a group extremists. I am worried whether Tamils in the future will have trust in the Sinhala leadership.”

“The drama on the prime minister’s lawn, therefore, marked the victory of Bandaranaike’s enemies,” wrote V Navaratnam, an ITAK parliamentarian who had taken part in the negotiations. “They forced him to treat the B-C Pact like Adolf Hitler treated his solemn undertaking which he gave to Neville Chamberlain at Munich. To them the B-C Pact was as much a piece of paper as was the Munich paper to Hitler.”

The 1958 anti-Tamil pogrom

Photograph: A Sinhalese mob beats a Tamil passenger after pulling him out of his car. 1958. (Courtesy Victor Ivan)

The Federal Party decided to conduct a large-scale campaign of peaceful demonstration against the abrogation of the pact. However, Sinhalese mobs rampaged through the streets and killed, maimed and raped the Tamils in large numbers in what would become the infamous anti-Tamil pogrom of 1958.

Incidents were recorded when the state security apparatus including the police and the army did not lift a finger to rein in the fanatical and murderous mobs. Several Tamils were killed when a train was attacked which contained Tamils who were headed to Vavuniya to attend a Federal Party convention.

Estimates range from between 300 and 1,500 Tamils murdered in the days of violence which resulted in many more injured and the arson, looting and destruction of Tamil homes and businesses.

Bandaranaike accused “Federalists and other forces” of attempting” to overthrow the Central Government to set up a separate administration in the North and East” with several Tamil leaders arrested and imprisoned.

“I have thwarted that,” he reportedly declared. “Their attempts have been quelled. My military forces are now in the north and in the east. There is military rule in these two provinces, each with a military governor. Yes, I say they are military governors. With my army, I will see that there is no repeated attempt to set up a different administration in those provinces.”

In August 1958, even as some Tamil politicians languished in prison, the Tamil Language (Special Provisions) Act, 1958 was passed which provided for Tamil to be used as a medium of instruction in the North and East and for other subsidiary purposes.

On September 25, 1959, Bandaranaike was shot dead by, Talduwe Somarama, a Sinhala Buddhist monk who had joined a tide of nationalists becoming increasingly frustrated with the Sri Lankan government. Somarama was executed three years later.