Front Note by Sachi:

I provide this essay of little over 1,600 words by John Colmey which appeared in the In These Times (Chicago) fortnightly, 25 years ago. The individuals quoted in this essay were, Ranjan Wijeratne (then No. 2 honcho in President Premadasa’s cabinet), Gen. Cyril Ranatunge (then, Secretary to the Ministry of Defense), Sri Lankan civil service official Neville Jayaweera, Dr. Osmund Jayaratne and a few un-identified commoners from the South. It provides a description of the island, after the defeat of JVP’s 2nd rebellion, which spanned from 1987 to 1989. Two box stories which accompanied this feature are scanned and provided nearby.

Though this essay deals with the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) of 1989, then led by Rohana Wijeweera, the paths taken by some co-travelers carrying JVP’s thoughts in their minds who later flourished as ‘Sinhalese opinion-makers with a pronounced anti-Tamil bias’ have been left untouched by John Colmey. In the words of a representative of this tribe, Dr. Dayan Jayatilleka, “I belonged to the Vikalpa Kandayama, as did Dayapala Tiranagama, Pulsara Liyanage, Ram Manikkalingam, Qadri Ismail and Tisaranee Gunasekara among others, while Nirmal Ranjith Devasiri and CA Chandraprema were among those closely affiliated with the VK through the Independent Students Union (ISU).”[Fascism, sovereignty and the truth about the Tamil struggle, Jan.26, 2012; www.colombotelegraph.com/index.php/fascism-sovereignty-and-the-truth-about-the-tamil-struggle/]

As to the tenuous links between Dayan Jayatilleka and Dayapala Thiranagama, I reproduce a section of what I wrote in September 18, 2010, under the title, ‘Who killed Rajani Thiranagama?’ How convincing is the grape vine news? [http://new.sangam.org/2010/09/Who_Killed_Rajani.php?uid=4071] seems relevant here:

“Rajani’s husband Dayapala Thiranagama, in rebutting the views of raucous polemicist Dayan Jayatilleke posted the following comments to the transCurrents website of D.B.S. Jeyaraj, on October 4, 2009. I quote:

“At the time Dayan had joined the UNP government and was working for President Premadasa. I recall just before I left for London [in] December 1989, Dayan was of the view that Rajani was killed by the EPRLF and that he had had access to the information not available to us. Dayan wanted me to make a statement regarding this information. At the time the Premadasa government had an understanding with the Tamil Tigers against the IPKF and their proxy the EPRLF. That was the crux of the matter.”

Wow! What a revelation that Dayapala Thiranagama had divulged, after 20 years and placed Dayan Jayatilleka in a spot. This confession by Rajani’s husband fills in a few blank spots. He “left for London in December 1989”, one month after the execution of JVP leader Rohana Wijeweera and his coterie by the SL army. He doesn’t tell the details about how he was able to leave the island and who helped him, if he was living an underground life. Many Sri Lankans know that among the top-ranking JVPers of that time, only Somawansa Amarasinghe was able to escape execution by the SL army, courtesy RAW operatives.

In the same website, Dayan Jayatilleka, then rebutted Dayapala Thiranagama, as follows:

“Within days of her murder I had made a beeline to Sri Lankan Military Intelligence HQ at Flower Road and requested information. My interlocutor, who may have been Gen (at the time Brig or Col.) Chula Seneviratne, now retired, told me that according to reports they had at that moment, which were hazy due to the fog of low intensity war with multiple players, it was an EPRLF hit because Rajani’s polemical guns at the time had been trained on the IPKF. It is this that I shared in good faith with Dayapala.” [posted in transCurrents website, Oct.10, 2009.]

In this rebuttal, Dayan Jayatilleka had stated that, at that time he has yet to join the UNP. So, what was his party position then? – still belonging to the Vikalpa Kandayama or allied to Sri Lanka Mahajana Party (of Vijaya Kumaratunga and his wife Chandrika). Note that, he served as a cabinet minister in the North-East provincial council, headed by Varadharaja Perumal, from December 1988 to June 1989. Check his line, “My interlocutor, who may have been Gen Chula Seneviratne…” Jayatilleka was not sure, who provided the information in Sept. 1989 that “it was an EPRLF hit”. Why should an army officer who belongs to the Intelligence section provide complete information to a guy who is not a ‘big wig’ in the then ruling party hierarchy? Again, Jayatilleka states, “It is this that I shared in good faith with Dayapala.” That also indicates that, while Dayapala was living ‘underground’ hiding from the SL army militia, Jayatilleka was ‘keeping in touch’ with Rajani’s husband.

To wiggle out from the spot into Dayapala Thiranagama had fixed him, Dayan Jayatilleka in an escape gambit, then cited the inference of anti-LTTE scribe D.B.S. Jeyaraj. Living in Canada, for the past 20 years, Jeyaraj caters to the community of non-Tamils in Sri Lanka and elsewhere who cannot comprehend Tamil. But, the opportunistic swinging of Jeyaraj on Eelam Tamil issues is usually well understood by Tamils who can read, write and speak Tamil. Here is a case of intelligence of Jeyaraj (living in Canada) pitted against the Sri Lankan army’s military intelligence, having headquarters in Colombo, but tentacles all over the island, including Jaffna. Common sense indicates that Jeyaraj’s intelligence cannot be superior to that of Sri Lankan army’s military intelligence; but Jayatilleka’s intelligence, for simple convenience of scoring a brownie point, anoints Jeyaraj as a super sleuth! I can provide a list of Jeyaraj’s hoisted balloons that flopped.”

It should also be stressed that in Sri Lankan context, ‘Pol Potism’ was first used to JVP and its leadership in 1989. Only after the death of Rohana Wjeweera, the above mentioned Sinhalese ‘opinion makers’ to extricate themselves from JVP’s shades, began to tar LTTE and Prabakaran as ‘Pol Potists’, with the active collusion of Narashiman Ram of the Hindu group. For reference, will you care to check the current Wikipedia entry on Dayan Jayatilleka [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dayan_Jayatilleka; accessed Nov. 17, 2015]? Nothing is included there, about his activity as a radical member of pseudo-JVP, during the 1980s!

Sri Lanka: The Eye of the Storm

by John Colmey [In These Times, Chicago, May 23- June 5, 1990]

Colombo, Sri Lanka: Like the passing of a tropical storm, the reign of terror that ruled over southern Sri Lanka throughout 1989 is now almost over. Peace is back as farmers return to their rice fields, students to their classes, government workers to their jobs.

‘We are now riding a beautiful crest,’ said Nival Jayaweera, [note by Sachi: I guess, there is an error here. The correct identity of the official quoted here is Neville Jayaweera, and not Nival Jayaweera.] the former head of the Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation and now with the Norway-based Peace Research Institute. ‘Normalcy is returning, and people are happy.’

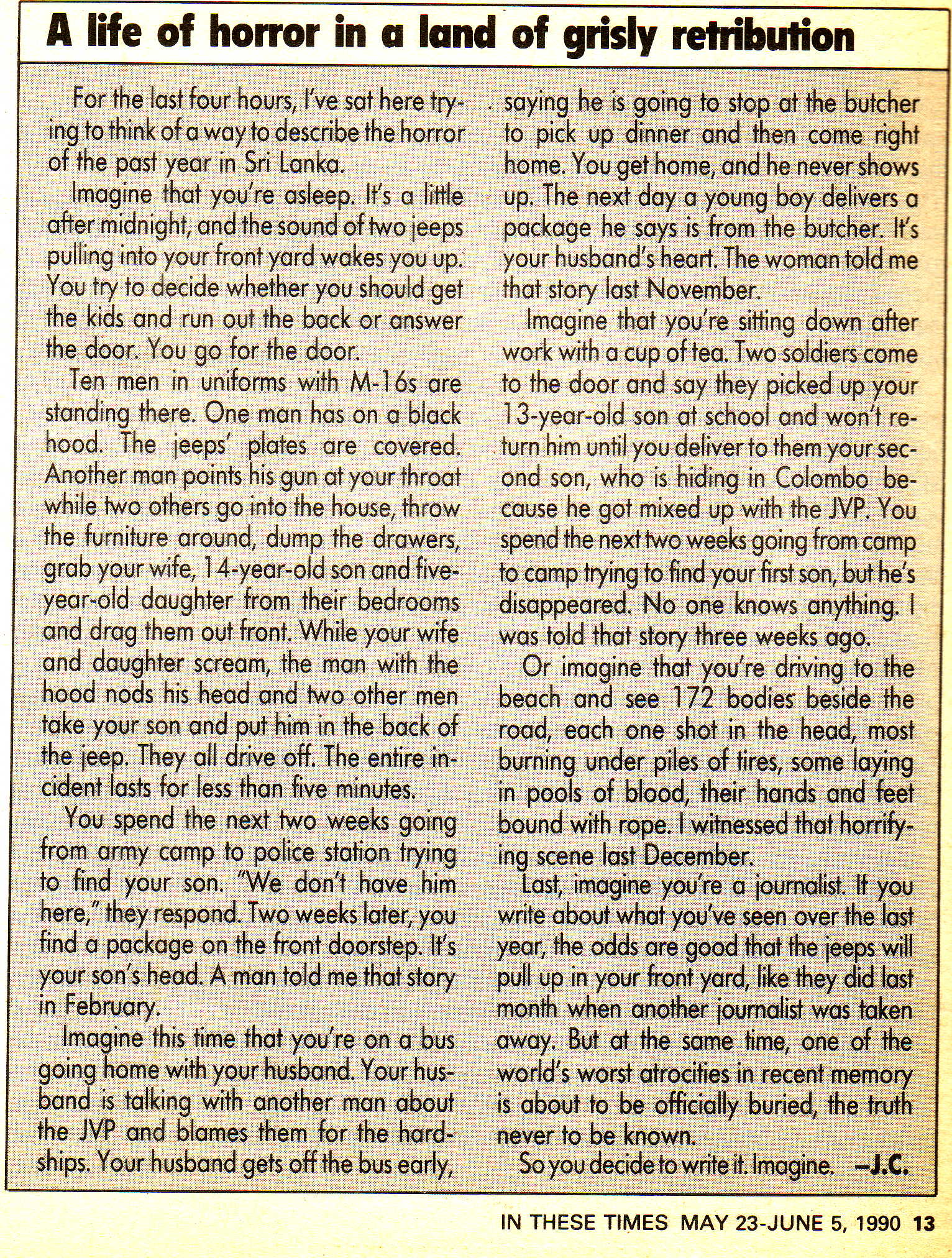

But it will take more than the upcoming monsoons to wash away the memories of the past 15 months, when a massive uprising by the nation’s youth under the Marxist banner of the militant Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (People’s Liberation Front, or JVP) swept through the towns and villages of this South Asian island of 16 million people.

The movement has now been decisively crushed by government security forces. However, many innocent people died in the process, victims not only of JVP terrorists but of shadowy vigilante hit squads now widely recognized to have operated with the sanction of some officials and politicians (see, In These Times, Sept. 13, 1989). Moreover, with many JVPers still at large, many Sri Lankans say a lasting peace will remain elusive until the government tackles the causes of the aborted uprisings.

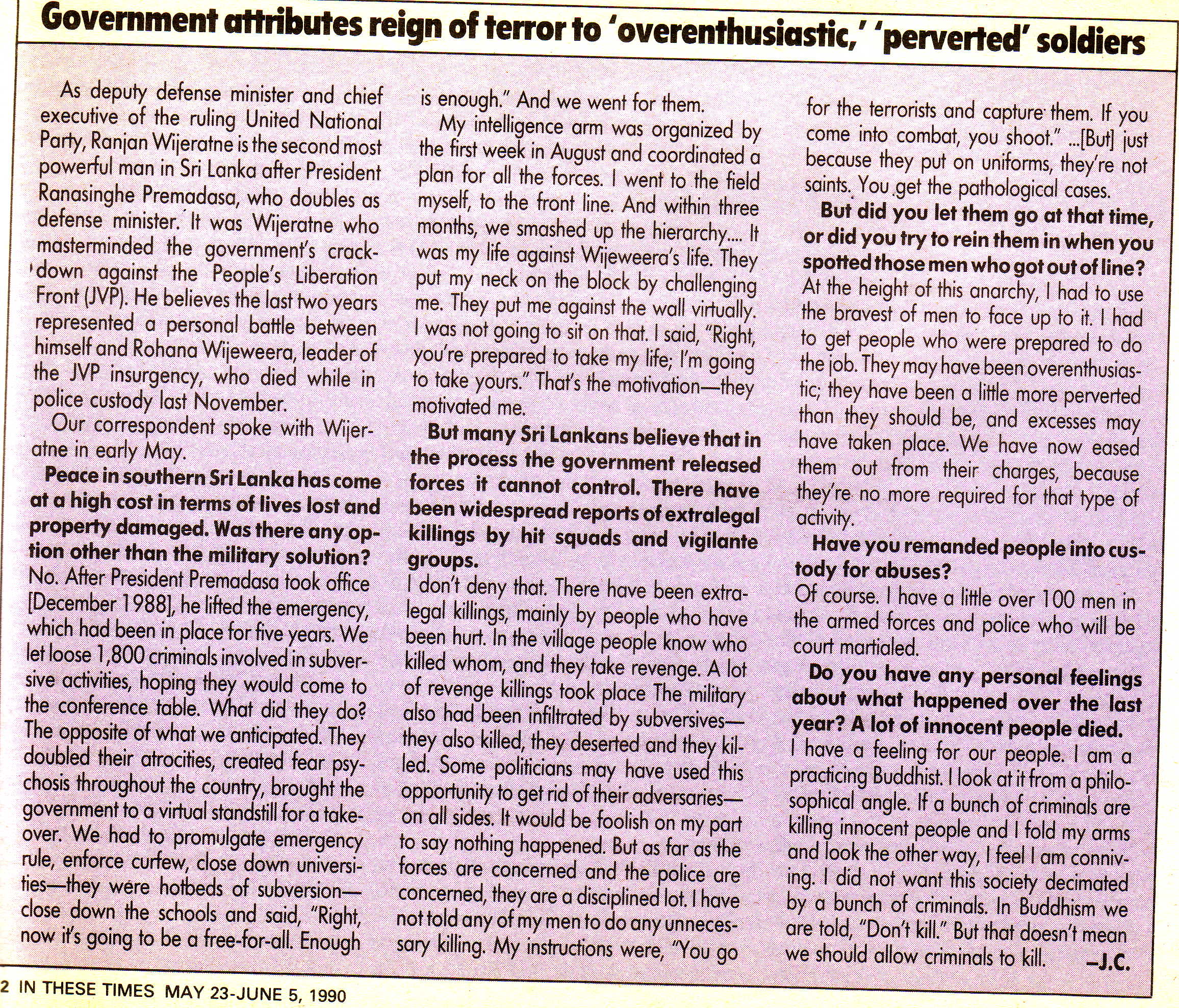

The JVP’s rise and fall: Founded in 1967, the JVP made a comeback two years ago by exploiting the nationalist sentiments of the majority Sinhalese over the stationing of Indian soldiers in the island’s Tamil-populated north and east under the 1987 Indo-Lanka peace accord. By July of last year, the JVP, using a combination of threats and brutal murders, brought the country and its economy to a standstill with a series of unofficial work stoppages. ‘Things got so bad,’ says Ranjan Wijeratne, plantations minister and state minister of defense, that ‘people thought the government would fall any moment.’

Under Wijeratne’s direction, the government security forces responded with a ferocity unknown in Asia since Indonesia put down a similar movement in 1965. At the height of the conflict last fall, as many as 50 people were killed each day, their bodies left burning under piles of tires by the sides of roads, in town squares or in schoolyards. The final toll is estimated to be as high as 30,000 civilians, according to military sources. The actual number will never be known, due to emergency regulations that allowed authorities to dispose of bodies without a public inquest. ‘One day they are going to unearth the remains of victims around police stations and army camps,’ says one resident of the south, ‘and it’s going to look like Nazi Germany.’

By December, security forces had wiped out most of the JVP’s top leadership. But the JVP is not dead. Military sources say that as many as 1,000 hard-core combatants are trying to reorganize from jungle bases.

‘The JVP is like a firebrand under the ashes,’ says one villager. ‘If the ashes are blown away, the firebrand could start again.’

A source close to the JVP says, however, that members who escaped the government’s dragnet have buried weapons and gone underground. ‘Given another three months,’ says a confident Wijeratne, ‘the so-called JVP will be virtually non-existent.’

In light of the improved security situation, President Ranasinghe Premadasa’s government has repealed many of the emergency regulations, including the ban on public meetings and the fight to enter private homes without a search warrant. The hit squads, according to politicians, have been disbanded. In early May, the government announced that all offensive military operations would cease ‘until further notice.’ At the same time, it has established independent surrender committees, made up of representatives of 10 political parties, which the government hopes will lessen the fear of insurgents still in hiding. The committees will review the cases of ‘surrenderees’ and release those who have committed minor offenses, giving them an official certificate of innocence. According to one committee member who reviewed several cases last week, about 30 percent of JVP suspects ‘didn’t know what they were getting into.’

Out of their minds: For its part, the army has also started a ‘hearts and minds’ campaign that, according to Secretary to the Ministry of Defense Gen. Cyril Ranatunge, is intended to show a still-fearful populace that ‘the security forces are concernedabout their well-being.’ As part of the campaign, the security forces have sponsored rock concerts in southern towns and organized development projects to rehabilitate hospitals and public buildings.

In Matara, where the troubles started, army officers tour villages with a video of the well-furnished safe house of the late JVP leader Rohana Wijeweera (though some say the army planted many of the items in the house – a refrigerator, imported liquor and a color TV – after Wijeweera’s death). In Gaul [Correction by Sachi: sic, Galle], the army has organized a training program for unemployed youth in vocations ranging from carpentry to auto mechanics, but Ranatunge admits that many are reluctant to apply because ‘they’re not quite sure if they will be locked up.’

Wijeratne says the government will lift the remaining emergency regulations as soon as it works out certain ‘legal details’ involving the 12,500 JVP suspects now held without being charged in army and police detention camps around the south. ‘We are trying to amend the laws to keep them in custody and take them to court,’ says Wijeratne. ‘Otherwise, we would have to bail them out.’

Among the more troublesome details is the question of whether confessions made under duress – read torture – should be allowed in court. So far, however, that hasn’t been a problem – the government has set up special courts, without juries, to hear their cases. Wijeratne says a little under 5,000 ‘will have to spend the rest of their lives in jail.’ Others are gradually being released or sent to rehabilitation camps for three to six months, where they receive vocational training in the mornings and while away their afternoons. Some are afraid of being on the outside. ‘A lot of people disappear as soon as they get home,’ says one detainee.

The leftovers: Some officials privately say that a military victory over the JVP will prove shortlived because of rampant unemployment and rural poverty, even worse in the wake of the war. ‘It’s very important that the government address itself to the political and social factors that led to the uprising,’ says oppositionist Chanaka Amaratunge. Chief among tem, says Amaratunge, is an extensive political patronage system that controls nearly every government job and once earned the ruling United National Party (UNP) the label of ‘Uncle and Nephew Party’. Letters of recommendation from UNP politicians, for example, are virtually a prerequisite for appointments and promotions in the civil service and security branches, all the way down to the village agricultural worker.

Political patronage, of course, occurs in every country. But the situation in Sri Lanka is aggravated by the country’s high literacy rate, second in Asia only to Japan, and the estimated 400,000 students who enter job market each year. ‘They can’t go back to the village,’ says Osmund Jayaratne, president of the Federation of University Teachers, ‘because they feel above it. And when they look for opportunity in the towns and do not find jobs or find jobs less than they think they deserve, they feel rejected.’

The most glaring example of patronage is the ‘job banks’. Established during the early years of UNP rule, the system required would be government employees to register for work. But the all-important forms were ‘notoriously in the hands of the ruling party member of parliament (MP),’ says Amaratunge.

Premadasa, to his credit, is now taking on the system – or at least parts of it. Earlier this year he abolished job banks and is now pushing for merit-based recruitment for government jobs. On another front, his government also plans to reorganize the educational system to set up more than 20 regional colleges to offer vocational training closer to home. And thye government is in the process of drawing up new election laws that will make it mandatory for 40 percent of all candidates in future elections to be between the ages of 18 and 45 years old.

Unfortunately, Premadasa has other problems. Having successfully stamped out the Sinhalese rebellion in the south, his government is threatened by the possibility of a new war in the island’s north and east, where most of Sri Lanka’s minority Tamils live. With the evacuation of Indian troops in February, the separatist Liberation Tigers of Tamil Elam (LTTE) are reasserting themselves and have taken almost total control of most of the Tamil areas. Two weeks ago, a Tamil MP who had opposed the LTTE was murdered in broad daylight in Colombo.

The toxic truth: ‘We’re dealing with a systematic and complex problem says the Peace Research Institute’s Jayaweera. ‘On the one hand, Sri Lanka is a post-colonial society trying to evolve as a nation, and, on the other, the country is a colonial economy trying to restructure itself to cope with the rising problems of rural poverty and unemployment.’

‘The process manifests itself as ethnic violence on one side and the JVP on the other,’ he continues. ‘The current preoccupation with violence and body counts is like complaining about the smell of a festering wound, when the problem is not the smell but the toxic substances that cause the infection.’

The violence that gripped southern Sri Lanka is now coming to an end. The roadblocks and security checks are gone and so is the ‘midnight knock.’ Foreign investors are showing interest in the country again. European tourist agents have already booked most of the island’s hotels for the fall season. And chances are good that next month’s rains will wash away the black charcoal stains still seen on the roads and beaches of a country once known to ancient mariners as ‘Serendib.’

********