The End of Sri Lanka’s Long Postwar?

by Jonathan Spencer, ‘Contemporary South Asia,’ UK, Volume 24, July 5, 2016

Securitization and its discontents the end of Sri Lanka s long post war

Abstract

In the 5 years after the 2009 defeat of the secessionist insurgency by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, the Sri Lankan armed forces expanded in numbers, moving into unexpected niches – tourism, urban planning, training university students. With the defeat of the Rajapkasa government in 2015, this process of ‘securitization’ or ‘militarization’ appeared to go into swift retreat. This paper considers the experience of the post-war years and asks what was permanent and what was less permanent in Sri Lanka’s post-war experiment in securitization. The paper is a revised version of the Keynote Lecture delivered at the 29th Annual Conference of the British Association of South Asian Studies, held at the University of Portsmouth in April 2015. The theme of the conference was the securitisation of South Asia.

Securitization and militarization

On 8 January 2015, President Mahinda Rajapaksa suffered an unexpected defeat in Sri Lanka’s seventh Presidential Election. After defeating the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in 2009, Rajapaksa’s regime had been associated with a rising tide of securitization, embodied for many in the actions and statements of his brother Gotabhaya Rajapaksa (GR), Secretary of the Ministry of Defence. The 2015 British Association for South Asian Studies (BASAS) lecture seemed to present an opportunity to take stock of this process, and in particular to cast a sceptical eye on the sense of inexorability that often seemed to accompany it, not least from its most vocal critics. What follows is a lightly edited version of my oral presentation, written within weeks of the change of government, an attempt if you will, to emulate Benjamin’s injunction to ‘seize hold of a memory as it flashes up’ (Benjamin 1969, 255). Other, more sober, accounts of the war and its aftermath will follow in the years to come.

The word ‘securitization’ in my title was taken from the theme of the BASAS conference, but the phenomenon I will sketch is as often referred to as ‘militarization’, as in Neloufer de Mel’s excellent Militarizing Sri Lanka (De Mel 2007). De Mel’s book was published towards the end of the hiatus in the open conflict that followed the Norwegian-brokered ceasefire agreement of 2002 between the Government of Sri Lanka and the LTTE. It did not – and could not – anticipate the escalation of the war in 2008 and 2009, nor indeed its final and even now still unexpected conclusion. In what follows, I am not going to go over that final story, which is beginning to get the chroniclers and analysts it deserves – I’m thinking of recent publications by Weiss (2011), Mohan (2014) and Keen (2014), for example. My topic is closer to Siddiqa’s Military Inc. (2007), which provides a detailed and compelling account of Pakistan’s military economy, although my analytical strategy is somewhat different from Siddiqa’s. The difference is not simply that my version is shorter. It is also that the phenomena I describe may turn out to be more ephemeral and shallow than the history Siddiqa charts in Pakistan. Or it may not. I will return to this question – which we can think of as the temporality of militarization – at the end of this article.

Figure 1. Gazette announcement of new ministries, 18 January 2015

I start with a document and a question. On the day of the Presidential Election in January 2015 billboards appeared in Colombo, uncaptioned, with images of the aftermath of horrifying moments from the war. They were, in a sense, the final word (or the final lack of words) in a strange election campaign, in which the incumbent regime first accused the opposition of threatening a return to civil war, initially with fanciful stories of the return of the vanquished LTTE, then with mobile screens which were set up in public spaces rerunning footage of the worst excesses of the war. Then, when the campaigning officially stopped two days before the vote, the government flooded the TV and newspapers with ever more grisly reminders of the war. Finally on polling day itself billboards appeared in Colombo with scenes from the dark days of the war, unaccompanied by any caption.

The document I want to discuss followed 10 days after Rajapaksa’s defeat. It is the Sri Lanka government Gazette of 18 January 2015 (Figure 1). It sets out the formal responsibilities of Ministries under the newly formed government. The full import of what has happened lurks deep in the detail. It starts with the Ministry of Defence. Its subsidiary responsibilities include the army, navy, air force, various defence colleges and a couple of spin-off companies. So far, so straightforward. Lower down, under the Ministry of Public Order, Disaster Management and Christian Affairs, we find the police and the department of immigration and emigration. Under the Ministry of Urban Development, Water Supply and Drainage, we find the Urban Development Authority (UDA). Nothing too surprising here (apart, maybe, from the baroque titles of the ministries themselves) except that the agencies I have highlighted – police, immigration and urban development – had been, until a week earlier, formally part of the ever expanding empire of the Ministry of Defence, which itself was firmly under the control of the President’s brother GR. For a few heady weeks after the election, the news was punctuated by announcements of other things the Ministry of Defence would notbe doing. The leadership training programme for undergraduate entrants to the country’s universities – a boot-camp for entire batches of would-be students, run by the security forces and intended to instil the kind of discipline that would put an end to ragging and protest on campus – was summarily discontinued. Urban development contracts would no longer be awarded to the army, except where there were significant cost savings, and even then soldiers would not be employed in menial tasks like the clearance of weed- and garbage-choked canals. The military training programme that gave school headteachers military ranks was suspended. It was reported (and subsequently denied) that the security forces had stopped checking vehicles at the last surviving checkpoint on the road to Jaffna and the north. And around this frenzy of demilitarization, the new government seemed determined to perform its own retreat from securitization: colleagues from the Federation of University Teachers Association, summoned to a meeting with the Prime Minister, were astonished to find themselves wandering unchecked into his official residence, with barely a soldier or policeman in sight.

So, on the one hand a government on the slide that seemed desperate to maintain the sense of a country at permanent war, and on the other, a new government, dismantling some of the more unlikely outposts of Sri Lanka’s experiment in securitization – securitization as political spectacle and desecuritization by bureaucratic reorganization. This raises the question: when exactly did the war end in Sri Lanka. Was it 19 May 2009, when Prabhakaran was killed, along with the remaining LTTE leadership (and an unknown number of others) in the final battle in the north? Or was it 8 January 2015, when Mahinda Rajapaksa was voted out of office, and his government replaced by a new, somewhat implausible, coalition, united only by the desire to appear as different as possible from its predecessor?

In what follows I explore answers to this question, applying equal amounts of scepticism not only to the more paranoid and teleological accounts of securitization that abounded in the later days of the Rajapaksa regime, but also to the breezy optimism of the post-election Colombo spring. After a very brief reminder of the history of the war, I consider the political economy of Sri Lanka’s experiment in securitization, and by way of a few specific examples, some of its more obvious consequences, of which, ultimately, discontent may have been the most significant.

When did the war start? The obvious answer is July 1983, when anti-Tamil violence, orchestrated by members of the ruling United National Party, sent young men in their droves into the hitherto tiny militant groups that had sprung up in Jaffna in the late 1970s. Others may prefer an earlier date – the attack on the Jaffna library in 1981, the passing of the Prevention of Terrorism Act and the declaration of a State of Emergency in the North in 1979, the murder of the Jaffna mayor by Prabhakaran in 1975, the police attack on delegates to the World Tamil Congress the year before and so on. In contrast the end might seem impressively clear cut: the death of Prabhakaran, and most of the remaining LTTE leadership, in May 2009, on a thin strip of beach hemmed in by water and soldiers on all sides This end, though, began counter-intuitively, with both parties signing up to a Norwegian-brokered ceasefire agreement in 2002. With hindsight it is easy to see this might end in tears, though few observers would have anticipated the strange dynamic instigated by the Norwegian intervention. By 2004 it was clear that the ceasefire had destabilized both parties: the LTTE was fatally weakened by the breakaway of a faction lead by its Eastern leader; Ranil Wickremesinghe’s government, under attack for its economic failings and its lack of patriotism, lost the parliamentary elections in 2004, and Wickremesinghe himself was defeated in the 2005 Presidential election by Mahinda Rajapaksa (aided by an LTTE-enforced boycott of the poll in the North and East). By late 2005 both sides were gearing up for what the LTTE fundraisers in the diaspora were billing as the ‘final war’ (Goodhand, Klem, and Sørbo 2011).

If much has been made of the success of the Rajapaksa team’s brutal no-holds-barred approach to counter-insurgency, the so-called ‘Sri Lanka’ solution, insufficient attention has been directed to the way in which the LTTE almost wilfully lost the war. From the restart of open fighting in July 2006, the government pushed the LTTE back from the territory it controlled, first in the East, then from 2007 in the Vanni region of the North. The LTTE’s attachment to its vision of territorial control (rather than the guerrilla attacks that had proved so effective against the Indians in the 1980s) exposed a new inequality in materiel, as its encampments were bombarded and its elaborate bunkers and fortifications were over-run. Starved of manpower with the loss of its traditional recruiting grounds in the East, and newly vulnerable to a government intelligence apparatus fed by former cadres from the breakaway Karuna faction, the LTTE blundered its way to defeat. As the civilian death toll mounted, both sides tried to appeal to the language of global humanitarianism: the LTTE surrounded themselves with civilians and made sure the civilians stayed with them, while their supporters outside Sri Lanka frantically called for a humanitarian intervention; the government, meanwhile, claimed it was engaged in rescuing the same civilian ‘hostages’. In the years after the last battle, official commemorations were called ‘Humanitarian Victory Day’.

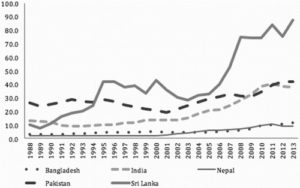

Figure 2. South Asia, per capita military expenditure 1988–2012 ($US). Source: SIPRI Military Expenditure Database 2012, http://milexdata.sipri.org.

Figure give some sense of the scale and consequence of the war itself. The first charts per capita military expenditure, from 1988 to 2013 (US$) (Figure 2).

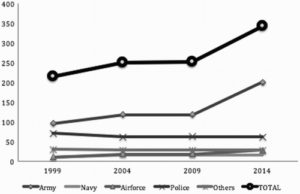

Figure 3 translates this military expenditure into people, the numbers in the security forces between 1999 and 2014. (There is no equivalent table for the numbers killed, whether for the LTTE, the government forces, or for civilians, and that is an absence that bears some reflection.)

Figure 3. Numbers employed in security forces (000s), Sri Lanka 1999–2014.

The chart starts a decade later than the previous one, in the years immediately before the 2002 ceasefire. After the ceasefire, the numbers in the security forces stay pretty even until the end of the war, when the army starts to climb beyond 300,000. The upswing in numbers that follows the end of the fighting is the topic of this paper. In what follows I will attempt to give political shape and meaning to what is here simply a line on a graph.

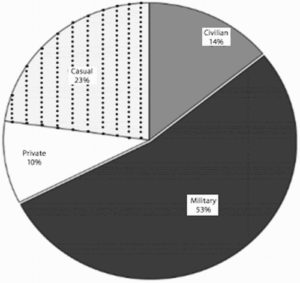

Before doing that, I have one more graphic. This uses data from 1999/2000, before the ceasefire, the return to war and the mysterious growth in peacetime military personnel. It comes from an article by Rajesh Venugopal, and summarizes a longer analysis from his Ph.D. thesis (Venugopal 2009, 2011). Venugopal analyses data from a country-wide World Bank household survey, to show how military employment is concentrated in the poor rural areas of the country’s north and east. The districts in question were the scene of grandiose state irrigation projects in the post-Independence years, but are now among the very poorest in the island (apart from the Tamil areas hit directly by the war). In the five districts highlighted in Venugopal’s analysis, just over half of Sinhala Buddhist men in cash employment between 18 and 30 work in some branch of the military (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Sources of cash employment for Sinhala Buddhist Men, 18–30 with 10–11 years of education (Ampara, Trincomalee, Polonnaruwa, Anuradhapura and Moneragala). Source: Venugopal (2011Venugopal, R. 2011. “The Politics of Market Reform at a Time of Civil War: Military Fiscalism in Sri Lanka.” Economic and Political Weekly 46 (49): 67–75. [Google Scholar], 73).

Grease devils and moral panics

If the figures provide some explanation for the lingering presence of the military in national politics, they do not in themselves tell us much about what this presence entails. In what follows I concentrate on two rather different sites of military activity, the Tamil-speaking areas of the north and east, and the prosperous city of Colombo on the west coast. In both cases I will be as interested in responses to military activity – the discontents of my title – as in the activity itself. In the first case, I partly rely on various secondary sources, and this tells us something about the phenomenon under discussion, especially the unsettling combination of the visible and the imagined in what we might call everyday militarization. In the second case, I will draw on research my friend and colleague Harini Amarasuriya.

Travelling up the A9 to Jaffna in 2012, for the first time since the war ended three years earlier, I was struck by a number of things: the quality of the new road (still under reconstruction at points); the speed with which the visible destruction of the war had been papered over in places like Killinochi (the former LTTE headquarters) – except for carefully preserved ruins being visited by the busloads of Sinhala tourists travelling north; the presence of the army and the absence of the army. As the road bisects the thinly populated scrub areas of the Vanni, it passes a sequence of huge military bases, often with victory monuments of one sort or another greeting passing travellers. But in and around Jaffna itself, the thousands of troops said to be still stationed in the area were often hard to spot, at least in the day time. At the same time, reports from agencies like the International Crisis Group (ICG), detailed a steady process of ‘militarization’ of the North, from routine surveillance of all manner of everyday activity, through the grabbing of land for commercial activity (run by the military), and the military-controlled settlement of Sinhala migrants in formerly Tamil areas. The government’s much-touted investment in Northern development was dominated by the military, and even local administrators like the Jaffna District Secretary, were subservient to the Presidential-appointed Governor, who, as in the East, was an ex-military man.

To all intents and purposes it looked as if this landscape had been politically tamed. There were no signs at all of a revival of the LTTE, and almost no expressions of visible protest against the military presence. This changed briefly, but in a rather extraordinary way, when in July and August 2011, two years after the end of the war, the island was swept by rumours, followed in some cases by vigilante attacks (including a number of killings). The rumours concerned ‘grease devils’, men who cover their half-naked bodies with grease in order to evade capture, and who lurk in the shadows, waiting to attack unprotected women. The rumours started in the central hills of the island, then moved to Up-Country Tamil workers on tea estates in the mountains, and then on to the Muslim and Tamil areas of the country’s north and east. Here they sparked confrontations with the police, the army and the navy.

The ‘grease devil’ is a folkloric figure, who hovers on the boundary between the human and the supernatural, sometimes being merely a sneak thief of women’s underwear, at other times attacking women and escaping pursuers with apparently superhuman leaps. There are versions of this figure in Southeast Asia – there have been sightings of an ‘orang minyak’ in Melaka in 2012 for example, not to mention a minor sub-genre of Malay horror movies from the 1950s on featuring the oily man. The 2011 sequence in Sri Lanka started with the mysterious murder of a number of elderly women in villages in Ratnapura district, in a predominantly Sinhala area. An army deserter was reported to have been subsequently arrested. Then sightings started to be reported across the south and central parts of the island, again in predominantly Sinhala areas, followed by vigilante patrols, and the capture and beating of various unfortunates. The first killings occurred on a tea estate near the town of Haputale, when two travelling salesmen were killed by a crowd of Up-Country Tamil estate workers. The rumours then spread to the Tamil and Muslim areas of the East. As the rumours hit the east, and then spread to the former LTTE heartlands in the North, anger turned almost entirely against the police and army. Grease devils had been seen coming from, or running back to, army bases. For the first, and so far only, time since the end of the war, the security forces found themselves openly challenged by angry protestors. Not only that, on two occasions members of the security forces were killed in the protests. Outside Trincomalee a crowd attacked a navy base, where a grease devil was thought to be sheltering. In Puttalam a policeman was killed. Then, as mysteriously as they had arrived, reports of the attacks declined and then stopped altogether within a few weeks.

Sensing they were losing control of the situation, the government responded with various statements which attempted to reassure the public and calm the situation. In one especially bizarre initiative, Muslim leaders from the north and east were summoned to the Ministry of Defence in Colombo to be addressed by the President’s brother who controlled that all-powerful ministry. From the viewpoint of middle-class Colombo, much of what was happening seemed alternately comic and frightening. There was endless speculation about what all this might signify, but no one among the usual (academic left-wing) suspects with whom I was hanging out actually believed there were ‘real’ attacks being made by ‘real’ grease devils. That is, until I spoke to a Tamil friend from the east, a seasoned observer and activist, who was as shocked at the suggestion that the attacks were not real as I was at her insistence that they were. For people living in the north and east, the rumours of predatory men attacking women did not represent a dramatic break from the ‘normal’ rhythms of life. Instead they were continuous with a history of sexual violence employed by elements within the military during and after the counter-insurgency against the LTTE. In the words of one activist quoted in an ICG report on women’s insecurity in the north and east, released a few months after the grease devil attacks: ‘You simply cannot have that many attacks without the endorsement of the security forces’ (ICG 2011, 37).

There is much that remains mysterious in the 2011 grease devil panic, as a recent article by Venugopal (2015) makes clear. But certain themes run through all the stories. As well as the dangers of predatory male sexuality, and the attendant vulnerability of unprotected women, there is the link to the military. In the south for pretty obvious reasons, the military uncanny is not attached to the actual soldiers who had fought the LTTE in the north, but instead to the murky figure of the deserter, who could be seen to embody in sublimated form the anxieties provoked by the ubiquitous military presence. In the north and east, there is no parallel embarrassment about seeing erstwhile heroes as threats, so the link is more direct: the grease devil is just the latest manifestation of a violent and threatening military presence. In both settings everyday militarization can be linked to a pervasive sense of insecurity, an insecurity which focuses on the threats to women posed by dominant versions of militarized masculinity, and which thrives in the atmosphere of uncertainty and rumour that has lingered long after the end of the war.

The military in the city

Much, much more could be said here, especially about the infrastructure of the military presence in the north and east, and the ebb and flow of everyday surveillance and harassment. What I have gestured towards is one aspect of what is routinely referred to as ‘militarization’ in Sri Lanka. It is (relatively) structured, and homogeneous in its ambitions. The agent of militarization is something systematic and impersonal: it is ‘the military’. It is not an agency that lends itself to ethnographic observation on the whole, and what sense we can make of it comes from the reports of external agencies like ICG. But there is another aspect of Sri Lanka’s long post-war in which ‘militarization’ has been seen very much as a personal, and personalistic, process. I refer to the role of Mahinda Rajapaksa’s brother Gotabhaya, who we just glimpsed in his meeting with the assembled Muslim leaders of the North and East.

GR served as an officer in the Sri Lankan Army in the 1970s and 1980s, and was actively engaged in both the early years of the war against the LTTE and the brutal suppression of the second Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna insurrection in the south. In the early 1990s he retired and migrated to the USA. When his brother was elected President in 2005, he returned to Sri Lanka to take up the position of Secretary to the Ministry of Defence. (The President held the formal post of Minister.) From this nicely ambiguous location – neither a serving military officer nor a politician, just, as he sometimes put it, a humble civil servant – he oversaw an immediate toughening in strategy against the LTTE, a toughening that eventually led to the 2009 victory. As the reach and ambition of the Ministry of Defence expanded under his command, so too did his public role, which over the years has sometimes seemed to eclipse that of his brother the President. As well as surveillance and governance work in the north and east, the military opened tourist hotels, golf courses and restaurants. When vegetable prices rose, they started selling vegetables. Colombo commuters could buy their lunchtime rice packets from military rice-and-curry stalls. University students were sent on ‘leadership training’ boot camps, run by the military and intended to foment the kind of discipline that would put an end to ragging and student protest. School principals were also sent for military training, returning to their schools with military ranks like captain or lieutenant. GR’s fame rose too. If his own increasingly fraught relations with the media were no’t enough to get him coverage, the Ministry of Defence website made sure his every thought and deed got maximum exposure.

In April 2010, the UDA, a legacy from President Premadasa’s work to upgrade low-income housing areas in the 1980s, was transferred to the Ministry of Defence, where it was immediately used as a vehicle for a project of aggressive ‘beautification’ of the country’s biggest city Colombo.1 Traffic laws were rigidly enforced for the first time in living memory, pavement hawkers cleared off the streets, stray dogs rounded up and disposed of, beautiful but insufficiently disciplined trees that lined many of the city’s older streets were removed to make way for new uniform pavements. Some old colonial buildings – the Dutch Hospital in Fort, the old Racecourse stand near the University – were rehabilitated and converted into sites for up-scale shopping and eating.

Describing the Greater Colombo Development Project in 2011, the Defence Secretary said that Colombo’s potential needed to be unleashed. Thus, the Greater Colombo Development Project includes repairing the drainage system, rehabilitation of lakes and urban wetlands, a new transport system, a new road network, building a new city on land reclaimed from the sea, and what is termed as ‘rationalizing’ land use and ‘freeing’ up land for development. While the ‘rationalizing’ of land use involves shifting key administrative units to the country’s capital complex at Sri Jayawardenapura Kotte, ‘freeing’ up land for development also includes relocating ‘slum dwellers’ in Colombo. Donors like the World Bank and JICA, the Japanese aid agency, allowed themselves to be associated with the parts of this plan that were deemed to be ‘purely’ infrastructural, while striving to disassociate themselves from the more controversial work of forced displacement.

GR’s personal mission to make Colombo into a world-class city has had mixed fortunes. His control of the military (and latterly, the Supreme Court) helped in facing down opponents, and for a time at least, created a sense of inevitability to accompany his adventures in urban development. New leisure spaces for the middle-classes have been created and for a time at least some three-wheeler drivers did routinely employ their meters to calculate fares. A number of areas of low-income housing were cleared, though more slowly than anticipated and not without opposition in the courts and on the streets.

Figure 5. Slave Island 2005. Source: Google Earth. Display full size

When Amarasuriya and I started trying to pin down what had actually happened in early 2013, we discovered that, despite press reports of thousands of evictions, at that point only a few hundred people had been removed from their houses. They were the inhabitants of Mews Street in Slave Island, whose houses had been summarily demolished a few weeks after the MoD takeover of the UDA in 2011. Elsewhere, in the wattes distributed across the city, people lived in fear of imminent eviction, but little happened despite GR’s belligerent threats, until 2014 when the streets around Java Lane in Slave Island were demolished and small shanty settlements were cleared in other parts of the city (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 6. Slave Island 2015. The expanded Defence Services College building can be seen in the top right quadrant. The suspended TATA building site, where Java Lana once stood, is in the top left.

statements at this time and which evokes the military man’s impatience with the indiscipline of the non-military world where citizens have a stubborn habit of ignoring the rules if it so suits them. Nothing better exemplifies this indiscipline than politics, and GR used his ambiguous position – not a soldier as such, but neither a politician – to project a sense of himself as a man who can get things done without worrying about the tiresome constraints of those who need at some point to mobilize the votes of the people affected by urban change. In the year before his brother’s electoral nemesis, there were persistent reports that Gotabhaya was preparing to formally enter politics, possibly as an MP for the Colombo area, probably as Prime Minister to his brother’s Presidency.

A third, and possibly crucial, aspect of the beautification project is Colombo’s ethnic demography. The centre of the city is not, in population terms, a Sinhala Buddhist space. The latest census figures give a population of 2.3 million for the larger Colombo District, which includes the surrounding suburbs, but only 318,000 for Colombo municipality itself. While the larger District is 77% Sinhala, in line with the national average, Colombo municipality is only 25% Sinhala, with Muslims (40%) and Sri Lankan Tamils (31%) the biggest ethnic component of the population. Here lies another source of discontent. Electorally, Colombo municipality had withstood the landslide of support for Mahinda Rajapaksa in the 2010 election, and had rejected his party in the 2011 municipal council elections. Behind the threats of eviction, for many, was the fear of what seemed to be an ambitious project of ethnic reorganization which would remake the city into the Sinhala Buddhist place it has never been before.

These fears were given added force by the emergence of new, aggressively hyper-nationalist groups, of which the Bodu Bala Sena (BBS, Buddhist Power Force) was the most high profile. BBS emerged in 2012 as a splinter from the Jathika Hela Urumaya, the party which had brought a group of Buddhist monks into parliament in 2004. In early 2013 it dominated the news through a sustained campaign against Muslims in general, and halal certification in particular. Widespread rumours that the BBS enjoyed the patronage and active support of GR were seemingly confirmed when GR appeared at the opening of a new BBS building and took the opportunity to defend the work the group was doing. After a series of attacks on Muslim businesses, there was a period of relative quiet, before June 2014, when crowds from a BBS rally in Aluthgama, south of Colombo, attacked Muslim houses and businesses, killing three Muslim men. Although the Special Task Force (the elite paramilitary wing of the Police) had been stationed in anticipation of trouble, they refused to intervene when the mobs attacked, proof for many of the security forces’ tacit support for the attackers.2

GR himself, in a number of interviews, seemed to endorse many of the BSS criticisms of the Muslim community, but in his public actions he alternated between identification with BBS, and interventions apparently intended to repair relations with those affected by their activities – after the security forces appeared to allow the crowds to destroy Muslim property in Aluthgama, navy personnel were sent to help in the rebuilding. How much the BBS did owe to the support and patronage of GR is still unclear, but many commentators have noted their near total eclipse since his loss of power in January, and drawn a rather obvious conclusion.

For all his public concern with discipline, GR’s own modus operandi as a public figure seemed more often to be improvisational to the point of impetuosity. Similarly, his experiments in militarization might have extended the reach of the military into hitherto untouched areas – schools, universities, rice-and-curry stands – but they did so in an uneven and often contentious way.

The long post-war ended?

Throughout the post-war period, there were rumours that senior figures in the military were concerned about the corrosive effects of forcing their soldiers to perform not merely civilian tasks, but often low-status civilian tasks like clearing canals or serving food in roadside stalls. If soldiers were serving rice packets to commuters, were the commuters being militarized, or was the military being domesticated? So, to return to my opening question, when did the war end? What do we make of the 5 years of post-war militarization that followed the crushing of the LTTE in 2009? Did the project of continuing militarization finally end on 8 January 2015 with Mahinda Rajapaksa’s electoral defeat, or is it still with us? I will first say something about the nature of the defeat, before turning to the questions.

Mahinda Rajapaksa, acting apparently on really bad astrological advice, but confident that a demoralized and endlessly out-manoeuvred opposition would present no challenge, called an early election for President late in 2014. Almost immediately the tables were turned when one of his senior ministers, Maithripala Sirisena, was announced as the much-anticipated common candidate who would stand on behalf of the otherwise disparate opposition forces. His central promise was a 100-day programme to dismantle as much as possible of the authoritarian structures, and corrupt practices of the Rajapaksa years. Quite soon, it was clear to his supporters that – with solid backing from Tamil and Muslim areas in the North and East, and enough support elsewhere, the maths were on Sirisena’s side. The only question was whether or not they would be allowed to win. What happened in the final hours of the Rajapaksa Presidency is murky and disputed, but it was widely reported that an attempt to halt the count and declare a state of emergency was blocked by the attorney-general, and the heads of the police and the armed forces, all of whom had been summoned to the Presidential residence.

There then followed the process of public dismantling that started with the Gazette announcements I cited at the start of this paper. The UDA was not merely taken away from the Ministry of Defence, it was allocated to a Ministry presided over by the leader of the Sri Lankan Muslim Congress. The security forces ceded their involvement in urban development, and in disciplining students and teachers, with not a murmur of complaint, and it is hard not to infer some degree of prior collusion between senior figures in the armed forces and the victorious opposition about the aspects of the militarization project that could be treated as disposable. These were essentially those aspects most closely identified with the figure of GR and his experiments in what we might call, after Hansen (2001), militarized anti-politics.

Other aspects of militarization, especially those that I sketched at the start of the paper, look to be more durable, for now at least. There were important concessions in the north: the military governor in Jaffna was replaced by a civilian and there is a real prospect that the devolved provincial council will be allowed to exercise some power. Some of the land taken by the military in the north has been handed back. The has been slower progress on the fate of detainees and the disappeared, but there have been some important symbolic gestures like the release on bail of the activist Jeyakumari Balendran in March 2015. But there were no immediate plans for a reduction in the size of the military budget and no obvious alternatives to Venugopal’s military fiscalism for the broken economy of the rural hinterland. Nor is it clear the army is ready to imagine an alternative to the huge deployments in former rebel areas, while we simply do no’t know what is happening with the attempts to pacify former rebel areas through the resettlement of poor Sinhalese emigrants by the army.

Figure 7. Rio complex, Colombo, September 2015.

The army presence in the north and east represents a deeper kind of militarization, which is unlikely to be evaporate in a haze of post-election optimism. The psychic discontents that found brief expression in the grease devil panic are also unlikely to disappear. The hidden wounds of years of war are still there in all communities and will be for years to come. But one thing I have learnt in these last years is the dangers of prognostication. When writing about the beautification project in Colombo, it seemed to me important to resist the temptation to concede that everything GR wanted to do he could and would do. One very obvious aspect of his project was the attempt to perform a certain omnipotence, and one danger for analysts would be that academic pessimism might unwittingly collude with the fantasies of the powerful.

In September 2015, after a further parliamentary election had confirmed that Rajapaksa’s regime was no more, I spent an afternoon at an extraordinary exhibition in a semi-ruined cinema complex in the heart of Slave Island. The Rio was built as a state-of-the-art cinema in the mid-1960s by a leading Tamil businessman. A 1970s modernist hotel was added to the complex a decade later. The hotel was attacked and looted in the July riots in 1983 and was left derelict and part abandoned until its takeover as a space for temporary art installations in 2014. The 2015 exhibition used the neglected bedrooms and corridors of the hotel for installations by individual artists from Sri Lanka and around the world. Many of the installations spoke to the recent history of the warand its aftermath, but the real star of the show was the wrecked building itself, with its smashed reminders of 30-year-old post-colonial glamour. On the top floor a sound installation created an especially eerie spectacle as young visitors, earbuds in place, stood transfixed, staring out at from the near ruined hotel at the new ruins of the beautification project (Figure 7).

Figure 8. Defence Services College school, from the Rio complex, Slave Island, September 2015

On one side were the stopped cranes and abandoned works of the TATA development project that was supposed to replace the demolished homes of Java Lane. To the north the skyline was dominated by the half-completed Lotus Tower, a Chinese-financed folly commissioned in the late days of the Rajakapsa government. And, next door to the hotel-cum-gallery stood another reminder of the unfinished business of securitization: the grandiose neo-classical school for the Defence College that had been extended over the former homes of the people of Mews Street. From the vantage of the Rio’s top floor, it was possible to see over the intimidating wall that surrounded the building. There was something odd about the higher floors of the new building. They were clearly unused and uninhabited – not the new home for the promised future, but instead a site of ‘suspension’, as Akhil Gupta has recently

put it (Gupta 2015). The building itself, seen from the neighbouring ruin, called up memories of the empty geometry and unhomely spaces in the paintings of Giorgio de Chirico. This vision of empty and pointless order, constructed on the rubble of a boisterously diverse neighbourhood and enclosed behind a thick wall, is perhaps as good a metaphor as any for the lasting effects of Sri Lanka’s experiment with securitization (Figure 8).

Acknowledgements

This is a revised and edited version of my lecture to the 2014 conference of the British Association for South Asian Studies. I am grateful to the BASAS organizing committee for the invitation, and to Tamsin Bradley and Naheem Jabbar for their warm welcome to Portsmouth and their patience with my plodding approach to editing my own writing. The sea shanties will linger long in the memory. John Zavos and a generous reviewer helped reduce the meanderings and inspired the use of Google Earth to chart the damage done to Slave Island sociality. In Colombo, Harini Amarasuriya has been a source of inspiration, information and enlightenment (not to mention dinner) through the post-war years.

Notes