by Sachi Sri Kantha, December 18, 2012

by Sachi Sri Kantha, December 18, 2012

Unlike the tone taken by many facultative memoirists who had poured out their sentiments on the recent death of sitar maestro Ravi Shankar on December 11th to the Hindu (Chennai) newspaper, strictly I avoid their style of presenting their reminiscences on how they had a brief (or lengthy) interaction with the Master. Of course, I did attend two of Ravi Shankar’s live concerts (one in Colombo, the other one when I was a student at the University of Illinois) for the thrill of it. But having been trained in Carnatic (Karnatic) Music, I failed to appreciate the nuances of Hindustani Music performed by Ravi Shankar. All I could infer was that he was hell of a musician and composer who was blessed with energy and passion.

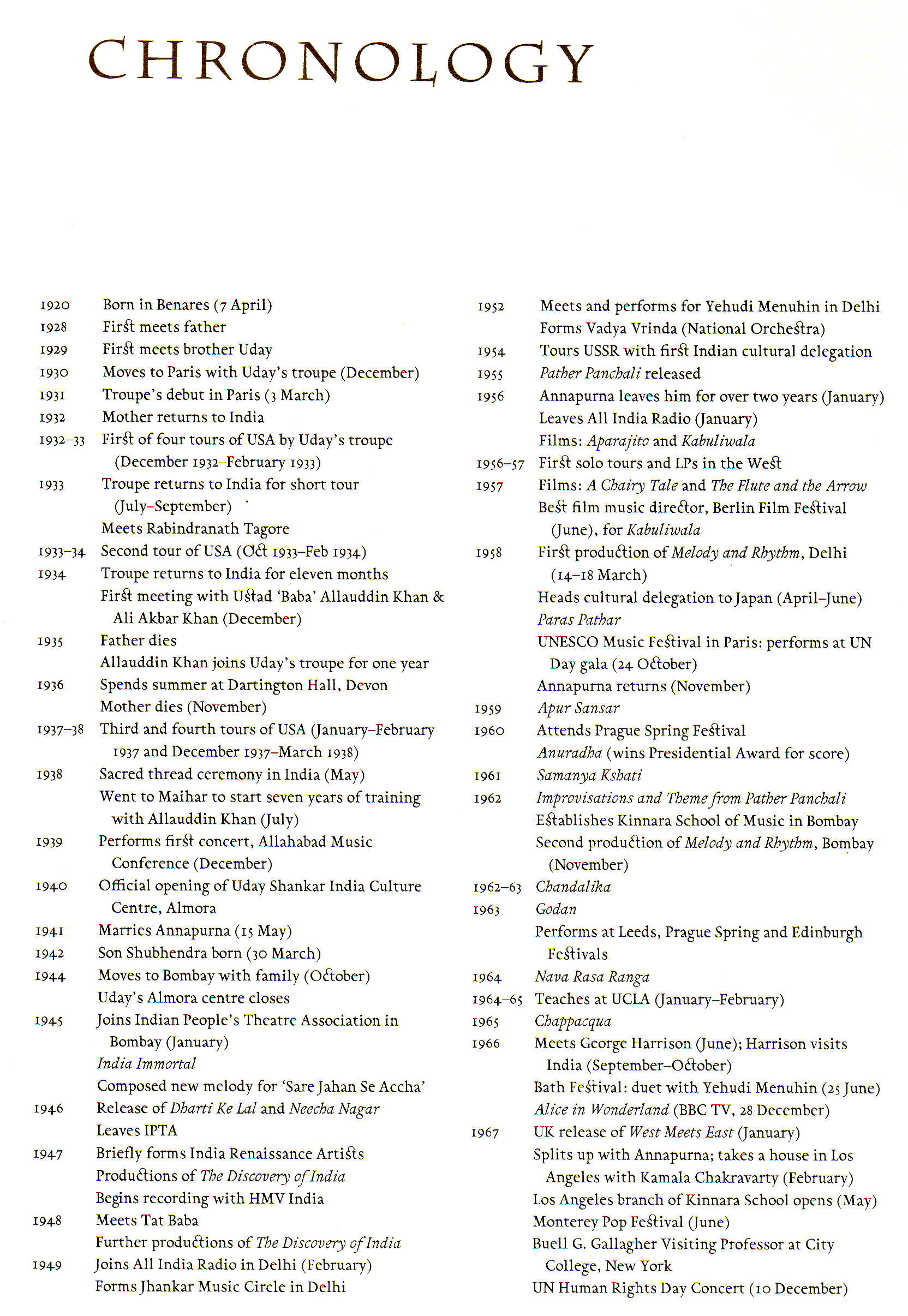

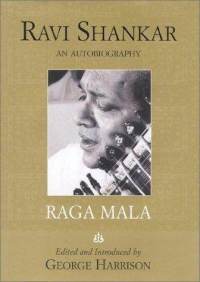

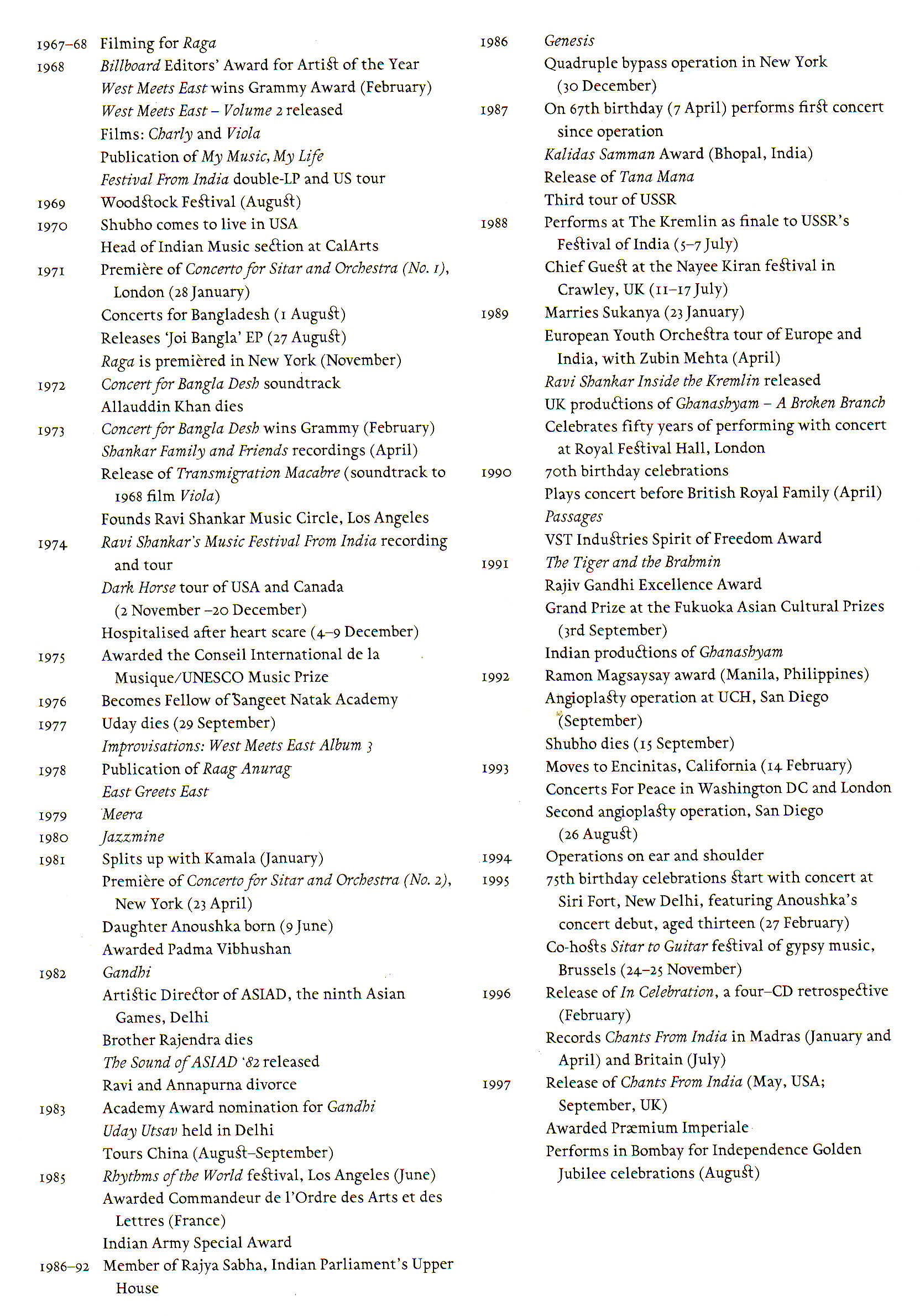

As such, I take an alternate route to pay my respects to Ravi Shankar. He was also a courageous autobiographer to record his life for posterity. As he himself had admitted in his preface to the 1997 autobiography, “To write a book on one’s own life is not an easy job.” I enjoyed reading his early autobiography ‘My Music My Life’(1968), more than 30 years ago. Subsequently, in 2005, I bought a copy of his second autobiography book Raga Mala (1997), which was edited and introduced by George Harrison (1943-2001), the lead guitarist of the Beatles group. Violinist Yehudi Menuhin (1916-1999) had contributed an ‘Afterword’ to the book. This 336 page work, includes a fine assemblage of vintage period photos of many personalities, who crossed Ravi Shankar’s life (see the scans of his life chronology). One can view this tribute as a laudatory book review of Ravi Shankar’s autobiography. I provide a few excerpts from this autobiography below.

Ravi Shankar had named 10 chapters for each raga. What is a raga? As Ravi Shankar explains in the glossary to his book, its ‘the melodic form at the centre of Hindustani and Carnatic classical music; the basis on which the vocalist or instrumentalist improvises in slow, medium or fast phases. A raga has five, six or seven notes in separate ascending and descending structures, and its own recognizable feature or theme. Each raga is associated with a particular time of the day or night, and has its principal rasa or mood.”

All these 10 ragas (Gangeshwari, Bairagi, Rangeshwari, Manamanjari, Suranjini, Kameshwari, Tilak Shyam, Jogeshwari, Mohan Kauns and Parameshwari) were Ravi Shankar’s own creations! Towards the end of the book (just prior to the index), one page provides a complete list of ragas (altogether 30) created by Ravi Shankar. The other 20 ragas include the following: Nat Bhairav, Ahir Lalit, Rasiya, Yaman Manjh, Gunji Kanhara, Janasanmodini, Mishra Gara, Pancham Se Gara, Purvi Kalyan, Palas Kafi, Charu Kauns, Kaushik Todi, Bairai Todi, Bhawani Bhairav, Sanjh Kalyan, Shailangi, Raja Kalyan, Banjara, Piloo Banjara and Suvarna.

Here are the 12 paragraphs which formed the candid preface of the book, which Ravi Shankar had aptly provided an alternate caption ‘Tuning Up’. He had written this in August 1997. The specific emphasis provided in large case letters, words within parenthesis and italics are as in the original. I do provide only one explanatory note within parenthesis, regarding Ravi Shankar’s second wife Sukanya.

“By nature I don’t think of the past; I think always of the future. Yet in my seventy-fifth year, the occasion for which this book was originally intended, there appeared to be some commotion being made about what I had achieved. This seems strange to me – although it makes me elated and grateful. I feel I have not been able to do more than a fraction of all the creative, musical and visual things that keep bubbling and brewing up in my mind.

And sitting here in Encinitas, California, in this lovely house with such beauty all around, I do feel that I would like to stay on this planet longer in order to accomplish as much as possible. One of my big motivations is my daughter, Anoushka, who has all the lakshna (signs) of being a yogya patri – literally a ‘suitable pot’. I want to train her and give her as much as I can, so that she can carry on and travel much further along the never-ending path of our great music.

People ask me always what I want to be remembered by, and I would like it to be not for my mistakes, but for the things that I was able to achieve – those that have touched the hearts of the people in my own country and beyond. God has been kind to me, and I have been very lucky indeed to have gained recognition and appreciation almost all over the world. It has been my good fortune that there have never been any problems with communicating the greatness of our music. In places where the people had never even heard of it, nevertheless it has been an instant success, and still there are warm receptions today everywhere I go.

Unfortunately, one faces a lot of discordant things in life. Previous negatives I have fought against and not been much affected by, but in these later years it has been much harder, mainly owing to health problems. Yet, being an Aries, even when I fall down I always bounce back on my feet quickly. A little frustration does creep in when I am not actively doing any new creative work, but things are looking better now, as I have recently been nurturing some new projects which seem to be coming into blossom.

I have found great relief and comfort over the last few years since I married Sukanya [Note by Sachi: nee Rajan, Ravi Shankar’s 2nd wife, is a Tamilian from Chennai]. Not only are we completely in love with each other, but she has also relieved me of all mundane and worldly worries, especially by cleaning up the materialistic mess I had created over many years. She can be a hard taskmistress on occasions, but is so tender and loving at the same time. Though it was late in my life that she became my wife, I am again thankful to God for bringing her to me.

I have found great relief and comfort over the last few years since I married Sukanya [Note by Sachi: nee Rajan, Ravi Shankar’s 2nd wife, is a Tamilian from Chennai]. Not only are we completely in love with each other, but she has also relieved me of all mundane and worldly worries, especially by cleaning up the materialistic mess I had created over many years. She can be a hard taskmistress on occasions, but is so tender and loving at the same time. Though it was late in my life that she became my wife, I am again thankful to God for bringing her to me.

To write a book on one’s own life is not an easy job, as I have, a myriad of characters and a jungle of events and incidents happening in different parts of the world. I have never been an organized person; even when I have tried writing a diary regularly, I have never managed to continue it for more than seven or eight days! Now, writing from memory, I have been reliant on some records, letters, newspaper cuttings, photograph albums and a few very dear people, such as my most senior students and elderly relatives and friends, whose help has been invaluable. Nevertheless there are bound to be inaccuracies in some places, for which I apologise – though I cannot help it. The book is also directed at a very diverse audience, and in many places I have attempted to be explicit in describing our Indian traditions. Naturally these details are intended mainly for non-Indian readers.

The whole project took over two years to complete, much longer than was expected. Even a professional writer takes months (or years) of undisturbed attention to finish a book, and here I have been entrusted with squeezing in such a challenging task between my travels, concerts, recording and editing sessions, practicing and teaching, while at times jet lag, tiredness or sickness have further burdened me. It has been a hard job, I tell you! But a rewarding one, too.

Then comes the question of being totally frank and writing everything: the TRUTH. That seems to be the name of the game today – and a big factor is that these titillating, lucid and sensational books sell well, too! Yet who doesn’t have a skeleton (or a few) in their cupboard? Don’t you? I believe in the middle path – though I have not always stayed on it myself – and have tried to say as much as is needed while avoiding anything hurtful to some people or in bad taste. There is a saying in Hindustani: ‘Samajhdaron ke liye ishara hi kafi hai’, meaning, ‘A hint is enough for an intelligent person to understand.’

And what is the truth, anyway? It is like beauty – in the eye of the beholder. The great Akira Kurosawa has shown this so wonderfully in his film Rashomon. Perspective plays a crucial role: I have tried to be as truthful as possible in stating the past and the present in relation to everyone and everything mentioned, including myself, but what I have told you here is the story of my life as I see it now.

There is no doubt that I have contradicted myself at many times and in many places over the course of my life. It will even have happened in this book, I am sure, because of how I have written it – in various places (California, Delhi, London, Glasgow, Henley and on several trains and planes), at various times (between 1994 and 1997) and in various ways (sometimes writing with a pen, sometimes dictating onto a tape, sometimes annotating drafts). We all contradict ourselves, and inevitably so. You can all too easily write an autobiography in which you praise one person to the heavens – your lover, your cook, or whoever – and omit to mention another person who was years ago the object of all your plaudits. In another ten or twenty years you may have a different partner, a different chef, a different perspective. Nothing is permanent in this life, and I can say this with the true confidence of one who frequently goes through changes of heart! Some of my views expressed here would have been different fifty years ago or twenty five years ago – or sometimes last week! I make no apology for this because it is unavoidable, but it is always worth bearing in mind.

The title of this book is Raga Mala – ‘Garland of Ragas’. Raga mala is a style of playing in which the performer refers to many different ragas while always returning to the main one. In a similar way, while writing this book I have time and again found that one recollection has sparked off another, which I might pursue before coming back to where I was. So perhaps you will find that reading this book is a little like listening to our raga mala style.

You will also notice that each of the chapters is named after a raga I have created. They are arranged in a sequence which follows the time theory associated with our North Indian classical music system, beginning with an early-morning raga, Gangeshwari (doubly appropriate since the river Ganga is the lifeblood of Benares, where my life began), through afternoon, evening and night ragas to Parameshwari, a raga of the very late night or early dawn. The epilogue is named after a dhun, a number in a lighter, folk style with which I usually end a concert.”

On Norah Jones (his first daughter)

When this book appeared in 1997, the fact that Norah Jones (born 1979, to Ravi Shankar and Sue Jones) was Ravi Shankar’s daughter was not public knowledge. He mentions in page 268 as follows: “She [Kamala Chakravarthy nee Sastri, who had a long term relationship with the sitarist] could not take it any more, especially when she learnt that I had a daughter in the West, born in 1979. (This was my first daughter. Her mother doesn’t want herself or her child to be identified with me or to keep in contact, and I have to respect their wish for anonymity.) Kamala left me at the beginning of 1981. It really saddened me greatly.”

Then again in the epilogue (written in August 1997), Ravi Shankar does mention Norah Jones as follows: “Recently I met my eighteen-year old daughter from the West, whom I had not seen for almost ten years. She spent a few weeks with us, including travelling on my European tour. There was such a mixture of pain and joy, for both of us. She is a fine musician, a jazz pianist. I do hope that we shall have a normal and happier relationship in the future.”

On Sri Lanka

Ravi Shankar makes a passing mention about Sri Lanka as follows: “Assisting me for Nava Rasa Ranga was Dr Penelope Estabrook. I had first met Penny in 1960 when I visited Sri Lanka, one of my favourite countries. It has a wide variety of scenic beauty, and the people are generally so likable – live-and let-live, happy go lucky types, fond of music and the arts. It reminded me of our own South Indian state Kerala. Lionel Edirisinghe, the late principal of the music college in Colombo, was a friend of mine who did much for the teaching and popularizing of Indian classical music there.”

On Carnatic Music

“The Carnatic system has provided me with a good share of my inspiration. I fell in love with Carnatic music in Madras at the age of twelve or thirteen when I first heard the great singer and veena player Veena Dham, grandmother of Bala Saraswati. After that the association with Bala and her guru Kandappan Pillai strengthened my ardour. As the first Hindustani instrumental musician to perform regularly in Madras, over many years I came to know all the great Carnatic musicians of their day, such as Tiger Varadcharya, Maharajapuram Viswanatham, Ariakudi Ramanujam Ayengar, the veena-player Karaikudi Sambashiva Aiyer, Palghat Mani on the mridangam, G.N.Balasubramanyam and a host of other giants. ‘GNB’ and I became good friends. I was lucky enough to receive admiration and love from all of them and from Madras audiences too.”

On Commercial Indian films

“The trend towards phoneyness in Indian films had already been established by then. Today it has been blown out of all proportion, almost ninety percent of them now being based on borrowed and concocted stories, with an unwarranted eight to ten songs and dance sequences. Fighting and violence have always been a feature of these films, and though (until quite recently) kissing and nudity have not been permitted on screen, the dialogue and lyrics have tended to be full of double entendres and vulagarity, as well as there being obscene dances and provocative exposures in costumes. These were (and are) designed as the only entertainment for the large section of the public that is repressed. Of course there have always been some eminent film-makers who occasionally make outstanding pictures. Especially since the advent of Satyajit Ray there have been a few directors in Calcutta, Bombay and Madras who have made some remarkable, world-class films, but usually they are not particularly profitable at the box office.”

In summing up, I’d state that this Raga Mala autobiography by maestro Ravi Shankar is a gem of a book and many fans of music in general, and Indian music in particular will treasure it.