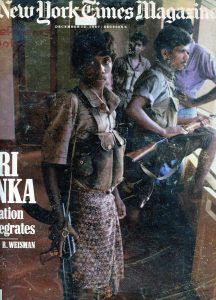

by Steven R. Weisman, The New York Times, December 13, 1987

IN AN ISLAND in a pristine lake near Colombo, the capital of Sri Lanka, gunmen guard the sleek new Parliament building, which a terrorist bomb ripped through last August, wounding the Prime Minister and barely missing the President. Downtown, the scattered vacant lots and burned-out buildings are remnants of the riots of July 1983, when hundreds of Tamils were pulled from their homes and burned alive, or hacked to death with axes in the streets.

At the ancient capital of Anuradhapura, the sacred Bo tree – grown from a cutting of the tree under which Buddha achieved enlightenment – is scarred with bullet holes, left from a 1985 attack by Tamil separatists in which 150 Sinhalese died. Throughout Sri Lanka, one sees the saffron robes of Buddhist monks. Traditionally an emblem of peace and tolerance; they have become symbols of militancy and martyrdom – especially after 29 monks were dragged off a bus last June, gunned down by Tamil terrorists and left to die in the dirt.

At the ancient capital of Anuradhapura, the sacred Bo tree – grown from a cutting of the tree under which Buddha achieved enlightenment – is scarred with bullet holes, left from a 1985 attack by Tamil separatists in which 150 Sinhalese died. Throughout Sri Lanka, one sees the saffron robes of Buddhist monks. Traditionally an emblem of peace and tolerance; they have become symbols of militancy and martyrdom – especially after 29 monks were dragged off a bus last June, gunned down by Tamil terrorists and left to die in the dirt.

Near the southern coast of Sri Lanka are blocks of drab concrete dormitories, a Sri Lankan Army camp in which Tamils – a Hindu minority in the country – are interned and, according to Amnesty International and Tamil spokesmen, regularly beaten, tortured and sexually assaulted. Farther up the coast is the burned-out shell of a house owned by a local minister, now occupied by a platoon of Sri Lankan soldiers whose task is to subdue Sinhalese terrorists, members of the island’s ethnic majority who oppose any accommodation with the Tamils. (A map is on page 85.) In the north and east of Sri Lanka, Indian troops patrol in jeeps and trucks – part of a 20,000-man foreign army that has joined the war against the Tamil guerrillas. In the once-bustling trading city of Jaffna, shattered storefronts and hollowed-out houses testify to the bloody days of October, when the Indians laid seige to the city -managing to capture it only after losing more than 200 men.

In Jaffna and other northern towns are enormous posters of fallen guerrilla heroes, their guns pointed into the air. The latest martyrs are 12 Tamils who, after being captured by the Sri Lankan Army in September, swallowed the cyanide capsules that all guerrillas wear around their necks.

When Sri Lanka was still called Ceylon – the change was made in 1972 – the name evoked an alluring paradise of misty hillside tea plantations and Buddhist monasteries, of pristine beaches and elephant sanctuaries. The country was led by one of the most civilized establishments in Asia, patrician heirs to a 2,500-year-old culture. As recently as the beginning of this decade, Sri Lanka was hailed as a model of economic progress and stability in the third world.

Now, after four years of bloody civil war, more than 7,000 Sri Lankans are dead, 500,000 have been routed from their homes and herded into refugee camps, and the island’s economy is in ruins. Hopes were raised last summer, when India sent in its army to enforce an accord between Sri Lanka and India to end the war. But the Indian ”peacekeeping” troops soon became caught up in their own war with the Tamils, the very people they were meant to protect. Today, Indian troops continue to battle the Tamils in the north and east, while the Sri Lanka Army occupies the south.

Now, after four years of bloody civil war, more than 7,000 Sri Lankans are dead, 500,000 have been routed from their homes and herded into refugee camps, and the island’s economy is in ruins. Hopes were raised last summer, when India sent in its army to enforce an accord between Sri Lanka and India to end the war. But the Indian ”peacekeeping” troops soon became caught up in their own war with the Tamils, the very people they were meant to protect. Today, Indian troops continue to battle the Tamils in the north and east, while the Sri Lanka Army occupies the south.

In Sri Lanka, there is no such thing as original sin. As with Northern Ireland, the Middle East and other historic areas of conflict, every atrocity is justified as revenge for an earlier outrage. The cycle of revenge has no end because it seems to have had no beginning.

Still, Sri Lanka’s disintegration reflects tensions found in many developing countries: the tension between economic development and economic equality, for example, and between a national commitment to democratic principles and an ethnic minority’s assertion of its rights. Most lethal of all, perhaps, has been Sri Lanka’s inability to balance its assertion of ethnic and religious pride with the ideals of pluralism and secularism.

IT IS NEARLY three years since I first visited Sri Lanka. The Tamil separatists who had been pushing for the establishment of an independent state in the Northern and Eastern Provinces of the island – ”Tamil Eelam,” or ”Tamil homeland” – were already waging a full-scale insurgency.

Independence Day came, and the Government agent – a Tamil civil servant named Marianpillai Anthonimuthu – made his way to an empty soccer stadium, surrounded by security forces, and defiantly raised the flag. ”We recognize we are potential targets,” Anthonimuthu told me nervously at the time. ”We get no protection. But still we do the job.”

Last October, Anthonimuthu was driving in an Indian Army convoy when a precisely timed explosion demolished his car, killing him instantly.

Anthonimuthu was only the most recent moderate Tamil official to be assassinated by Tamil extremists, who accused him of collaborating with the enemy. Sinhalese extremists, who oppose any accommodation with the Tamils, also specialize in assassinating Sinhalese leaders, as demonstrated most spectacularly in the bomb attack on Parliament last August. Since President Junius Richard Jayewardene signed a peace accord with India in July, no less than 50 activists in his ruling United National Party have been listed as murdered.

The image on the Sri Lankan flag raised by Anthonimuthu in that empty stadium nearly three years ago symbolizes the nation’s problem. The flag is dominated by a roaring golden lion – the emblem of the Sinhalese majority. According to the most recent census, taken in 1981, 74 percent of Sri Lankans are Sinhalese, 18 percent are Tamil and 7 percent Moslem.

AT ITS HEART, the story of national disintegration is the story of two peoples, two ethnic groups, each feeling increasingly threatened by the other, each driven to take action that can only reinforce the other’s fears.

Many say that race is the main source of the conflict. The Sinhalese, most of whom are Buddhist, trace their origins to lighter-skinned Indo-Aryans of Central Asia who migrated to Sri Lanka 2,500 years ago; the Tamils, most of whom are Hindu, are descended from the darker-skinned Dravidians of southern India, who are believed to have arrived slightly later.

In fact, today many Sinhalese are dark and many Tamils light; scholars believe the concept of two separate races is largely myth, that no single race can claim to have possessed the island first. Yet, when I asked a leading Buddhist monk to describe the source of the island’s separate identities, he told me it was race. Were the Sinhalese a superior race? ”All races feel superior to each other,” he answered. ”We are proud of our own race, but we don’t look down on others.”

Yet the Sinhalese, instead of viewing the Tamils as a minority on the island, tend to consider them a dominating majority – backed as they are by the 50 million Tamils living 18 miles away in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu.

The Sinhalese religious mythology contributes to their sense of siege. The earliest Sinhalese records tell how, 2,500 years ago, Buddha sent emissaries to the island to establish a place for his purest teachings. The most sacred place on Sri Lanka is a temple in the old mountain capital of Kandy, where Buddha’s tooth is enshrined.

”In this little country, history has given the Sinhalese race the position of being a majority with the characteristic of a minority,” explained Colvin De Silva, a Marxist political leader in Sri Lanka. ”The Sinhalese nurse this sense of peril, a belief that, like the Jews, history has vested them with a role of maintaining their traditions.” The island’s history is the story of Sinhalese and Tamil kingdoms rising and falling, clashing with one another, and together suffering a succession of invasions from the Indian giant to the north. Modern times brought new invaders: the Portuguese, the Dutch, and finally the British, who in 1815 imposed unity on the island for the first time in a thousand years.

Independence came in 1948; in the first flush of hope of a new nation eager to take its place in the postcolonial world, the Sinhalese and Tamil communities managed for a time to submerge their historic antagonisms.

Independence came in 1948; in the first flush of hope of a new nation eager to take its place in the postcolonial world, the Sinhalese and Tamil communities managed for a time to submerge their historic antagonisms.

But the potential for conflict was still present; indeed, it had been increased by an important legacy of the departing colonialists. British missionaries, who worried about angering the island’s Buddhist majority, found it easier to proselytize among the Hindus in Tamil areas. Many missionary schools were established in Tamil regions, and by independence the Tamils had parlayed this educational advantage, and their passion for hard work, into a dominant position in Sri Lanka’s universities and civil service.

But Sri Lanka’s modern political leaders were always upper-class Sinhalese patricians, many from landowning families of the old plantation economy of tea, rubber and coconuts set up by the British. Often more comfortable with the ways of their English colonizers than with their own culture, the ruling families enjoyed privileges because the Crown considered them ”natives imbued with the right spirit,” as Yasmine Gooneratne, a Sri Lankan literary scholar, puts it in her evocative memoir of one of the most powerful ruling families, the Bandaranaikes.

Mrs. Gooneratne recalls how the families of these would-be rulers traveled to London on ocean liners, wore Western clothes and took pride in their light-colored skin and plummy British accents. Many believed that British rule had essentially alienated them from the culture and people of their own country.

But a change in attitude came with a vengeance in 1956, when Solomon West Ridgeway Dias Bandaranaike was elected Prime Minister. Bandaranaike set out to restore dominance to Sinhalese culture, and his program showed the potential for a tyranny of the majority.

First, Bandaranaike made Sinhalese the sole official language of the nation, an act that was at the root of riots between the Sinhalese and Tamils in 1956 and 1958. Next, his Government imposed quotas on Tamils in the civil service, in the universities and elsewhere in the educational system.

The Government also embarked on a program to develop areas in the north and east of the island, resettling thousands of Sinhalese families in areas the Tamils considered their homelands. Demonstrations, riots and attacks continued; each effort to accommodate Tamil grievances failed. Each side accused the other of killing innocents.

Sri Lanka’s difficulties deepened during the 1970’s, as its economy sagged. Years of Government flirtation with socialism and increasing economic regulation had stifled investment and growth. It became increasingly difficult for Tamil and Sinhalese youths, even those with an education, to find jobs.

Compounding their disaffection were lingering resentments over caste discrimination, and the fact that leadership positions in both the Sinhalese and Tamil communities still tended to be held by upper-class, landowning families.

NORTH OF SRI LANKA’S central highland forests and tea plantations, the scrub jungles give way to sandy flat wastelands on which peasant farmers struggle to grow vegetables, chilis and tobacco. Along the coast of the Jaffna Peninsula, 20 miles from India, are a string of fishing villages that seem a world apart from the playing fields, law courts and prosperity of the capital of Colombo.

Velupillai Prabakaran grew up in one of those fishing towns, the son of a Government land officer. Deeply shy as a boy, he withdrew to read stories about the bravery of ancient Hindu warriors, Napoleon, and Indian fighters. He also learned from his family about atrocities against Tamils, such as the time in 1958 that some Sinhalese broke into a Hindu temple, tied a priest to his cot, poured gasoline on him and set him on fire.

”This left a very deep imprint on my mind,” Prabakaran once recalled. ”If such innocent lives could be destroyed, why could we not strike back?”

Today, Prabakaran – 33 years old, short, stocky, with a drooping mustache – is the supreme commander of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, a guerrilla organization of perhaps 2,000 men under arms, and with many thousands of supporters. Tamil leaders say that, like the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna among the Sinhalese, the guerrillas have drawn support from young people bitter about lack of job opportunities and resentful of leaders who they feel have been insensitive to their needs.

Known to his men as Thamby, or little brother, Prabakaran has spent most of the last decade underground, and has led his cadres by emphasizing self-sacrifice – symbolized by the cyanide capsules strung around their necks. From his troops, Prabakaran demands discipline, celibacy, adherence to a puritanical code forbidding drinking and smoking, and ruthlessness in battle.

During the 1970’s, the nascent Tiger movement carried out robberies and assassinations. But the movement reached a turning point when ”the boys,” as they are often called, began assassinating elected Tamil leaders who, they felt, had betrayed their people. In 1975, Prabakaran and two other young men ambushed the car of the Mayor of Jaffna and shot him dead.

One midnight late in July 1983, a group of Tigers led by Prabakaran faced the Sri Lankan Army in a shootout and killed 13 Sinhalese soldiers. Shock spread throughout the island; in Colombo and other towns, Sinhalese mobs rioted, burning and killing hundreds of innocent Tamil men, women and children. The riots, in turn, brought new support and momentum for the Tamil Eelam cause.

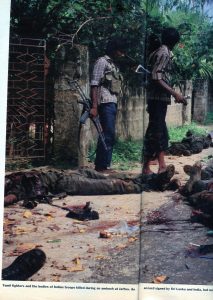

The pattern has continued, with each new attack bringing on a new retaliation. Sometimes the guerrillas would storm a police station. Sometimes the Sri Lankan Army would rampage through a Tamil town, shooting people, setting fire to houses, rounding up hundreds of young men.

As Tamil militancy spread, mainstream Tamil politicians grew increasingly impatient with Colombo’s slow responses to their appeals for justice. In 1983, the Tamil members of Parliament refused to take their seats, charging that President Jayewardene had reneged on promises to grant greater autonomy in Tamil areas.

The Tamil Eelam movement, meanwhile, had split into myriad factions that were soon waging a brutal war against one another. Prabakaran, who had a shootout with one rival in 1982, has been the most aggressive in launching attacks on other guerrilla groups. During the last two years, the Tigers have killed hundreds of men in two other Tamil Eelam organizations, accusing them of drug-running, shaking down merchants, robberies and other ”antisocial activities.”

THE TROUBLES OF Sri Lanka seem etched in the face of its President, 81-year-old Junius Richard Jayewardene. His is the ravaged countenance of a patriarch whose long career is rooted in a privileged childhood, followed by fiery campaigns waged on behalf of Sinhalese nationalism, and finally the agonizing struggle for accommodation of the last few years. Earlier this year, Jayewardene was asked why he had not moved more quickly to meet Tamil demands. The President shrugged; it was, he said, ”lack of intelligence, lack of courage, lack of foresight on my part.”

”For the last 20 years, there has been some discrimination,” Jayewardene acknowledged in a recent conversation at Ward Place, a spacious bungalow in a fashionable Colombo neighborhood. The house, surrounded by mango trees and frangipani shrubs, has been his family home for more than 50 years. ”We have corrected these defects. Of course, there were difficulties of implementation -there always are. But the Tamils were in too great a hurry. They were always being pushed from behind by the terrorists, who for no reason began to kill.”

The son of an eminent jurist, Jayewardene, who was called Dick as a young man, was a scholarly boy who played tennis and cricket, studied history and won many prizes for oratory.

In 1977, Jayewardene ran for Prime Minister, promising to revitalize the economy by restoring free enterprise and investment. His victory marked the first time a single party had achieved an absolute majority of the vote. He took advantage of his margin of victory by changing the Constitution, assuming the new position of President in 1978, and winning re-election by popular vote in 1982.

Jayewardene’s critics say he exacerbated the country’s divisions by blocking a new parliamentary election and, instead, pushing through a voter referendum that will keep in place the Parliament elected in 1977 until at least 1989. Although he claimed the referendum was essential because leftists were plotting to overthrow the Government, there were widespread charges of vote rigging, and many diplomats say the President simply seized on Sri Lanka’s turmoil as an excuse to subvert the country’s once-lively democratic processes. TO BRING AN END TO SRI Lanka’s conflict, Jayewardene had to recognize the reality of India’s involvement. For years, Sri Lanka had complained that India had provided sanctuary for and even training to the soldiers of the major Tamil insurgent organizations at bases in south India. The complaints were ignored, partly because the aspirations of Sri Lankan Tamils have long enjoyed great sympathy in the huge southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu and its capital, Madras. According to reports in the Indian press: years ago, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, seeking to shore up her own political support in Tamil Nadu, had authorized Indian intelligence agencies to assist the Tamils directly.

After Mrs. Gandhi was assassinated in 1984, her son and successor realized that the Sri Lankan insurgency might threaten the stability of southern India itself. Rajiv Gandhi had reason to be apprehensive about the possibility of an Indian-supported separatist movement succeeding in Sri Lanka. Among other things, his own attacks on Pakistan for supposedly aiding Sikh separatists in India began to look increasingly hollow as New Delhi uneasily rode the back of the Tigers.

In 1985, Gandhi declared that he was unequivocally opposed to the establishment of Tamil Eelam, and pledged to try to mediate a political compromise. The talks among the Tigers and Sri Lankan and Indian officials sputtered along for two years, gradually narrowing disagreements about how the island should be governed. Last summer, the sudden success of the Sri Lankan Army forced India’s hand. After years of military bumbling, the 30,000-man military had transformed itself -with some training and other assistance from several Western countries, including Israel – into an effective fighting force that for the first time seemed capable of achieving a military solution to the conflict.

During the last year, the Government forces managed to drive the Liberation Tigers out of much of the north and into the Jaffna Peninsula.

Last spring, Sri Lanka decided to try to finish the job, attacking the Tigers with helicopters and planes. In India, defenders of the Tamils cited news reports that hundreds of civilians were being killed, and accused Jayewardene of committing genocide. Gandhi intervened, airlifting 25 tons of food to besieged Tamil areas – in effect signaling Jayewardene that India intended to prevent him from crushing the Tigers by force.

The Indian action created a major crisis in Jayewardene’s Cabinet. Hardliners demanded the Sri Lankan Army continue the assault on Jaffna. Doves warned that might provoke an Indian invasion. The Sri Lankan Army chief of staff feared India might ship shoulder-launched antiaircraft missiles to the guerrillas, letting them shoot down Sri Lankan planes and helicopters. Without air cover, he said, Sri Lanka would have to abandon its effort to oust the Tigers from Jaffna. Presiding over a fractious Government, Jayewardene seized Gandhi’s offer to work out a compromise. ”I don’t mind giving in to India, I could not give in to Prabakaran,” he recalled, referring to the Tamil guerrilla leader.

Under the accord signed by Gandhi and Jayewardene last July 29, Sri Lanka agreed to grant greater political autonomy, including some local control of police and security forces, to Tamil areas in the north and east. In return, India persuaded the guerrillas to begin surrendering their weapons to the Indian Army.

Government authorities blame the resurgent People’s Liberation Front, the Janatha Vinukthi Peramuna, for the Sinhalese reaction. The front appears to have dropped its old Maoist rhetoric and taken up a nationalistic credo of Sinhalese identity under siege. According to Sri Lankan officials, the front has a wide following among trade union members, students, Buddhist monks, policemen and soldiers.

Despite the threat of Sinhalese reprisals, Jayewardene persuaded Parliament to fulfill the accord with India by granting limited political autonomy to Tamil areas. Whether the President can (Continued on Page 93) succeed in calming the Sinhalese majority, and quieting the misgivings in his own Cabinet, now depends on the Indian Army – and whether it can enforce peace in the north and east, then leave the island quickly.

THE ACCORD HAD one fatal shortcoming – it was never signed by the only party in a position to guarantee its success, the Tamil guerrillas. Prabakaran called it a ”stab in the back,” even while he pledged to turn over his weapons to the Indian Army. He felt compelled to yield to India’s considerable leverage – its ability to cut the rebels’ supply lines, as well as Gandhi’s promises of protection for the Tigers.

In September, the accord broke down. The Sri Lanka Navy, patrolling north of the island, stopped a suspicious-looking boat and found 17 heavily armed Tigers on board.

The Government charged that because these Tigers had not disarmed, they were not entitled to amnesty and must be conveyed to the prison camps in the south for interrogation. Among the guerrillas was a long-sought prize – the alleged mastermind of the massacre of 127 bus passengers in April. Rather than face what they said would be ”certain torture” in the south, all 17 Tigers swallowed their cyanide capsules. Twelve died. To Prabakaran, their suicide was dramatic proof of India’s failure to protect his men. The Tigers resumed their attacks on civilians, then began attacking Indian soldiers.

Gandhi knew that his army must respond, or else Jayewardene would order the Indian troops from the island. Gandhi authorized his army to disarm the Tigers by force – only to discover the limits of such force in a guerrilla conflict.

India, meanwhile, is learning the necessity of winning over hearts and minds, and developing an alternative civilian Tamil leadership willing to stand up to ”the boys.” Both tasks are proving extremely difficult.

The Tamil public seems to feel resentment toward the Indian Army; toward the Tigers they seem to feel a mixture of intimidation and respect. Tamil politicans say that though the Tigers might not win an election, they are widely admired as heroes whose stubbornness and sacrifices ultimately protected Tamil rights. Moderate Tamil politicians are thus reluctant to freeze them out of the process. And if they tried, they know they might be killed.

”We must face the fact that the Tigers can carry on their guerrilla war for a long time,” said Appapillai Amirthalingam, leader of the Tamil moderates. ”The only hope is for them to join in a political settlement. Instead, Prabakaran has overplayed his hand. He has brought this tragic situation on all of us.”

Yet despite India’s early offer to let the Tigers dominate an interim administration and even to oversee elections, Prabakaran continues to fight. After years of ruthless combat, years of hiding underground, the solitary guerrilla leader, many people say, has come to distrust politics and to fear for his life. He knows that rival guerrilla groups have targeted him for assassination. A journalist close to Prabakaran called him a ”haunted man” trapped by a ”paranoid” vision of the world.

”He sees the ghosts of his own men who died for a cause he cannot betray,” said the journalist. ”and he sees the ghosts of the men he has killed who want revenge.”

TODAY, VENGEFUL ghosts are everywhere in Sri Lanka. Perhaps the carnage could have been prevented; perhaps, had the moderates compromised earlier, they might not have lost control of events to the extremists, whose killings gave birth to the revenge-tragedy, which continues to feed on itself.

Still, it is possible to imagine that Sri Lanka will be permanently wounded. Already, people are whispering the unthinkable – that India may be unable to leave for many years, that it could finish by annexing the north and east of the island, following the precedent set by the ancient south Indian kingdoms that invaded the island more than 1,500 years ago.

The Tigers, too, are haunted by this history, seeing themselves as fulfilling the destiny of other ancient Tamil rulers in Sri Lanka -just as the Sinhalese look on themselves as heirs to their kingdoms of old.

It is a paradox that what hope there remains in Sri Lanka may spring from a new spirit of national identity that has been spurred on by India’s intervention. In private and in public, Tamils and Sinhalese agree on one thing – they don’t want to be dominated by India. One even hears a kind of perverse pride voiced by many Sinhalese in the Tamil guerrillas’ fierce resistance to the Indian Army.

How could peace be secured in Sri Lanka? Economic development must somehow be shared more equitably, avoiding the overlay of feudalism and caste; a national culture must be nurtured that threatens neither people.

But, finally, the only way Sri Lanka will achieve unity is by revising its view of history, by somehow rescuing the future from the gravitational pull of the past.

Steven R. Weisman is chief of The Times’s bureau in New Delhi.