This story appears in the November 2016 issue of National Geographic magazine.

The photograph the young woman holds is barely the size of a postage stamp. But it is the only one of her husband she could find here in her parents’ house. They had not approved of her marriage, given that he was just a fisherman from the coastal town of Mannar, while her family has lived in Jaffna, the capital of Sri Lanka’s Northern Province, for generations. But as the photo attests, her husband, a Tamil like herself—is broad-faced and confident. Staring at the tiny image of the man who went missing a decade ago, her mahogany eyes brighten as she loses herself in memories.

They’d fallen in love at a refugee camp in southern India in 1999, when she was 17. Both had escaped Sri Lanka’s wantonly vicious civil war, pitting the army, controlled by the majority Sinhalese, against Tamil rebels. She had fled Jaffna with her family, leaping over the corpses of neighbors as the military’s bombs plummeted from the sky. He had escaped Mannar after he saw an army officer shoot his youngest sister to death in their home. They had married under the withering glare of her mother.

They returned in 2002 to Mannar, where he could take his boat and his nets out to sea. They had a boy, then a girl. To supplement his modest income, he sold canisters of gasoline to Tamil resistance fighters. She saw little risk to this practice, which was common among Tamil men in Mannar. And when he said to her, “If something ever happens to me, you shouldn’t try to look for me—go back to your mother,” the words simply did not register, until December 27, 2006, when he took his motorcycle out and didn’t come back that evening or in the days that followed.

A rooster zigzags past her bare feet. Stirred from reverie, the fisherman’s wife puts down the photo and returns to the cooking chores with the other women in the ramshackle, barely lit house. Today her family has gathered to memorialize her mother’s sudden death from stomach cancer a month ago. One brother couldn’t make it. He’s in Paris, illegally and without a job. The Sri Lankan military had tortured him, and if he were to return home, he fears he might well be apprehended from the streets, as the fisherman was, as thousands of Tamil men have been—without warning, justification, paper trail, or even official acknowledgment.

Somehow the 34-year-old woman with the waist-length braided hair that sways as she serves a traditional vegetarian feast—chickpeas, eggplant, beans, tapioca—is not swallowed by grief. “I know my husband is alive,” she says, with simple finality. This belief is what preoccupies her. Not her mother’s death. Not that she earns almost nothing at the roadside kiosk where she sells rice and telephone cards. What matters most to the fisherman’s wife—who asked not to be identified out of fear for her safety and that of her family—is that she believes her husband remains a ghostly prisoner of a war that concluded seven years ago.

As it happens, the very same conundrum applies to Sri Lanka. In a sense it too has fallen off the map. Once seen as an emerging South Asian powerhouse, the island nation squandered its opportunity for international legitimacy when it descended into a spiral of violence fomented by long-nurtured ethnic grievances. Now, with a new government pledging to unite the country, that opportunity has returned. This April, Samantha Power, the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, applauded the administration led by President Maithripala Sirisena for its “extraordinary progress” in working toward “a durable peace, an accountable democracy, a new relationship with the outside world, and expanded opportunities for all.”

But it’s not Power or other foreign officials whom the government needs to win over. Far more crucial is the Tamil minority that feels left behind by the country’s postwar progress and embittered by the Sinhalese majority’s seeming indifference to its plight. And this is where the young woman with the tiny photograph comes in. The inescapable reality is that Sri Lanka will not fully reappear until men like her husband do.

Two-thirds of the way down the west coast of the teardrop-shaped island from Jaffna lies Colombo, Sri Lanka’s administrative capital. It’s a well-groomed, galloping metropolis that bears no visible scars of war. The city’s population of some 700,000 is more or less equally divided among Sinhalese Buddhists, Tamil Hindus, and Muslims, who live and work together with only occasional displays of hostility. For those who come to Sri Lanka full of questions about its future, Colombo offers reassuring answers.

The city maintained a surprising show of composure on the night of January 8, 2015, when Sri Lanka astonished the world by ousting the autocratic regime of Mahinda Rajapaksa through a largely peaceful and untainted election. Since that pivotal day, the nation’s new leaders have been eager to show the world that Sri Lanka can behave like a modern democracy. The Sirisena Administration has begun to reform the corrupt judiciary system, privatize bloated agencies, and reckon with immense debt incurred from dubious infrastructure contracts awarded to Chinese companies. “We’re not the same guys who used to tell you various things and then forget about it three days later,” said Harsha de Silva, the deputy minister of foreign affairs. “We want the world to know that we’re different—that we’re going to do what we say we’re doing.”

It’s entirely possible for a visitor to fly into Colombo, pursue the country’s myriad tourist pleasures—the ancient temples at Dambulla and Polonnaruwa, the elephants and leopards in its wildlife parks, the sumptuous tea plantations, the surfing mecca of Arugam Bay—and then depart a week or two later without the slightest awareness that for 26 years Sri Lanka was an epicenter of horrific ethnic bloodshed. But geography tugs the visitor away from seeing the lingering aftermath. Colombo is in the south—a region dominated by the Sinhalese, who are mostly Buddhists and constitute around 75 percent of the country’s population. Nearly all the country’s main attractions are also concentrated in the south. By contrast, the Northern Province is visually unremarkable, a mostly flat and arid expanse of agrarian terrain. It also happens to be the homeland of the Sri Lankan Tamils, who are mostly Hindu and make up about 11 percent of the population.

The north and east are where the militant Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (Eelam is the Tamil name for Sri Lanka) ran a de facto state until they were finally crushed. The battlefields across the north today are consecrated with towering memorials celebrating the defeat of “the terrorists.” But for these gaudy new spectacles, few tourists—including Sri Lankans living elsewhere on the island—would ever bother to visit the north. As one Tamil banker put it, with evident bitterness, “They come only to see the victory.”

“It’s a history of missed opportunities,” said Sri Lanka’s second most powerful government official, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe.

He was referring to the country’s as yet unfulfilled economic potential. Geographically situated at the busy trading crossroads between China and India, blessed with fertile land and an educated populace, the nation was positioned after World War II to compete with Singapore for the spoils of Japan’s momentary industrial demise.

Instead, the country known as Ceylon until 1972 proceeded to bungle its chances under a series of governments, including a failed experiment with socialism and, more recently, the cronyism of Rajapaksa, who ruled for a decade. His agriculture-based model purported “to be very populist,” Wickremesinghe said, “but wasn’t really giving anything to the people and was really meant to consolidate family rule.”

But Sri Lanka’s missed opportunities have not been limited to economic policy. Time and again, ethnic division has undone the country’s progress. For 133 years British colonizers tended to award upper-income jobs to Tamils while consigning Sinhalese to semiskilled labor. In 1948, when Sri Lanka won its independence, the new leaders didn’t try to unite the country. Sinhalese politicians nurtured the nationalist pride of the majority, who had arrived on the island around 500 B.C. and established what is now the world’s oldest continually Buddhist nation. They also stoked the majority’s abiding belief that Tamils had been awarded a disproportionate share of government jobs.

Systematically, the Sri Lanka government began to marginalize the Tamils: stripping the right to vote from those whose ancestors had been brought over from India to work in the tea plantations, reassigning university jobs to Sinhalese academics, and diluting the Tamil majority in the Eastern Province by offering land grants to Sinhalese. In 1956 the Sinhalese-dominated parliament made Sinhala the official language. While export-import licenses were preferentially granted to Sinhalese businessmen in the south, the government showed little interest in the Northern Province’s development.

In the 1970s the thought of secession began to take hold in the north, and the Tamil Tigers were born. In 1983 the Tigers ambushed and killed 13 army soldiers, spurring a backlash of ethnic riots in which thousands of Tamils were murdered. The Tigers retaliated with suicide bombers and massacres of civilians. Sri Lanka descended into civil war. Foreign investors fled the country, as did some three-quarters of a million skilled and semiskilled Sri Lankans.

Rajapaksa, who became president in 2005, escalated the war against the Tigers, and four years later government forces cornered the fighters and tens of thousands of Tamil civilians in a slender strip of land near a lagoon. By mid-May 2009 they had slaughtered the last remnants of the Tamil Tigers, along with thousands of the trapped civilians. The war was over. In the end as many as 100,000 people may have been killed.

The atrocities were by no means limited to one side. The Tamil Tigers infamously expelled more than 70,000 Muslim residents from the Northern Province in 1990. They forcibly conscripted thousands of Tamil youths. Their bombings of temples, trains, buses, and airplanes amounted to unambiguous acts of terrorism. After the Tamils were defeated, the triumphalist Rajapaksa regime continued its humbling of them. The government held Tamil political activists indefinitely without formal charges. It would “use the army to colonize the entire Tamil region and give it to the Sinhalese,” according to D. M. Swaminathan, a Tamil, who is the new government’s minister in charge of resettling Tamils forced into displaced persons camps. And it would refuse to acknowledge any role in the ongoing disappearances.

MINE REMOVAL: More than a million mines and other unexploded ordnance, from both sides of the conflict, have been removed, allowing resettlement in cleared areas.

TEA & TOURISM: Many Sri Lankan industries, such as its tea trade, are growing. Tourism revenue has more than quadrupled since the war ended.

DISPALCED: When the war ended in 2009, there were 44 centers for Tamils who had fled the fighting. Since then, the number has continued to decline as Tamils return home.

CHARLES PREPPERNAU, NGM STAFF

SOURCES: ESRI; USGS; NASA; MINISTRY OF DEFENCE, SRI LANKA; NATIONAL MINE ACTION CENTER; UN OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS; INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT MONITORING CENTRE; INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE FOR CLIMATE AND SOCIETY; FOUNDATION FOR ENVIRONMENT, CLIMATE, AND TECHNOLOGY; DEPARTMENT OF CENSUS AND STATISTICS, SRI LANKA

————–

Rajapaksa’s tyranny-of-the-majority vision for Sri Lanka was not sitting well with the international community. In 2010 the European Union halted the country’s benefits from certain sustainable-development and good-governance incentives on human rights grounds. Dissatisfied with the Rajapaksa Administration’s halfhearted war crimes investigation, the UN Human Rights Council commissioned one of its own in 2014. Under a withering spotlight, Sri Lanka seemed on the brink of yet another disappearing act.

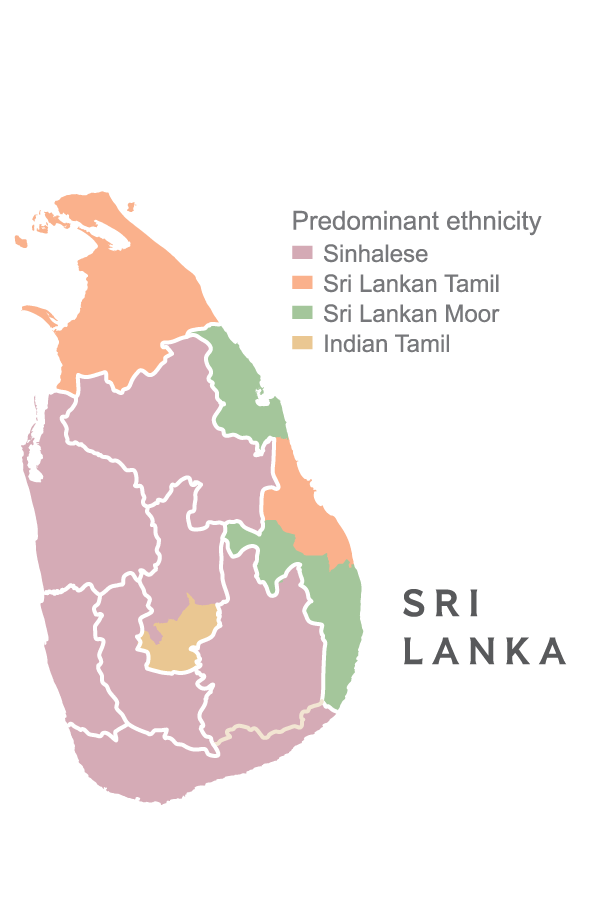

ETHNIC TENSIONS: A product of colonial policies, the resentment between Sinhalese and Tamils drove the civil war and has stymied reconciliation efforts needed to create lasting peace.

CHARLES PREPPERNAU, NGM STAFF,

DEPARTMENT OF CENSUS AND STATISTICS, SRI LANKA

I first went to the Northern Province at the end of 2014, just three weeks before Rajapaksa was voted out. The regime had grown annoyed with how journalists and UN investigators were depicting postwar conditions in the north and had effectively sealed it off. Gaining permission to travel there required months of haggling with the defense ministry. Finally, after obtaining authorization, my guide, interpreter, and I drove out of Colombo one early morning and, six and a half hours later, reached the first checkpoint, in the dusty village of Omantai, once the beginning of rebel-held territory. The army officers studied our papers, made calls, asked questions, examined our van, murmured among themselves, and at last grudgingly motioned us forward.

Throughout our 10-day stay, we encountered checkpoints nearly every hour. Soldiers demanded my guide’s home address and my (female) interpreter’s cell phone number. One officer called me late at night, sounding drunk, to inquire about my itinerary. Advised by confidants that those who spoke to us would likely be harassed by the military, we staged interviews furtively, in churches and in hotel rooms and in the van on the side of a desolate road. The Tamil homeland remained a thoroughly militarized zone.

Nearly a year later, 10 months after Sirisena became president, I returned. This time, no papers were required and no checkpoints greeted us after Omantai. Soldiers drove past us with disinterest. They did not linger on street corners, staring at Tamil passersby. In Jaffna there were no reports of newspapers being threatened or political demonstrations being quashed. Sri Lanka’s occupied territory felt, to a visitor anyway, more like a free society.

The Tamils I spoke with soon disabused me of my optimism. “There’s been some breathing space,” a Jaffna civic leader told me. “But it’s not a drastic change, I’m afraid.” Members of the government’s Criminal Investigation Department, or CID, still photographed participants at public meetings, he said. Similarly, Vallipuram Kaanamylnathan, editor of the leading Tamil newspaper, Uthayan, told me, “The press in the north doesn’t feel confident that they can carry out their job the way the media in the south does. The military is still keeping our office under surveillance.”

Today three-fourths of the country’s 200,000 armed forces remain stationed in the Northern Province. “That number won’t be reduced for a long time, because the threat isn’t 100 percent over,” said Gen. Daya Ratnayake, the former commander of the Sri Lankan Army. Many of the soldiers, Ratnayake pointed out, were now removing mines from the countryside, building temples and schools, and planting trees. But, as I would learn, they also operate the largest hotels in the Jaffna area. They run a golf course and a yogurt factory. They breed dairy cows and sell produce in the markets. “They’re getting free land and fertilizer, so they can sell for three rupees what a Jaffna farmer charges 20 rupees,” noted Swaminathan, the government minister. “So we have told the military very precisely that they have to give this land back over to the public.”

But the military—which until the 2015 election was headed by Rajapaksa’s brother Gotabaya—has been slow to respond to the new administration and continues to occupy some of the roughly 12,000 acres that it confiscated during the war.

“We have no confidence that we’ll get our land back,” said a 46-year-old Tamil woman who has lived in a squalid camp since the army seized her land in 1990. “They’ve built a hotel on my property. They’re earning revenue there. Are you telling me they’ll just hand it back over to us?”

The woman told me that her 20-year-old son was born in the camp. The rickety shack with the leaky roof and dirt floor is the only home he has ever known. “As you can see, this is no place to raise a family,” she said.

When I asked about her husband, she paused for a moment before replying, in a distant voice, “I lost my husband eight years ago. He was abducted in a white van.”

When the fisherman failed to return home, his wife’s first thought was that he must have taken his boat out—though it was odd that he wasn’t answering his phone. A few days later she found his motorcycle, and she went to the police. “If we hear of something,” they told her, “we’ll let you know.”

The fisherman’s wife, other women in Mannar, and women throughout the Northern Province whose men had disappeared decided to make themselves heard. They hectored the police. They visited every prison they could find. They traveled to Colombo and demanded an audience with government officials. They found nothing. Not a body, living or dead. Not an answer, or even a clue. And without formal acknowledgment that the men were dead, the women were not entitled to inheritances or bereavement benefits.

When the war ended, the women braced for answers. But none of the abducted men were released. Instead, the disappearances continued.

The fisherman’s wife wrote letters to Rajapaksa and Pope Francis. My husband has been missing since 2006, from an area controlled by the army. I have two young children. Please help me. Reports circulated of mass graves, of secret military camps. By 2015 the UN was estimating the number of Tamil disappearances at more than 15,000. Others in Sri Lanka suggested that this number was far too conservative. The Rajapaksa government, for its part, maintained that all the missing persons had simply fled overseas—a claim that it didn’t back up with any evidence.

In September 2015 the UN released a comprehensively damning assessment of war crimes in Sri Lanka, citing “years of denials and cover-ups” on the part of the Rajapaksa regime. By not protesting the findings, the new government implicitly signaled it was ready to confront the truth.

“We will get a second chance—we’re already working on it,” Wickremesinghe, the prime minister, told me. Crucial to this, he acknowledged, was an earnest attempt to make Tamils feel like part of a new Sri Lanka. “They just want to lead a normal life like everyone else,” he said.

I wondered how a normal life was possible for the 10 Tamil women I met whose loved ones had disappeared. They feared speaking openly, even under the new regime. The aunt of the fisherman’s wife has faced intimidation from state officials for filing a writ of habeas corpus on behalf of her missing son. Others have been threatened with arrest for staging protests. Meanwhile, dozens of Tamils in the north were rounded up this past spring and jailed without formal charges. The government’s continued surveillance of Tamil Hindus has coincided with the reemergence of Buddhist extremist groups thought to have been associated with the Rajapaksa Administration. This was, distressingly for many Tamils, still “normal life” in Sri Lanka.

A few days before meeting with the prime minister, I had seen the fisherman’s wife in Jaffna. There was now a new photograph of her missing husband, she had told me, from a newspaper story. It was of 168 men, all in white prison uniforms, seated and solemn-faced—taken at a penitentiary somewhere near Colombo during the annual Tamil harvest festival known as Pongal, which would have occurred 10 months earlier.

The men’s eyes were blacked out, and in the grainy copy the Tamil inmates seemed impossible to differentiate. But to a woman’s longing eyes, it was not impossible. “My husband is in that picture,” she had told me. “I can definitely identify him. Three other women from my neighborhood have recognized some of the men. Many of the men look like they have come from Mannar.” Seeing the doubt in my face, she had insisted, “I can identify him. He was my husband.”

But the prison was located. Her husband was not there. Nor were any of the other missing men from Mannar. And so I asked the prime minister if, as rumored, such men had been hidden in sites guarded by the military.

“There are no such places,” he said. “We spoke to the military. And that is what they said.”

“Meaning …”

“They’re all dead,” he said.

In June the Sri Lankan government acknowledged that more than 65,000 people have been reported missing since 1994. It also announced plans to create an office to investigate the disappearances and to issue “certificates of absence” to families of the missing so they can collect benefits and, hopefully, move on with their lives. Assuming it does so, perhaps Sri Lanka will also move forward—consigning its ghosts to memory.

Best known for her international news and cultural documentation, Ami Vitale has covered many subjects for National Geographic publications, including Kashmir, elephant-human relations, and man-eating lions.