by Somini Sengupta, ‘The New York Times,’ January 15, 2016

UNITED NATIONS — The images of gaunt, hollow-eyed children in three besieged Syrian towns this week prompted even the usually cautious Ban Ki-moon to bluntly and publicly declare that the people starving civilians on the battlefield were committing war crimes.

“Tomorrow,” Mr. Ban, the secretary general of the United Nations, warned, “there must be accountability for all those who play with people’s lives and dignity in this way.”

But Syria seems to have moved the needle on what is acceptable in war, and tomorrow’s chances of holding it accountable are as thin as ever.

The world’s most powerful countries have politicized the idea of international justice to berate their enemies and protect their allies — and there are indeed powerful countries backing some of the gunmen, government and rebel alike, who are preventing food from reaching the hungry in Syria.

The United Nations Security Council, which has the authority to refer the situation to the International Criminal Court in The Hague, made no mention of that possibility at its emergency session on Friday afternoon.

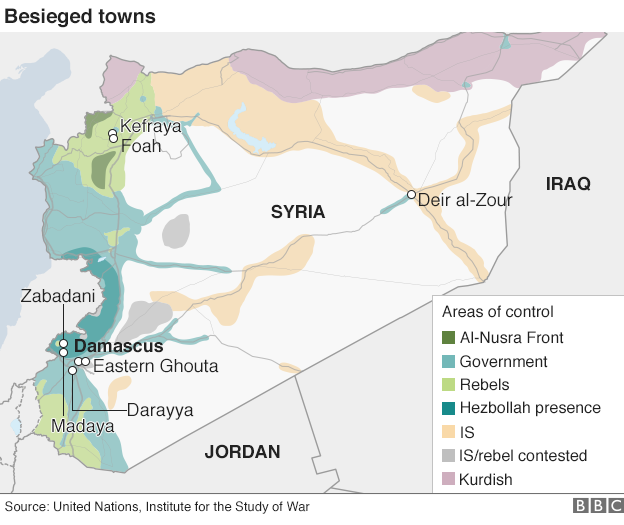

Map showing besieged parts of Syria, January 7, 2016

Not surprisingly, the United States and its Western partners used the latest reports of starvation deaths to hammer the Syrian government. Russia seized the occasion to scold rebel groups and went on to suggest that the attention to the humanitarian crisis — “all this unnecessary noise” is how Russia’s deputy permanent representative, Vladimir Safronkov, described it at the Security Council session — could derail the political talks scheduled to start Jan. 25 in Geneva.

Those talks, to be mediated by the United Nations, will bring together representatives of some of the very parties accused of using starvation as a weapon of war.

Mr. Ban encouraged the warring parties to lift sieges as “a confidence-building measure” before the talks. But he stopped short of saying that it should be a condition for those talks.

Starvation is one of many atrocities that have characterized the war in Syria. The United Nations-backed Commission of Inquiry has documented torture in Syrian prisons and government detention centers, extrajudicial killings by armed opposition groups and sexual enslavement by the Islamic State extremist group. Airstrikes have hit dozens of hospitals and medical centers.

Accountability is arguably more elusive than ever, given that both Russia and the United States are eager to push the warring parties to the negotiating table and deal with what they both see as an existential threat: the Islamic State. Syria is not a party to the International Criminal Court, which means that only the Security Council can refer the situation in Syria to the court.

The last time such a resolution was proposed, in 2014, Russia and China vetoed it. Few members of the Council, including France, which proposed the measure, believed it would be adopted. It was a way to embarrass the Syrian government, and, in turn, its most powerful backer, Russia.

The I.C.C. is not the only way to seek accountability for war crimes. A Syrian court could try suspects, but postwar tribunals are often seen as biased in favor of the victor, as in the case of Iraq after the ouster of Saddam Hussein. Also, under the principal of universal jurisdiction, people suspected of torture or other crimes against humanity can be arrested and tried outside their own countries, as with Chile’s former ruler Augusto Pinochet.

The attention to starvation as a weapon of war in Syria came this week as reports and stark images emerged of hungry civilians in Madaya, a rebel-held town encircled by government forces and pro-government militias.

Aid agencies that delivered two convoys of food and medicine said Friday that least 32 people had died because of malnutrition. Doctors Without Borders said late Friday that five people had died just this week, since the humanitarian convoys began bringing food into Madaya.

Syrian activists, including search and rescue groups that operate in opposition held areas, issued an appeal on Friday for relief supplies to be airdropped.

Wissam Tarif, of the rights group Avaaz, said, “Russia, U.S., Iran and Saudi Arabia are the puppet masters pulling the strings in Syria, and if the world is serious about getting the sieges lifted, then Ban Ki-moon needs to ramp up diplomatic pressure on them.”

He added, “Peace talks in Geneva are happening later this month, but peace is a pipe dream while children are being starved to death with impunity.”

The 40,000 people of Madaya are among 400,000 Syrians trapped behind front lines without regular access to food. Sieges have become “routine and systematic” in the five-year conflict, the United Nations deputy emergency relief chief, Kyung-wha Kang, told diplomats on Friday.

“You cannot let more people die under your watch,” she said.

According to Mr. Ban’s reports, of the 400,000 people cut off from regular deliveries of food, more than 180,000 are besieged by government forces and pro-government militias. Another 12,000 are besieged by rebels, including the powerful insurgent group Ahrar al Sham, backed by Saudi Arabia and Qatar. The United Nations says another 200,000 Syrians are trapped by the Islamic State in the town of Deir al-Zour.

Russia’s discomfort with the attention to starvation as a war tactic was on unusual display on Friday. “We urge the Syrian authorities to cooperate, constructively, with the @UN’s humanitarian agencies,” the foreign ministry said on Twitter.

It announced airdrops into part of Deir al-Zour, where the Islamic State has blocked relief for people under government control.