by Sachi Sri Kantha, June 25, 2016

Book Review

Parameswaran: Modern Tamils and Tamil National Question (Sri Lanka/Ilankai from 1796-2012), self-published, Mervena Printers, Chennai, 2013, 485 pp.

The information provided in the back cover of the book indicates, “N. Parameswaran after a career in international trade and a stint with UNDP/UNCTAD has devoted his time to write on aspects of the Sri Lankan Tamils’ history.” This is vital to comprehend this review. The author is a Tamil retiree, who is currently living in Australia, and constitutes a new category of expatriate Tamils who have time at their disposal and are interested in tracing their roots for sake of their own education, and to leave some record for their descendants as one of their achievements in life. Sincerity of author’s intention cannot be doubted. But, is sincerity alone adequate to tackle a theme as broad as scripting the history of Tamils in Sri Lanka from 1796 to 2012? We badly need amateur historians to present the Tamil viewpoint in a non-Tamil language, be it English, French, Spanish, Chinese, Arabic or Hindi. But, Parameswaran has gulped too much to synthesize the available material in a systematic, interesting output. Thus, this book is a disappointment for me.

The information provided in the back cover of the book indicates, “N. Parameswaran after a career in international trade and a stint with UNDP/UNCTAD has devoted his time to write on aspects of the Sri Lankan Tamils’ history.” This is vital to comprehend this review. The author is a Tamil retiree, who is currently living in Australia, and constitutes a new category of expatriate Tamils who have time at their disposal and are interested in tracing their roots for sake of their own education, and to leave some record for their descendants as one of their achievements in life. Sincerity of author’s intention cannot be doubted. But, is sincerity alone adequate to tackle a theme as broad as scripting the history of Tamils in Sri Lanka from 1796 to 2012? We badly need amateur historians to present the Tamil viewpoint in a non-Tamil language, be it English, French, Spanish, Chinese, Arabic or Hindi. But, Parameswaran has gulped too much to synthesize the available material in a systematic, interesting output. Thus, this book is a disappointment for me.

In 15 chapters and 480 pages, the book summarizes the story of how Tamils came to be incorporated as a minority ethnicity in the unified and unitary Ceylon (later Sri Lanka in 1972) during the British colonial period (1833-1947) and post-independence period (1948-2012). I cite a paragraph from the preface written by Sir Charles Jeffries, in his short book ‘Ceylon – The Path to Independence’ (1962; 148 pages), for its relevance.

“In Ceylon the British learnt, by trial and error, the art of colonial administration; but they learnt, also, the wisdom of relinquishing control when it was no longer tolerable by a people willing and able to maintain itself as an independent State. It was the example of Ceylon which made it possible for the peoples of Malaya, Ghana, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Tanganyika, and many other countries of the British colonial Empire to win their independence in their turn without revolution and without a breach of friendly relations.”

Jeffries should know. Between 1946 and 1948, he was “in charge, at the official level, of the work of the Colonial Office relating to Ceylon and was involved in the crucial discussions and negotiations which led to the grant of independence” to Ceylon. But the serious problem with relinquishing control of the island was that, in 1948, British did not leave the political power in the hands of indigenous people (especially Tamils in the North and East provinces), as when they entered the island in 1796! Due to this colossal error, all the ex-British colonies (mentioned by Jeffries above) continue to face problems in their post-Independent period.

Unfortunately, Jeffries and another British author Bertram Farmer (Ceylon: A Divided Nation, 1963; 74 pages) are two authors Parameswaran had failed to include in his bibliography. Attempting to be an amateur historian is one thing. But, ignoring the highly regarded previous authors who had tackled the same theme is another thing that cannot be treated cavalierly by a reviewer. In his book, Parameswaran laboriously describes the names and the activities of prominent Tamil political activists cum leaders of 19th, 20th and 21st century. These include, Arumuga Navalar, Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan, Sir Ponnambalam Arunachalam, G.G. Ponnambalam, S.J. V. Chelvanayakam, A. Amirthalingam and V. Prabhakaran. For this, he had depended on the standard works of few historians (G. C. Mendis, K.M. de Silva, A. Jeyaratnam Wilson, Jane Russell, S. Vythilingam, S. Pathmanathan, and M. Gunasingham) and journalists (M.R. Narayan Swamy and Anton Balasingham). This dependence, in some occasions have gone to an extent of plagiarizing sentences from previously published sources. I could locate at least five such examples from the works of K.M. de Silva, Jane Russell and M. Gunasingham.

Considering the professional expertise of the author in international trade, it would have been more optimal if he had limited his range to themes of his specialty, rather offering a digest of political events and describing the political peccadillos of guys like Varatharajah Perumal and Vinayagamoorthy Muralitharan (aka Karuna). In the 20th century, Tamils did contribute significantly to the industry, economy and trade of the island. Yet, the household names of Subramaniam Mahadevan and Sinnathamby Rajandram (founders of Maharaja Organisation), Sangarapillai Sellamuthu, Chittampalam Gardiner, A.Y.S. Gnanam, K. Gunaratnam, and Milk White soap K. Kanagarajah are completely missing in the text. For example, here is a passage.

“In July 1983, the government orchestrated the holocaust of the Tamils where over 3,000 Tamils were killed, some burnt alive. Electoral lists were used to identify Tamil homes. The police and army encouraged the killings. (Sivanayagam 1987).”

It would have been meritorious if the author had taken the trouble to accumulate the losses suffered by Tamil business magnates mentioned above. There occurs a citation to Sivanayagam’s 1987 work. But, one cannot find details about this Sivanayagam’s work in any of the pages in the book. Such a sloppiness dominates this book.

Here are some incorrect factual details which deflates the reliability of the book. (1) Alfred Duraiappah’s assassination was dated to 1973. It happened in 1975. (2) The assassination of TULF parliamentarians V. Dharmalingam and M. Alalasundaram in 1985 was wrongly attributed to LTTE. In fact, it was carried out by TELO militants, at the instigation of India’s gumshoes Research and Analysis Wing (RAW). This had been mentioned by M.R. Narayan Swamy’s book, ‘Tigers of Lanka: from Boys to Guerillas’, which the author had included in his bibliography. (3) American diplomat/ambassador and academic W. Howard Wriggins is misidentified as “journalist W. Howard Higgins”! (4) In more than one instance, author regurgitates the misinformation promoted by the Indian gumshoes and the Colombo media that when Karuna quit LTTE in 2004, he “disbanded 6,000 of the cadre under his command and sent them home”. Subsequent developments in Karuna’s politics (from 2004 to 2016) revealed that his influence as a Tamil leader was measly to the size of a rat (Eli, in Tamil) and not elegant as that of a tiger (Puli, in Tamil).

Parameswaran’s three recommendations to solve the problems facing Sri Lankan Tamils are as follows:

Parameswaran’s three recommendations to solve the problems facing Sri Lankan Tamils are as follows:

First: “To urge the GOSL to implement the ‘constructive recommendations’ of the LLRC as accepted in the US sponsored resolution in the UNHRC in March 2013.”

Second: “To press the international community to request the UN Secretary General to now act to set up an independent international investigation of the war crimes…”

Third: “To urge for an UN sponsored referendum, East Timorese/South Sudan style to be held to enable the Sri Lankan Tamils at home and abroad to express their right of self determination…”

This phrase ‘international community’ (IC) is sprinkled infrequently in the book, as if it will be a panacea if these omnipresent demigods will listen attentively to the pleas of hapless Tamils. But Parameswaran fails to identify distinctly who comprise this so-called IC. The last sentence of the book reads, “It is again the international community and India who can bring the necessary pressure to bear on the GOSL and directly intervene to compel Sri Lanka to fall in line and cooperate on all three areas of action referred to above.” How about my choice phrase ‘Image Crooks’ for IC? Should one consider the human right organizations (example AI or HRW), the intelligence gumshoes (example, CIA, MI), media outlets (example BBC) as IC? All these agencies have their own agenda in advancing the interests of their sponsors and puppet masters. They are not headed by folks with ‘Mother Teresa mindset’. And, in my biased view, trusting ‘Mother India’ to “bring necessary pressure to bear on the GOSL” is like a fool’s dream because after the death of Indira Gandhi in 1984, there aren’t any powerful leaders in India who have the guts to make such a daring decision.

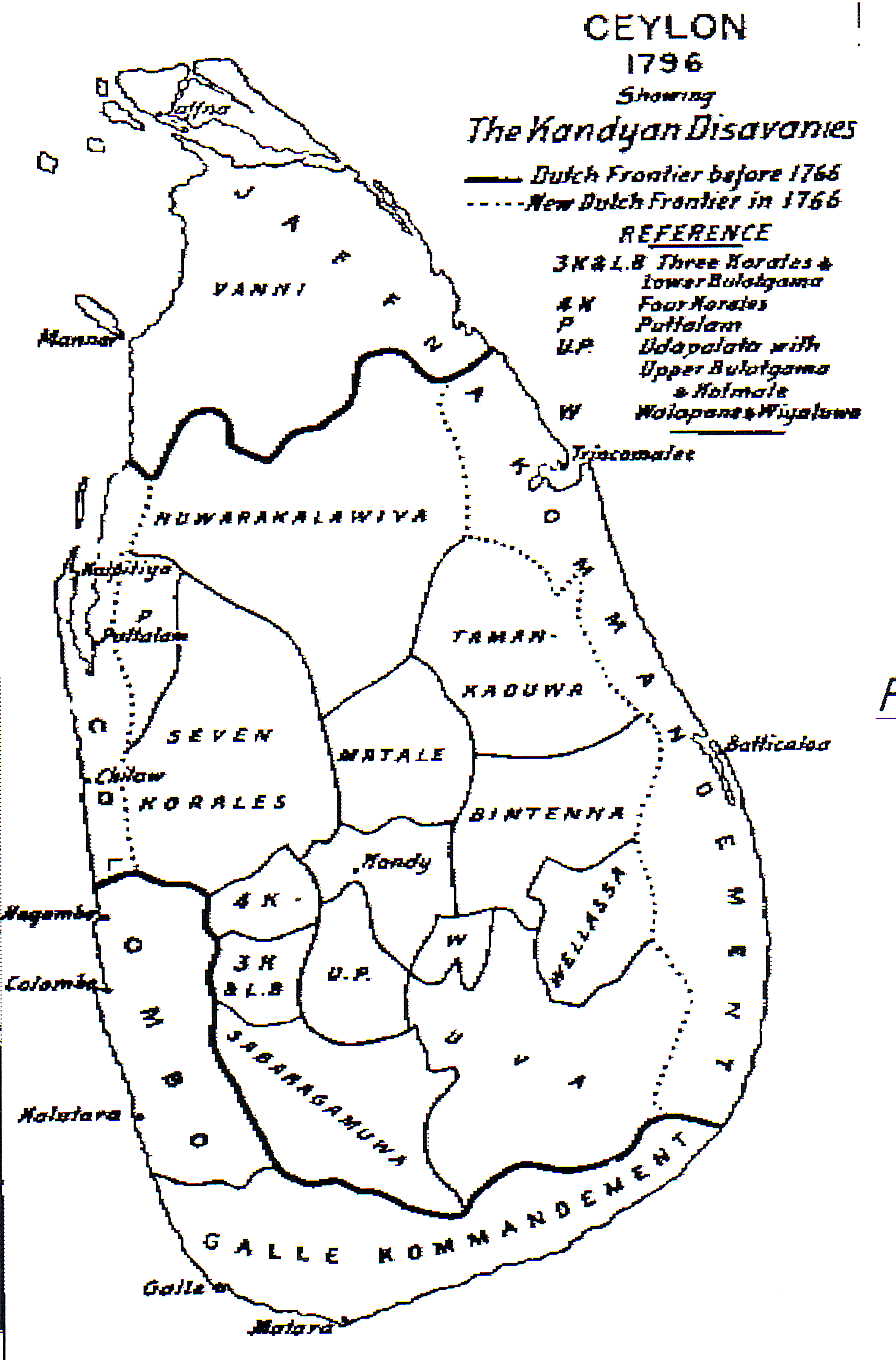

For some reasons, available diverse viewpoints from Tamil angle on the plight of Sri Lankan Tamils have been ignored by the author. His assembled bibliography exclude the names of S.J. Tambiah, K. Sivathamby, S. Sivanayagam, T. Sabaratnam, Taraki (D. Sivaram), Sachi Sri Kantha, Adele Balasingham, Radhika Coomaraswamy, Peter Schalk, Narasimhan Ram, and V. Suryanarayan who have written prolifically on this theme in the print and digital media. This is why, this book fails to click as a reliable history source on Sri Lankan Tamils. Lack of an index, for a book of 480 pages, is a demerit too. Also the included maps, photos and figures collected from internet are of poor quality.

Fifteen years ago, I asked my Japanese students to answer a simple question, ‘What is truth?’ I was enamored by the response of one woman student. Her response was, “I think the truth is like a ghost. Everybody knows this word. But nobody can say clearly what this is. Each people have their own vague form of truths. Although truth often helps people, it also hurts them. And truth sometimes disappears. After all, truth is a ghost.” This answer neatly sums up the identity of ‘international community’, and simply put, the IC hardly cares about the truth in Sri Lanka at all. In my biased view, what many Tamils like Parameswaran naively consider as major players of the IC (viz. politicians, media and human rights activists in USA and UK) are more interested in covering their derriere for their lapses of error, than in aiding the hapless Tamils. Here is a realistic example. Gotabhaya Rajapaksa is a US citizen. Whatever crimes he had committed against the Tamils, this US citizenship shields him from any punishment from an international court. Uncle Sam’s decision makers will see to it that G. Rajapaksa will not be brought to an international court of justice, for the simple reason that this will set a bad precedence for other criminals who will be hounded for their committed crimes in lands beyond the borders of USA.

I’m sure that many readers will sympathize with the story presented by Parameswaran. In the post-independent period of Sri Lanka, Tamil ethnics (both indigenous and recently Indian-origin) have been treated like ‘garbage’ by the Sinhalese political leaders. Essentially, there are four routes of disposing ‘garbage’; burn, reduce, recycle and dump. Quite a percentage of Tamils have been burnt in the anti-Tamil pogroms that occurred in 1958, 1977 and 1983 as well as in the Eelam Wars I, II, III and IV. Another segment have been ‘reduced’ by genocidal military recruitment policies, since 1979. A third segment have been ‘re-cycled’ by ethnic mixing or political puppetry from ‘Tamil’ collaborators. The remaining segment have been dumped in other countries as refugees. This story deserves repetition by other competent historians.