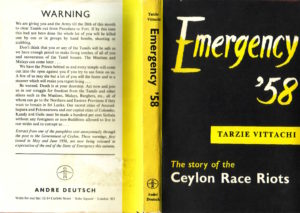

Excerpts from Emergency’58, The Story of the Ceylon Race Riots by Tarzie Vittachi, Andre Deutsch, 1958, courtesy TamilNation.org

“The Prime Minister, Mr S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike, continued with his year-long efforts to convince the people that the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayakam Pact which he had made with the Federal Party a year ago, was a fool-proof solution of the Communal Problem, inspired by his understanding of the doctrine of the Middle Way. For instance, a newspaper reported:

“The Prime Minister, Mr. S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike, presiding at the prize distribution of the Sri Gnanaratna Buddhist Sunday School, Panadura, said that knotty problems of State had been successfully tackled by invoking the principles and tenets of Buddhism. ‘The Middle Path, Maddiyama Prathipadawa, has been my magic wand and I shall always stick by this principle,’ he said.” (Ceylon Daily News.)

The yes-men round him smirked complacently whenever he referred to his Magic Wand for solving problems in that special tone of voice which accompanies a double entendre.

Mr Bandaranaike said much the same thing when he justified the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayakam Pact at the Annual Sessions of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party held at Kelaniya on March 1and 2 (1957). The relevant section of his Presidential Address is:

“In the discussion which the leaders of the Federal Party had with me an honourable solution was reached. In thinking over this problem I had in mind the fact that I am not merely a Prime Minister but a Buddhist Prime Minister. And my Buddhism is not of the “label” variety. I embraced Buddhism because I was intellectually convinced of its worth. At this juncture I said to myself: “Buddhism means so much to me, let me be dictated to only by the tenets of my faith, in these discussions. I am happy to say a solution was immediately forthcoming.” (Sunday Observer, March 2, 1958.)

But the oftener he defended the B-C Pact the clearer it became that, in the Prime Minister’s own opinion, it needed defending. The longer he delayed its implementation with the twin instruments of the Regional Councils Act and the Reasonable Use of Tamil Act, the weaker became the enthusiasm of the Sinhalese as well as of the Tamils.

The voices of the critics of the B-C Pact seemed to increase in volume and effectiveness as time went by. At the height of the tar-brush campaign it became evident that even within the Government Party there was a wide divergence of opinion about the efficacy of the major miracle of Mr. Bandaranaike’s Magic Wand – the B-C Pact. Even his own kin and henchmen muttered together in the dark corridors of Sravasti about how unpopular the Lokka (the Boss) was becoming in the country by persisting in his defence of the Pact. No one dared to approach him-it was hard to endure the whip-crack of the Lokka’s pliant tongue. Till the last moment he spoke in eulogies about the wondrous nature of the B-C Pact, of communal harmony, of brotherhood and of national unity. But no one had yet seen the Bills which for a whole year were being fabricated by the Legal Draughtsmen. And no one was impressed.

The Abrogation of a Pact

On the morning of April 9 (1957) a police message reached Mr Bandaranaike warning him that about 200 bhikkus or monks and 300 others were setting out on a visitation to the Prime Minister’s residence in Rosmead Place to demand the abrogation of the Pact. They would arrive at 9 a.m.

The Prime Minister left the house early that morning to attend to some very important work in his office. The bhikkus came, the crowds gathered, the gates of the Bandaranaike Walawwa were closed against them and armed police were hurriedly summoned to throw a barbed-wire cordon to keep the uninvited guests out. The bhikkus decided to bivouac on the street. Pedlars, cool-drink carts, betel sellers and even bangle merchants pitched their stalls hard by. Dhana was brought to the bhikkus at the appointed hour for food.

In the meantime, the Prime Minister was fighting off the opposition to the Pact among his own party colleagues with desperate fury.

At 4.15 p.m. the B-C Pact was torn into pathetic shreds by its principal author who now claimed that its implementation had been rendered impossible by the activities of the Federalists.

The Prime Minister had gone home that afternoon accompanied by half a dozen Ministers who stood on the leeward side of the barbed-wire barricade while Mr. Bandaranaike listened to the shrill denunciations of the monks. The Minister of Health sat on the Street facing the monks and preached a sermon, promising them redress if they would only be patient. The Prime Minister consulted his colleagues. The monks had won. The Magic Pact was no more.

But the monks insisted on getting this promise in writing. The Prime Minister went into the house and the Health Minister, hardly able to suppress the look of relief on her face, brought the written pledge out to the monks.

Yet another victory for Direct Action had been chalked up.”

****

from the Preface – “The people of Ceylon have seen how the mutual respect and good will which existed between two races for several hundred years was destroyed within the relatively brief period of thirty months. This book, most of which was written during those long, tense curfew nights of May and June 1958, is a record of the events, passions and under-currents which led to the recent communal crisis, and of the more remarkable instances of man’s inhumanity to man in those hate-filled days. It is also an account of the rapid disintegration of the old-established order of social and economic relationships in so far as it contributed towards the disaster which overtook the country… Many Ceylonese-Sinhalese and Tamils-lost their lives in the riots of May and June. Many of them lost their children, their property, their means of livelihood and some even their reason. In Colombo, Jaffna, Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa, Batticaloa, Eravur, Kurunegala and many other places where the two communities clashed the ugly scars will remain tender long after time has buried the physical signs of chaos. There is no sense in putting the blame on one community or the other. A race cannot be held responsible for the bestiality of some of its members… Emergency ’58 ends with a question: ‘Have we come to the parting of the ways?’ Many thoughtful people believe that we have. Others, more hopeful, feel that the bloodbath we have emerged from has purified the national spirit and given people a costly lesson in humility… The story of the race riots of 1958 is a story of violence, unreason, anger, jealousy, fear, cynicism, vengeance and many other states of heart and mind which the people of Ceylon experienced. I have presented it like that and, therefore, I will freely admit that Emergency ’58 is opinionated. But I make one claim for the book: it has been written with the old journalistic saw in mind :facts are sacred, comment is free…”