by Tamil Guardian, London, July 2, 2025

Krishanthi Kumaraswamy was an 18-year-old Tamil schoolgirl from Jaffna whose brutal rape and murder in 1996, along with the killing of her mother, younger brother, and a neighbour, became one of the most notorious atrocities of Sri Lanka’s genocide of Tamils.

Her case exposed a grisly network of mass graves in Chemmani, symbolizing the broader pattern of violence and impunity faced by Tamils. Nearly three decades later, Krishanthi’s story endures as a stark emblem of the Tamil nation’s unresolved quest for justice.

Background

In 1995, the Sri Lankan military had invaded Jaffna displacing over half a million Tamil men, women, and children. The peninsula was under heavy military occupation. Widespread enforced disappearances were reported during this period – over 600 Tamil civilians went missing in 1995-96 alone – creating an atmosphere of fear. It was against this turbulent backdrop that Krishanthi, an ambitious student at Chundikuli Girls’ College, prepared for her G.C.E. Advanced Level examinations.

Tamils being displaced by the Sri Lankan invasion of Jaffna, 1995

On September 7, 1996, the 18-year-old cycled to school in her white uniform and red tie, to sit an exam, passing through an Army checkpoint at Kaithady on the Jaffna-Kandy road. That afternoon, after finishing her chemistry paper, Krishanthi headed home the same way – unaware of the fate that awaited her at the checkpoint.

Abduction, rape, and murder

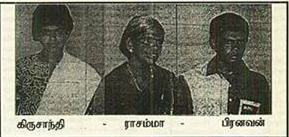

When she failed to return home, Krishanthi’s mother, Rasammah (Rajamma) Kumaraswamy, grew alarmed. Rasammah, 59, gathered Krishanthi’s 16-year-old brother Pranavan and a neighbor, 35-year-old Sithamparam “Kirupa” Kirupamoorthy, and rushed to the checkpoint to inquire about the schoolgirl’s whereabouts.

Rasammah was a former Principal of Kaithadi Muthukumaraswamy Maha Vidyalaya and was teaching at Kaithadi Maha Vidyalaya at the time of her murder. Pranavan was a bright student and studying at St. John’s College, Jaffna. Kirupa was a close friend of the family, who was working at the Co-operative Stores, and happy to help them find Krishanthi.

All four would be murdered.

Kirupa, Rasammah and Pranavan

The sheer brutality of the crime, sent shockwaves throughout the island. It was clear to the Tamil people that the crime was part of a broader pattern of violence under military occupation. Public protests erupted in Jaffna, forcing authorities to take the rare step of arresting security personnel for abuses against Tamil civilians. By October 1996, police had taken at least 7 suspects into custody (including army officers and two policemen implicated in disposing of the bodies). What began as yet another “disappearance” had now become an internationally noted case, which for the first time forced a spotlight on the conduct of Sri Lankan forces in the Tamil homeland.

Trial and convictions

In an unprecedented move at the time, the Sri Lankan government convened a Trial-at-Bar, a special high court with three judges, to hear the Krishanthi Kumaraswamy case. The trial began on November 18, 1996 in Colombo, far from the crime scene. Nine defendants were eventually indicted: six soldiers (including Rajapaksa and others directly involved in the assaults) and three Sri Lanka policemen who colluded in the cover-up. Notably, two low-level policemen (including Abdul Hameed Nazar) agreed to turn state witnesses and received conditional immunity for their cooperation.

Over the course of nearly two years, the court heard harrowing evidence from dozens of witnesses, including a fellow soldier who had initially been detained as a suspect, and the two policemen-turned-witnesses who described how the captives were handled.

Eventually, however, the full heinous nature of the crime was laid bare.

As Krishanthi reached the occupying military checkpoint in Kaithady, the soldiers on duty stopped her. Lance Corporal Somaratne Rajapaksa, had her taken into a bunker, and tied a piece of cloth around her mouth.

Prashanthi Mahindaratne, state counsel in the landmark case who was later appointed as a trial attorney at the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, The Hague, gave in interview in 2017 that described the details of what happened in Krishanthi’s last moments.

“First, she resisted and struggled and then it became obvious to her that there was no way that she was going to get out. She realized that she would be killed.”

“What has come to my mind from all of this is Krishanthi’s last moments, which was divulged from the consistent confessions made by the soldiers. Nobody was fabricating.”

“When Krishanthi had been raped by about five men she reached a point when she gave up. When the sixth approached her, she knew for a fact that she was going to be raped again. But she didn’t resist any longer. Instead she just said, ‘Please give me a moment. Let me have some water.’”

“She was raped behind the bunker, in an open area. Then they brought a rope, strangled her and buried her behind the checkpoint in a marshy land. The body was naked but her clothes were put into the same pit.”

According to later court testimony, Krishanthi was gang-raped by nine Sri Lankan soldiers and then murdered – strangled and buried in a shallow pit.

“Thereafter, her mother, brother and the neighbour came to the checkpoint in search of the girl.”

At first, the soldiers denied detaining Krishanthi. Rajapaksa even pretended to radio others as if to confirm she wasn’t there. Unconvinced, Rasammah insisted on staying until her daughter was found. Sensing trouble, the patrolmen refused to let the family leave; Rajapaksa barked, “You can’t come here any time you want and leave anytime you want,” effectively taking the three searching relatives into custody as well. By evening, the Army’s crime had compounded horrifically.

Her young brother and the male neighbour were also savagely killed, both of them strangled to death.

Their bodies were dumped in a hastily dug grave, as was that of Rasammah.

Five days later, in mid-September 1996, the bodies of all four victims were uncovered from shallow graves in the Chemmani area of Jaffna.

Mahindaratne says:

“They detained the three people also, strangled and killed them and buried them in the same marshy land. There were four separate pits but in the same marshy land. In the course of confessions, it came out that the three civilians had also realized they were going to be killed and had given up, because the mother had taken off her thali (gold necklace worn after marriage) and all three had handed over their identity cards, in an act of surrender.”

In July 1998, six of the perpetrators all military servicemen were convicted for their roles in the gang-rape and killings. One accused died during the trial and one was acquitted.

No other soldiers or officials were investigated or held accountable, despite evidence of more senior involvement.

As the International Commission of Jurists would later note,

“Rather than being emblematic of judicial integrity, this rare instance of a high-profile successful prosecution appears to have been the exception that proved the rule of impunity.”

The courtroom victory only scratched the surface of a much larger tragedy that was about to unfold, led by revelations from one of the convicted killers himself.

Chemmani mass graves exposed

Rajapaksa, under heavy security, guides officials to a mass grave site in Chemmani, 1999

At the very end of the trial in 1998, as his guilty verdict was delivered, Lance Corporal Somaratne Rajapaksa made a stunning disclosure to the court. Insisting that he was not the actual murderer (despite eyewitnesses to the contrary), Rajapaksa claimed that “we did not kill anyone – we only buried bodies”, and that hundreds of corpses of slain Tamils were secretly buried by the Army in the Chemmani area.

In a statement from the dock, he alleged that “300 to 400 bodies” lay in mass graves near Chemmani and offered to identify the sites if investigators took him there. It corroborated what many families had suspected about their disappeared loved ones. Chemmani became synonymous not only with Krishanthi’s case, but with one of the largest mass grave scandals in the island’s history.

Under mounting domestic and international pressure, the government belatedly organized an inquiry in 1999 (after months of delays and apparent foot-dragging). In June 1999, Rajapaksa was flown under tight security to Jaffna, where a magistrate from outside the region was appointed to supervise excavations. Over subsequent weeks, the grim task of unearthing Chemmani’s secrets began. Acting on information from Rajapaksa and other convicts, forensic teams exhumed at least 15 skeletal remains from several shallow graves in the Chemmani marshes and fields. Disturbingly, many of the skeletons unearthed were found blindfolded with hands bound, clear evidence that the victims had been executed and buried en masse. Two of the recovered skeletons were later identified as the remains of local Jaffna men who had “disappeared” in military custody in August 1996, lending credence to Rajapaksa’s testimony that the site held civilians arrested and killed by the Army. International observers, including experts from Physicians for Human Rights (USA), were present to monitor the exhumations.

These discoveries confirmed Chemmani as a killing field. The case of Krishanthi had pulled back the curtain on a much wider campaign of disappearances and extrajudicial killings in Jaffna around 1996. The Chemmani mass graves became a byword for Sri Lanka’s genocide. Locals recalled that during that time, bodies often turned up by roadsides or in shallow pits, only to be hurriedly disposed of. Rajapaksa’s detailed court confession described how entire groups of detainees, ranging from 25 to 50 at a time, were tortured and killed under orders from superior officers, and how he and others were instructed simply to bury the corpses. He even implicated high-ranking officers by name (including a Jaffna Sector commander and several captains and lieutenants) in the arrests, torture, rape, and murder of Tamil civilians.

Death threats on death row

For the first time, a serving soldier’s testimony directly linked the Sri Lankan Army’s top brass to heinous crimes – a fact that deeply unsettled the military establishment. In the lead-up to the Chemmani excavations, Rajapaksa faced intense intimidation: he was beaten by prison guards in August 1998 for refusing to recant his statement, and his family received anonymous death threats warning that if he pointed out graves, his wife and children “will be murdered”.

However, after those initial discoveries, the momentum for justice in the Chemmani mass grave investigation stalled. The Sri Lankan Ministry of Defence opened an inquiry, but it soon faltered amid government indifference and perhaps deliberate obstruction. Only 15 bodies were exhumed, far fewer than the hundreds alleged. By 2000, authorities took the half-hearted step of inviting families of missing persons to come inspect clothing and personal effects found with the remains, in hopes of identifying more victims. And yet, no further prosecutions followed.

The 1999 excavation

The Attorney General’s department did gather DNA samples from some families, but bureaucratic delays and lack of political will meant no one was ever charged for the Chemmani mass killings beyond the original Krishanthi case perpetrators. A U.S. State Department report in 2004 noted that the case had languished with “no significant progress”. The gruesome evidence unearthed in Chemmani was effectively swept under the rug; to date, no senior officer has faced trial for ordering those murders, and the full scope of the Chemmani graves remains unresolved.

Aftermath and Legacy

In 2003, six death-row convicts from the case appealed their sentences, but the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka upheld their convictions in 2004, affirming the verdicts

It is widely perceived that the higher-ranking architects of the Chemmani crimes – the officers who gave orders and the officials who covered it up – were shielded from accountability. In a disturbing footnote, in 2007 a Jaffna social worker named S.T. Gnanamuthu (Gananathan), who had helped expose Krishanthi’s case and advocated for victims’ families, was assassinated by unknown gunmen near an army camp. Locals believed it was a revenge killing by those who resented the convictions; his murder reinforced fears that elements of the security forces were still willing to eliminate witnesses and activists even a decade later. Such episodes compounded the trauma of Krishanthi’s family (the surviving relatives) and the broader community.

Today, Krishanthi Kumaraswamy’s memory lives on as a symbol of both justice and its limits. Every year, Tamil civil society groups and relatives of victims gather to remember Krishanthi and the Chemmani massacre. A memorial stands in Chemmani to honour her and the others who died on that day. In Jaffna, an annual memorial event on September 7th marks the anniversary of her death, with community leaders lighting oil lamps and family members speaking of their loss, ensuring that Krishanthi is not forgotten.

A tribute held to Krishanthi in 2017

In early 2025, the Chemmani area again made headlines when new skeletal remains were accidentally unearthed during construction at a local cremation ground – sparking fresh investigations and reopening old wounds. Thus, nearly 29 years later, the ground in Chemmani is still yielding dark secrets. For the Tamil people, the fate of Krishanthi Kumaraswamy and the discovery of the Chemmani mass graves remain a chilling reminder of the atrocities committed during the war and the long road to truth and justice.

Her story poses an unresolved question: How many more Krishanthis lie buried, and will their killers ever face justice?

Excavations at Chemmani earlier this year