by Anwar Halari, The Conversation, Boston, USA, July 29, 2024

We live in a world dominated by colossal corporations. The likes of Microsoft and Apple are bigger than most economies. Not long ago, however, a British company dwarfed these giants, yet few people know its history or the valuable lessons it can teach us today.

I am talking about the East India Company (EIC), an unrelenting force in world affairs from 1600 until as recently as the 1870s. Its history and importance are perfectly summed up by the Scottish historian William Dalrymple in his 2019 book, The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company.

I read it last Christmas and could barely put it down. It spoke both to my south Asian roots and my accountancy specialism, since the company’s first governor, Sir Thomas Smythe (1558-1625), was an auditor. Dalrymple, who has lived most of his life in India, meticulously explains how this one company became the de facto ruler of the subcontinent for more than a century.

Welcome to our new series on key titles that have helped shape business and the economy – as suggested by Conversation writers. We have avoided the Marxes and Smiths, since you’ll know plenty about them already. The series covers everything from demographics to cutting-edge tech, so stand by for some ideal holiday reading.

The East India Company was set up as a “joint stock” company, meaning it was controlled by its investors. And it wasn’t just elite figures like the mayor of London who held stakes, but British people from every walk of life – from sandal makers to leather workers to wine merchants.

This model meant access to essentially unlimited finance, since more investors could always be found. They were attracted by the company’s official charter from Queen Elizabeth in 1600, which gave it an exclusive trading monopoly over India.

The company gradually grew in military might and was able to exploit the chaos and instability caused by the decline of the Mughal empire, which had ruled large parts of the subcontinent until the early 18th century (this is “the anarchy” Dalrymple refers to in the title).

His book details the greed and arrogance of important company figures such as Lord Robert Clive (1725-1774), who became the first British governor of Bengal, and Warren Hastings (1732-1818), the first governor-general of India. Clive is described as a “violent, utterly ruthless and intermittently mentally unstable corporate predator”, though also an “extremely capable leader of the company and its military force in India”.

Robert Clive c.1764 by Thomas Gainsborough. National Army Museum

A pivotal moment came under his leadership in 1757, when he defeated the Bengali leader (the nawab) and his French allies at the Battle of Plassey. Dalrymple recounts how Clive personally entered the treasury of the nawab in the city of Murshidabad, and ended up taking most of it for himself. He “returned to Britain with a personal fortune then valued at £234,000” (£35 million in today’s money).

From Bengal, the East India Company came to exert control over large parts of the subcontinent, with numerous battles, massacres and atrocities along the way. Yet this victory in Bengal also ironically led to one of its biggest crises: the value of the stock had doubled on news of the company’s success, but then collapsed in 1769 after it had become overextended militarily and commercially, and faced a famine in Bengal.

Dalrymple describes how company tax collectors were ruthless during this famine, brutally enforcing high taxes in what was euphemistically described as “shaking the pagoda tree”. These would have been major human rights violations today, but weren’t enough to prevent a cash crunch in which the company was unable to pay creditors or taxes.

By this stage, the company was responsible for a staggering 50% of global trade. In 1773, it became the original institution deemed “too big to fail” as the British government stepped in with “one of history’s first mega-bailouts”.

The company paid with some restrictions in its autonomy, but remained extremely powerful for years to come. Its private army peaked at around 250,000 men in the early 19th century, bigger than that of the British army (Dalrymple likens it to Walmart having its own fleet of nuclear submarines). Thus, the colonial takeover of India was achieved not by state power but corporate strategy, backed by private military force.

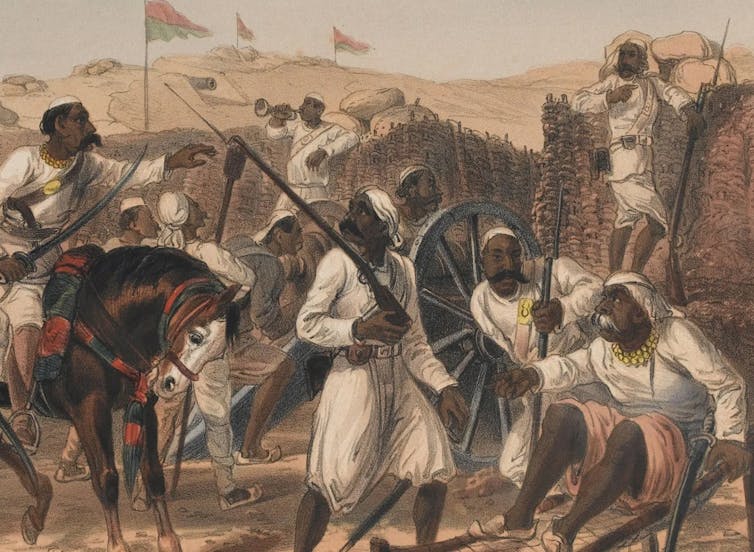

Mutinous Sepoys, 1857 (William Simpson, E. Walker and others after G.F. Atkinson, 1857-58) National Army Museum

It must have seemed like the company would continue indefinitely – but growing criticism of its tough trading tactics and corruption led to successive efforts by the British government to limit its power. The final straw was the mutiny of 1857, which started among Indian soldiers in the EIC army and spread across the subcontinent.

After it was put down by the British, with some 100,000 Indians killed, the government assumed direct control of India. So began the era of the British Raj. The EIC military was absorbed by the Crown and within a few years, the company was dissolved.

Moral lessons

For me, the most important takeaway from The Anarchy is summed up by a quote from one of its cast of characters, the 18th-century Tory politician and lord chancellor, Baron Edward Thurlow:

Corporations have neither bodies to be punished, nor souls to be condemned; they therefore do as they like.

East India ship Repulse, 1820, by Charles Henry Seaforth. Wikimedia

Dalrymple vividly describes how we can still see the results today in Powis castle in central Wales, of all places. It is “awash with loot from India, room after room of imperial plunder, extracted by the East India Company … there are more Mughal artefacts stacked in this private house in the Welsh countryside than are on display in any one place in India – even the National Museum in Delhi”.

The Anarchy reminds us that the most profitable and innovative businesses can become vessels for exploitation without appropriate accountability and governance. The book is on its way to becoming a modern classic for its analysis of this decay.

Today’s massive corporations lack the company’s military strength, and corporate governance has thankfully improved over the last couple of centuries. Yet these entities are still incredibly powerful. Among the world’s top 100 economic operators, almost 70% are corporations.

The biggest companies are set to dominate new technologies like AI, which will make them seem even more unassailable. The demise of the British East India Company at least reminds us that governments ultimately have the power to reassert themselves, if the will is there. Through all the corporate brutality and corruption on display, The Anarchy does carry that message of hope.

***

The Anarchy by William Dalrymple review – the East India Company and corporate excess

Patriotic myths are exploded in a vivid pageturner, which considers the Company as a forerunner of modern multinationals, ‘too big to fail’

From the hindsight of the 1920s, this embassy looked like a key step in the building of a British imperium that would end with Britain’s monarchs as India’s emperors. But the arrival of the British in India in the early 1600s looked very different at the time – and from the other side. A contemporary painting by the Mughal master miniaturist Bichitr shows a supersized Jahangir on his throne, bathed in a halo of blinding magnificence. He hands a Qur’an to a white-bearded Sufi, a pious gesture that doubles as a majestic snub: pressed into a lower corner is none other than James I, an overlooked supplicant, depicted in three-quarter profile, “an angle reserved in Mughal miniatures for the minor characters”.

The difference between these two images is the distance travelled by William Dalrymple’s The Anarchy, a graphic retelling of the East India Company’s “relentless rise” from provincial trading company to the pre-eminent military and political power in all of India. The company’s transition from trade to conquest has preoccupied historians ever since Edmund Burke famously attacked it as a “state in the disguise of a merchant”. Building on foundational research by CA Bayly, KN Chaudhuri and PJ Marshall among others, a new cohort of scholars writing in the wake of the financial crisis (Emily Erikson, Rupali Mishra, Philip Stern, James Vaughn) have studied the company as a forerunner of modern multinationals, intertwined with the modern state and “too big to fail”.

Dalrymple’s first achievement in The Anarchy is to render this history an energetic pageturner that marches from the counting house on to the battlefield, exploding patriotic myths along the way. Thus Robert Clive, once celebrated as “Clive of India”, enters here as a juvenile delinquent from Shropshire who arrived in Madras in 1744 as an 18-year-old clerk, but found his vocation as a thuggish fighter in the company’s small security force.

Miniature of Jahangir, with James I in white, below. Photograph: The Picture Art Collection/Alamy

As to the Battle of Plassey of 1757, which won the company control of Bengal and which generations of British schoolchildren would memorise as a glorious imperial victory, the real story was substantially more complicated. The volatile, widely disliked Nawab of Bengal, Siraj ud-Daula, had made an intractable enemy of Bengal’s Marwari bankers, the Jagat Seths, who saw better prospects in investing with the East India Company than supporting him. The Jagat Seths offered the company more than £4m (about a hundred times that in current terms, reckons Dalrymple) to unseat Siraj ud-Daula and install a compliant collaborator in his stead. Clive, who stood to make an immense personal fortune, gladly accepted. Plassey was in truth a “palace coup”, executed by a greedy opportunist, won by bribery and betrayal.

It took six months in those days for news to travel from Calcutta to London, and even when it arrived, few really understood what was going on in Bengal. “Was it true,” asked one company director, that “Sir Roger Daulat” was a baronet? What the directors did understand they did not much like, since taking on territory meant taking on risk and expense. Meanwhile a snobbish disdain for the extravagance of the “nabobs” (Clive foremost), and fear about their corrupting influence on British politics, led to a Regulating Act designed to bring the company under tighter parliamentary control. The man picked to run a cleaner administration was the “plain-living, scholarly, diligent and austerely workaholic” Warren Hastings, who spoke several South Asian languages, had a “deep affection for India and Indians”, and sponsored serious scholarship on Indian culture. But Hastings’s “rule was as extractive as ever”, and his ruthless tactics towards the company’s Indian subordinates got him spectacularly impeached in 1787. Governors-general after Hastings would be no less violent – just far more racist.

However well-known these events may be to some – thanks not least to his own work – Dalrymple’s spirited, detailed telling will be reason enough for many readers to devour The Anarchy. But his more novel and arguably greater achievement lies in the way he places the company’s rise in the turbulent political landscape of late Mughal India. It was contemporary Indian chroniclers who called this period “the anarchy”, due to the waves of invasion and civil war that shook Mughal power and allowed a host of regional actors – of which the company was merely one – to gain ascendancy.

Dalrymple brings the insights of years of living in Delhi and immersing himself in Indian art, archives and historical sites. He draws on reams of scarcely used documents in Persian, Urdu and other languages (unearthed by skilled researchers and translators) to animate characters such as the brilliant Mughal general Najaf Khan, the vengeful Rohilla prince Ghulam Qadir, and the canny Maratha statesman Mahadji Scindia. He has a particular talent for using Indian paintings as historical sources, a skill complemented by the volume’s sumptuous illustrations. And nobody sets a scene as well as he does, whether scoping out an enemy fleetthrough an informant’s spyglass, or watching the waterlogged bodies of famine victims floating down the Hooghly river, or roaming the rubbished and ruined streets of ransacked Delhi.

Miniature of Lord Clive of India. Photograph: The National Trust Photolibrary/Alamy

Underscoring the centrality of Indian actors to this history, he ends The Anarchy not with a bureaucratic milestone, such as the company’s loss of its monopoly in India in 1813, but with a highly symbolic one: its conquest of Delhi in 1803. “We are now complete masters of India,” declared a general. The emperor Shah Alam, the tragic hero in a book rife with villains – a figure who had witnessed the Persians sack Delhi, battled against Clive, survived an assassination plot, the rape of his family, and a hideous blinding – would live out his remaining few years as a pensioner in the Red Fort, where he dictated “the first full-length novel in Delhi Urdu” about “a prince and princess tossed back and forth by powers beyond their control”.

Dalrymple steers his conclusion toward a resonant denunciation of corporate rapacity and the governments that enable it. This story needs to be told, he writes, because imperialism persists, yet “it is not obviously apparent how a nation state can adequately protect itself and its citizens from corporate excess”. And it needs to be read to beat back the wilfully ignorant imperial nostalgia gaining ground in Britain and the poisonously distorted histories trafficked by Hindu nationalists in India. It needs to be read because with constitutional norms under threat in both countries, the defences seem more fragile than ever.