Book Review

by Sachi Sri Kantha, August 21, 2024

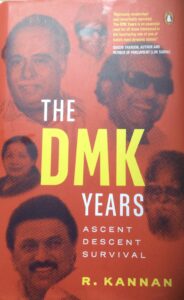

The DMK Years – Ascent, Descent, Survival by R. Kannan, Penguin Random House India, Gurugram, Haryana, 2024, 748 pp, 1,299 rupees.

Year 2024 marks the 75th birth anniversary year of Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) party of Tamil Nadu AND the birth centenary year of Muthuvel Karunanidhi (hereafter MK) – the long-time leader of DMK from 1969 to 2018. Rajarathinam Kannan, the author of this tome, had previously published two biographies in English on C.N. Annadurai (Anna, 1909-1969), the founder leader of DMK and M.G. Ramachandran (MGR, 1917-1987), the founder leader of DMK’s offshoot Anna DMK, in 2010 and 2017 respectively. This third work by Kannan, completing the trilogy of recording the DMK story until 2024 – is a stupendous effort by a dedicated student of law and Tamil Nadu politics.

Year 2024 marks the 75th birth anniversary year of Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) party of Tamil Nadu AND the birth centenary year of Muthuvel Karunanidhi (hereafter MK) – the long-time leader of DMK from 1969 to 2018. Rajarathinam Kannan, the author of this tome, had previously published two biographies in English on C.N. Annadurai (Anna, 1909-1969), the founder leader of DMK and M.G. Ramachandran (MGR, 1917-1987), the founder leader of DMK’s offshoot Anna DMK, in 2010 and 2017 respectively. This third work by Kannan, completing the trilogy of recording the DMK story until 2024 – is a stupendous effort by a dedicated student of law and Tamil Nadu politics.

Though the book provides detailed coverage on the activities of Tamil Nadu’s leading politicians of the 2nd half of 20th century of all shades in chronological sequence, the hero of the book is MK, and his interactions with these prominent personalities of the state as well as those who held power in New Delhi, from Indira Gandhi’s period as the prime minister, since 1969. Please check the table in pdf below for a listing of primary rivals/foils in MK’s political career. The singular blunder of MK’s political career was his expelling of MGR, a pal of 25 years standing, from DMK in October 1972. Kannan opines this blunder as “By expelling MGR, Karunaninidhi had unwittingly forced the metamorphosis of the actor-politician to a political leader. MGR was no more his Puratchi Nadigar. He had catapulted him to Puratchi Thalaivar (Revolutionary Leader).” The ‘hyperbolic title Puratchi Nadigar (Revolutionary Actor) to MGR, was offered by MK himself in 1954 during the production of Malai Kallan movie in 1954.

Table – Karunanidhi’s rivals, foils in Political Life

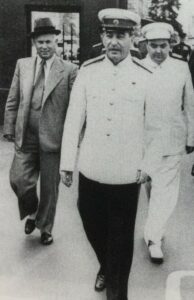

Two prominent Soviet era personalities were recognized in the early years of DMK history. First was none other than Josef Stalin (1879-1953). MK had unusually named his third son, born on March 1, 1953 (few days before the death of Soviet dictator), in honor of Stalin. Currently, he is the leader of DMK, following his father since 2018. Second was Gyorgyi Malenkov (1902-1988), who was Stalin’s Number 2, and held the leadership position for only ten days following Stalin’s death, before being deposed by Nikita Khrushchev. DMK’s leader Anna, had brashly proclaimed alliteratively ‘Moscovitku selluvaen- Malenkovidam solluvaen’ [I’ll travel to Moscow and proclaim to Malenkov], about DMK being the true proponents of Communism in Tamil Nadu, and not the party which carried the name Communist Party of India. Anna’s proclamation turned out to be an empty boast. He neither travelled to Moscow nor met with Malenkov.

But, in adopting cinema as a propaganda medium for politics, DMK leadership did follow Stalin’s writ to the dot. As per the overview of Peter Kenez (The Oxford History of World Cinema, 1996, pp. 389-398), Stalin’s take on movie making was as follows: “According to official doctrine, it was the script writer, rather than the director, who was the crucial figure and ultimately responsible. Stalin thought that the director was merely a technician whose only task was to position the camera, following instructions already in the script.” Then, David Robinson, in his ‘The History of World Cinema’ (1973) had noted, “ ‘The cinema’, said Stalin, the Commissar for Nationalities, ‘is the greatest medium of mass propaganda. We must take it in our hands.’ ” Sources are meagre on how much inspiration Joe Stalin offered to Anna and MK to focus primarily on cinema as the propaganda medium to exploit Tamil Nadu. However, DMK did follow Stalin’s writ on film making, by beginning with Anna’s ‘Velaikkari’ (1948) and ‘Sorgha Vasal’ (1954) as well as MK’s ‘Manthiri Kumari’ (1950), ‘Parasakthi’ (1952) and ‘Malai Kallan’ (1954).

But, in adopting cinema as a propaganda medium for politics, DMK leadership did follow Stalin’s writ to the dot. As per the overview of Peter Kenez (The Oxford History of World Cinema, 1996, pp. 389-398), Stalin’s take on movie making was as follows: “According to official doctrine, it was the script writer, rather than the director, who was the crucial figure and ultimately responsible. Stalin thought that the director was merely a technician whose only task was to position the camera, following instructions already in the script.” Then, David Robinson, in his ‘The History of World Cinema’ (1973) had noted, “ ‘The cinema’, said Stalin, the Commissar for Nationalities, ‘is the greatest medium of mass propaganda. We must take it in our hands.’ ” Sources are meagre on how much inspiration Joe Stalin offered to Anna and MK to focus primarily on cinema as the propaganda medium to exploit Tamil Nadu. However, DMK did follow Stalin’s writ on film making, by beginning with Anna’s ‘Velaikkari’ (1948) and ‘Sorgha Vasal’ (1954) as well as MK’s ‘Manthiri Kumari’ (1950), ‘Parasakthi’ (1952) and ‘Malai Kallan’ (1954).

During the 1950s Cold War environment, the vociferous claims of DMK leaders that they represent the ‘true’ Communists did attract the attention of American political establishment. A pioneer study by American academics Lloyd Rudolph (then an assistant professor of Government, Harvard University) and his wife Susanne Hoeber Rudolph, who were in Madras in 1957 was funded by a Ford Foundation grant (later to be identified as a philanthropy arm of CIA). This study by Rudolph was published in the Journal of Asian Studies, May 1961. Rudolph concluded his study with the inference, “The DMK appeals very little to women, a result which may very well be associated with its ‘atheist’ reputation, while the Communists attract neither conspicuously more nor less than other parties. While, on the whole, both parties appeal to approximately the same occupational groups in roughly the same proportions as other parties, the retailers drop off sharply in the Communist Party, while they see the DMK as no threat. Unskilled laborers constitute a large proportion of DMK voters than of any other party.”

Lt to Rt – Nikita Khrushchev, Joe Stalin and Gyorgyi Malenkov in Moscow, 1945

This inference by Rudolph explains the immense contribution of MGR (who had joined the party in 1953) to the DMK’s vote bank, by his espousal of ‘respect to the Thai kulam (Mother tribe), in his numerous movies of that period. For MGR, the word ‘Thai’ (mother) was a talisman and once he became the leading star, he insisted in tagging the ‘Thai’ word to his movies beginning from 1956 (Thaiku Pin Thaaram/ Wife after the Mother). This trend came to an end with Thaiku Thalai Magan/ Eldest son of the Mother, only weeks before DMK captured the majority in 1967 Legislative Assembly elections.

Decadal population increase in Tamil Nadu reflects the fortunes of DMK’s ascent, descent and survival. During its ascent years, in 1951, 1961 and 1971, the population of Tamil Nadu was 30.119 million, 33.686 million and 41.199 million respectively. During the ascent period of DMK of 1950s, implementation of rural electrification scheme promoted by the regime of Congress Chief Minister K. Kamaraj (1903-1975) aided in spreading DMK’s message via cinema theaters newly mushrooming in rural areas of Tamil Nadu.

MK’s influence was at its peak as the elected chief minister during the 1971 election to the Tamil Nadu state assembly and the Lok Sabha elections. The following year, he expelled MGR from the party, and the descent phase began. In 1981, when MGR was in his 2nd term as the chief minister, the Tamil Nadu population was 48.408 million. Following MGR’s death in December 1987, MK was able to reclaim the chief ministership in 1989, only to be beaten by MGR’s protégé Jayalalitha in 1991. Tamil Nadu’s population had grown to 55.858 million. From 1991 till Jayalalitha’s death in December 2016, MK had to tussle with her for supremacy and he failed to win two general elections consecutively, with all the permutations and combinations of alliances with other minor parties. Eventually when MK had to quit the chief minister position after losing the popular election to Jayalalitha in 2011, Tamil Nadu population had expanded to 72.147 million.

The survival phase of DMK, began when MK had to reluctantly hand over the run of the mill operations of the party to his son Stalin, in preference to his other ruffian son Alagiri, two years senior to Stalin. With age-related debilitations, MK held on to the hope of dying in harness as the chief minister of Tamil Nadu, like his mentor Anna (in 1969) and his political rival MGR (1987). But, he was cheated of this outcome. In this MK was less blessed than her junior rival Jayalalitha, as well.

Kannan’s book has two merits. First, exhaustive minutiae on details of DMK activity in Tamil Nadu and in the corridors of power in New Delhi (from 1971 onwards) is provided in 31 chapters, supplemented by three appendices – synopsis of parliamentary elections 1952-2019, Tamil Nadu State Assembly elections 1952-2021 and Manifesto highlights of DMK, Congress and Anna DMK parties. Secondly, as of now, providing a complete listing (with a couple of exceptions) of how DMK played up the Eelam Tamil issue from 1977 to May 2019, MK’s vanity flip flops and how he lost the status of most admirable Tamil leader status to MGR, from 1983. Though the book offers readers a feast, chapter by chapter, of what MK and his associates did on which date and where, in many occasions it fails to answer the vital question ‘why’ he did it. In my view, MK’s actions can be answered simply in a sentence – he was the unchallenged Indian master of realpolitik. The dictionary defines the word ‘realpolitik’ as “n. politics based on realities and material needs, rather than on morals or ideals.”

The primary contribution of DMK and that of MK to the Tamil Nadu politics was not to allow the Communist Parties to gain a foot hold in the Tamil Nadu soil, whereas the Communists thrived in the neighboring Kerala state. MK achieved this goal by his multi-tasked, disciplined routine in the 1950s – by being a superb orator, playwright, poet, Tamil movie script writer, movie production company owner, journalist and electorally successful politician. Writers with Communist sympathies like D. Jayakanthan also dabbled in Tamil movies had a tough time competing with MK in this turf battle.

MK was also extremely prolific, which tells something about his commendable time management skills, while sharing his life with two wives (Dayalu and Rajathi) from 1968. He heaped in quantities, as presented by Kannan at the end of the book – six volumes of autobiography, 54 volumes of Letters to his Followers in DMK’s mouthpiece Murasoli daily paper, and 12 volumes of speeches at the Legislative assemblies. This is an incomplete count of MK’s productivity. Over 50 Tamil film scripts of MK cannot be excluded. But, how about the quality of MK’s writings?

DMK Promotional songs

I don’t have an appropriate measuring scale in comparing MK to his talented contemporaries. Nevertheless, I include one. In a selection endorsed by European scholars of Tamil literature (professors Ronald E. Asher and Kamil Zvelabil) in 1974 for the 2nd volume of Dictionary of Oriental Literature (South & South East Asia), as a Tamil literatus, MK fails to get ranked among his thirteen contemporaries, who made the listing. These thirteen contemporaries (in alphabetical order) were, C.A. Annadurai (aka Anna, 1909-69), C.S. Cellappa (1912-1998), Kanaka Suppurathinam (aka Bharatidasan, 1891-1964), T. Janakiraman (1921-1982, D. Jayakanthan (1934-2015), R. Krishnamurty (aka, Kalki, 1899-1954), C. Mani (aka Palanisamy, 193-2009), Pudhumaipithan (aka Viruthachalam, 1906-1948), C. Rajagopalachari (aka Rajaji, 1878-1972), L.S. Ramamirtham (1915-2007), S. Vaidheeswaran (b. 1935), Mu Varadarjan (aka Mu Va, 1912-1974) and T.S. Venugopalan (b. 1929).

Among the mentioned 13 literati, MK’s mentor Anna, Bharathidasan, D. Jayakanthan were involved in Tamil movie industry. Due to its own blind spots, one cannot tag this listing as the gold standard of top Tamil literati of the 20th century. To be fair by MK, his equally talented contemporary Kannadasan (192-1981) was also excluded in this listing, in preference to a lesser known poets C. Mani and S. Vaidheeswaran (a son-in-law of stage and movie actor S.V. Sahasranamam). Also, not a single Eelam Tamil literati of equal rank in the 20th century was included.

Occasionally, Kannan teases the readers by offering interesting tidbits on events, but withhold delivering the eventual result. For example, “Sampath contesting the South Madras parliamentary seat [in 1962] said he would beard the lion (the DMK) in its den. Anna smilingly admitted that it was fine to meet the lion, but as to who would exit the den – the lion or the visitor – was to be seen.” Did Sampath became a lion killer? Sadly, he was devoured by a young DMK ‘lion’ – Nanjil K. Manoharan. The result was: K. Manoharan (DMK) – 151,917 votes, C.R. Ramaswamy (Congress) – 89,771 votes, and E.V.K. Samapth (Tamil National Party) – 63,768 votes. With this victory over Sampath, Manoharan became a recognizable DMK leader.

In a tome like this, a few omissions are bound to happen. Kannan makes reference to the DMK promotional songs of Nagoor E. M. Hanifa (1925-2015) which were cut into gramophone records for repeated playing before a propaganda event. Two other distinguished names who contributed to this angle by solo songs were Chidambaram S. Jayaraman (1917-1995, MK’s brother in law) and S.C. Krishnan (1929-1983). Both were well known playback singers in Tamil movies of 1950s. For listening, I provide below Youtube links of five such songs by Jayaraman and Krishnan.

Anna enpathu oruvarai than – C.S. Jayaraman

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g-XczoGOZsc&list=PLviYSX9LX22ZErOaCKyqDNd3AC_PqEGxr&index=9

Kopathai maranthuvidu – C.S. Jayaraman

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qk8kAPUsdH0&list=PLviYSX9LX22ZErOaCKyqDNd3AC_PqEGxr&index=4

Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam – S.C. Krishnan

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i8zymH5mbJw&list=PLviYSX9LX22ZErOaCKyqDNd3AC_PqEGxr&index=5

Annavin thalamaiyile – S.C. Krishnan

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yatEcDQOQUk&list=PLviYSX9LX22ZErOaCKyqDNd3AC_PqEGxr&index=8

Thennakathin thiruvilakkam Arignar Anna – S,C. Krishnan

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eBy_k5RHk7M&list=PLviYSX9LX22ZErOaCKyqDNd3AC_PqEGxr&index=3

The book might have gained more focus, if few questions like the following were tackled by the author. First, why those who provided financial support the ascent of DMK in 1950s (those involved in the Tamil movie industry – K.R. Ramasamy, MGR, S.S. Rajendran, and even poet Kannadasan) had trouble dealing with MK, and all were either expelled or side-lined in intra-party intrigue. Secondly, though Muslims in Tamil Nadu form 5.5% of the population, how this constituency was handled by MK? I can note only two prominent Muslims (S.J. Sadiq Pasha and devotional singer Nagoor E.M. Hanifa) in the top ranks among DMK personalities. Thirdly, numerous caste groups, and their bargaining power are mentioned in the text – Vanniyar, Kongu Vellalar, Kallar, Pallar, Nadar, Thevar, Gounder, Adi Dravidas and last but not the least Brahmins. A table providing the caste-wise population percentages would have been of benefit for the uninitiated. Fourthly, the recurrent phenomenon of self-immolation by few DMK cadres reported in quite a number of pages, when MK was arrested or jailed appears to be a blight that promoted itself as a rationalist party. MK had devoted chapter 58 of his autobiography (vol.3, 1997), to these self-immolation cases, with the caption ‘Why self-immolation becomes a continuing story?’ and had provided details of few cases – Koviladi Brindavan, Perunthurai Muthu Pandian, Kallavi Rajendran, Tiruchi Manoharan, Tiruvaroor Kittu, Melmayil Jeganathan etc. Are these cadres psychiatric cases or were induced to take such drastic action for some other unexplainable reasons?

Kannan ends the book with the following thoughts: “Chief ministers and leaders who are not charismatic but caring, accessible and intelligent, who walk the earth like normal mortals and attend to work like any government servant, would be a welcome change. Colossuses no longer walk [in] Tamil Nadu. But is it too much of Tamils to ask that the high-minded and those seeking the public good again walk amidst them?”

For this to happen, second generation of MK family (currently led by Stalin) should study the past 40 years of history of Congress Party of India. Fourth generation of hereditary leadership in the post-Independent India (Nehru>Indira>Rajiv>Rahul) had depleted the needed vitality elements for re-emergence of the Congress Party at the national level. For the Congress Party, the rot started when a third generation guy was chosen to replace the assassinated mother Indira Gandhi. M.K. Stalin should seriously think about deviating from the precedence set by his father and let new faces to compete for the DMK leadership in the next decade, rather than anointing his son Udhayanithi as heir apparent.

Despite a few glitches noted above, Kannan had written a readable, splendid book on the political history of Tamil Nadu landscape of the last 75 years, from 1949.

The book is available at https://www.amazon.in/DMK-Years-Ascent-Descent-Survival/dp/0670097896

*****

What a refreshing perspective of the illustrious history of DMK party which mostly revolves around MK quiet deservingly, hats off to Mr. Kannan and reviewer Dr. Sachi.

It is a paradox that electrification of TN by Kamaraj led to mushrooming of movie theaters which enabled propaganda of DMK movie machinery which led to downfall of Congress in TN! I never thought of this paradox!

I am sure that Udhayanidhi will be the next CM despite the wishes of the author, Hereditary politics is so ingrained in the system in all south Asian countries.