http://www.sundaytimes.lk/140511/news/war-memorial-events-banned-in-north-98763.html

While the Government finalises plans to celebrate Victory Day in Matara next Sunday, Police and the military have warned that no public gatherings to remember persons killed in the final stages of the conflict will be allowed in the Northern Province. Special security arrangements would be put in place to monitor whether anyone is organising public events to remember the dead, but there would be no restrictions on family members to remember the dead within their house premises, Military spokesman Ruwan Wanigasuriya said.

He said that even two families would not be allowed to get together to have remembrances as these could turn into a large group and make it a commemoration. Meanwhile, Jaffna’s Senior Police Superintendent W.P. Wimalasena said police teams had been deployed in Jaffna to be alert to any move to hold public events to remember people killed in the final stages of the conflict.

“Any persons trying to hoist black flags, distribute leaflets or put up posters will be considered as supporting of terrorism and such persons will be taken into custody under the Prevention of Terrorism Act,” he warned. He said steps were being taken to prevent such remembrance events. The SSP said the authorities had closed the Jaffna University to prevent any remembrance events there.

The fifth anniversary of the defeat of the LTTE or Victory Day will be celebrated by the Government next Sunday in Matara with military parades and other events.

http://asiancorrespondent.com/122724/from-tiananmen-to-jaffna-banning-community-commemoration/

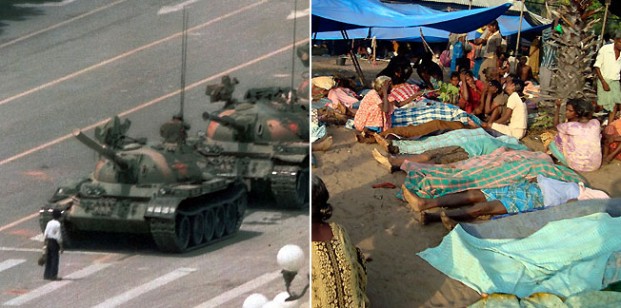

From Tiananmen to Jaffna: Banning community commemoration

By JS Tissainayagam, ‘Asian Correspondent,’ May 15, 2014

The parallels are stark. As the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre approaches, Chinese police have begun detaining activists who might be planning to stage protests against the government for the bloody killings that left hundreds dead and unleashed a wave of repression 25 years ago. Meanwhile, last week, Beijing’s dedicated acolyte, the Sri Lanka government, announced that anyone publicly mourning the dead in the country’s Tamil-dominated North, on the fifth anniversary of a slaughter which ended the military campaign, could be arrested for terrorism.

n May 6, the BBC reported that Pu Zhiqiang, an activist who had participated in the 1989 protests and tried to commemorate the tragic occasion every year was “likely to spend June 4 [date of the anniversary] in a police detention centre,” because he was arrested after attending a private meeting to discuss the event. The BBC said he “faced vague charges of ‘causing a disturbance.’” Six others, including a scholar and an Internet activist, are also in police detention, while five were arrested and released.

“We can definitely see the suspension of Pu Zhiqiang as a warning to civil society and to other lawyers ahead of June 4,” the BBC quoted William Nee, a researcher for Amnesty International, as saying.

On May 8, the BBC said that 70-year-old Gao Yu, a prominent dissident journalist had been detained, which her lawyer interpreted was to “set examples to whoever wants to hold events related to June 4”.

In Sri Lanka meanwhile, the government warned that no public events would be permitted in the Northern Province to mourn the dead on or around May 18. The day marks the official end of the country’s civil war in 2009 with the military defeat of the rebel Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). The final five months of fighting left between 40,000 and 70,000 dead – other estimates place the figure much higher – the majority of them Tamil civilians.

Sri Lanka’s Sunday Times newspaper said that the government issued a stern warning that while memorials could be held inside homes, no public events would be permitted. It reported Senior Superintendent of Police W. P. Wimalasena saying, “Any persons trying to hoist black flags, distribute leaflets, or put up posters, will be considered as supporting terrorism and such persons will be taken into custody under the Prevention of Terrorism Act.”

But that was not all. The story also quoted military spokesman Brigadier Ruwan Wanigasooria saying “[t]hat even two families would not be allowed to get together to have remembrances as these could turn into a large group and make it a commemoration.”

May 18 has come to symbolise different things in different parts of Sri Lanka. This precisely is the reason why the restrictions on mourning apply only to the Northern Province – the only Tamil-dominated province in the country. In areas outside the North, the government holds huge victory day celebrations, replete with militaristic symbols – marching columns, parading of military hardware and speeches reinforcing national unity and victory over terrorism and division of the country. These events have strong overtones of racism: the triumph of Sinhala nationalism, embodied by the government of President Mahinda Rajapakse and his family, over the Tamils by crushing their aspiration for dignity, rights and equality. This year’s event will be in Matara, on the southern coast.

The controversy over Tamils dedicating May 18 as a memorial for the dead is not new – it has gone on for five years. But what is of significance this year is that the government has not expressed its opposition to individual families mourning in private. It has banned families mourning collectively however – not only in public but in private too.

The distinction is all important. The government is not only worried about a public event becoming a show of protest and thereby undermining the ‘victory’ it wants to celebrate with the trappings of triumphalism. It is also anxious that it should not become an opportunity for collective, communal mourning.

The reason behind this is simple. Following a military victory, the victor imposes rules to ensure that the victim community remains with little social cohesion – broken, dispirited and at odds with itself. But acts of mourning, whether in private or public, help to restore communities fractured and atomised by the past (and ongoing) trauma. It is with this objective in view that let alone public memorialising, even group counselling and psychosocial projects for war-related trauma are discouraged by the Sri Lanka government in northern Sri Lanka.

Group therapy – even in a clinic – allows survivors to explore together their deepest feelings of suffering, trauma and guilt. It allows groups to understand common loss and devise inclusive strategies for overcoming them. But to Rajapakse and the military administration in northern Sri Lanka, any endeavour by Tamils to master their individual grief and recover as a community is unacceptable. Because that means what Colombo sees as the ‘enemy’ which was hitherto preoccupied by private and individual sorrow could use its collective power to effect other changes too, such as oppose oppressive political conditions.

The Rajapakse government finds anathematic any political action by the people other than what it is willing to champion or condone. But even in Sri Lanka where political freedom is minimal, a government found it difficult prevent people coming together for a public ceremony. Therefore it has adopted a new way – criminalising the reason for which people would come together.

By criminalising northern Tamils mourning their dead as an act of terrorism, which can be punished by arrest and detention under the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), Rajapakse hopes he can contain the Tamils’ moves to cohere as a community once again. And to bolster his strategy – and thereby justify a crackdown – the government has floated the story of the LTTE regrouping and the possibility of another armed uprising. Except for the government and its camp followers, nearly everyone else views the claims of a possible armed uprising with deep scepticism.

Rajapakse is well aware that the political conditions he has imposed on Sri Lanka by preventing accountability for war crimes and continuing human rights abuses have not created a ‘post-war’ environment at all. He realises that if people have any opportunity of coming together, the natural consequence would be to break out of the oppressive circumstances in which they find themselves.

In the final analysis, an autocratic government, whether run by the Communist Party in Beijing or by the Rajapakse family in Colombo, fears people with a political will that oppose its own. It is secondary whether the people use the ballot box, civil disobedience or armed combat to achieve their aim. What need to be nipped in the bud are people coming together as a community: therefore it is made a criminal act. As long as mourning facilitates the restoration of community, it will be opposed by oppressive governments. And as long as it is opposed – be it five years or 25 – the people will not give up trying to restore community either.

one photo from China.