by Thusiyan Nandakumar, Tamil Guardian, London, April 22, 2022

A monument to a man who oversaw two anti-Tamil pogroms and the architect behind one of the most racist pieces of legislation on the island’s history overlooks the Galle Face protests. If these protests are to be inclusive of all in Sri Lanka, that statue must go.

Just under two years ago, the US police killing of George Floyd reverberated around the world. In cities such as Bristol in the UK, protestors took to the streets. They marched to the city’s harbour and there, they toppled the statue of Edward Colston, a merchant and trans-Atlantic slave trader. It followed similar such moves across the world, from Canada and the USA to South Africa, where popular protests were removing monuments of men accused of racism and colonialism. Slave traders, genocidaires and US Confederate leaders were amongst them. These figures were being acknowledged as staining each country’s history rather than men that should be heralded. The removal of these monuments presented a willingness and opportunity to tackle the difficult issues that continued to plague each state, from genocide and race relations to the impact of colonialism.

In Sri Lanka, anti-government protests are currently surging across the south of the island. The island’s worst economic disaster in living memory has destroyed the livelihoods of millions, driven many into poverty and has led to multiple crises, from soaring food prices to an island-wide shortage of medicines in hospitals. At Galle Face in Colombo, protests have been ongoing for almost two weeks, with hundreds camping out in tents in front of the Presidential Secretariat, and crowds ebbing and flowing throughout the day. The demonstrators’ focal demand is clear – the resignation of Sri Lankan president Gotabaya Rajapaksa and the removal of this regime. Many protestors have gone further with their calls, proclaiming that this movement is the beginning of a ‘revolution’ for Sri Lanka. Some demands go deeper, from abolishing the system of the executive presidency, to justice for genocide and a complete restructuring of the state.

Whilst for Tamils there is wariness over whether any substantial developments will result from these protests, many in the South are more optimistic – pointing to the so-called “unity” that the demonstrations have, with participation from across ethnic and class lines. But as demonstrations continue in Colombo, there is one tangible act that the protestors can do to showcase their solidarity with the oppressed – topple the statue of SWRD Bandaranaike that overlooks their demonstration at Galle Face Green.

.jpg)

Bandaranaike was elected as Sri Lanka’s fourth prime minister on the back of pledges to introduce one of the most divisive and racist pieces of legislation in the island’s history – the 1956 Sinhala Only Act. The act has been singled out by many throughout the decades for fanning the flames of genocide and ethnic conflict on the island.

Oxford-educated Bandaranaike was an unashamed Sinhala nationalist who was acutely aware of the political capital to be gained from a ‘Sinhala Only’ policy. He once remarked to a journalist, “I have never found anything to excite the people in quite the way this language issue does”. As soon as he came to power, he passed the act enshrining Sinhala as the sole national language of the country.

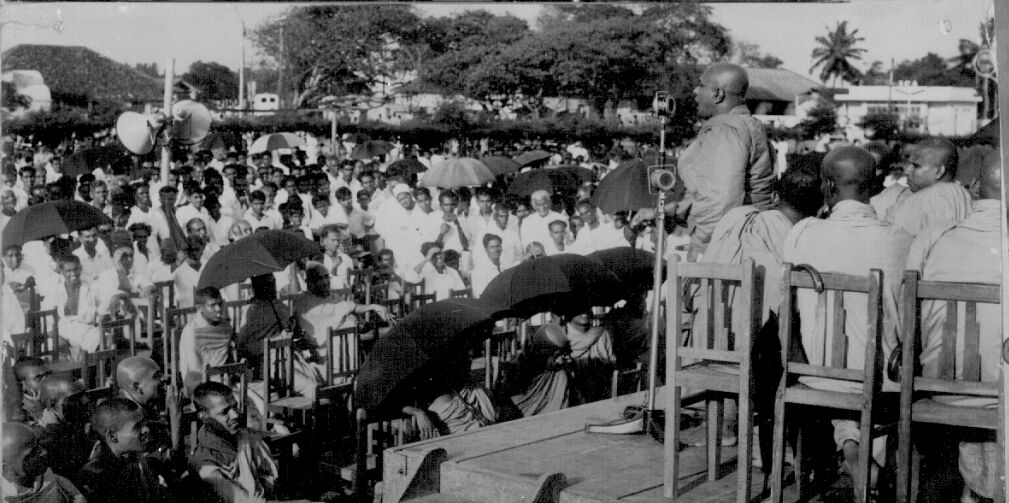

When Tamil political leaders attempted to stage a peaceful satyagraha protest against the act on Galle Face Green – the very green where Bandaranaike’s statue now sits and where today’s protestors are currently camped – they were attacked by mobs.

.jpg)

Photograph: Tamil protestors in Colombo, 1956, being attacked by a Sinhala mob led by Sri Lankan lawmakers. (Courtesy Victor Ivan)

“Hooligans, in the very precincts of Parliament House, under the very nose of the Prime Minister of this country, set upon those innocent men seated there, bit their ears and beat them up mercilessly,” recalled Somasundaram Nadesan. “Not one shot was fired while all this lawlessness to persons were let loose… Why? Orders had been given: ‘Do not shoot, just look on.’”

The violence from Galle Face spread across the island, as state-backed Sinhala mobs massacred Tamils. The events would become Sri Lanka’s very first anti-Tamil pogrom since gaining independence. More would follow.

Read more: Remembering 1956 – Sri Lanka’s first Anti-Tamil pogrom

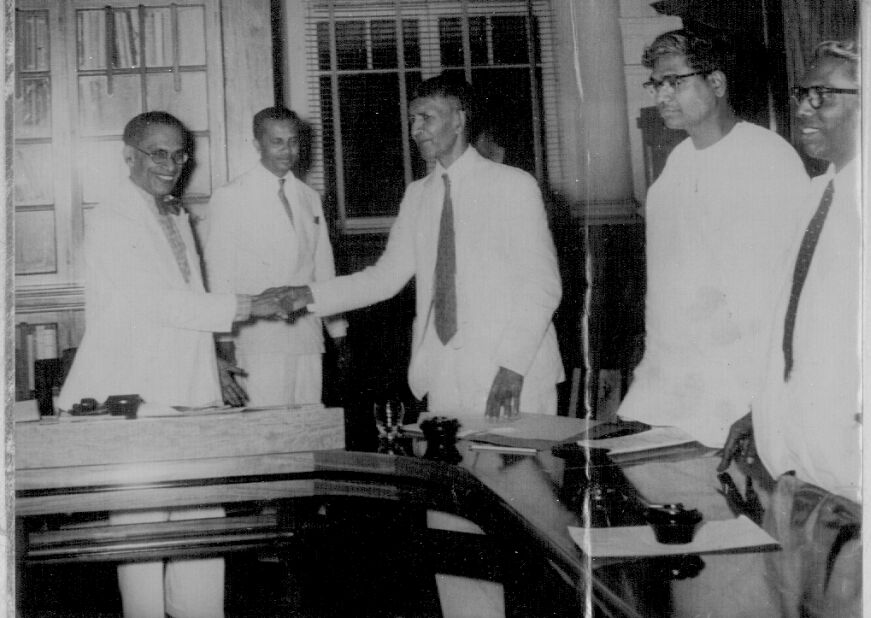

As violence on the island spread, Bandaranaike was eventually forced into negotiations with Tamil Federal Party delegates. After months of negotiation, Bandaranaike and Federal Party leader SJV Chelvanayakam agreed upon a settlement. The final toned-down list of concessions was disappointing to many Tamils, who had hoped for more in the negotiations.

“Chelvanayakam was not wholly pleased with the agreement, as was apparent when he returned home from the signing ceremony,” wrote A Jeyaratnam Wilson on the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayakam Pact of 1957. “He had been worried by the protracted negotiations. The failure to obtain a single merged Tamil-speaking North-East Province left him dismayed; he said that narrow district parochialism could emerge in the absence of all-embracing Tamil region.”

Bandaranaike and Chelvanayakam in 1957.

However, it was not Tamil discontent that would be the issue. Instead, the boiling Sinhala chauvinism that had gripped the South had taken umbrage. Buddhist monks in particular were incensed at the pact. The United National Party, led by future president JR Jayewardene, drew on that same virulent racism that Bandaranaike had utilised to lobby against the B-C pact, with rallies and marches denouncing it.

Despite Bandaranaike’s attempts to assuage the Sinhalese, telling crowds for example that “I am not merely a Prime Minister but a Buddhist Prime Minister”, he quickly caved. On April 9, 1958, after Sinhala Buddhist monks marched to his residence, Bandaranaike agreed to rescind the pact and on his front lawn symbolically tore up a copy of it.

Sinhala Buddhist monks protest.

“Yesterday, was the saddest day in the history of Ceylon’s racial relations,” reacted S Thondaman, the leader of Ceylon Workers Congress. “A solemn pact, worked out between the leadership of the country’s two main communities has been torn up because of the pressure of a group extremists. I am worried whether Tamils in the future will have trust in the Sinhala leadership.”

Read more: Remembering the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayakam Pact of 1957

Bandaranaike’s racism, however, did not end there. In 1958, as the Federal Party conducted a large-scale campaign of peaceful demonstration against the abrogation of the pact, Sinhala mobs launched yet another pogrom. A Hindu priest was burnt alive in Colombo, whilst mobs roamed the streets of Colombo checking whether passers-by could read Sinhala newspapers. Those who could not were beaten or killed. Estimates range from between 300 and 1,500 Tamils murdered in the days of violence which resulted in many more injured and the arson, looting and destruction of Tamil homes and businesses.

The prime minister waited five whole days before declaring an emergency.

Photograph: A Sinhalese mob beats a Tamil passenger after pulling him out of his car. 1958. (Courtesy Victor Ivan)

There was no apology for the violence from Bandaranaike. Instead, he accused “Federalists and other forces” of attempting” to overthrow the Central Government to set up a separate administration in the North and East” with several Tamil leaders arrested and imprisoned.

“I have thwarted that,” he reportedly declared. “Their attempts have been quelled. My military forces are now in the north and in the east. There is military rule in these two provinces, each with a military governor. Yes, I say they are military governors. With my army, I will see that there is no repeated attempt to set up a different administration in those provinces.”

Read more: Remembering the 1958 pogrom

The history of this man cannot be disputed. As the architect of one of the most racist pieces of legislation in the island’s history and a prime minister who oversaw two anti-Tamil pogroms which killed hundreds, Bandaranaike has Tamil blood on his hands.

Despite this chequered history, or perhaps due to it, Bandaranaike continues to evoke praise from Sinhala nationalists. In 1976, a bronze statue of Bandaranaike was unveiled on Galle Face Green – a gift from the Soviet Union at the time. To this day, it still stands there.

.JPG)

Current prime minister and accused war criminal Mahinda Rajapaksa walks past the statue at Galle Face.

In Sri Lanka, such monuments continue to have a searing impact on race relations. In the Tamil North-East, the Sri Lankan military has constructed several ‘victory’ monuments to mark their military victory over Tamil separatists in 2009, in a campaign that saw tens of thousands of Tamils massacred. To local Tamils however, the monuments are physical symbols of repression. “By promulgating a narrative of the conflict’s end as the triumph of good over evil, they reinscribe the divisions driving the violence and constitute a mode of forced remembrance for survivors who are not permitted to commemorate in their own way,” said People for Equality and Relief in Lanka (PEARL) in a 2016 report on memorialisation. “The monuments are so offensive to the victim community that those not located at military encampments are patrolled by armed guards, alert to the possibility of vandalism,” it added.

“We would not require a single day to tear down their monuments if the military was removed,” a Mullaitivu local told them.

It is a sentiment shared around the world, as statues of racist figures with chequered histories have been toppled and removed from public arenas. They are increasingly being acknowledged as problematic figures with complex pasts that need to be tackled not praised. Instead, there are proposals to display such statues in museums or other places of learning, so that future generations can learn from the cruelties of the past.

As protestors in Galle Face claim to demand a better future for all, the figure of Bandaranaike still stands over them. If Sri Lanka is to break free from the cycles of the past, the demonstrators must take the lead in tackling it. They should start with that statue in front of them.