With the war in Yemen well past its hundredth day, confusion persists as to the underlying causes of the conflict. Far from a sectarian proxy war between Shafi‘is under the patronage of Saudi Arabia and Zaydis backed by Iran, as the mainstream media would have it, the hostilities are rooted in local quarrels over power sharing, resources and subnational identities. These wrangles, in turn, are part of a broader negotiation process among domestic forces over a new social contract after the 2011 removal of the long-time president, ‘Ali ‘Abdallah Salih. At the core of this struggle lies a dispute about the future state structure, which provided the catalyst for the breakdown of the post-Salih transition road map sponsored by the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and the ensuing escalation to full-blown interstate war.

The continuing failure to bring the adversaries to the table recalls the civil war in North Yemen in the 1960s, when rivalries for regional hegemony between Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Britain prevented a local settlement between Yemeni royalists and republicans. Much to the same effect, today’s international support for President ‘Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi fuels the adamant insistence of his locally untenable government-in-exile on the implementation of the lopsided UN Security Council Resolution 2216, which calls for the unilateral withdrawal of Houthi fighters from captured territory and the resuscitation of the GCC initiative as preconditions for, rather than objectives of, talks. In order to break the deadlock, it is crucial to reopen a dialogue about the six-region federal division, which was rammed through, over the objections of the Houthis and others, at the National Dialogue Conference (NDC) that was intended to be the showpiece of the post-Salih transition.

Though hailed as a forum for averting Syrian-style civil war in Yemen, the NDC did not live up to expectations. As a Yemeni friend of mine sarcastically remarked after its conclusion in early 2014, “the NDC resolved all of Yemen’s problems—except for the secessionist strife in the south, the Sa‘da conflict in the north, national reconciliation, transitional justice and state building.” In other words, it failed to overcome every major stumbling block on its agenda.

The lack of genuine consensus on a new state structure proved the most salient shortcoming. As the NDC approached its original closing date in September 2013 with no agreement in sight, a subcommittee with eight representatives from each of north and south—known as the 8+8 Committee—was charged with finding a solution to the southern question. In its Agreement on a Just Solution, the working group, which included one Houthi delegate, unanimously affirmed that the Republic of Yemen—a unitary state with 21 governorates—should become a federal entity. This agreement was never revisited or approved by the NDC’s 565-member plenary, but simply accepted as a fait accompli.

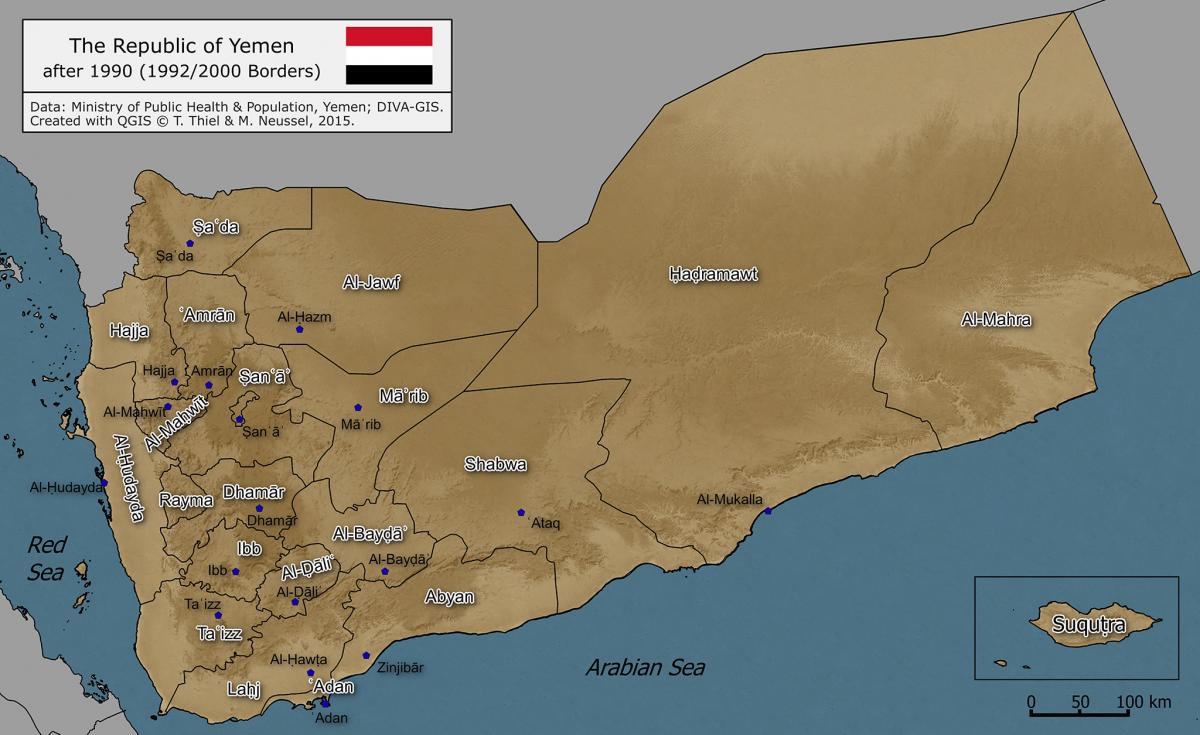

Though united behind the principle of federalism, the 8+8 Committee failed to settle on the number of new federal regions (two, five or six) or their boundaries. Instead, the committee outsourced these decisions to another fairly unrepresentative committee, handpicked and chaired by President Hadi, which was to study the parameters of a federal order. Established shortly after the release of the NDC’s final communiqué, this 22-member Committee of Regions took less than two weeks to delineate six new federal regions—Azal, Saba’, al-Janad, Tihama, Aden and Hadramawt. The process violated NDC rules, lacked broad consultation and was too short for the detailed studies that should have been commissioned. Nevertheless, its conclusions were referred to the Constitution Drafting Committee.

Even though all but the Houthi representative had signed off on the new map, most major political movements, including the Yemeni Socialist Party, the salafi Rashad Union and the southern hirak, as well as the Houthis, publicly rejected or expressed reservations about the six-region federal division. The Houthis argued that the plan distributed natural wealth unevenly. It deprived the Azal region, in which the Houthis’ historical homeland of Sa‘da is situated, of significant resources and access to the sea. Here the Houthis were referring, respectively, to the hydrocarbon-rich governorate of al-Jawf and the Red Sea province of Hajja, both of which the movement has traditionally considered within its sphere of influence.

Riding a wave of popular discontent with the transition, the Houthis radically altered the political landscape when they took control of the capital, Sanaa, in September 2014. The conquest fell just short of a coup, as the Houthis signed the Peace and National Partnership Agreement (PNPA) with President Hadi and others to relieve tensions. Articles 8, 9 and 10 of this agreement called on Hadi to reconstitute the National Body for the Implementation of NDC Outcomes, which was to revisit the state structure to align it with the NDC, rather than the Regions Committee, agreements.

Even before the draft constitution was released in January 2015, the Houthis reiterated their rejection of the six-region federal structure contained in the document. When Hadi nevertheless attempted to move forward the constitutional process by circumventing the PNPA, tempers flared. On January 17, the president sent his office director Ahmad bin Mubarak to deliver the draft document to the National Body, which had not been reconstituted. Enraged by this political intrigue, the Houthis flat-out kidnapped Mubarakto thwart the six-region federal order. The move set in motion a chain of provocations that culminated in the overthrow of the Hadi government, his escape into exile and the Saudi-led bombing campaign.

A crucial, albeit frequently overlooked fact is that the Houthis have repeatedly stated their acquiescence to a federal system—be it jointly with the hirak, in the form of a two-region federation, or in the form of a six-region division based on a sound political process. Rather than a rejection of federalism per se, the Houthis’ refusal of the six-region division is as much grounded in the lack of a genuinely inclusive decision-making process as in the specific parameters that undermine their interests. While none of this background serves to justify the Houthis’ recourse to arms, it does highlight the need for a new transition process based on equitable power sharing and sincere ownership across Yemen’s diverse political and geographic landscape as the only way out of the crisis.