by Sachi Sri Kantha, June 6, 2015

Prelude

As of now, in 27 chapters (and approximately 87,000 words), I was able to cover MGR’s life until 1962. I need to cover the remaining 25 years of his successful career, in which he transformed himself as a politician and a chief minister of Tamil Nadu. Writing at a snail speed of one chapter per month or two months, it had taken 30 months! I began this series in December 2012. Up to now, I have been guided mostly by MGR’s own autobiography, originally written during 1970-1972 and published in the Ananda Vikatan weekly. But, MGR failed to describe his life events in depth, after the death of his 2nd wife Sadhanandavathi.

Thus, biographers like me had to rely on the impressions published about him by those who had worked closely with him. Among these, one has to rely on the published writings of three different sources; (1) friends turned foes (such as M. Karunanidhi and poet Kannadasan), (2) those who worked under MGR for a salary (writing assistants K. Ravindar and Vidwan Lakshmanan, body guard K. P. Ramakrishnan), and (3) reminiscences of fellow colleagues for whom MGR was a patron in the movie field (script writer Aroordas, poet Vaali and comedians Nagesh, Cho Ramasamy) and in administrative affairs (police chief K. Mohandas). Views of the fourth source (academics, critics and journalists such as Robert Hardgrave Jr., and M.S. S. Pandian) should be ignored. But, they have their own in-built biases as well. I plan to write the remaining chapters chiefly from these sources, and as much as possible I avoid using hagiographic descriptions on MGR’s life published in short Tamil books and booklets.

‘Turns’ in Cinematic Life

In chapter 111 of his autobiography, MGR identified 14 of his movies as providing ‘turns’ in his cinematic life, among a cumulative total of 133 movies in which he had starred. These were,

1st turn: ‘Rajakumari’ (The Princess, 1947); debut as hero.

2nd turn: ‘Maruthanaatu Ilavarasi’ (The Princess from Marutha Land, 1950); pairing with V.N. Janaki and its difficulties.

3rd turn: ‘Marma Yogi’ (Mysterious Mystic, 1951)

4th turn: ‘Malai Kallan’ (Mountain Thief, 1954)

5th turn: ‘Nadodi Mannan’ (Vagabond King, 1958); double role, own production.

6th turn: ‘Thirudathe’ ( Don’t Steal, 1961)

7th turn: ‘Thai Sollai Thattathe’ (Don’t reject Mother’s Words, 1961)

8th turn: ‘Enga Veetu Pillai’ (Our Own Child, 1965); double role.

9th turn: ‘Kaavalkaaran’ (Protector, 1967)

10th turn: ‘Kudiyiruntha Kovil’ (Family residing temple, 1968); double role

11th turn: ‘Oli Vilakku’ (Light Lamp, 1968) – 100th movie

12th turn: ‘Adimai Penn’ (Slave Woman, 1969); own production

13th turn: ‘Maatukara Velan’ (Cowherd Velan, 1970); double role

14th turn: ‘Ricksawkaran’ (Rickshaw Guy, 1971)

Heroines of 1950s

Decade-wise ‘turns’ in MGR’s cinematic life tally shows, 1940s – 2 movies; 1950s – 3 movies; 1960s – 8 movies, and 1970s – 1 movie. Thus, MGR himself considered that he was at his peak in 1960s. Unfortunately MGR do not provide any descriptive details for these movies from the production angles. Only three movies, Rajakumari (1st turn), Maruthanaathu Ilavarasi (2nd turn) and Thirudathe (6th turn). Listed among the 14 ‘turns’, were his two own productions, Nadodi Mannan (5th turn) and Adimai Penn (12th turn).

As of now, other than occasional mention of his third actor-wife V.N. Janaki (1923-1996) and P. Bhanumathi (1925-2005), I have hardly mentioned MGR’s heroines. Since 1947, when he received hero billing, up to 1958, MGR’s heroines were born in 1920s and first half of 1930s. The year of birth of MGR’s first heroine K. Malathi (a Telugu actress) who starred with him in Sri Murugan (1946) and Rajakumari (1947) is not available in the sources I’ve collected. Prominent among MGR’s other heroines of 1950s were, P. Bhanumathi, Anjali Devi (1927-2014), B.S. Saroja (b. 1922?), Sri Ranjani Jr. (1927-1974), Madhuri Devi (b. 1929) Padmini (1932-2006), Savitri (1933-1981), E.V. Saroja (1936? – 2006), and Jamuna (b. 1936). As is well known for movie actresses in other countries, birth years of this breed have to be accepted with some reservation for the single reason that birth records in the early decades of 20th century India were not properly maintained, and majority of the births took place at homes and not in hospitals.

Only after gaining stature as a hero with box office potential in the latter half of 1950s, MGR came to dictate terms to the producers, whom he’d like to have as his heroine. With the possible exception of Padmini (who got married in 1961), most of MGR’s heroines of 1950s (Bhanumathi, Anjali Devi, Madhuri Devi and Savitri) were of married types and they had earned their spurs before MGR could gain a firm hold at the top of Tamil cinema. Thus, it may not be a wrong view to hold that from 1960s, MGR choose younger, unmarried heroines as his muses.

MGR’s Four Muses of 1960s and 1970s

Nine muses (Clio, Calliope, Erato, Euterpe, Melpomene, Polyhymnia, Terpsichore, Thalia and Urania) were recognized in Greek mythology. They were identified as the daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne (Memory), and conceived as minor goddesses who inspired poetry, music and drama. Even in the 20th century, this muse concept prevailed for poets and artists. Nine women were identified as muses of Pablo Picasso (1881-1973); namely, Germaine Gargallo (1881-1948), Fernande Olivier (1881-1966), Eva Gouel (1885-1915), Gaby Lespinasse (1888-1970), Olga Khokhlova (1891-1955), Marie-Therese Walter (1909-1977), Dora Maar (1907-1997), Francoise Gilot (b. 1921) and Jacqueline Roque (1927-1986). What is interesting are the facts that, (1) the ages of Picasso’s muses decreased from same age to 46 years younger. Picasso married only two of his muses. (2) Picasso married only two of his muses, Olga and Jacqueline.

If cinema was the 20th century art form, the same muse concept applied for popular and predominant actors and directors. Among his heroines, multi-talented Charlie Chaplin (1889-1977) had three muses; namely, Edna Purviance (1895-1958), Georgia Hale (1906-1985) and Paulette Goddard nee Levy (1910-1990). These three muses were 6 – 21 years younger than Chaplin. Chaplin married only Goddard.

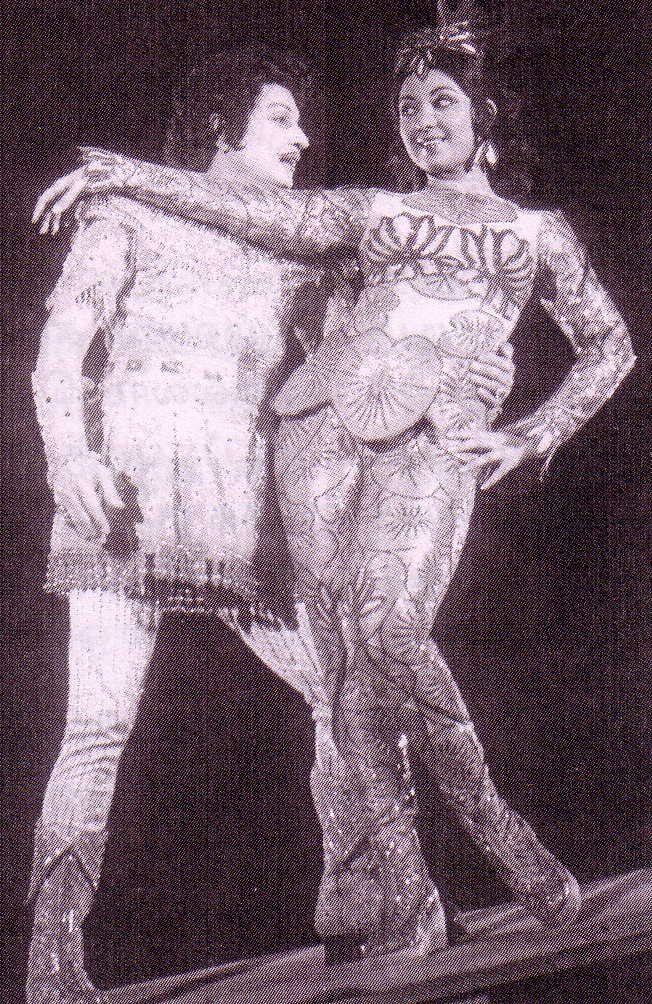

Similarly, MGR also had four muses, who played the heroine role in majority of his 133 movies. They are, B. Saroja Devi, Jayalalitha, Manjula and Latha. The age difference between MGR and these four muses were, 21 years (Saroja Devi), 31 years (Jayalalitha) and 36 years (both Manjula and Latha). One who dominated MGR’s movies in the first half of 1960s was B. Saroja Devi (b. 1938). Three of MGR’s chosen 1960s movies, Thirudathe (6th turn), Thai Sollai Thattathe (7th turn) and Enga Veetu Pillai (8th turn) featured her. Saroja Devi also had appeared previously as a second heroine in MGR’s own production, Nadodi Mannan (5th turn). Then, Jayalalitha (b. 1948) came to dominate MGR’s movies in the second half of 1960s. Saroja Devi got married in 1967. Check the fact that there is a ten year age gap between Saroja Devi and Jayalalitha. Five of MGR’s chosen 1960s movies, Kaavalkaaran (9th turn), Kudiyiruntha Kovil (10th turn), Oli Vilakku (11th turn), Adimai Penn (12th turn) and Maatukara Velan (13th turn) featured Jayalalitha. Saroja Devi and Jayalalitha did appear together in one MGR movie, Arasa Kattalai (King’s Command, 1967), which was touted as the one show a ‘rejuvenated’ MGR, after his gun-shot injury. More about this incident, later.

K.R. Vijaya (b. 1948), another competent heroine, was also paired with MGR in 1964 and 1965 for three movies. In one additional MGR movie (Kanni Thai/ Virgin Mother, 1965), Vijaya shared the second billing with Jayalalitha. But in the subsequent year, Vijaya got married and temporarily left the arena for childbirth. This made it easier for Jayalalitha to become MGR’s leading lady, until the latter switched his interest to two muses in 1970s, who were younger than Jayalalitha. These two, in the chronological order, were Manjula (1953-2013) and Latha (b. 1953). MGR had identified his 14th turn with the Ricksawkaran (1971) movie, which featured Manjula.

As his autobiography ends in October 1972, with his eviction from post-Anna DMK party, MGR became more interested in politics after founding his splinter Anna DMK party and building it as alternative option for DMK in Tamil Nadu. Thus, the final 16 of MGR movies (released between 1973 and 1978) in which his fourth muse Latha appeared (a total of 12 movies) never receive mention at all.

Vagaries of Indian Censors

Ruling politicians of Congress Party of post-independent India in 1950s found it easier to apply censorship rules indiscriminately for free expression of political activism that differed from their viewpoint. Movies were not exempt from censorship scissors. In a paper presented on June 7, 1951, K.M. Modi (then President, The Indian Motion Picture Producers’ Association) commented on censorship as follows:

“Every picture has to be censored before it is exhibited. There is a government nominated Censor Board for this purpose. Till the end of 1950, pictures were censored by State government boards. This gave rise to innumerable difficulties. A picture certified in one State was sometimes banned in another and vice versa. After repeated requests from the trade, censorship has now become a Union Government concern. There is now a Central Board of Film Censors situated at Bombay with regional offices at the three important centres of production, Bombay, Calcutta and Madras. The regional offices examine the pictures produced in their respective regions and issue certificates valid for the whole of India.”

To illustrate the trend of those times, I provide two paragraphs from Barnouw and Krishnaswamy’s ‘Indian Film’ (1963).

“The [Indian] Constitution itself, in its Article 19, had established ‘the right to freedom of speech and expression’. India’s First Amendment, adopted in 1951, whittled this down by authorizing parliament to enact ‘reasonable restrictions’ on the freedom of speech and expression [Note: emphasis by Sachi] ‘in the interests of the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, decency or morality, or in relation to contempt of court, defamation or incitement to an offence.’ Thus censorship in India acquired a firm, explicit constitutional base, which has given the government censorship powers almost impossible to challenge. A court could presumably interfere only on the ground that a restriction was ‘unreasonable’. To date there have been no court actions of this sort.

Operating on firm constitutional grounds, the Indian censors have proceeded with a sense of assurance. The Central Board of Film Censors which began functioning on January 15, 1951, has provided its examining committees with instructions that compromise a sort of code, listing types of material that maybe grounds for censorship action. Issued in November 1952, and subsequently revised from time to time, the list has retained items that date from colonial days of the 1920s, such as taboos on ‘excessively passionate love scences,’, ‘indelicate sexual situations,’ ‘unnecessary exhibition of feminine underclothing,’ ‘indecorous dancing,’ ‘realistic horrors of warfare,’ ‘exploitation of tragic incidents of war,’ ‘blackmail associated with immorality,’ ‘intimate biological studies,’ ‘gross travesties of the administration of justice,’ as well as material likely to promote ‘disaffection or resistance to Government.’ ”

Apart from trying to preserve the modesty of Indian women, Censors were also given the power to not to criticize the ruling party of the day. As far as the Tamil movies of 1950s and early 1960s were concerned (when the Congress Party had majority in the then Madras State legislature and the Central Government), any overt propaganda for DMK party by the actors, script writers and lyricists was clipped by scissors of sycophantic Censors. An interesting comparison should be made between the movies of MGR and his rival Sivaji Ganesan (who was with DMK until 1957, and later became unaffiliated and subsequently affiliated himself with the Congress Party leader Kamaraj). None of Sivaji Ganesan’s movies had problems with the Censors. But, the movies of MGR and especially the two movies [Raja Desingu, 1960 and Kanchi Thalaivan, 1963] in which SSR co-starred with MGR (both prominent DMK actors of the day) had problems with the Censors.

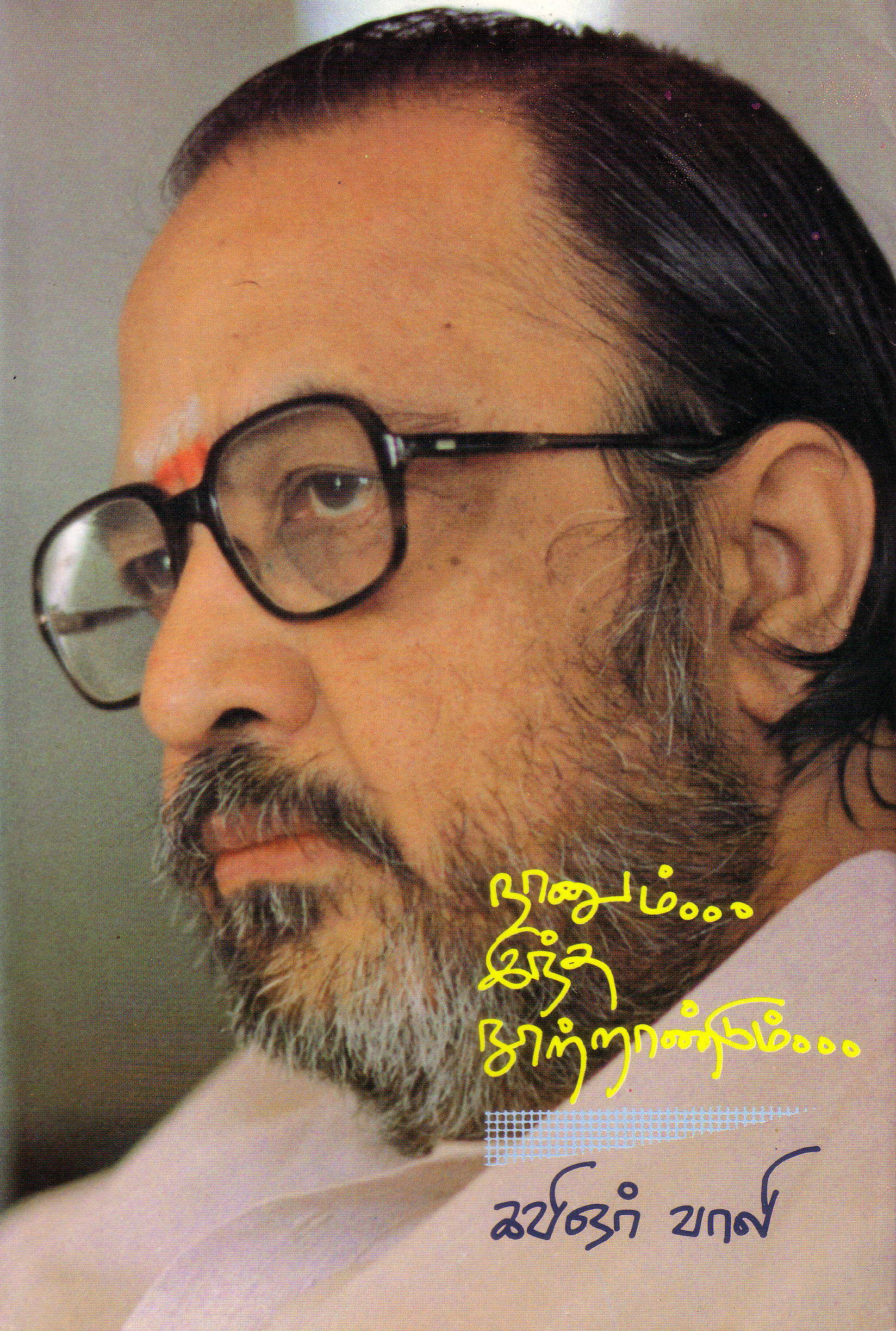

In between these two movies, one MGR movie Nallavan Vazhvan [The Good one will live] was released in 1961. The script writer for this movie was MGR’s mentor Anna. Though financially not a successful movie like MGR’s other movies of that period, it has one recognition. Poet T.S. Rangarajan (aka Vaali, 1931-2013) wrote his first lyric (a duet) for MGR. At that time, there was bad blood between MGR and his pal poet Kannadasan. Thus, MGR opted to promote Vaali as his favorite lyricist. Lady Luck also smiled on Vaali, because one who could have competed with him, Pattukottai Kalyanasundaram (1930-1959) had died in a botched operation.

I provide a translation of excerpts from Vaali’s autobiography below, in which he describes how few lines of his debut lyric for MGR were clipped by the Censors.

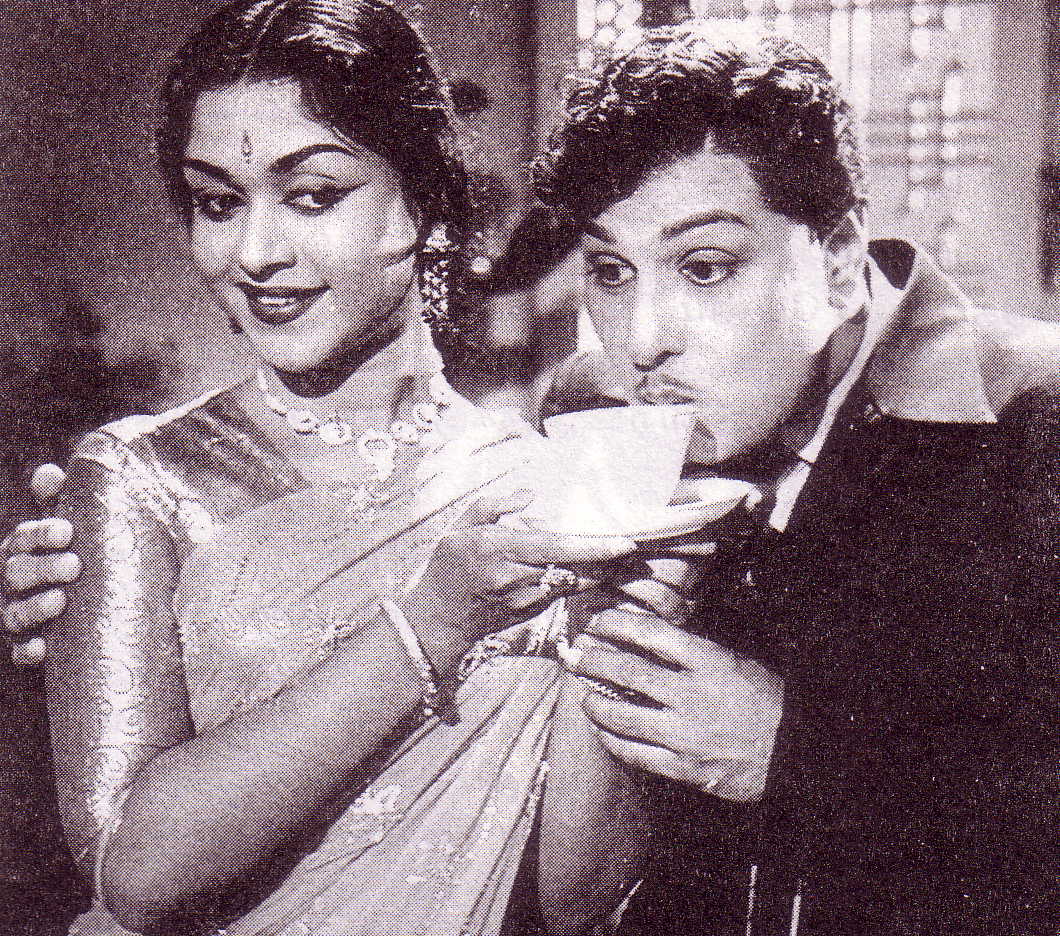

“The movie’s title was ‘Nallavan Vazhvan’. The song I’d to write was a love duet for MGR and Rajasulochana. I wrote about 50 variations of the lyric during the night and the next morning, carried to Arasu Pictures. My mind pointed to me that my future depends on how I make use of this opportunity. Mohan took my lyric and showed them to director Neelakantan. Among those, Mr. Neelakantan picked up the one which began with ‘Sirikinraal Inru Sirikinraal’ [She’s smiling – now she’s smiling]. This was the first lyric I wrote for MGR. Thus, the movie Nallavan Vazhvan and the lyric it has a special place in my mind.

The entire lines of that lyric was sent to Anna. In the latter half of the lyric, he had underlined some words and impressed that they should appear without deletion. As it was praised by Anna himself, the pleasure I received then couldn’t be measured.

Then, Annan Mr. T.R. Paapa [the music director for the movie] sang the song to MGR. MGR had liked it. I felt a big relief that MGR had liked it.

The date for the recording of song was fixed at Saratha Studio. I prayed to all my favorite Gods and went to Saratha Studio. MGR came at 12 o’ clock. He mentioned that the background music for the lyric was unimpressive. As time to make changes were inadequate, the song recording was postponed.”

There were two additional postponements according to Vaali, because the duet singers (Sirkazhii Govindarajan and P. Sushila) were indisposed one after the other. Subsequently, the producer/director held the view that the lyric was inauspicious and wished to omit it altogether and choose a better lyric from Aiyampillai Maruthakasi (1920-1989), a senior lyricist. After reading the lines of lyrics penned by Vaali, Maruthakasi excused himself with the words that Vaali had written well and he was not willing to spoil the opportunity of a younger lyricist. Thus, it was decided by the producer/director to retain the lyric Vaali had written. Finally, few lines in the latter half of the lyric were deleted by the Censors as objectionable and received green light ultimately.”

Vaali did not indicate which lines were deleted by the Censors. But when we listen to the song, two lines ‘Udaya sooriyan ethiril irukkaiyil ullath thamarai malaratho’ [If rising sun is in front of it, wouldn’t the heart lotus bloom?] and Ethaiyum thaangum ithayam irunthaal, irunda Pozhuthum pularaatho’ [If one has a heart which can bear anything, wouldn’t there be a sun rise from darkness?] can be tagged as propaganda for DMK party. Rising sun was the assigned symbol of DMK party. ‘Having a heart to bear anything’ was one of Anna’s popular tag lines to overcome ill will and hardships.

Hardgrave, after interviewing Murasoli Maran (1934-2003; a film script writer/producer turned politician, and a nephew of Karunanidhi) in 1969, wrote that film censorship was consciously used by the Congress government to ‘undercut the [growth] of DMK. “One technique, he [Maran] says, was to censor and cut critical elements of a film so as to destroy the picture’s coherence and thus ensure financial failure.”

A paragraph from Hardgrave’s 1973 paper is reproduced below verbatim, to describe the outcome of the duel between the producer of MGR-SSR starrer Kanchi Thalaivan (1963) movie and the Censors. The producer(s) [Mekala Pictures] was none other than Karunanidhi-Maran duo in 1963.

“In producing films under close censorship, the DMK turned to subterfuge. The use of double meanings in dialogue became a DMK a forte. They also created a character called ‘Anna’ – the Tamil word for older brother and the popular name for Annadurai – who appeared in almost all the DMK films as a wise and sympathetic counsellor. In an historical film, for example, the dialogue might go, ‘Anna, you are going to rule one day,’ at which the audience would break into wild applause. The historical film was particularly useful for the party, for it provided both an opportunity to eulogize Tamil culture and the glory of the Tamil kingdoms and, at the same time, to subtly comment on current political affairs. Maran tells the story of one film, Kanchee Talaivar, about a Pallava king whose capital was the city of Kanchee (Kancheepuram). Not without coincidence, Annadurai was from Kanchee, and he was known as Kanchee Talaivar, ‘the leader of Kanchee’. The censors demanded a change of title, but, after all, it did refer to a Pallava kingdom. The DMK got the title, but the censors so badly mangled the film that it was a financial failure.”

The script writer for Kaanchi Thalaivan movie was none other than Karunanidhi. It was the 9th and the last MGR movie for which Karunanidhi wrote the script, thus ending the collaborative partnership that began with MGR’s debut movie as a hero Rajakumari in 1947.

Cited Sources

Barnouw E and Krishnaswamy S: Indian Film, Columbia University Press, 1963, pp. 208-209.

Beckson K and Ganz A: Literary Terms – A Dictionary, 3rd ed., Andre Deutsch, London, 1990, pp. 168-169.

Hardgrave RL. Politics and the film in Tamilnadu: the stars and the DMK. Asian Survey, 1973 March; vol.13(3): 288-305.

Modi, K.M. The Indian Film Industry. Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, 1951; vol. 99: 865-876.

Kavignar Vaali: Naanum Intha Noorandum [This Century and Me], Kalaignan Pathipagam, Madras, 1995, pp. 188-206. (in Tamil)

A correction: In one of early MGR movies, ‘Abhimanyu’ (1948) produced by Jupiter Pictures, Karunanidhi shared the script-writing credit with A.S.A. Sami. Thus, we can count 10 movies in which MGR and Karunanidhi had collaborated.

It is amazing to know how the Congress government used censor rules to suppress freedom of expression. Now, the BJP government too uses censor rule (friendly relations with foreign states) to block movies which document the atrocities of Sinhala government. Recent example is the ban on the movie ‘Poorkalathi Oru Poo’ which traces the life story of Eelam Tamil journalist and TV anchor Isaipriya.