In this chapter, I provide the complete word text of a cover-story essay (~ 5,700 words) authored by Deanna Hodgin, which appeared 25 years ago, in the Insight on the News magazine (Oct.22, 1990). According to a Wikipedia entry about this magazine, this print magazine, founded in 1989 (as a sister publication of conservative newspaper The Washington Times, ceased publication in 2004. This essay, carried quite a number of period photos, including one with LTTE theorist and spokesman Anton Balasingham (1938-2006) and his wife Adele (b. 1950).

As one would expect in a journalistic essay, in some instances, there’s a little bit of ‘history bending’ by Ms. Hodgin. The roles played by the then Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi and India’s gum shoes RAW in creating ‘rival Tamil militant groups’ after 1983, had been ignored. One never knows either it was due to Hodgin’s ignorance of old and recent Sri Lankan history, or whether she had relied on biased secondary sources too much without independent verification. Despite the omissions, I consider this essay is worthy of note for presenting an unusually balanced version in a magazine (then owned by the Unification Church, founded by South Korean preacher Sun Myung Moon, 1920-2012) which promoted a conservative agenda in Washington DC. Thus, passing references to early days of LTTE in early 1970s as, “roughly in the form of Fidel Castro’s early guerrilla organization” have to be taken with a pinch of salt.

Some of the individuals, author Hodgin had interviewed for the essay include, Anton Balasingham, Lalith Athulathmudali (then, the Minister of Education), Ranjan Wijeratne (then, the Minister of Defense), Brother Joseph (a student at the Roman Catholic seminary in Jaffna), Dr. Ganeshamoorthy (then, at Dr. Green Memorial Hospital, Manipay), Vijay (a worker at the Melfort tea estate, who had requested omission of his last name), Dharmendra (LTTE’s Mannar island area leader), Yogaratnam Yogi (an LTTE leader), Neelan Tiruchelvam (former nominated TULF parliamentarian, attorney and Colombo’s regular informant for foreign journalists and ‘diplomats’), army major Anil Amarasekera, H.L.D. Mahindapala (then editor of Colombo Observer newspaper). LTTE woman tiger Malini, army major Lal Weerakoon, Father Francis (then, in Mannar), Yoganudum (a tea plantation worker), B.N. Jayasekera (a dry goods merchant in Habarane) and army Lt. Jayesekera of 2nd Sinha Division.

What I find interesting were the nominal one or two sentence(s) quotes included in the essay, which were stereotypical to the individuals who had uttered them. Here is a selection of these.

Lalith Athulathmudali: “The LTTE can’t tell me they’re a victim of genocide. They’ve killed more Tamils than the Indian army, the Sri Lankan army and the other militant groups put together.” This quote had been repeated by umpteen times by other journalists, without verifying the numbers.

Ranjan Wijeratne: “We will push the LTTE into the salty waters of the Palk Strait.” History records that Mr. Wijeratne suffered an untimely death on March 2, 1991, within five months of the appearance of this essay.

Neelan Tiruchelvam: “The LTTE cadres must pledge absolute allegiance to both a cause and a personality. The organization is totalitarian and hierarchical in organization , and resilient. They are intolerant and distrustful of the existing political order.”

H.L.D. Mahindapala: “The Marxist rhetoric [of LTTE] is just an excuse to settle a one-party state with Prabhakaran at the head.”

Dharmendra: [on the cyanide necklace] “Oh, this! This is for when my enemy captures me for the torture. We may be hurt so much we betray our group. It is our duty to take this, Also, we should take this if we become badly injured, a burden to the movement.”

Malini: “She [referring to her mother, who had supported her decision to fight] says it’s better than staying in our village. There, I would probably be killed by bombing or helicopters, as many of our neighbors have. Or molested by army soldiers, which in my culture is worse than dying.”

The one I liked best, was from army Lt. Jayesekera of 2nd Sinha Division. To Deanna Hodgin, he had opined, “I have fought from 1983, both North and South, and have been injured 42 times…Will the LTTE lose? I don’t know, they also have a dream. They also have a plan. It’s like two trains on a collision course. They both keep going.”

The descriptions which appear in this essay, relates to the period prior to Eelam War II, which began in June 1990, when LTTE leader Prabhakaran was only 35. Many individuals who had been interviewed by Ms. Hodgin (Balasingham, Athulathmudali, Wijeratne, Tiruchelvam, Yogi, Dharmendra and probably Malini) are no more now. But, gutter journalist Mahindapala lives in Australia, still spinning fiction filled with filth about how great Mahinda Rajapaksa was for the Eelam Tamils. From a couple of recent news reports, I guess Maj (then). Lal Weerakoon quoted in this essay, is still living. But, I’m not sure whether other two SL army folks Anil Amarasekera, and Jayesekera are still living.

*********************************************************************

Complete Text [Note by Sachi: Spelling of names and places are, as they appear in the original. In addition, there were six brief box stories, some I provide as scanned material.]

An Ethnic Inferno in Island Paradise

by Deanna Hodgin [Insight on the News, Oct. 22, 1990, pp. 8-18]

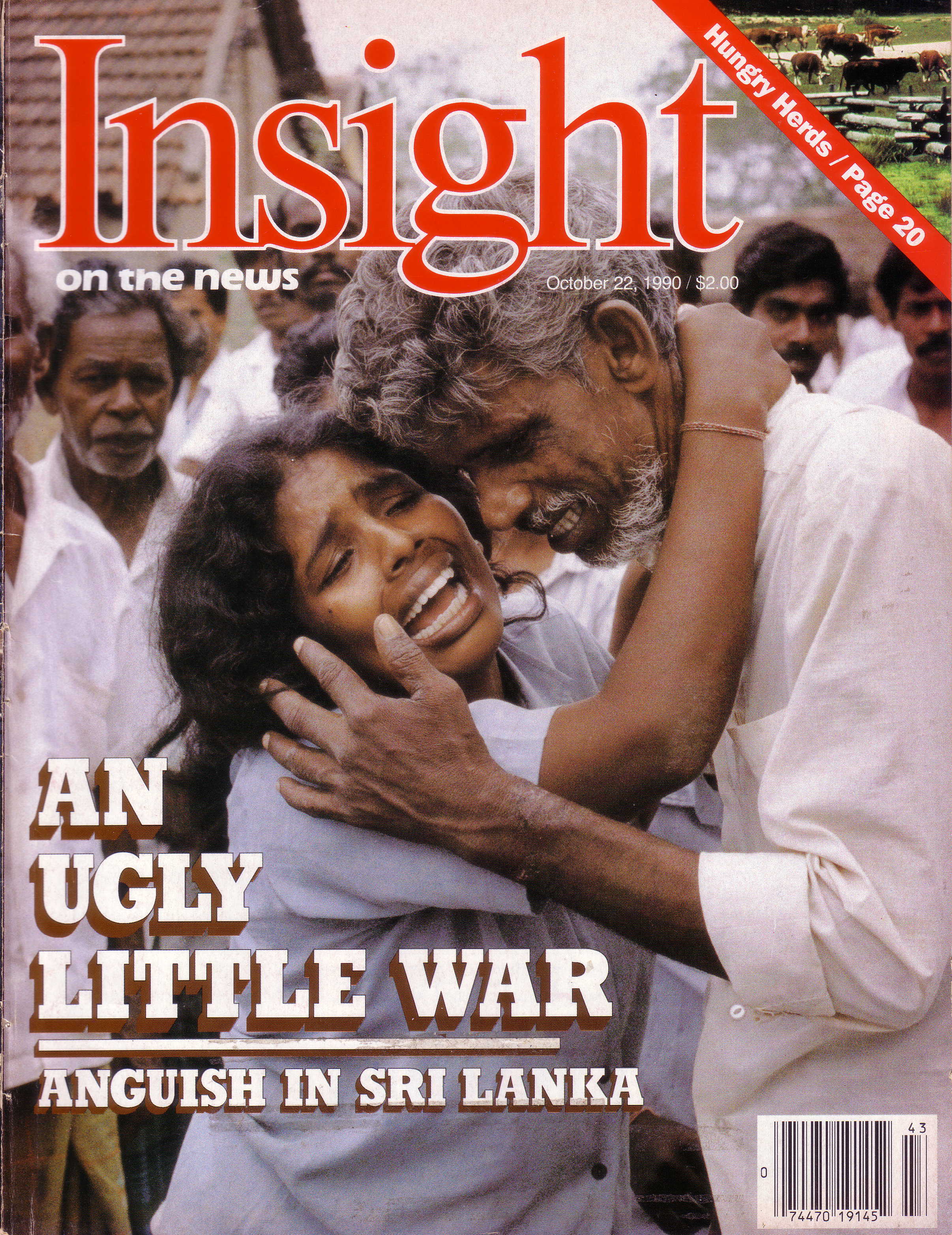

SUMMARY: Once the jewel of South Asia, Sri Lanka is torn by a civil war between the Sinhalese majority and a radicalized Tamil minority, a conflict that dates back 2,500 years. The recent fighting is the worst yet, the Sri Lankans say, with communal hatred fueling new feuds within the Tamil community and between Tamils and Musims. The mostly Sinhalese government, while talking peace, has embarked on the most ambitious military campaign in the island’s history.

It is the oldest democracy in Asia, a modern-day treasure island in the Indian Ocean that was once a prime candidate for the next Asian economic miracle. But beneath the travel poster promise of serene white sands and palms and some of the best surfing in the world, racial hatred has eaten through the body of Sri Lanka.

Since June 11, a war has raged in the north and east of the island between the government and armed militants of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, a self-proclaimed national army of Sri Lanka’s minority Tamil population. The LTTE is fighting for a separate, Tamil-administered state. Despite fervent government denials, the fighting has a definite communal bent.

Bad blood between the majority Sinhalese and the Tamils goes back 2,500 years, to dynastic rivalries of successive Tamil Hindu and Sinhalese Buddhist kingdoms. The rhetoric is as extravagant as the killing is brutal. ‘What you see – the helicopters flying around and strafing marketplaces, shooting at civilians – it’s a manifestation of a phenomenon of genocide,’ says Tamil Tiger spokesman Anton Balasingam from the edge of his bunker. Back in Colombo, the capital, the former defense minister, now minister of education, scoffs at that claim. ‘The LTTE can’t tell me they’re a victim of genocide,’ Lalith Athulathmudali says. ‘They’ve killed more Tamils than the Indian army, the Sri Lankan army and the other militant groups put together.’

This conflict has escalated into what both combatants call a battle to the death. ‘We will push the LTTE into the salty waters of the Palk Strait,’ says Defense Minister Ranjan Wijeratne. ‘We will fight until the last cadre,’ respond liberation leaders.

It is another of the Third World’s dirty little wars that few in the peaceful, prosperous West bother themselves about – part of the neglected cycle of human misery that includes Joseph Stalin’s 1930s Ukraine adventures, Nigeria’s Ibo Rebellion, the Turkish and Armenian wars. Despite the recent democratic developments in Eastern Europe and hopeful noises, of late, about the democratic potential of the postcrisis Persian Gulf sheikhdoms, the continuing use of terror against civilians in scenic, democratic Sri Lanka has taken place by and large without remark.

A Walk Through Jaffna

The main streets of Jaffna the northern peninsular town that for centuries has been the center of Tamil culture, are bloodstains and broken pavement. Helicopters have strafed the Rev. Green Memorial Hospital, the only medical center operating on the peninsula. Children scream ‘Heli!’ and scatter when the Bell 420s go nose-down over the neighborhoods spitting storms of bullets. Fractured terra-cotta roof tiles and telephone poles bent double fill the wide avenues that used to connect the bustling commercial center. Chipmunks steal cough drops from a pharmacy whose brick walls have spilled over adjoining properties. The air is chopped by shock waves from navy shelling, air force bombing and the gunfire of fighter planes. Army mortars fired by troops advancing from outside the town are to Earth, creating dirt fountains. Schools, vacated for an indefinite summer break, shelter close to 1 million displaced Tamils.

At night, the broken streets fill with refugees toting all they can carry. Fights break out in the mile-long line of families waiting to leave Jaffna. The atmosphere is charged with fear, as desperate families battle to pay the equivalent of a week’s wages to each space aboard one of the fishing boats that violate the government imposed curfew. The boats ferry refugees from Jaffna Peninsula across the Jaffna lagoon to the main island. The refugees speak in whispers so as to hear the approach of helicopters.

The Sri Lankan air force attack on Aug 22 at Jaffna Lagoon was ‘typical, the way it happens two or three times a week,’ says Brother Joseph, a student at the Roman Catholic seminary in Jaffna. ‘They swoop down, and out on the pier, here in Jaffna and on the other side, there is nowhere to go. Four people were killed, 22 injured.’

Government newspapers inflate the numbers and recast the dead as terrorist insurgents. ‘The constant bombing, shelling, firing going, it interrupts all life,’ says Joseph. ‘And now there is little food, what’s available is too costly, and there is the beginning of famine.’ For most Tamil refugees, crossing the lagoon is a trial run for an even riskier ocean crossing, to refugee camps in India. From the Jaffna lagoon, the refugees walk nearly 100 miles to illicit ports of departure.

Sad History

When, in 350 BC, Buddhism began to lose ground to Hinduism in its Indian birthplace, Sri Lanka’s Sinhalese took on the self-appointed role of keepers of the flame. Repeated invasions by South Indian Tamil forces pushed the Sinhalese south, planting seeds of resentment and fear of invaders from the north. The various colonial periods – the Portuguese (1505-1658), Dutch (1658-1796) and British (1796-1948) – did little to dispel the enmity. Nor has it abated much since independence in 1948.

Sri Lanka’s Northern Province begins at the tapered tip of the island, where several small islands lead into a peninsula that widens into the mainland. The white beaches of the north turn into the dusty, scrub-covered interior that in turn leads to a center of jungles and swamps. The province’s majority population is Tamil. Roughly one-third of the way down, the center of the island is divided into the North Western, North Central and Eastern provinces. (Northern and Eastern provinces were merged into the Northeastern Province as part of negotiations between the government and the Tamil rebels in 1987. The merger is contested by the more militant members of the Sinhalese community.) The agriculturally rich East is populated in roughly equal parts by Sinhalese, Tamils and Muslims. It is also the site of a major prize, Trincomalee Harbor, one of the finest deepwater harbors in the world. The Central Province fills the core of the island, while the Uva, Sabragamuwa, Western and Southern Provinces make up the south. The central and the southern regions are mostly Sinhalese.

The Eastern Province is, in many ways, a key to the current struggle. The Tamil Tigers claim the East as part of their homeland. Government strategy has focused on uncoupling the East from the North, to destabilize the Tigers’ campaign for a combined province as a separate state. ‘The East is claimed by the Tamils, the Sinhalese and the Muslims,’ says a government minister. ‘It’s the result of an artificial demarcation by the British.’ The LTTE, for its part, says the East was deliberately imbalanced by the interjection of Sinhalese settlers sent by the government. The Sinhalese respond that there were never Tamil establishments more than four miles from the coast, that the East was traditionally part of the Sinhalese Kandyan kingdom. Eastern Province Muslims point out that who arrived first is less important than who has lived therefore the past few centuries, as they have.

The liberation group counts as constituents the island’s Muslim community, a group that had developed its own agenda over the past decade, not always in line with the separatists’. The business boosterism of President Ranasinghe Premadasa has won over more than a few Muslims, the traditional urban merchant class.

The liberation group counts as constituents the island’s Muslim community, a group that had developed its own agenda over the past decade, not always in line with the separatists’. The business boosterism of President Ranasinghe Premadasa has won over more than a few Muslims, the traditional urban merchant class.

Moreover, there are Tamils and then there are Tamils. The so-called estate Tamils are Southern Indians imported during the years of British rule to create and staff the rubber, coconut, coffee and, later, tea estates of Central and Eastern Sri Lanka. The Eastern Tamils do not always throw in their lot with their Northern kin. ‘The lives of estate Tamils are not so prosperous,’ says Vijay, a worker at the Melfort tea estate who asks that his last name not be divulged for fear of rebel reprisal. The estate is at the beginning of Sri Lanka’s central hill country, in Pussellawa, a vertical, green town of tea-covered hills that must be taken in low gear. ‘My family? I don’t know where we’re from. I guess India, but we’ve lived here a long time,’ he says.

The estate Tamils’ lack of interest highlights a fundamental historical divide within the Tamil community, one the government has exploited to its own advantage in this most recent fight. Many Sinhalese say the separatists’ claims of unity with the Muslims and outrage over the estate Tamils’ plight are feigned indignation.

Massacres of Sinhalese and Muslim villagers in the hundreds have become a feature of a recent fighting. The Muslims and Sinhalese blamed the LTTE, and the Eastern Province Tamils are increasingly siding with their neighbors, rather than their relations up north. A gruesome massacre Aug. 3 at a mosque at Kattankudy, in which 140 died and 125 were wounded, has become a focus for finger-pointing. Who really was responsible?

The government blames the Tamil Tigers. ‘It was not done by us,’ counters the Tigers’ Mannar Island area leader, Dharmendra. ‘It was done by the government, so they would get arms from the Islamic countries. When it happened, the defense minister was in Libya, a strange coincidence.’ The government denies involvement in the killings, and most Western diplomatic sources seem convinced of the government’s claims.

After the massacre, the government began an aggressive program of arming and giving rudimentary training to young Muslim men as members of the Muslim Home Guards. Knots of young boys stack their bicycles against trees at the Sri Lankan army’s Vavuniya outpost. They return shortly with new rifles and fistfuls of bullets wrapped in their bright plaid sarongs. The number and regularity of killings have increased in the East since the arming of the Home Guards.

Residents of Batticaloa, the lagoon-straddling Eastern town long a site of militant clashes, speak of factions within the Muslim community there and revenge killings between the three ethnic communities that used to coexist. Golden, ripe fields of paddy sway in the musky heat of late summer before the monsoon. ‘No one can harvest the rice this year,’ says an elderly Muslim woman, returning from prayers at the massacre victims’ graves. ‘People go to the paddy, they disappear.’ The Catholic bishop of Batticaloa speaks sadly of the disappearance of one of the Jesuits, the Rev. Herbert, an American citizen. ‘We have an idea of who might be responsible for the death of Father Herbert, but in the Eastern Province there are so many suspects. No one can be sure.’ Other church officials indicate the army had been active in the area where the priest was last sighted. Both the U.S. Embassy and the Roman Catholic Church in Colombo have been quiet about the elderly Jesuit’s disappearance.

The Rise of the LTTE

Public enemy No.1 grew out of a series of events beginning in 1956, when politician Solomon Bandaranaike, riding a regional wave of postcolonial nationalist fervor, was elected prime minister on a Sinhala-nationalist platform. The first piece of legislation he passed, the Sinhala Only Bill, made Sinhala the island’s official language, separated students into schools for Tamil or Sinhala instruction and put English-speaking Tamil civil servants out of work.

‘Well, if the Tamils are so bloody smart that they can master English under the British, why can’t they learn Sinhala?’ asks a high-placed Sri Lankan diplomat. In an earlier time, the Tamils might have swallowed their pride and accepted Sinhala. But the 1940s and 1950s were a regional renaissance for national and ethnic pride – the time of Gandhi, Nehru and Jinnah. Language riots raged in Colombo and in other cities, and the tradition of racial combat flared again.

At one of those riots in 1958, a 4-year old boy watched in horror as Sinhalese demonstrators tortured his favorite uncle. While the man was still alive, they set him on fire. That child, Velupillai Prabhakaran would grow up to create and lead the militant separatist Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. Says one cadre: ‘If they put education quotas to block our progress, leave our northern homelands economically undeveloped, rob us of our language rights and shoot us down when we don’t obey, what other choice do we have but to separate? They aren’t treating us as citizens, so why should we try to be citizens? This is what Mr. Prabhakaran asks us.’

Prabhakaran and 30 teenage companions from his Jaffna Peninsula fishing village formed the LTTE in 1972, roughly in the form of Fidel Castro’s early guerrilla organization. The rebel group grew in number and strength, training for guerrilla warfare at remote jungle bases. An aggressive capitalization plan of bank robberies and shakedowns of northern businesses financed a growing store of arms.

Despite its bold strokes, or perhaps because of them, the LTTE was not the party for all Tamils. In 1976, the Tamil United Liberation Front, a nonviolent political coalition of Tamil parties seeking an independent state of Eelam in the North and North-east, passed a resolution calling for a separate Tamil state. Elected to the National State Assembly, now the Parliament, United Liberation Front leader Appapillai Amirthalingam became opposition leader. In a country where the historical meaning of opposition politics has usually been that of a smattering of leftists (including exotic breeds, such as Trotskyists and Bolsheviks) and a few ethnic minority-based parties unable to coalesce, Amirthalingam made coalition seem possible, if only by force of personality (he was assassinated last year by the LTTE).

The election of Junius Jayawardene, a pro-Western pragmatist, as prime minister in 1977 spurred Tamil hopes for a solution to the growing conflict that had resulted in anti-Tamil riots in 1956, 1958 and 1977. Jayawardene held discussions with Amirthalingam and others on the potential for a devolution of the central government’s powers to the North and East through a provincial council scheme.

Yet by 1983, two more anti-Tamil riots had stoked communal anger. The negotiations had produced little substance. ‘We kept talking, kept waiting for them to give what they said they’d give us, but nothing happened,’ says LTTE leader Yogaratnum Yogi. The moderate Tamil party was under pressure from the militants for lack of results, just as Jayewardene was feeling squeezed by a militant Sinhalese group, the Janatha Vimukti Peramuna, or People’s Liberation Front. That group’s Marxist Sinhalese militants felt that Jayawardene was too lenient with the Tamils and any concession in the direction of the north would rob the south of its entitlement. The Sinhalese militants had led an unsuccessful armed revolt in 1971, in which thousands died.

Lightning struck in 1983, when Prabhakaran and 13 Tiger guerrillas attacked a Sri Lankan army convoy just outside Jaffna. The news of 13 soldiers killed by the increasingly violent Tamil rebels sparked a five-day riot throughout central and southern Sri Lanka, in which more than 1,000 Tamil civilians lost their lives. One hundred thousand Tamils lost their homes in an eruption of burning and plundering.

‘The continuing communal violence devalued democratic ideals and strengthened the appeal and seeming legitimacy of armed revolt,’ says Neelan Tiruchelvam, a Harvard-trained Tamil lawyer in Colombo and former parliamentarian. He says segregated schools contributed to racial hatred based on ignorance of the other culture. ‘This transformed many formerly moderate Tamils into militant separatists.’

Rival Tamil militant groups sprang up, but by 1986 the LTTE had crushed them and announced that it had taken over the civil administration of the Northern Province. The Tigers do not bother denying that it was bloody. ‘Of course, in Colombo, they will say that these fellows are wiping out all the opposition,’ says Tamil Tiger spokesman Balasingam. ‘But this is a life-and-death struggle for us, for our people. We are facing genocide. We can’t tolerate traitors, informants; otherwise we will perish.’

But traitors and informers were not the only ones on the Tigers’ blacklist; Sinhalese colonists in the Eastern Province were frequent victims of massacres in late 1986 and early 1987. ‘It was terrible,’ says an elderly woman who sells bread – when it is available – at the Batticaloa bazaar in that Eastern city. ‘Bodies in the lagoon, smoking bodies on the road. No one can touch, or whoever does this will come for you.’

In response to the rebels’ announced administration of the Jaffna Peninsula, the government stopped supplies of gasoline to the North and East. Intermittent talks faltered. When the Tigers bombed the main Colombo bus station in April 1987, the government decided it was war. On May 26, 1987, the Ministry of Defense began Operation Liberation in a bid to shut down the rebel group. More than 4,000 troops began a three-stage assault from four directions. After two weeks, the army was till in the first stage. It flinched. When the Indian government airlifted 22 tons of humanitarian aid to the militants, army morale sank. Operation Liberation stalled.

Fighting continued, as did talks between the Sri Lankan and Indian governments and secret meetings to define the demands of the various Tamil groups. In July of that year, Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and President J.R. Jayawardene signed the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord, an attempt to help Sri Lanka solve its swelling internal crisis. The cease-fire agreement attempted to compromise with the militant groups, by offering an amnesty for Tamil militants, putting the Tamil language on an equal official part with Sinhala, and the promise of potentially greater autonomy for the Northeast. India would also send a peace-keeping force to the island.

Complicating matters were the difference between Tamils and Sinhalese in their feelings toward India. Tamils look to India as an advocate of their aspirations and as a cultural touchstone. The Sinhalese see India as an expansionist power, and Sinhalese nationalism has been twisted by more than a few politicians into anti-Indianism. That antagonism has defeated earnest offers on the part of the larger nation to share its resources in solving the problems the island does not seem able to solve itself.

The presence of 7,000 Indian troops to police the accord went well initially but turned ugly when the LTTE repudiated the accord, saying it had not been consulted, and began attacking Indian troops. Although the government came through on several of the promised points, Tamil militants complain that it failed to adequately fund provincial councils and stacked elections in favor of its candidates. Former Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasa was elected president in a rare show of unity between Tamil and Sinhalese voters supporting his promise to get the Indian forces off the island. By March 1990, the last Indian troops were gone.

‘Ultimately, the worst result of the fighting is that we become opportunists,’ says an aid official in Mannar. ‘One day, we ask the Indians in to help with our problems; the next day, we want them out, they’re all devils. The day after that, we’re leaving for India, they’re the only ones who will protect us. We begin to justify anything that benefits us.’

The latest round of fighting began in earnest in mid-June after peace talks failed.

The LTTE Militants: Who are They?

When asked about LTTE founder and leader Prabhakaran, the young militants offer unadulterated, party-line praise. ‘Our leader is our morning star,’ says Dharmendra (the fighters take a single nom de guerre), leader of a 20-man command on Mannar island. He indicates one of many posters of the now-rotund guerrilla chief that decorate all cadre safe houses and many homes in the North. The photo’s calmly smiling subject is now 36, with a belly and stippled gray at the temples. Kitted out in the traditional LTTE tiger stripe camouflage, Prabhakaran smiles in houses and bunkers across the north and east of the island. The photo is worshipped by a few thousand of the toughest guerrillas in recent history.

‘The LTTE cadres must pledge absolute allegiance to both a cause and a personality,’ says Neelan Tiruchelvam. ‘The organization is totalitarian and hierarchical in organization, and resilient,’ says Tiruchelvam, pointing to the LTTE’s vanquishing of both the Sri Lankan and Indian armies. ‘They are intolerant and distrustful of the existing political order.’ LTTE leaders justify killing moderate Tamil politicians (one of whom was gunned down with his wife last year outside the Canadian Embassy in Colombo) as needed for self-protection.

‘The transport services from Colombo are completely cut off, there’s no food supply, no medicine, no electricity, no fuel,’ says Balasingam, the Jaffna-based Tamil Tigers spokesman. ‘Apart from that, there’s systematic bombing in Jaffna and the surrounding towns, which has taken out hospitals, power plants. As far as one could see, this is not an offensive operation against a particular group of people, the LTTE. It is directed against all Tamil people.’ Balasingam says this amounts to Sri Lankans’ declaring war against their countrymen. ‘If the government doesn’t recognize Tamils as citizens of this country, then we have no other choice but to separate ourselves from this state and create our own.’

Post-revolutionary ideology in the LTTE is vague. ‘First we’ll win our revolution, then we’ll vote to see how we will organize it,’ says cadre Dharmendra. Balasingam says the organization is socialist but has lately been trying to distance itself from its formerly avowed Marxism. ‘The Marxist rhetoric is just an excuse to settle a one-party state with Prabhakaran at the head,’ says M. Mahindapala, the editor of the Colombo-based Observer newspaper. ‘The history of Marxism has shown that, instead of the dictatorship of the proletariat, it becomes the dictatorship of the party, which becomes the dictatorship of one man. In that way, the LTTE could create a state like Pol Pot’s.’

The cadres, however, are less concerned with product than process. ‘To join the LTTE, first a young person must come and talk to me,’ says Dharmendra. ‘I’ll tell him about the hardships of this life, and let him think it over. Once he says yes, we begin training.’ Initiation involves rigorous training and sometimes severe hazing. Education encompasses arms and ammunition handling, reconnaissance, survival and geography, as well as the history and beliefs of the group. ‘The lessons are tough,’ says a 17-year old recruit, ‘and if you don’t study, there will be punishment.’

Part of the organizational loyalty for each member is to wear a cord with a small bottle of poisonous tablets attached to it – the famous cyanide necklace. ‘Oh, this,’says Dharmendra, fingering his scruffy amulet. ‘This is for when my enemy captures me for the torture. We may be hurt so much we betray our group. It is our duty to take this,’ he says, bouncing the necklace off his bony chest. ‘Also, we should take this if we become badly injured, a burden to the movement,’ he says matter-of-factly. Posters of those who have martyred themselves for this cause cover the storefronts and walls of Jaffna, plastered over layers of older martyrs.

The LTTE gladly accepts women recruits. At night, the main intersections are guarded by women Tigers. In the day time, bright-faced young women clothed in camouflage and toting rifles pedal two to a bicycle down the roads. Their nationalist commitment has a feminist edge. Malini, leader of the rebel women, attributes their attraction to the group to its repudiation of the Hindu caste system. ‘In Tamil society, marriage is a big problem, especially for the poor girl,’ explains Malini. ‘So many girls cannot marry because they don’t have enough money for dowry.’ Under the Hindu dowry system, the bride’s family must pay a large sum to the groom’s family, and prices rise according to the prestige of profession. ‘Because of money, the right of family life is refused poor girls,’ says Malini.

Sometimes the rigors of militant life are more psychological than physical. ‘Leaving one’s family is hard, breaking the bond of the joint family system,’ says Malini. ‘It’s painful for me sometimes, when I go to defend the village, and you see a family – a mother and daughters – and you remember you’re not a family girl anymore. You’re a soldier.’

Malini says her mother worries about her but supports her decision to fight. ‘She says it’s better than staying in our village. There, I would probably be killed by bombing or helicopters, as many of our neighbors have. Or molested by army soldiers, which in my culture is worse than dying.’ Both Amnesty International and Asia Watch have reported rapes and molestations by members of the Indian and Sri Lankan armies.

But the LTTE is also a violent militant organization. Since June, civilian deaths attributed to it have spiraled. The government pins responsibility on the group for the hacking deaths of hundreds of Sinhalese farmers in Eastern farming villages, the razing of Tamil and Sinhalese villages in retaliation for cooperating with government forces, as well as the Kattankudy mosque massacre. In the first week of October, Colombo’s The Island newspaper rported that rebel massacres and threats forced 46,000 refugees to leave government camps in the North Central region. ‘The opposition groups have themselves committed atrocious crimes,’ Amnesty International said in its Sept. 18 report on human rights abuses in Sri Lanka. ‘but the government must not use this as an excuse for like brutality that violates basic rights. It must act now to halt the continuing violations.’

A Pattern of State Terror

As gruesome as the massacres and retaliation is the repetition of mass killing by government forces, a solution to opposition that appears to have become policy. Amnesty International notes observers’ reports tht in 1988-89 as many as 30,000 people were killed or ‘disappeared’ by the government in its fight against the Marxist Sinhalese People’s Liberation Army (the JVP) in the south of the island. President Premadasa, in a June speech, said that ‘the fate that befell the JVP was a result of their not heeding the appeals made by us to come around for discussions and restore peace….If [the Tigers] continue with these crimes, I could only say that it is certain that the same fate that befell the JVP would befall them, too.’

Aid agencies estimate as many as 4,000 casualties from the fighting over the past three months. Human rights organizations note the frequent disappearance of those who oppose the government and the torture and extrajudicial killing of suspected insugents by an extraordinarily powerful armed force, a security force that has the authority to stop, search, detain for up to 18 months without charge, and to beat, shoot and cremate without medical inspection of remains.

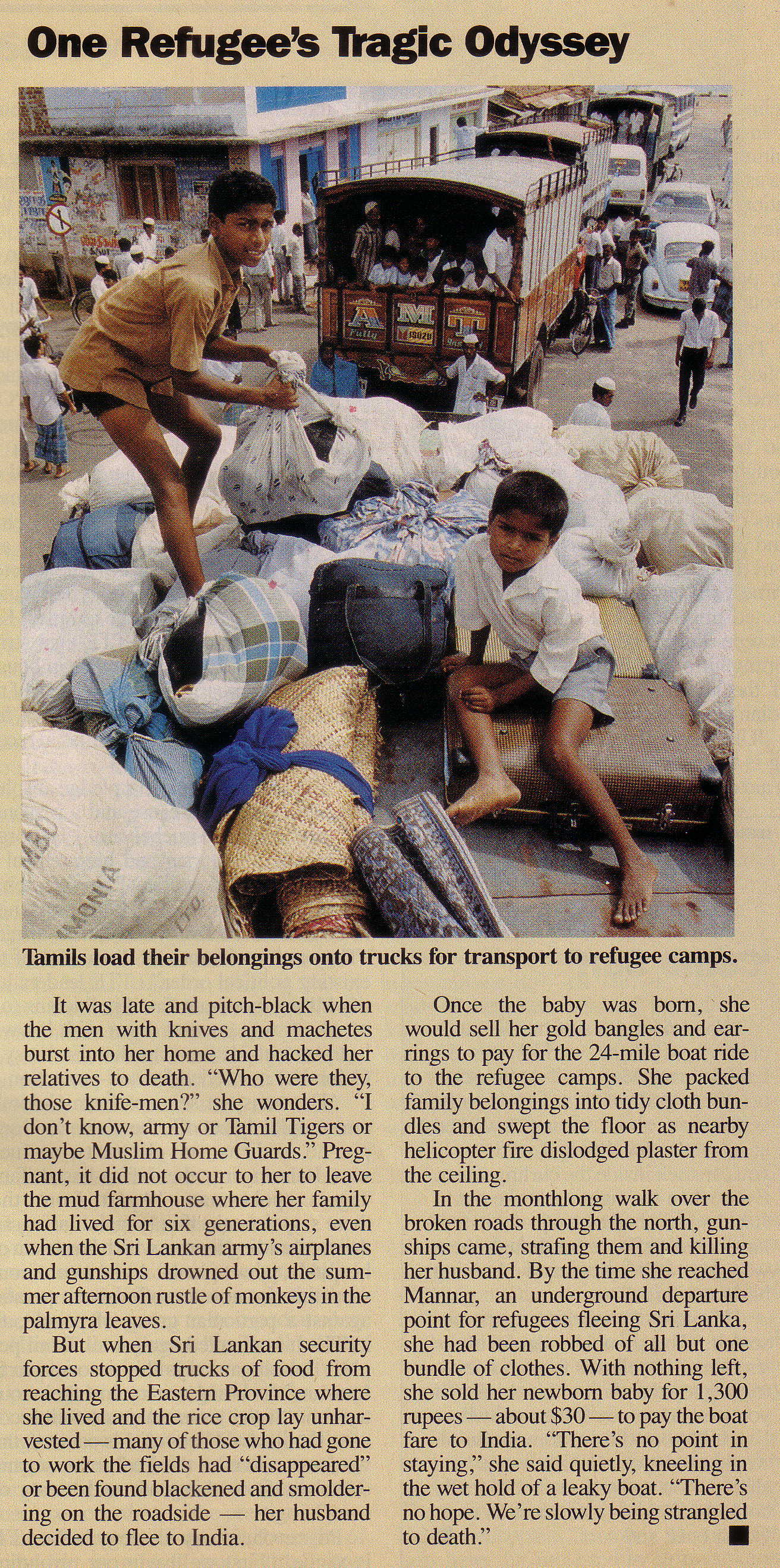

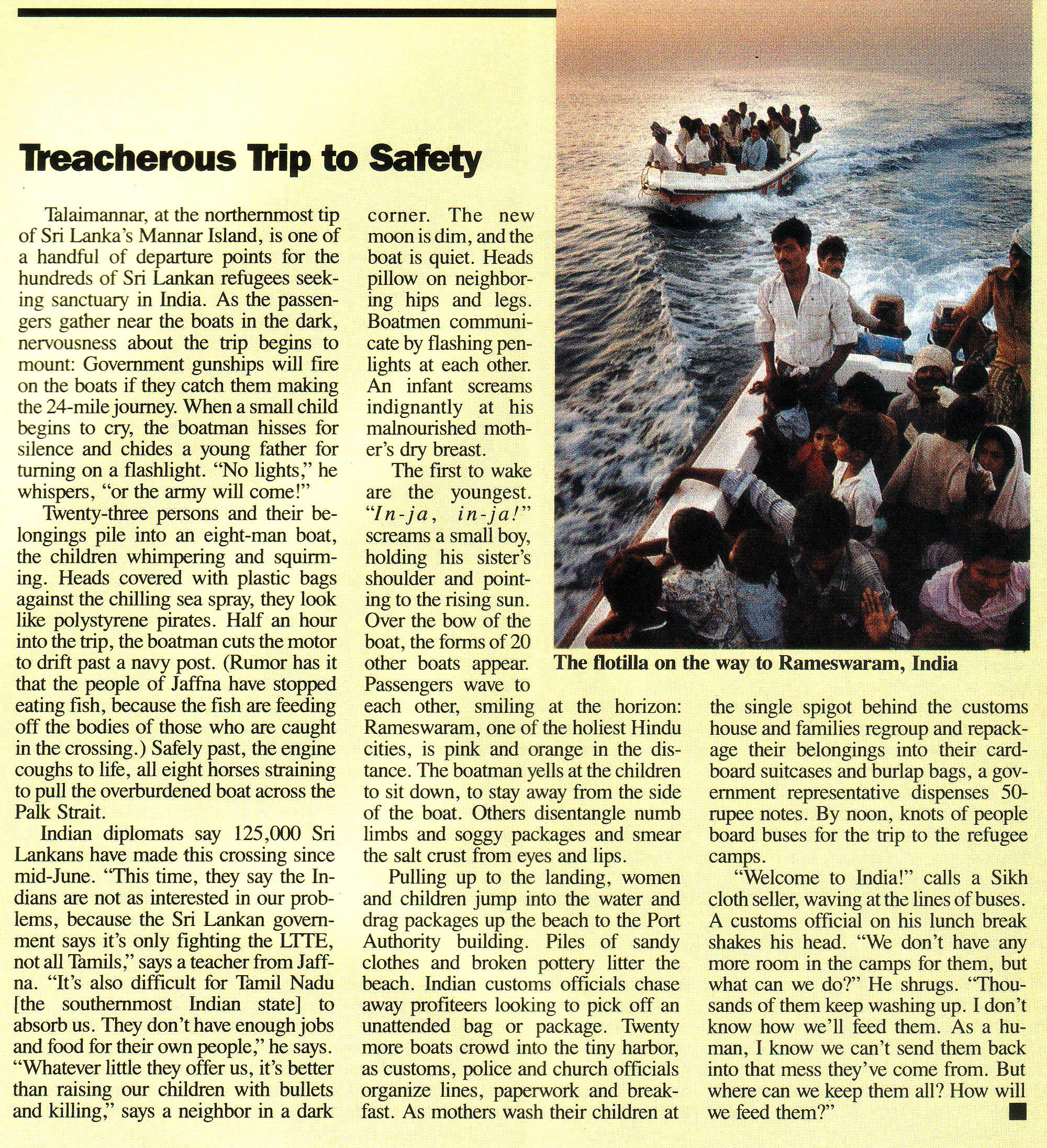

A nervous government official in Colombo admits that starvation and famine in the North are due to the security forces’ refusal to allow trucks of food, fuel and agricultural and medical supplies to pass through army roadblocks. Indian officials are anxious about Sri Lanka’s seemingly endless stream of refugees from war and hunger – as many as 125,000 since June 11 – who make the perilous ocean journey to refugee camps in India. The camps are full, the Indians say, but 1,000 to 2,000 Sri Lankans come ashore each morning.

In the North, Maj. Lal Weerakoon, the Sri Lankan army officer commanding the Vavuniya checkpoint, explains the ferocity of the fighting matter-of-factly. ‘You see, the world attention is on the Gulf now, and India is preoccupied with its own troubles. It’s our opportunity to flatten these johnnies, so they’ll never raise their heads again.’ He looks at the overcast sky and the vista of leaning palms that travel agents conjure to promote this lush vacation island. ‘The monsoon is coming now in the north, and we hope to drive the Tamil militants into the jungles, where at least half of them will die of malaria and starvation.’

The Cost of War

The cost of the Sri Lankan war machine is leeching the island’s budget and raising concerns among foreign lenders. The World Bank’s Sept. 17 report of world development indicators notes with concern the need to address long-term development issues in Sri Lanka and other low-income Asian countries. Sri Lanka’s ‘macrostability needs to be quickly ensured,’ according to the report, which points to the island’s increasing fiscal deficit of 15 percent of 1989 gross domestic product.

The high price tag of war to the death could not have come at a worse time for a small country dependent upon export of tropical commodities. Postcolonial economies generally depend on the purchasing power of their exported commodities – tea, rubber, coconut and edible oils in Sri Lanka. The Gulf crisis has thrown a wrench in Sri Lanka’s exports, as Iraq is the second-largest consumer of the country’s export-quality tea.

When the United Nations announced the embargo of food exports to Iraq, Ranjan Wijeratne, in his dual role of minister of plantations and minister of defense, told the world body that embargoes were fine for wealthy nations, but his country needed the income from Iraq’s tea trade and intended to continue exports unless the Untied Nations would pay for his losses. Three days after his display of defiance, a chastened Wijeratne announced that he had changed his mind.

An unstable Gulf situation has compounded the strapped country’s problems by impounding the funds of the 100,000 Sri Lankans who work in Iraq or Kuwait and send a large part of their paychecks home. Remittances from abroad contribute to much of the country’s income. The Kuwaiti dinar’s plunge has devalued many expatriate wage earner’s savings, and the instability of both Iraqi and Kuwaiti banks has left workers unable to transfer even the meagre remains of their accounts. The coast of transporting Sri Lankan citizens from the unsettled areas has been largely underwritten by other countries, but the untold cost of absorbing up to 100,000 unemployed will be significant.

Absorbing the expatriates is sure to place an additional strain on the social fabric of Sri Lanka. ‘The biggest problem in this country is jealousy,’ says B.N. Jayasekera, a dry goods merchant in Habarane, in the North Central Province. ‘My brother sees I have something new, he gets jealous. The Tamils see something the Sinhalese have, they want it, and vice versa. Many people will hate the returning workers because they chased after the money in the Gulf while we stayed here through the fighting. It’s all jealousy.’

Sri Lanka is certainly envious of the recent economic success of its neighbors. While Malaysia, South Korea, Thailand, the Philippines and Indonesia have generated impressive growth and even Pan-Asian investment, Sri Lanka has lagged behind. The continuing antigovernment activity and associated military spending have diverted funds sorely needed for upgrading infrastructure to meet investors’ requirements. Although the country has opened three tax-free business zones, takers have been understandably reluctant to locate capital equipment in a nation with volatile politics.

There may also be geopolitical limitations on the economy’s growth. ‘Do you think we would allow Sri Lanka to become the next Hong Kong, right in front of our noses?’ asks an Indian diplomat. It is a sore point, the superior performance of neighboring market-driven or capitalist economies over India’s planned economy. With the Soviet Union double-clutching into a market economy, its ability to be as generous a patron of India is on the wane. The V.P. Singh government’s nascent trade growth policy and the economic necessity of increasing exports creates a need for markets in which to sell Indian goods. India is not above bullying its neighbors over such perceived economic intrusions. A related dispute led to India’s closing its border with Nepal earlier this year.

Ultimately, however, a failure of vision may lie behind Sri Lanka’s failure to grow out of its gangly, tropical commodity-dependent economy. The isolation of the Colombo-dwelling bureaucrats from the problems in the North and East (and those beginning again in the South) comes to light in their hope that renewed tourism will restore the tropical resort to its tour brochure image, where happy boatmen sail the Portuguese ancestors of the modern catamaran across a peaceful, palm-fringed beach. Europeans in beachwear sip cocktails. It is a public relations campaign that has convinced its creators.

Colombo residents discuss the North and East as if they were distant countries. In early August, Sinhalese and tourists travel to the Sinhalese heartland of Kandy to attend the Festival of the Great Tooth, an enormous parade of elephants, fire dancers and drummers, all celebrating the relic of the tooth, supposedly one of Buddha’s. ‘No matter what happens – wars, storms, anything – the festival must take place,’ says the barman of a mostly empty five-star hotel. ‘The people beliee it must happen or the gods will be angered.’ As the army launched into its late summer offensive against the rebels in the North, the big story in the daily newspapers was the government’s decision to revoke a hotel-building moratorium.

Tourism peaked in 1983, with the arrival of 337,000, before publicity about the island’s fighting drove the numbers down to one-third of that total. Colombo travel agents say the story is true, the one about the German couple whose vacation in the South was ruined when a charred corpse washed up at the edge of their beach towels. Even so, the director of research for the Ministry of Commerce and Tourism can say, ‘All we need is more tourists, then the problems would be gone.’ A Tamil servant places teacups before the guests and, unsmiling, bows and walks backward out of the room.

Meanwhile, both sides say they will continue fighting. ‘As a weak government, with a weak economy, with the emerging international crisis in the Gulf, I don’t think they can afford to keep up this war,’ says LTTE spokesman Balasingam. ‘Very soon they will realize that their military option is going to be a disaster, and then they might change their attitude. If they do, and opt for political negotiations, then we’ll negotiate. So it’s up to them to make the choice: dialogue or a perpetual war.’

‘You can’t talk to the LTTE until they are convinced that they have no military option, until they know that fighting won’t get them what they want,’ says former Defense Minister Athulathmudali from his gracious home on Colombo’s Flower Lane. A handful of humorless armed men stand guard over the entrance, the waiting room, the garage, the garden, protecting the minister, who was seriously injured by a grenade explosion in Parliament two years earlier. ‘It’s just too easy to pick up a gun,’ he says.

Among those toting guns on the Eastern battlefield, Lt. Jayeasekera of 2nd Sinha Division prepares his command for an operation on the villages surrounding Batticaloa. A line of South African tanks rev up as guns from Singapore and Pakistan are locked and loaded. ‘I have fought from 1983, both North and South, and have been injured 42 times,’ the lieutenant says proudly, pointing to the shiny webbing of scars on his hands and arms. Although he blusters at first, he admits that his opponents are a tough lot. ‘Will the LTTE lose? I don’t know, they also have a dream. They also have a plan. It’s like two trains on a collision course,’ he says, motioning with those chewed-up hands. ‘They both keep going.’

**********