Untouchable Women Create the World

Untouchable Women Create the World

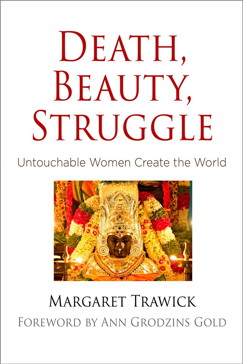

by Margaret Trawick, University of Press, 2017

304 pages | 6 x 9

Cloth 2017 | ISBN 9780812249057 | $75.00s | Outside the Americas £62.00

Ebook editions are available from selected online vendors

“This is the work of the most important anthropologist working in South India and Tamil-speaking Sri Lanka in the past fifty years.”—Martha Ann Selby, University of Texas at Austin”This book displays the full range of Trawick’s ethnographic artistry: her acute attentiveness to feelings, to linguistic nuances, to fragile bonds, to fierce commitments, to the ways lyrical composition and storytelling articulate otherwise suppressed struggles.”—Ann Grodzins Gold, from the Foreword

Death, Beauty, Struggle represents a long labor of love and the summation of forty years of Margaret Trawick’s groundbreaking research. Centering her gaze on the lowest castes of India, now called Dalits, she describes the experience of women at this precarious level who are still treated as sub-human, sometimes by family members, sometimes by higher-caste men. Their private worlds, however, are full of art; rural Dalit women sing beautiful songs of their own making and tell remarkable narratives of their own lives.

Much that Tamil women shared with Trawick is rooted in the passionate attachments and acute wounds generated within families, but these women’s voices resonate well beyond individually circumscribed lives. In their songs and life stories they critique social, political, economic, and domestic oppressions. They also incorporate visions of natural beauty and immanent divinity. Trawick presents Tamil women’s words as relevant to universal human themes.

Trawick’s frames of analysis, developed throughout her long career of fieldwork in India, inform her ethnography of expressive culture. The songs and stories of Dalit women were recorded and transcribed, to be translated into lyrical passages in her own work. Death, Beauty, Struggle demonstrates a conviction that persons without privilege—from the rape victim to the landless laborer—possess both power and agency. Through verbal arts, Dalit women produce not only acute cultural critiques but also astonishing beauty.

Margaret Trawick is Professor of Social Anthropology Emerita, Massey University, New Zealand.

Table of Contents

Foreword, by Ann Grodzins Gold

Preface

Introduction

Chapter 1. Ma�riamman

Chapter 2. Sorrow and Protest

Chapter 3. Work and Love

Chapter 4. On the Edge of the Wild

Chapter 5. The Life of Sevi

Chapter 6. The Song of Si?gamma�

Conclusion

Notes

Glossary of Tamil Words and Phrases

References

Index

Acknowledgments

Excerpt [uncorrected, not for citation]

Foreword

Ann Grodzins Gold

Margaret Trawick’s writings on Tamil women’s songs and lives offer rare and intimate glimpses into kinship, myth, work, want, anger, reverence, and more. Revealing a subtle, never static, interplay between abjection and empowerment, this book testifies that human beings, low born and ill-treated within a punishing social system, neither acquiesce to fate nor simply rail against it, but may indeed radically rethink the world. And I stress that it is absolutely the world being rethought: not their world, but ours too.

Much that Tamil women shared with Trawick is rooted in the passionate attachments and acute wounds generated within families, but these women’s voices resonate well beyond individually circumscribed lives. In their songs and life histories they critique social, political, economic, and domestic oppressions. They also incorporate visions of natural beauty and immanent divinity. Trawick presents Tamil women’s words as relevant to universal human themes. She never hesitates to put high social theory in conversation with observations and assessments made by unschooled and often impoverished women, and thereby shows deftly how each body of thought may enlighten the other. Much of Trawick’s work has at its center her gifted rendering of vernacular Tamil oral performances into an English that profoundly affects the heart.

Trawick’s fieldwork in India and in Sri Lanka resulted in two monographs: Notes on Love in a Tamil Family (1990) and Enemy Lines: Warfare, Childhood, and Play in Batticaloa(2007). Now she offers an ethnographically grounded book on women’s expressive traditions. Untouchable Women Rethink the World contains an original vision of gendered lives, poetry, devotion, and social hierarchy in Tamil Nadu. This book displays the full range of Trawick’s ethnographic artistry: her acute attentiveness to feelings, to linguistic nuances, to fragile bonds, to fierce commitments, to the ways lyrical composition and storytelling articulate otherwise suppressed struggles.

If most of the fieldwork on which this book is based was conducted during the last two decades of the twentieth century, Trawick is reporting on conditions that have been slow to change, and her interventions are timely. Introducing a recent anthology of Tamil Dalit writings (all from literate authors, among whom approximately 20 percent are female), the coeditors write, “numerous bits of evidence show that even before the birth of the word ‘Dalit’, there was a recorded history of the ‘untouchables” fight against discrimination and literary expressions that spoke about it. A turn towards this recovered history of the region may help alter our vision of Dalit literature” (Ravikumar and Azhagarasan 2012, xv). While their volume contains a rich range of important and moving material, there is exactly nothing in it from oral traditions. Work such as Trawick’s furthers the project of recovering regional history by bringing to the page eloquent voices from unwritten sources.

These chapters shed all kinds of light, providing a shifting radiance: sometimes flaming, sometimes flickering; sometimes glaring, sometimes soft. It is full-spectrum light. My foreword points to just four thematic elements in Trawick’s book, considering each as a filament, each possessing a special glow, each at times delivering bright flashes. The light metaphor with which I am playing came to me unbidden, but I allowed it to proliferate, not merely for its versatility, but because the metaphor of “darkness” has been used by some authors—recently in Aravind Adiga’s best-selling novel The White Tiger—to characterize, or in Adiga’s case to caricature, rural India. Thus “The Darkness” with its erratic or nil electricity, its lagging literacy rates, its political impotence, its cherished livestock, is posed in stark contrast to the middle-class ideal of “India shining.”

If I may indulge in a bit more metaphoric play, let me say that these variegated lights in Trawick’s chapters might also be likened to many alternative sources of light devised and employed in areas sporadically short on current as is much of rural South Asia. In our power-glutted world we fail to realize how many kinds of light can be tapped in times of need: candles, oil wicks, pressure lamps, torches both oil-soaked and battery powered, and lately the light from mobile phone screens. There is also moonlight, and even the fireworks that go “bang! boom!” (Chapter 4). Rural arts of improvisation, in lighting and many other areas, give the lie—as do Trawick’s essays—to diminished views such as Adiga’s of benighted country folk.

Following the introduction, Trawick’s six central chapters present to readers vocally powerful female beings whose identities may be goddess, priestess, singer, or ambiguously merged and shifting combinations of these. The four filaments I highlight crosscut chapters, although some are particularly evident in one or another. These are gender and social justice; intertwined emotions and ecologies; interpenetration of divine and mortal biographies, and an unrepentant anthropology.

Gender and Social Justice

Then, as the song goes, Si?gamma�, having emerged from within the house, “rising up high, speaking with unsheathed energy, wearing pearls,” addresses her lame older brother. . . . She leaves the house, she goes outside, they raise her up. (Chapter 6)

Gender and social justice, or injustice as is more often the case, painfully intertwine throughout almost every passage of Trawick’s work but may be most vividly explicit in the tale of Si?gamma�’s life as girl and goddess. Si?gamma� was an untouchable girl, raped and murdered. She emerges as a goddess from prison-like confinement as described in the above excerpt. That she is wearing pearls is meaningful. Of course it is a poetic convention to praise deities as decked in gorgeous and costly items. But in Si?gammā’s terrible and wonderful story, such celebration of a no longer vulnerable female beauty has extraordinary impact. Like the young woman renamed by the Indian press “Delhi Braveheart” in 2013, Si?gammā bears painful testimony against gang rape, leaving behind not just a mutilated corpse but a transformative legacy of witness.

Ghanshyam Shah and colleagues (2006) present a twenty-first-century investigation of “the extent and incidence of untouchability in different spheres of life in contemporary rural India.” Their team covered 565 villages across eleven states including Tamil Nadu, where Trawick worked. They concluded: “Untouchability is a practice that profoundly affects the lives and psyches of millions of Indians. . . . Despite the abolition of untouchability by the Constitution of India, and despite the passage of numerous legislations classifying untouchability in any sphere as a cognizable criminal offence, . . . the practice lives on and even takes on new idioms” (2006, 164). The authors of this sobering study also note, unsurprisingly, “the particular double burden borne by Dalit women, for whom gender and caste combine to create greater vulnerability to social exploitation and oppression” (2006, 165).

Trawick makes her readers fully cognizant of women’s double burden. She also teaches us that such burdened women have capabilities to escape their confines imaginatively, and that at times they emerge like Si?gammā with unsheathed energy. Some of the women whose voices readers encounter in Trawick’s essays have charted truly alternative destinies whether as healer, teacher, or social activist. The majority live their daily lives compliant with a system that denies them value and power, maybe even humanity. But that system does not capture them, as their songs and stories available here show clearly.

In one unusual comical song critiquing European male authority, the singer’s words are most explicitly fierce and rude. As Trawick puts it, “No punches are pulled” (Chapter 4). The singer describes a man sitting “idly on his porch,” clueless because he “doesn’t know any Tamil.” She urges her companions: “Piss into his pot, girl. Pour it into his rosy red mouth.” The foreigner’s ignorance of Tamil surely makes him a safe object of derision in Tamil. It is more perilous to deride internal oppressors, whether male family members or high-caste predators. Toward such persons, women generally lodge aggressive complaints using more oblique language, and more elaborate poetic conceits.

Politicized, literate Dalit voices are loud and strong in the public arena, and no anthropologist is required to convince others of their active resistance and outrage. The precious understanding that Trawick offers is an inner core of refusal to accept degradation among persons who are not activists, who are not mobilized, yet who vocally indict the socioreligious system that continues to hurt them. These voices speak and sing with shattering eloquence about injustice, about suffering, about pain. They also reveal embodied lives where moments of beauty, hope, and affection are cherished. Their identities are not defined solely by those who scorn, shun, abuse, exploit or even murder them. Justified anger is there, but so is delight—delight in something as simple as a bar of soap, something as deep as a quest for spiritual truth. This is true dominance without hegemony (Guha 1997). Trawick’s particular genius is her ability to convince us of this and to inspire her readers by showing these women’s courage, fortitude, integrity and ability to turn sorrows and trials into art.

Intertwined Emotions and Ecologies

Today clusters and clusters of eggplants,

O poor girls, though they fruit on the vine,

With no one to hold and embrace us, no one to hold and embrace us,

We rot with the vine, mother. (Chapter 2)

A vine laden with shiny purple eggplants is a welcome image of abundance, food, and fertility. To rot on the vine should not be its fate. In this crying song the verbal imagery of rotting annihilates a healthy source of nourishment, transforming it from plenty to waste. As Trawick explicates this and other verses, the song is about “ineffective containment, containment that offers no fulfillment, completion, or protection” (Chapter 2).

I marvel at this song’s simultaneous evocation of lushness and deprivation. It is only one verse of a very sad song, and the song is not just about neglect. It is also about justice, in the family as well as in the community. It is only one song among many equally deep and compelling in their musical intervention in a world often deaf to the suffering of the lowborn and of women. The songs’ organic imagery fluidly unites human and other forms of life.

Trawick’s translations, of which the eggplant verse offers just a single glimpse, evoke an intertwined universe of plant life and human feelings as they permeate one another. This is a truly human ecology. Other scholars of classical South Indian literatures attest to similar resonance across species and landscapes. In Tamil poetics, as A. K. Ramanujan expressed it, there exists “a taxonomy of landscapes, flora and fauna, and of emotions—an ecosystem of which a man’s activities and feelings are a part” (1990, 50). More recently, Martha Selby, a scholar and translator of Tamil literature, offers additional observations that complicate the poetic meshing of humans with environments. She writes that “in early Tamil poetry, it is not nature—that ‘something out there’—that is the object of the human impulse to tame, rather human emotion and sexuality are the objects of capture and ordering; not nature, not the wild outside but the wild within, disciplined with networks of referents, symbols, and indices culled from the environment.” Selby asks, “What does it mean to assign plant and animal natures to human beings?” (2011, 14). In Trawick’s translations of the songs sung by day laborers, by rat catchers, by gypsy-like scavengers and hunters, there are similarly delicate, evocative, and complex visions of the “wild within.”

Interpenetration of Divine and Mortal Biographies

Sarasvati, through taped interviews as well as through conversations, showed me something I had never thought of before, which was that the woman and the spirit she worshipped had been through similar life experiences, in particular, problems with men. Māriamman was, then, a model of what Sarasvati experienced herself to be, and was struggling with Sarasvati, forcing her, to do what Māriamman in her life story had finally achieved. (Chapter 1)

In a compelling portrait of the priestess Sarasvati and the goddess Māriamman, Trawick shows us in Chapter 1 how closely intertwined the life stories of deity and devotee can be. Māriamman even grants Trawick, the young American anthropologist, an interview, speaking through the possessed body of her mortal medium. Māriamman literally rules Sarasvati’s life in that she presents her with rules that must be followed. But she also endows her human vehicle with a financial and emotional stability that the priestess had not known in her life’s struggles before her own being became so thoroughly intertwined with that of the mother goddess. In Sarasvati’s case, however counterintuitive, to be possessed is to be, if not liberated, then at least relieved of some daunting hardships. It also enables her to help others deal with their own difficulties in life.

In Chapter 4, a woman with tuberculosis whose name is Kanyamma�, which is also the name of a local goddess, sings songs about that goddess. She laments the goddess’s decline, equated with environmental decline. Kanyamma� the woman also sings of the attractive power of the virgin goddess in the form of a girl wearing flowers in her hair. Their fragrance is irresistible, a botanical source of divine as well as human allure (for Tamil women customarily wear fresh flowers in their hair). Trawick concludes about one of Kanyamma�’s songs that it suggests “a place where a woman is on top” (Chapter 4). That place is on the edge of the village settlement. In many rural South Indian communities, goddesses are regularly enshrined a bit beyond human habitations, a bit apart from the messy and imperfect human world. The exception of course is when they choose to enter someone’s body as was the case with Māriamman, who possessed the priestess Sarasvati and intervened in hers and many others’ everyday lives to alleviate their sufferings.

Unrepentant Anthropology

During one of my unpolluted spells I went to visit Chandra, and I found that she was now observing her time of impurity, so I went out back to where she was staying. we had been sitting alone together for some time when suddenly—defying the Brahminical rule which demands that during her menstrual period a woman shall touch no one—Chandra grabbed my hand, tightly, saying nothing.Our friendship intensified at that moment, and I realized that this too was a great source of śakti. (Trawick [Egnor] 1980, 28)

The words with which I epitomize my closing filament come not from this book but from Trawick’s earliest publication (1980). They evoke for me the intimacy, the connection, the embodiedness at the heart of Trawick’s anthropology and of Death, Beauty, Struggle.

Rather than a disembodied authorial voice, Trawick gives us presence—her own thoroughly embodied presence. Among observant high-caste South Indian Hindu families menstrual taboos would cause a woman literally to be “not in the house” monthly. Trawick as a good participant observer was trying to live by the same rules as her hosts. But in an unexpected place she encountered transgression, and here she celebrates it. In a way, inspired by her Tamil friend, Trawick breaks disciplinary taboos, speaking of her own bodily processes and acknowledging in her friend’s cross-cultural gesture that the presence of an anthropologist sometimes opens up a space for countercurrents in a cultural universe. In 1981, when I was just back from my doctoral fieldwork, it was genuinely momentous to encounter in Trawick’s published anthropology such a strong human voice, true to her lived experience. For me fieldwork had never been about gathering and analyzing data but rather about forging relationships. Reading Trawick enabled me to acknowledge this in my own writing.

Trawick’s anthropology never apologizes for its humanity, its unabashed incorporation of anthropologist as person into the text, sometimes recursively as when Kanyamma� sings about Trawick:

When they see you, desire takes hold.

When they see you, desire takes hold.

When one sees the West, it seems very far away.

It comes bearing thunder and lightning.

When one sees the West, it seems very far away.

It comes bearing thunder and lightning. (Chapter 4)

Commenting on these lines, Trawick writes, “Just as thunder and lightning coming from the faraway West must have been seen as fearsomely powerful, and capable of boding great good or great ill, so perhaps I was perceived. Although I just wanted to be a normal person there and melt into the everyday life of the village, that was not possible” (Chapter 4). Here she speaks for quite a few anthropologists perpetually chagrined by their proverbial sore thumb outsider status, by a desire for affirmed if ineffable belonging, by the burden of too many visibly attractive material belongings.

Trawick’s anthropology demonstrates a conviction that persons without privilege—from the menstruating woman isolated in her hut, to the rape victim, to the gypsy peddler, to the landless laborer—possess both power and agency. Through verbal arts oppressed persons produce acute cultural critiques and also beauty. Trawick simply assumes these are persons worth hearing, that their words are worth the labor of a loving translation and that they have much to teach us. Such assumptions might be the purported stock in trade of our beloved, maligned anthropology, but they are rarely put into practice with such a delicate mix of humility and eloquence as that offered in Trawick’s writings.

For the 2012 annual meeting of the American Anthropological Association I organized a panel honoring Trawick’s contributions. Lawrence Cohen’s paper used appropriately enigmatic poetic language to characterize Trawick’s work, speaking of her “demonic rigor” and asserting that her writing is “asli” (Hindi, ‘real’), in that she “crosses the line into a space marked by beauty but also hurt, chaos, and indeed death.” One discussant, Anand Pandian, spoke of “the liquid appeal of that anthropological imagination that Trawick’s work encourages us to exercise.” He likens this “liquid appeal” to an attitude he learned from his grandfather, who would speak of his lack of fear under many trying circumstances including drinking water from dirty ditches: “What I learned, listening to my grandfather, is that there is health, as well as danger, in breaching the boundaries of the self” (Pandian 2012; see also Pandian and Mariappan 2014).

Prompted by these appreciations, I slip, in conclusion, from a trope of light to one of liquid. I urge readers of this wonderful book to sip or gulp from the real, demonic, transgressive fount of Margaret Trawick’s anthropology and the voices of South Indian women transmitted here. I hope readers will imbibe with these healthy draughts the energy to cross the lines and breach the boundaries, in modes that are not invasive but incorporative.

Preface

The fieldwork that resulted in this book was done intermittently from 1975 to 1991 while I was engaged in other projects in Tamil Nadu. The study for the book and the writing of it has been done continuously until now. Emergent from this work has been, among other things, a picture of how the government of India, and the British colonial government before it, tried to freeze groups of people in particular times, places, and occupations. Some are categorized as “Backward.” Others categorize themselves as “Forward.” Others are considered untouchable and categorized as “Scheduled Castes” or “Scheduled Tribes.” All the castes are ranked against each other. This ranking developed in parts of India millennia ago through a long and slow process. But real time has disrupted such categories. What has changed quickly, what has changed slowly, how the life of one or another person or group has been broken by change, how one or another person or group has adapted to change, how valuable the work of memory is, and how damaging old moralities are—these are realities unsought but uncovered in this book.

Anthropology, my chosen discipline, the study of humanity, has a long history and has been through many changes, from ancient days until now. This book presents bits of that history in India, from poems and organized treatises created millennia ago, to accounts from the nineteenth century, to ethnography from the late twentieth century, to articles and books from the twenty-first. Some of these have been created by Tamil people who did not think in terms of anthropology or history but more in terms of poetry and song. Later works have been composed by journalists, authors, filmmakers, artists, poets.

Most of my life, whether in the field or reading and writing, I did not think much about caste or gender or systems of rank. All of those were boring to me. So was politics. But now I cannot avoid such topics. The focus of these chapters is not on caste and gender oppression, important as these issues are to Indian society, but on the verbal art of the oppressed. These were people I thought of as normal. This book is about human beings as they describe and express their own lives and the lives of others in narrative, song, and conversation. Although individuals are important, relationships are more so. Caste, gender, and familial relationships, though rarely mentioned in song or speech, constitute an important feature of each of these women’s lived environments. In the larger view, caste, gender, familial, religious, and ethnic hierarchies in India cannot be ignored. This book shows clearly that nonliterate people living in the most abject circumstances, women of untouchable castes, may be the intellectual equals of great scholars far away from India. Caste is not overlooked, but it is seen in this book mostly through Dalit women’s eyes, or more precisely, through the voices of Dalit women.