by Tamil Guardian, London, October 13, 2019

Former UN staffer Benjamin Dix released his first graphic novel this month, exploring the story of Tamil families trapped in the Vanni in 2009, as the Sri Lankan military launches an ominous offensive that kills tens of thousands civilians.

The Vanni, based on interviews that Dix carried out with Tamils across the globe, is a truly heartbreaking piece.

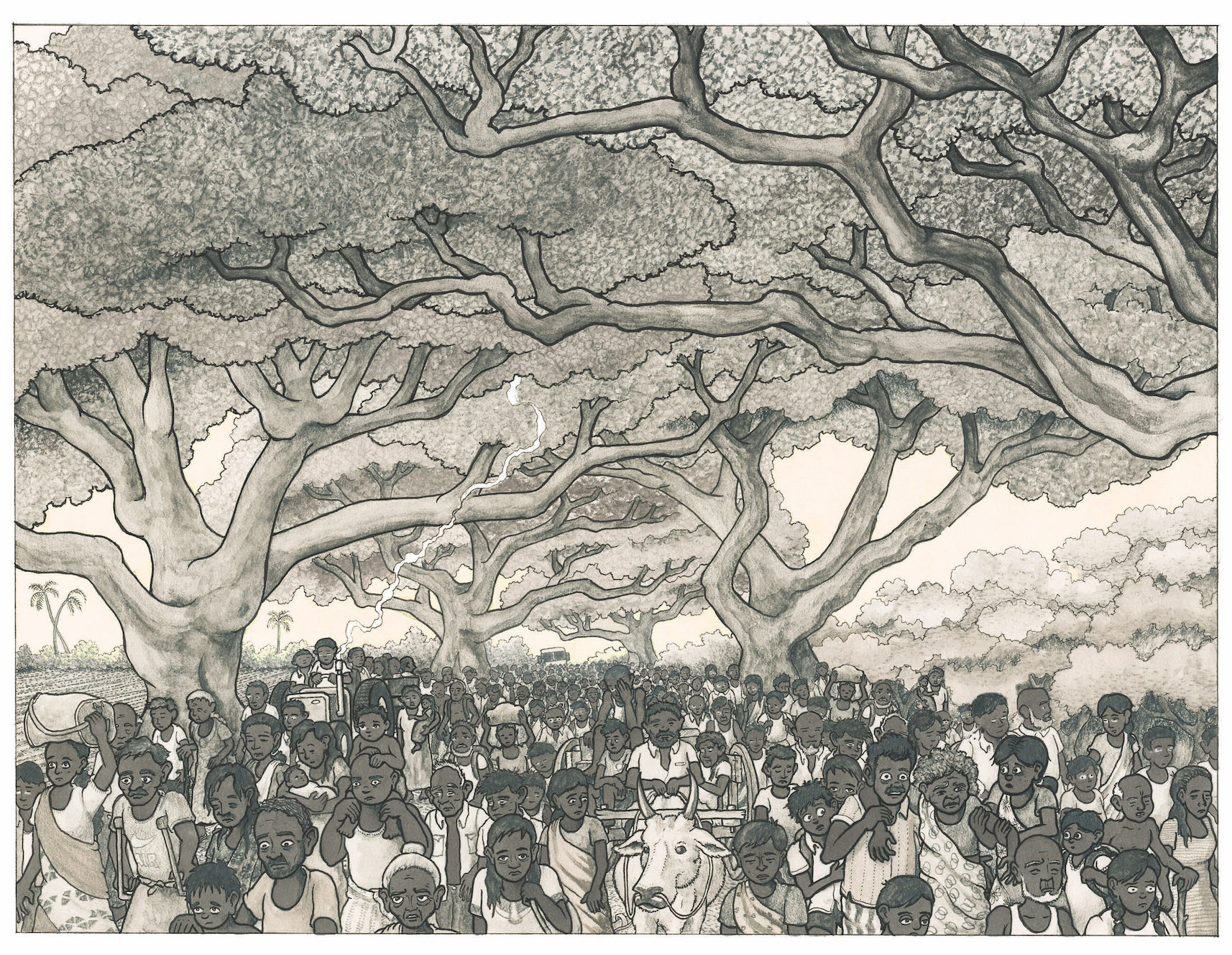

Authored by Dix and with the powerful illustrations of Lindsay Pollock, it makes for compelling reading. Written in a comic book style, the dialogue between characters throughout the piece is short but hard hitting. From the opening scene in London where protagonist Antoni – a Mullivaikkal survivor and East London taxi driver – is unwittingly asked by his patrons about the beachside resorts and cocktails of Sri Lanka, to the haunting almost-single word conversations that Tamils trapped in the No Fire Zones share as they shelter from artillery fire, every word is delivered with force.

Though the characters have been fictionalised, the stories are very real says Dix. “They are the amalgamation of many, many interviews with Tamil civilians, ex-Tigers, Sri Lanka experts, people who myself personally and Lindsay have gone and interviewed about their experiences,” he told the Tamil Guardian in an interview last week.

Much of the strength of these testimonies lies in the Pollock’s illustrations, which at times capture the range of emotions more poignantly than words. The artwork, which is monochrome in style, is intricately laid out across the pages, from smaller, faster moving panels to bigger full page illustrations, which almost silently capture the enormity of destruction that took place. A lot of the interaction between characters and the weight of the turmoil they undergo is portrayed in the artwork. Indeed, some of the novel’s hardest hitting scenes take place where there is no dialogue, simply speechless tragedy.

Though the book is a graphic novel, it does not shy away from showcasing the horrors of that final phase of armed conflict. Incidents of sexual violence and summary executions committed by Sri Lankan troops are deftly showcased, with the illustrations capturing the horrific nature of the crimes without having to go into gruesome detail.

As Dix notes in the afterword of the novel, the grim events of Mullivaikkal continue to have lasting effects to this day. The struggle that survivors continue to go through from the camps of Menik Farm to fleeing and seeking asylum abroad in a country where they may not even speak the native language, are also extensively covered. The fact that to this day, those responsible for the horrific acts described walk free whilst survivors are still struggling for a safe home, makes the novel even more crucial in capturing the reality that Tamils around the world continue to endure.

“The story of the 2009 war in Sri Lanka in which tens of thousands of Tamil civilians were brazenly and brutally killed, is rapidly being buried by powerful countries with strategic and business interests in the region,” said Arundhati Roy in her review of the book. “This book seeks to unbury those terrible, sordid secrets and place them in clear view for the world to see.”

Though stories from Tamil survivors have been retold in a range of formats – from United Nations reports to visual documentaries and songs – Dix is the first to put them in an English language comic-book style graphic novel. In doing so, it does gloss over some of the greater political machinations that led to the massacres at Mullivaikkal. The Sri Lankan military’s repeated targeted shelling of civilians sheltering in the No Fire Zone, including of hospitals that had relayed their GPS co-ordinates, could have been more explicitly laid out. And Colombo’s constant rejection of calls for a ceasefire, for instance, were missed altogether.

The deep and complex relationship the Tamil community has with the LTTE and the armed struggle is also alluded to throughout the book, but it was not explored or laid out in great detail. The novel touches on difficult issues in that relationship, such as reports of forced recruitment which Dix fiercely criticises. Though it acknowledges that the movement was very much embedded within the population of the Vanni, it is not described enough and leaves for wanting when it comes to the politics of resistance movements combatting state oppression.

Nevertheless, it does not detract from the raw emotion in the novel, which makes it a truly engaging retelling of the struggles that the Tamil people faced, as well as a testament to the unyielding spirit of survivors, both in the Vanni and around the world. The book is an essential read for a wide audience, from human rights advocates and policy makers, right through to casual tourists who are considering Sri Lanka as their next holiday destination. At a time when there has been virtually no progress on accountability for the crimes in the Vanni, ongoing militarisation of the region, continued torture and a raft of other rights violations, Dix and Pollock have masterfully showcased that in many ways the suffering for survivors is far from over.

The Vanni is available to buy from Amazon here. [or here in the US]

See more from Positive Negatives here.