by T. Sabaratnam, December 31, 2003

Volume 1, Chapter 23

Original index of series|

DDC Elections

President Jayewardene wanted to show the world, through the District Development Council election of 4 June 1981, that the majority of the Tamils did not approve the separate state which the TULF was demanding. He succeeded in showing just the reverse.

The DDC election was held countrywide, but the main focus was in Jaffna because the real drama was enacted there. In the Sinhala south it was a lackluster election since the opposition Sri Lanka Freedom Party boycotted it. That made it plain sailing for the UNP, which swept all the 18 Sinhala majority districts.

In the northeastern province it was a different tale. The UNP snatched only Ampara district, one of the seven districts in that province. In Amparai Muslims constitute the majority with 41% of the population and Sinhalese come second with 37%. Tamils, on whose vote bank the TULF depend, form only 20 percent of the population of Ampara. The TULF naturally lost Amparai, but won the other six districts.

In the Trincomalee district where Tamils comprise only 33.9% of the population, Sinhalese 33% and Muslims, 29%, the TULF polled 44,692 votes to the UNP’s 42,388. In the other eastern district of Batticoloa where Tamils constitute a clear majority with 70% of the population, Muslims 24% and Sinhalese 3%, the TULF won the election and captured the council.

The TULF swept all the five districts in the Northern Province- Jaffna, Kilinochchi, Mannar, Vavuniya and Mullaitivu.

Overall, Jayewardene helped the TULF to reaffirm the mandate it obtained in the 1977 parliamentary election; that Sri Lankan Tamils living in the northeast supported a separate state, a fact which he wanted to disprove.

Overall, Jayewardene helped the TULF to reaffirm the mandate it obtained in the 1977 parliamentary election; that Sri Lankan Tamils living in the northeast supported a separate state, a fact which he wanted to disprove.

Jayewardene also wanted to weaken the TULF politically and strengthen alternate Tamil groups which could be managed

www.tamilarangam.net jkpo;j; Njrpa Mtzr; Rtbfs;and persuaded to accept whatever he would give as the solution to the Tamil problem.

It had become necessary for Jayawardene to grant some sort of autonomy to the Tamil regions to silence the international

community, especially aid givers, who had begun to make ‘noises’ in support of meeting the aspirations of the Tamil people. Showing to the world that he was prepared to meet the aspirations of the Tamil people, at least to some extent, was the prime objective for which Jayewardene “cooked up” his District Development Scheme. The UNP, in its election manifesto for the 1977 parliamentary election, gave two promises to the Tamils to win over their votes in Southern Lanka.

The UNP promised to take action to remove Tamil grievances, which it identified as being in the fields of education, colonization, use of the Tamil language and employment in public and semi-public corporations and undertook to call an All-Party Conference to work out a permanent solution to the ethnic dispute. Jayewardene did take some action to give relief to the Tamils, but did not call the All-Party Conference. Keen on politically finishing off his main rival, Sirimavo Bandaranaike, Jayewardene shirked holding the All-Party Conference that could have given her an opportunity to stage a comeback into politics.

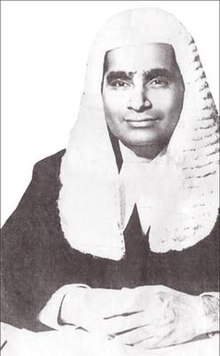

Professor Jayaratnam Wilson

Instead, Jayewardene decided to negotiate with the TULF, which had emerged the predominant voice of the Tamils in the 1977 election. He appointed two influential Tamil intellectuals, Professor Jayaratnam Wilson of the University of New Brunswick, the son-in-law of the founder of the Federal Party, S.J.V. Chelvanayakam (Thanthai Chelva), and Dr. Neelan Tiruchelvam, a jurist, son of the Federal Party’s representative in a former UNP cabinet, to handle the matter.

Wilson told me that Jayewardene looked very concerned when Jayawardene talked to him about settling the ethnic conflict.

“We cannot allow it to fester. That will endanger the very existence of the country. Now that Amirthalingam is the Leader of the Opposition and the TULF had become part of the parliamentary game, let’s get together and lay the foundation for the solution,” Jayewardene told him.

Jayewardene then spelt out the basic plan he had conceptualized. He told Wilson that they could start with the development of the district. “We’ll form an elected council for each district and make the council responsible for its

development. We would give the DDC’s the needed powers and finance,” Jayewardene added, “This is just what the Jaffna man wants. DDC would afford an opportunity for the economic development of the Tamil areas.”

Wilson and Neelan persuaded Amirthalingam and the TULF to accept the DDC scheme and Jayewardene appointed the 10- member Victor Tennakoon Presidential Commission on District Councils in 1979. Wilson and Neelan toiled hard to make it the effective first step for regional autonomy. Tennakoon and other Sinhala hardcore members of the commission frustrated their effort by making the DDCs dependent on the government and its ministers and bureaucrats. The government further diluted the DDC scheme when the bill was drafted. Wilson was disappointed with the final outcome and commented: Too little, too late.

The usual Sinhala politics was enacted when the bill went before the parliament.

The opposition Sri Lanka Freedom Party opposed it. Opposition leaders and members of the Buddhist clergy tore and burnt copies of the bill and accused Jayewardene of selling the country to the Tamils. The Buddhist clergy shouted that the DDC arrangement would lay the foundation for a Tamil separate state. Jayewardene countered that propaganda by telling a delegation of high ranking Buddhist priests that the DDCs were a general arrangement that applied to the entire country.

Then he told them the real objective of his scheme. “Once Amirthalingam and the TULF get involved in the DDC exercise they would become part of the power game,” he said. Through the DDCs Jayewardene wanted to slay the Tamil demand for a separate state. He wanted to draw the TULF and the Tamil people into the administrative process. The TULF would run some sort of glorified local administration in their areas and forget its cry for a separate state.

UNP’s Decision to Contest

President Jayewardene planned everything methodically, meticulously, craftily so that he, his government and his party would derive maximum benefit out of any plan. The DDC scheme was no exception. He wanted to weaken Amirthalingam, the TULF and the Tamil community so that he could enhance his standing and strengthen his government’s popularity among the Sinhala people and the international community. The weakening of Amirthalingam, the TULF and the Tamils was planned in two fronts. Firstly, the gulf between the TULF and the revolting Tamil youths would widen once the TULF accepted the DDC scheme. It happened. Secondly, the TULF’s bargaining position and its standing among the Tamil people and the international community would be weakened if the UNP could win one or two seats in every district in the northeast province. The UNP could then claim its decisions were representative of the entire people of the country, including Tamils. The UNP working committee discussed this matter extensively and decided to prepare the ground through a series of ministerial visits to the north. Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasa was sent first. I covered his 4-day tour. All his public meetings were well attended and he was accorded a rousing welcome in Jaffna and Point Pedro. Encouraged by Premadasa’s triumphant visit, Jayewardene sent Lalith Athulathmudali, Gamini Dissanayake and Cyril Mathew to tour the

Jaffna peninsula. I covered those visits also. Those ministers organized a network of UNP organizations in the Jaffna peninsula. Jayewardene started talking about an electoral bridgehead between the north and the south.

Close to the nomination day Jayewardene sent a group of top officials to assess the situation in Jaffna. The group advised him against the UNP contesting in Jaffna. The officials told him that most of the UNP organizers he had appointed were self-seekers and lacked popular backing. Similar advice was given by Wilson and Thondaman. But, Jayewardene decided to hold the election in Jaffna under emergency and to contest it, a disastrous miscalculation.

The UNP ran into difficulties from the start. With great difficulty it managed to compile the list of candidates. The list was headed by A. Thiyagarajah, who in the 1970 parliamentary election defeated Amirthalingam in the Vaddukoddai seat.

Then, as a popular former principal of the prestigious Karainagar Hindu College and member of the Karainagar trading community, Thiyagarajah was popular. But his term in parliament was disastrous. He deserted the Tamil Congress Party in which he contested and joined the Sirimavo Bandaranaike government and supported the 1972 constitution, which the Tamils declared “the Charter of Slavery.” PLOTE, the new militant group Uma Maheswaran formed after he was expelled from the LTTE, requested the UNP candidates to withdraw from the contest. Thiyagarajah declined. On 24 May two boys, members of the PLOTE, cycled to his jeep as he was getting into it and shot him. He died in the Jaffna Hospital. Then they killed Nadarajah, a UNP organizer.

Rigging the Election

Jayewardene decided to go ahead with his plan to capture one or two seats in the Jaffna District Council. He sent a high-powered government delegation headed by powerful ministers Gamini Dissanayake and Cyril Mathew, defence secretary Col. C. A. Dharmapala, additional defence secretary General Sepala Attygala, cabinet secretary G. V. P. Samarasinghe and Army Chief-of-Staff Brigadier Tissa Weeratunga to Jaffna, to take any “on the spot decisions” to subdue the TULF and manage Tamil militants. The UNP launched a campaign of terror and intimidation.

Over 500 policemen were sent on election duty. A special contingent of about 200 men was sent under the command of DIG Edward Gunawardene. They were stationed at Alfred Duraiappah Stadium, a stone’s throw away from the Jaffna Public Library. The rest were sent to the various police stations in Jaffna. Police was ordered to keep the peninsula clear of the militants. They launched a massive operation and detained about 30 Tamil youths. The youths were held incommunicado.

Amnesty International expressed its concern about them to Jayewardene and urged him to allow all detainees immediate access to lawyers and relatives. It also alleged that all the detainees had been tortured. Four of those detainees filed, for the first time, Habeas Corpus applications and the Appeal Court ruled that torture and ill treatment had occurred in two cases.

Subash Hotel 2020

Brigadier Tissa Weeratunga was shifted to Jaffna to take control of army operations. He took almost the same group that had worked with him in 1979. He converted Subash Hotel into army headquarters.

The Nachchimar Kovilady incident of 31 May, police retaliatory attacks on that night, the burning of the Jaffna Public Library on 1 June, and the attack on Chunnakam on 2 June generated a very tense situation in Jaffna. Night curfew, from 6p.m. to 5a.m., was declared on 3 June.

Around noon on 3 June an additional group of over 250 Sinhala civilian officers were taken to Jaffna in CTB buses. They were kept in Jaffna Central College.

Two strange events occurred on the night of 3 June. Mathew and Gamini visited the Elections Office in Jaffna Secretariat where Elections Commissioner M. A. Piyasekera and Returning Officer Yogendra Duraisamy were giving final instructions to the 150 presiding officers of the polling stations. They took with them the Sinhala civilian officials. Mathew told Duraisamy that they had no confidence in the Tamil presiding officers and wanted them replaced with Sinhala officers.

When Duraisamy refused he was given a written order by Defence Secretary Col. C. A. Dharmapala which directed him to remove the officers already appointed and replace them with Sinhala officers. Dharmapala told Duraisamy that he was giving that direction on a directive from the President.

S. Nadesan

Former Senator S. Nadesan revealed this event a year after the DDC election. Speaking at the Central YMCA in Colombo at the seminar on “Free and Fair Election” organized by the Civil Rights Movement (CRM) Nadesan said, “On the day before the election, the secretary to the ministry of Defence, on the order of the president, had given certain directives to the returning officer. One hundred and fifty presiding officers at the polling booths had been removed and others were substituted. Some of the substitutes were peons in government offices who knew nothing of election procedure. At the end of the poll six ballot boxes were missing.” Senior elections officers present when this incident took place confirmed this.

The second strange event was the arrest of Amirthalingam early morning of 4 June. Around 2.45 a.m. on 4 June, the polling day, about 100 policemen surrounded Amirthalingam’s home at Pannakam and the Inspector who led the party handed to Amirthalingam the arrest warrant Brigadier Weeratunga, the Competent Authority, had issued. The warrant stated that Amirthalingam was being taken into custody on the charge of disrupting the democratic process. Amirthalingam quipped: On the contrary I am trying to help the democratic process. The Police Inspector was apologetic. He said he was only carrying out an order.

Amirthalingam was ordered to sit on a chair in the sitting room while policemen examined the entire house. Amirthalingam told Parliament on 9 June that even his wastepaper basket was emptied and every piece of paper in it was scrutinized. He added the whole operation resembled a major operation to catch a key militant or a major militant base.

Amirthalingam was then taken to the Gurunagar army camp in Jaffna city and kept in a room incommunicado. After day-break Jayewardene spoke to him on the telephone and told him that his arrest had been a mistake and he had ordered his release.

Amirthalingam told me that he was mystified by his arrest. “Might be, the President wanted to help me,” Amirthalingam joked. His arrest had in fact electrified the Tamils. That was one of the reasons for the huge voter turnout that day. Doubts still persist about the origin of the arrest order. The common belief was that Mathew forced Weeratunga to issue the order.

Cyril Mathew

Military sources told me that the decision was taken jointly by Mathew and Gamini.

Security was tightened that day. Police guarded all polling stations and put up checkpoints. Police and Military strengthened the mobile patrol. Military escorted the ballot boxes and the civilian officials to the polling stations and stayed there till the polling concluded and escorted the ballot boxes to the counting centres. Elections law prescribes polling hours as 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. Counting commences after all the ballot boxes are received at the Counting Centre.

Sarath Munasinghe, who was in charge of the Jaffna city polling center, says: “We were ready at the first light. But it was around 10 a.m. buses carrying the ballot boxes started moving to the polling stations. By 6 p.m. we escorted the buses to

the Counting Centre.” On election day, police detained three more leaders: VN Navaratnam, MP for Chavakachcheri; V Dharmalingham, MP for Manipay; and M Sivasithambaram, president of the TULF and MP for Nallur.

Officials said there was a lot of confusion, arguments and shouting. Sinhala civilian officials were sent back to the South as soon as the election was over.

At the Counting Centre there was mayhem. Some ballot boxes had not been returned, which created confusion.

Duraiswamy refused to start the count. Mathew got angry and shouted at him. Piyasekera consulted the Attorney General, who told him that he had no power to invalidate an election and he should direct the Returning Officer to count the available votes in the presence of the representatives of the political parties and independent groups.

Duraiswamy, in his report to the Elections Commissioner, about the election states:

Certain ballot boxes had arrived late. Certain ballot boxes had not arrived at all. A substantial number of counting officers had not confirmed with the requirement that they should submit a written statement about the number of votes cast at each polling station for each political party or independent group that contested the election…

The poll had not been conducted in the proper manner. The TULF did not make a fuss about all that because the UNP’s violence and antics had helped it. The TULF polled a massive 263,369 votes against the UNP’s paltry 23,302, which failed to get Jayewardene even a single seat. The Tamil Congress fared worse, collecting only 21,369 votes. The UNP collected its 23,302 votes by massive impersonation and stuffing of votes. In one ballot box there were 59 ballot papers, all marked for the UNP and stuffed in one bundle. Election Commissioner Piyasekera was unhappy about the government’s attempt to rig the election and sent in his retirement papers to the President as a show of protest. Jayewardene accepted the retirement papers and kept him out of any controversy by appointing him as Sri Lanka’s ambassador in Rome.

The DDC election showed clearly that the Tamils were still with the democratic, non-violent, moderate TULF. They admired the militants and adored their attacks on the police, but were not prepared to place their political future on the hands of the handful of brave and daring youths. Jayewardene failed to learn this simple lesson from the DDC election.

Amirthalingam and the TULF were prepared to cooperate with Jayewardene and work for the DDCs. The TULF picked efficient men with proven administrative skills to head the councils under their control. Former Senator Subramanian Nadarajah was elected the chairman of the Jaffna District Development Council.

Pirapa Leaves Jaffna

The Neerveli Bank Robbery, the arrests of Thangathurai and Kuttimani and incidents of state violence during the DDC elections resulted in the launching of a police and military crackdown on Tamil militants. Pirapaharan found it difficult to stay in his normal hideouts in the Jaffna peninsula. Tired, weak and weary, Pirapaharan sought refuge in Tamil Nadu, leaving behind Mahataya to run the LTTE outfit.

He and his ten trusted men traveled to Vetharaniyam by boat on 6 June 1981.

The journey was not smooth. Pirapaharan asked his trusted colleague, M. K. Sivajilingam of TELO, to arrange a boat for his journey. On the night of 5 June, when the TULF supporters were celebrating their election victory lighting firecrackers, Pirapaharan and ten of his confidantes slipped into a house close to the Valvettithurai police station. The group was armed with a G3 rifle, an AK 47, a sub machine gun, a shotgun and a few revolvers. Accidentally, a rifle went off. But fortunately for them, the bullet got embedded in a mattress. The sound was not heard outside.

Pirapaharan and his men stayed indoors the entire day on 6 June. After nightfall they were stealthily moving to the shore when they saw the headlights of an army jeep. They fell flat on the sand and lay motionless as the jeep streaked past them.

“Inside the boat Pirapaharan fell thoughtful. He looked towards the receding beach and vowed to himself to avenge the insult Jayewardene’s armed gang had heaped on the Tamils,” Kittu, who travelled on that journey, wrote later.

The three days – 31May to 2 June – had intensified Pirapaharan’s resolve to redeem the rights, dignity and honour of the Tamil people.

“The Sinhalese, who with impunity torched Jaffna, the cultural capital of the Sri Lankan Tamils, who burnt down the Jaffna Library, should be taught that Tamils would never be their subject race,” Pirapaharan has told several of his interviewers.

The burning of the Hindu priest in 1958 under S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike rule, the disruption and killing of nine civilians on the final day of the Fourth International Tamil Research Conference in 1974 under Sirimavo Bandaranaike rule, and the burning of Jaffna and the Jaffna Library in 1981 under J. R. Jayewardene’s regime, were the three atrocious events that created and moulded Pirapaharan and fashioned the Tamil armed freedom Struggle.

Once in the safety of Tamil Nadu, Pirapaharan made the necessary preparations to wage the freedom struggle. Since then he has not wavered, since then he has not shirked his commitment.

He opened safe houses in Sirumalai, Pollachi and Mettur, where Tiger recruits were taught how to use walkie-talkies and other wireless communication instruments, and also how to handle arms.