by T. Sabaratnam, March 4, 2005

Chapter 36

Original index to series

Original Chapter 37 [renumbered from Chapter 36, Part 1]

I covered the press conference at the Indian High Commission at Colombo Fort on 14 July 1985, the day after the collapse of the First Round of the Thimpu talks. That was the first press briefing the new High Commissioner, Jyotindra Nath (Mani) Dixit ,who assumed duties on May 26, held in Colombo. By that time, I had befriended him and he was very free with me.

I met Dixit in his room before the briefing. He told me that the Foreign Affairs Ministry had instructed him to hold the press conference and his brief was to tell the Sri Lankan people and the world that the Thimpu talks had not failed and had just begun. “I must do some tight-rope walking. I depend on you,” he said.

I met Dixit in his room before the briefing. He told me that the Foreign Affairs Ministry had instructed him to hold the press conference and his brief was to tell the Sri Lankan people and the world that the Thimpu talks had not failed and had just begun. “I must do some tight-rope walking. I depend on you,” he said.

The press conference was really a tight-rope walking exercise even for Dixit, an experienced media relations diplomat. He had earlier been the Foreign Affairs Ministry’s official spokesman.

Dixit started off by saying that the Thimpu talks were a success and not a failure as some reports from Thimpu had stated. The talks were a success because they had brought the Sri Lankan Government and the Tamil militants, who had been fighting for some years, to the negotiating table, he said. They were a success because the Sri Lankan government had placed on the table a set of proposals for the resolution of the conflict and the Tamils, who asked for improvement, had enumerated the basic principles that need to be embodied in a solution. “So both sides have stated their negotiating positions and several rounds of bargaining are needed to narrow down to a solution acceptable to both sides,” Dixit said.

Dixit said the fact that both parties had decided to meet again on 12 August was an indicator that the negotiation process had begun with earnestness. He added that India would continue to play its role to help both sides move towards a solution.

But most of the Sinhala journalists were more concerned about blaming India for creating the need to talk with the Tamils than in finding out what happened in Thimpu. They repeatedly asked him about India training and arming ‘Tamil terrorists’ and blamed India for doing so. One reporter asked pointedly, “Do you admit that if India did not train and arm them the need for talks would not have arisen.”

Dixit dodged those questions. He did not admit or deny India training and arming Tamil militants. He kept on saying that they should look at the future and not harp on the past. “The dialogue has commenced and it should continue’ was his refrain.

Reporters representing the Tamil media questioned Dixit about the continuance of the ceasefire. They were reflecting the fear among the Tamil people that ceasefire would break because the armed forces were intensifying their cordon and search operations. Incidents of attacks on Tamil civilians were also reported. Dixit make a special effort to alley the fear of the collapse of ceasefire. He said, “Ceasefire is holding. It will hold.”

But that evening the ENLF issued a strong statement in Chennai. It warned that its fighters would retaliate if the armed forces continued their hostile activities. Six days later, on 20 July, LTTE fighters fought a pitched battle with an army unit and killed one soldier. On 25 July, the second anniversary of the 1985 pogrom, Black July, the militant groups called for a general shutdown in the north and east. People obeyed the call. They put up black flags to mourn the death of the 52 Tamil detainees at Welikada prison. Jaffna was rocked by a series of bombs which the militants exploded as a mark of respect for the slain Tamil leaders.

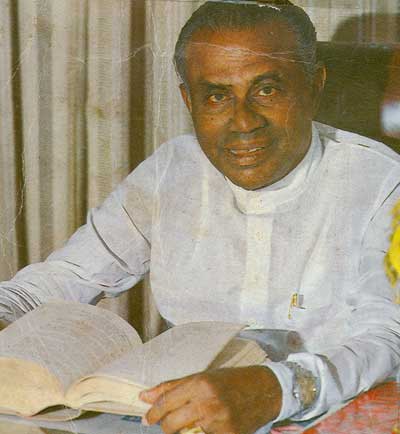

Sirimavo Bandaranaike

By that time, Dixit had started a series of meetings with Sinhala and Tamil leaders to gauge the ground situation. He called on SLFP leader Sirimavo Bandaranaike on 16 July, two days after the press meet and she told him she anticipated the failure of the Thimpu talks because Jayewardene was not sincere about coming to terms with the Tamils. She also told him that Jayewardene was vindictive and knew only violence. “He has opted for a military solution and he will not veer from that path,” she told him.

Dixit met Hector Jayewardene on 23 July and asked him whether it would be possible to make improvements to the government proposals. Dixit refers to that discussion in Assignment Colombo (Page 32). But Hector Jayewardene told Dixit he would negotiate within the boundaries set by the existing constitution. He promised to make improvements in the government proposals within that limit.

Exasperated by this approach, Dixit states in his book Assignment Colombo (Page 32), that he pointed out that the focus of the Tamil struggle was against the constitution. Tamils want the constitution changed to enable the structure of the state to be altered from unitary to federal. Dixit states that he also pointed out to Hector Jayewardene that, if that change is not effected, the Tamils might proceed with their struggle for a separate state.

Dixit records Hector Jayewardene’s response thus: Jayewardene’s response was wooden. He said: I can only negotiate within the framework of the constitution of the country. What you are pointing out is a political matter. This cannot be discussed with the Tamils without Sri Lankan Government, the Buddhist clergy and the Sri Lankan public agreeing to such a proposition.”

Basic Position

Dixit met Dr. Neelan Tiruchelvam the next day, 24 July. Neelan Tiruchelvam told him that Tamils felt that Bhandari had failed to understand the complexities of the Tamil problem. He also told Dixit that Bhandari’s anxiety to work out a solution fast had given Jayewardene room to think that he could carry on some cosmetic negotiations with the Tamils without yielding on any matter of substance.

Neelan Tiruchelvam impressed upon Dixit that the preservation of the Tamil homeland, which he said the Sinhalese were trying to split into two portions through state-aided colonization schemes, and the recognition of the right of the Tamils to rule themselves in their homeland, are fundamental to any solution. Tamils would not accept anything less than that, he told Dixit.

Dixit told Neelan Tiruchelvam that the TULF should make this position clear to Bhandari and Rajiv Gandhi. “I have been called to Delhi to prepare a document to be sent to President Jayewardene suggesting the basis for a solution. I will be going tomorrow. If the TULF would send a document stating what you just told me, it would help the preparation of that document,” Dixit told Neelan.

Neelan communicated that information to Amirthalingam who was in Chennai. Amirthalingam and Sivasithamparam then a sent a letter stating their negotiating position to Rajiv Gandhi on 26 July, The following are the main paragraphs in that letter:

The fundamental basis for any solution to the Tamil problem will be the recognition of the right of the Tamil people to rule themselves in their homeland. Serious inroads have been made into these homelands by a policy of planned colonization with the Sinhalese, carried out by successive Sinhala governments since independence, in the teeth of opposition by the Tamil people and in violation of solemn undertakings given by Prime Ministers on the same pattern as Israeli settlement in occupied Palestine.

The government is trying to seek advantage of this and divide the traditional homeland into two, thereby paving the way for the destruction of the Tamils in the Eastern Province. In spite of the claim by President Jayewardene, we are confident that you will not regard this as a just method of solving the problem. The Tamil people will never accept a bifurcation of their territory.”

Dixit went to Delhi on the evening of 27 July. On the same morning C. Anandarajan, Principal, St. John’s College was murdered. He was shot because he arranged a friendly cricket match between the college team and the Sri Lanka Army at the college grounds. He was warned by an LTTE fighter not to do so. He retorted: You are talking to the Sri Lankan government at Thimpu. What is wrong in our boys playing a cricket match against the army?

The army had planned a series of friendly cricket and soccer matches against the leading schools in Jaffna as part of its “hearts and minds” campaign to win over the people of Jaffna. Militant groups decided to stop it as they felt that would affect their program of mobilizing the people against the Sri Lankan State. An LTTE fighter (now he is living in a western country) killed Anandarajan. The LTTE put up posters claiming responsibility. The LTTE said he was shot when he declined to listen to several warnings. The shooting had the desired effect. The friendly match program was scrapped.

The army had planned a series of friendly cricket and soccer matches against the leading schools in Jaffna as part of its “hearts and minds” campaign to win over the people of Jaffna. Militant groups decided to stop it as they felt that would affect their program of mobilizing the people against the Sri Lankan State. An LTTE fighter (now he is living in a western country) killed Anandarajan. The LTTE put up posters claiming responsibility. The LTTE said he was shot when he declined to listen to several warnings. The shooting had the desired effect. The friendly match program was scrapped.

The government played up the incident as a serious violation of the ceasefire. The police offered 500,000 rupees as reward for information about the shooting. They did not get any information.

During his next four-day stay in Delhi, Dixit met with Rajiv Gandhi, G. Parthasarathy who had been sidelined, Saxena and the legal officers of the External Affairs ministry. During their discussions, they prepared a document which outlined the improvements Sri Lanka should make in its proposals to make it responsive to the fundamental demands of the Tamil side without jeopardizing the unity and territorial integrity of Sri Lanka. The document, which in diplomatic parlance was referred to as a Non-Paper because it contained no-binding suggestions, wanted improvements in structure and powers to Sri Lanka’s District Councils Scheme. On the structure of the state, the document suggested the establishment of Provincial Councils as the basic units of government and permanent linkage between the northern and eastern Provincial Councils as a response to the Tamil demand for a homeland. On the powers of the Provincial Councils, it suggested devolution of financial powers, powers over land and the law and order mechanism. It also suggested that Tamil be made an official language.

Prof. G. Parthasarathy with Mr. Rajiv Gandhi on board a Aircraft when they were travelling to Moscow in 1989

Neelan Tiruchelvam, who was given a copy of the Non-Paper by Dixit just before the second round of talks began, told me that these were the contributions of Parthasarathy. “Bhandari and Saxena never understood these matters,” Neelan said.

Rajiv Gandhi instructed Dixit to hand over the Non-Paper to President Jayewardene and prepare the ground for another visit by Bhandari. Dixit returned on 2 August and called on Jayewardene at his Ward Place residence at 7 p.m. the same day. Lalith Athulathmudali was also present.

Dixit gives the content of the discussion in Assignment Colombo (Page 33). He says that he conveyed the Government of India’s disappointment about the failure of the talks at Thimpu and handed over the Non-Paper. Dixit had told Neelan Tiruchelvam that President Jayewardene read the Non-Paper, smiled, and handed it to Lalith Athulathmudali.

Dixit then conveyed to Jayewardene the Indian feeling that Sri Lanka’s proposals submitted at the first round of Thimpu talks was too little to induce the Tamil groups to respond in a positive way. Lalith Athulathmudali intervened with the abrasive retort: Sri Lanka cannot accept unilateral demands by the Tamils just because India backs them.” Dixit says that Lalith Athulathmudali gave him a brief lecture on India’s support to Tamil militants.

Jayewardene then told Dixit that Hector Jayewardene would lead the Sri Lankan delegation for the second round also and said he would hand over the Non-Paper to him. He also told Dixit that Bhandari would be welcome and he would give him a patient hearing.

Bhandari arrived in Colombo on 8 August and called on President Jayewardene, Prime Minister R. Premadasa, Foreign Minister A. C. S. Hameed, Athulathmudali, Sirimavo Bandaranaike and Hector Jayewardene.

The meeting with Jayewardene was unproductive. Bhandari told him that his government should make an offer on the lines indicated in the Non-Paper and try to clinch a political solution. He told Jayawardene that India considered the second round of Thimpu talks as crucial. If it failed, he warned, Sri Lanka would face tragic consequences.

The meeting with Jayewardene was unproductive. Bhandari told him that his government should make an offer on the lines indicated in the Non-Paper and try to clinch a political solution. He told Jayawardene that India considered the second round of Thimpu talks as crucial. If it failed, he warned, Sri Lanka would face tragic consequences.

Jayewardene was not that responsive. He did not get involved in serious talk. He passed the buck to his brother Hector Jayewardene and Lalith Athulathmudali. He told Bhandari that, since his brother would again head the Sri Lankan delegation, he should conduct his detailed talk with him. He also said Lalith Athulathmudali would also talk to him in detail.

The talk with Premadasa was of a general nature. As usual Premadasa prefaced his talk about his respect for Mahatma Gandhi and his affection to India. He told Bhandari that India should help Sri Lanka to contain terrorism. “As long as Tamil terrorism persists, the prospects of a political solution is remote,” he said. He added that the Sinhala pride had been wounded and they are not in a mood for any accommodation. He also told Bhandari the the Sinhala people appreciated India’s desire for peace and stability in Sri Lanka, but were not happy about its mediatory efforts. “They feel that India is favouring the Tamils,” he said.

Sirimavo Bandaranaike told Bhandari she anticipated the Thimpu talks to fail. She said Jayewardene was not sincere. She predicted the next round would also be futile.

Bhandari pleaded with Hector Jayewardene to refrain from discussing past events at the conference, but to concentrate on the future. He told Jayawardene that the Non-Paper indicated the areas in which India would like Sri Lanka to make improvements. Hector Jayewardene told Bhandari that he would negotiate within the ambit of the 1978 constitution and undertook to come with structured proposals.

Lalith Athulathmudali rejected outright all the improvements India had suggested in its Non-Paper. He told Bhandari that Sri Lanka would not agree to the linkage of the Northern and Eastern Provinces. He said in the Eastern Province Muslims and Sinhalese together formed the majority. And he argued that in the 1977 parliamentary election the TULF had not gotten the mandate for a separate state in the Eastern Province. He added that in the 1982 Presidential election and the Referendum the Eastern Province had voted with the government.

Athulathmudali also rejected the demand for improved powers for the Provincial Councils. He said the Sinhala people would not agree to vest the Provincial Councils with financial power or to give them powers over land and law and order. He said the government did not have the power to meddle with the Sinhala Only Act, or the unitary character of the constitution which had been entrenched in the 1972 and 1978 constitutions. “In these matters the government and the opposition are one,” he asserted.

Athulathmudali’s role

Jayewardene was a master political strategist. He would negotiate with the Tamils to keep them satisfied and, at the same time, take steps to please the extremist sections of the Sinhalese. He would talk to the Tamils to please India, the international community and the donor nations and, at the same time, create persons in his cabinet to voice extreme Sinhala views to keep the Sinhala hardliners with him. Above everything, he would paint himself a reasonable man struggling against a group of Sinhala hawks in the cabinet.

Anita Prathap figured this out in her very first interview with him in 1984 when he told her that he would have solved the Tamil problem but for his Sinhala extremist ministers. She called him, in her article to the popular Tamil magazine Kalki, an actor. Pirapaharan also understood Jayawardene, as I pointed out in an earlier chapter. Pirapaharan said Jayewardene was all powerful and his extremist ministers were his creations. I support these assessments. Jayawardene played political chess, made tricky moves, but lost in the end. He lived to see Pirapaharan create a de facto state within the sovereign state he ruled.

In 1977 Jayewardene created Cyril Mathew as a Sinhala chauvinist champion. Jayawardene wanted a person to take the hard position against the Tamils, especially against Amirthalingam and the TULF. In the first volume of this series, I recorded the answer he gave Amirthalingam when he protested against Mathew’s attacks on him and the Tamils. Amirthalingam told me that Jayewardene had told him that he was using Mathew to carry with him the Sinhala extremists. (Also refer my book Murder of a Moderate, Page 261 published in 1996)

Amirthalingam told me he asked Jayewardene,” How can we support the government when we are attacked by a government minister?” Jayewardene’s reply according to him was, “Don’t worry about him. There is some dissatisfaction among Sinhala extremists about our close relationship with your party. Mathew’s role was to keep them satisfied.”

Jayewardene chose Mathew to play that role because his caste and social standing posed no threat to himself. He used Mathew as a tool and threw him away when he felt dismissing him would benefit himself politically. Mathew was dismissed in early 1985. His dismissal did not create even a whimper, which proved that he was Jayewardene‘s creation and depended on him, rather than having his own political base.

After the dismissal of Mathew, Jayewardene needed another to play that role. Lalith Athulathmudali was his choice. During my close association with Lalith Athulathmudali, I realized the extent to which he depended on Jayewardene and tried to act as his mouthpiece. I can relate several instances to substantiate this statement. After a briefing during the All Party Conference in 1984 Athulathmudali called me aside and told me the conference had considered President Jayewardene’s suggestion to make English as one of the national languages. He asked me to give prominence to that story. Under the 1978 constitution, English was only a link language.

When I returned to the Daily News editorial after the press conference my editor, Manik de Silva, told me that Athulathmudali had telephoned him and said that he had given me a top story. I told Manik the story and wrote it. It was the lead next day with my byline. I met Athulathmudali that evening. He told me that President Jayewardene asked him whether he had given the story. Athulathmudali told me that his reply was: “I gave it because I thought that you would like it.” He said the President was pleased with the story.

Soumiyamoorthy Thondaman

Lalith Athulathmudali was ambitious. He wanted to succeed President Jayewardene. He knew that President Jayewardene had a soft corner for his main rival, Gamini Dissanayake. The only way he could overtake Gamini Dissanayake was to play the role Jayewardene wanted him to play – the role of the Sinhala hardliner.

S. Thondaman told me several times about this ‘old man’s game.’ He expressed a similar view to Dayan Jayatilleke and S. Balakrishnan soon after Mathew’s dismissal. A report of that interview was reprinted in the Lanka Guardian of 15 November 1985.

Question: After the dismissal of Cyril Mathew from the cabinet, there was an expectation that there will be a speedy resolution of the ethnic conflict. But, that does not seem to have taken place. Would you say that even despite Mr. Mathew’s dismissal there is still a hard line Sinhala presence in the government which is blocking the attempts of some to resolve the ethnic problem?’’

Thondaman: First of all, I am of the opinion that the decision taken to dismiss Mr. Mathew from the cabinet was not a correct decision at the time. If he was dismissed when everybody suspected JSS (Jathika Sevaka Sangamaya, UNP’s trade union which Mathew headed) involvement it was understandable. But now, the entire thing was over, the damage had been done and what is the use of removing him at this later stage? There is a feeling in the UNP that, as a whole, the people may think that the UNP has lost its Sinhala-Buddhist aspect after the dismissal of Mathew. So they go all the way to make the Sinhala people to believe that the UNP is still very strong in Sinhala influence. I think that in this way more damage is being done. On the one hand, the President may think that he has dismissed Mr. Mathew and therefore Tamils must be satisfied; many people think that this is cause for satisfaction for the Tamils. But I don’t consider that the Tamils are concerned that whether Mr. Mathew is, in or out. What they expect is the removal of all the injustices.

Athulathmudali played the role of satisfying the ‘Sinhala-Buddhist aspect’ when he rejected all the improvements India had suggested in the Non-Paper. Jayewardene played the just-man role against Athulathmudali’s role of hardliner. By doing so, Bhandari was smartly outmaneuvered by Jayewardene.

Bhandari met the leaders of the Tamil groups and Chief Minister M. G. Ramachandran at Chennai on 10 August on his return journey to Delhi. He took Dixit with him for those meetings, which were held separately. Bhandari met MGR at his estate where Bhandari said President Jayewardene had promised to make improvements on the proposals submitted during the first round of talks and urged him to use his influence with the Tamil groups to be more accommodative.

Raj Bhawan, Chennai 2021

The meeting with the leaders of the Tamil groups took place at Raj Bhawan, the official residence of the Governor where Bhandari stayed. Pirapaharan attended that meeting along with the other leaders of the ENLF. Balasingham went with Pirapaharan. Bhandari gave the details of the discussions he had with President Jayewardene and other leaders in Colombo. He told them that Hector Jayewardene would come to Thimpu with an improved package of proposals and requested the Tamil groups not to reject them, but to act realistically. He advocated that they accept what was offered and build on the package over a period of time.

As agreed at the ENLF planning session held earlier that day, Pirapaharan spoke first. He, as usual, spoke in Tamil and Balasingham interpreted. Pirapaharan rejected the long-term approach, saying that that had proved a failure. He told Bhandari that democratically elected Tamil leaders led by Gandhian S. J. V. Chelvanayakam had tried that approach from 1956 to 1977 and had failed. Chelvanayakam had entered into written agreements with Prime Ministers S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike and Dudley Senanayake, but the agreements had not been honoured. Making use of talks to lull Tamil opposition and let them done had been the strategy the Sinhala leadership had employed before. The ENLF were not prepared to travel along that failed track any more.

Pirapaharan also pointed out their belief that Jayewardene had deceived the TULF in the same manner from 1977 to the present (1985). He told Bhandari that they did not trust Jayewardene. He also expressed his displeasure about the way India forced the ENLF to go to Thimpu. He implicitly warned Bhandari that Jayewardene was trying to outmaneuver India and weaken the Tamil struggle. He told Bhandari the Tamil groups would go to Thimpu for the second round of talks out of respect for him and Rajiv Gandhi, but they were certain Sri Lanka would not come with a worthwhile proposal. He added that they would not yield on the four basic principles they had propounded in the first round of talks.

Bhandari was annoyed. He told the ENLF leaders not to talk in abstract terms. “Be realistic,” he kept advising them. Pirapaharan was adamant. He refused to budge.

Bhandari had separate meetings with TULF and PLOTE leaders. They also told him about their distrust of Jayewardene. They told Bhandari that the rejection of the basic Tamil positions by Athulathmudali presaged the failure of the second round of talks. Amirthalingam told Bhandari: “Our response depends on the government proposals. If they come up with some cosmetic adjustments to the District Council proposals, we have to reject it.”

Dixit records in Assignment Colombo (Page 37) the frustration of Bhandari. He wanted to achieve a quick breakthrough because his period of office lasted only till March 1986. He had put a huge effort to work towards a solution to the Sri Lankan issue. Dixit says that, from the tenor of Bhandari’s conversation with the Tamil leaders, he got the impression that Bandari was “both irritated and disappointed” with the Sri Lankan Tamils. He felt that the Sri Lankan government was employing dilatory tactics and the Tamil leaders were obstinate.

Neelan Tiruchelvam

Later that evening, when they were alone, Bhandari asked Dixit whether, he had given a copy of the Non-Paper to the TULF leaders. When Dixit told him that he had not as he had no instruction to do so, Bhandai told him: “Mani, as soon as you reach Colombo hand over the documents to Chelvanayakam.” When Dixit told him that Chelvanayakam was dead and he must have meant Tiruchelvam, Bhandari blurted: Mani, give this paper to Chelvanayakam, Tiruchelvam whoever it is. All these South Indian names are very confusing.” Dixit handed over the Non-Paper to Neelan Tiruchelvam on his return to Colombo.

While Bhandari was pressing the Tamil groups at Chennai to be reasonable, things were hotting-up in Vavuniya and Trincomalee. Militants exploded a police jeep using a land mine in Vavuniya and killed a sub-inspector and four policemen. Security forces retaliated in Vavuniya and Trincomalee. In Vavuniya, they shot civilians and burnt shops and houses. Ten civilians died in that incident and 21 were injured. In Trincomalee, eight Tamil refugees playing cards outside a refugee camp were shot and killed by gunmen.

But generally the ceasefire held.

Legalistic Approach

Sri Lanka sent the same delegation headed by Hector Jayewardene to Thimpu. The Tamil side made only one change. Nadesan Satiyendra, the lawyer who had argued the famous Thangathurai case in the Colombo High Court, replaced Mohan of the TELO.

Sri Lanka sent the same delegation headed by Hector Jayewardene to Thimpu. The Tamil side made only one change. Nadesan Satiyendra, the lawyer who had argued the famous Thangathurai case in the Colombo High Court, replaced Mohan of the TELO.

The second round of Thimpu talks resumed on 12 August. Hector Jayewardene read out a prepared statement. “Before we place before you further proposals for the devolution of power in the light of the views expressed at the several meetings held in Thimpu in July, we think it is necessary to state the government’s understanding of the four principles set down in the statement dated 13 July 1985, made on behalf of the six groups representing the interests of certain Tamil groups in Sri Lanka,” he began.

This introduction itself agitated the Tamil side. Hector Jayewardene then repeated the position he took at the beginning of the first round that the Tamil side did not represent the Tamil people of Sri Lanka. During the first round, he maintained that his delegation represented the Tamil people also. When the Tamil side threatened to walk out, he conceded that the Tamil side was representative enough to talk abouit a political solution. This compromise position he took was criticized in Sri Lanka by Sinhala extremists.

Hector Jayewardene, in his lengthy constitutional argument, rejected the four basic principles the Tamil side proposed as the basis for a political solution acceptable to the Tamil people.

Firstly, he rejected the Tamil position that the Tamils of Sri Lanka constitute a distinct nationality. He argued that the acceptance of the concept that Sri Lankan Tamils form a distinct nationality would amount to the acceptance of the position that they are entitled to create a separate state. At best, he contended, what the government could accept was that Sri Lankan Tamils constitute a distinct ethnic group. He said the government delegation was prepared to consider proposals concerning the rights of the Tamils as an ethnic group. He added, “We will guarantee the rights in the Constitution, create a minorities rights commission, and if necessary, a chamber in which they will receive adequate representation.”

Secondly, he rejected the concept of an identifiable Tamil homeland. He argued that the concept of an identified Tamil homeland meant the preservation of a identified territory of Sri Lanka for the Tamils. That violated the principle that the entire country is the territory of all of its citizens. It also violated the fundamental freedom of the citizens to settle anywhere they desire. It also prevented starting of settlement schemes in the area demarcated as the Tamil homeland. He said the government was prepared to give preferential treatment to the Tamils in the settlement schemes in the north and east.

Thirdly, he vehemently rejected the demand for the recognition of the right of self-determination. He argued that concept applied only to people living under colonial rule. He said minority communities living in independent sovereign states do not enjoy the right of self-determination.

Finally, he challenged the status of those on the Tamil side to speak about the question of citizenship. He said the government had announced at the All Party Conference its decision to grant citizenship to the stateless persons and that problem would be settled with the authentic representatives of the people of recent Indian origin.

Jayawardene ended his statement with a bombshell announcement. He said any agreement reached at Thimpu would be implemented only if:

- All militant groups completely renounce all forms of militant action.

- All militant groups in Sri Lanka surrender their arms and equipment.

- Close down all training camps whether in Sri Lanka or abroad.

- Refugees wherever they may be must be permitted to return unmolested to areas which were inhabited by them prior to their disturbance and destabilization.

- All temples, kovils, churches, mosques and other places of worship and shrines of whatever religion damaged or destroyed should be restored and people of all communities and religions, wherever they may be shall be allowed to manifest their religion in accordance with the guarantees in the Constitution.

- An amnesty for all violations of the criminal law pursuant to agitations of the militant groups would only be granted after the government is satisfied that these pre-conditions have been observed

“This is the only basis on which any settlement reached here can be implemented and peace restored to our country,” Hector Jayewardene concluded.

LTTE chief delegate Thilagar conveyed the substance of Hector Jayewardene’s rejection of the four basic principles to Balasingham, who was at the secret location in Kodampakkam, through the hot line. Balasingham had a hurried consultation with the ENLF leaders and Pirapaharan, who was at the LTTE camp at Salem.

The decision to quit the talks was made. The ENLF leaders decided to await an appropriate moment.

Annexure

The text of Hector Jayewardene’s opening statement:

“Before we place before you further proposals for the devolution of power in the light to the views expressed at the several meetings held in Thimpu in July, we think it is necessary to state the government’s understanding of the four principles set down in the statement dated 13th July, 1985, made on behalf of the six groups representing interests of certain Tamil groups in Sri Lanka. We also take the opportunity to explain the relevance of the government’s proposals to the four principles.

“Firstly, we wish to observe that there is a wide range of meanings that can attach to the concepts and ideas embodied in the four principles and our response to them would accordingly depend on the meaning and significance that is sought to be applied to them.

“Secondly, we must state emphatically that if the first three principles are to be taken at their face value and given their accepted legal meaning they are wholly unacceptable to the government. They must be rejected for the reason that they constitute a negation of the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Sri Lanka. They are detrimental to a United Sri Lanka and are inimical to the interests of the several communities, ethnic and religious in our country.

“But in so far as these ideas and concepts can be given a meaning and connotation which does not entail the creation of a separate state, or a structure of government that is indistinguishable from a separate state, we do believe that there is room for a fruitful exchange of views, which can result in a settlement of the problems that besets us. The proposals that were put before you in July were designed to remedy existing grievances and at the same time, we shall elaborate on them to show how they can serve as the foundation for a lasting settlement, but before we do that let me state briefly our position on the four basic principles.”

Tamils as a distinct nationality

“The ambiguity of meaning contained in the first basic principles arises from the use of the words ‘a distinct nationality’ in international law. The nationality of an individual signifies the quality of his being the subject of a certain state, of owing allegiance to that state, and of being entitled to its protection. If the words ‘distinct nationality’ indicate a separateness as a distinctness from other communities or racial groups in the land by virtue of difference in the obligation of their allegiance, this principle would involve the creation of a new state [or its equivalent] and we must unequivocally reject it. There can be no question of a distinct nationality in this sense.

“Outside the field of international law, the word ‘nationality’ also signifies a group or community having an ethnic identity of its own. It is used then as a historic-biological term denoting a racial group which is a constituent element of a wider community of people who constitute the nation in that state. In that sense, there is room for a proper distinction to be drawn and for recognition of a separateness of identity. In that sense, also we recognize the existence of the Tamils as a distinct community and their right to a status of equality and dignity with the rest of the communities which constitute the Sri Lankan nation.

“We are certainly prepared to consider any proposals that would help the preservation and protection of those rights and interests, which are necessary for the continuing existence of the Tamils as an ethnic group. Our present proposals have taken note of these values and we shall consider any specific proposals that you wish to make in this regard. Such proposals must of course recognize the existing rights of all communities and religions in Sri Lanka.

“We recognize the right of all communities in Sri Lanka to preserve, protect and promote their cultural heritage and linguist traditions, and to practice their religion. Such recognition ought not to prejudice the sovereignty of the state.

“The Constitution of Sri Lanka guarantees to all communities throughout Sri Lanka, however small their numbers may be in any part of the island, their rights in respect of culture, language and religion, for the government recognizes the whole of Sri Lanka as the homeland of member of every community. We will guarantee the rights in the Constitution, create a minorities right commission, and if necessary, a chamber in which they will receive adequate representation.

“The Constitution and other laws dealing with the Official Language, Sinhala, and the National Language, Tamil, with English as the link language are accepted and will be implemented as well as similar laws dealing with the National Flag and Anthem.

“The state services including the security services will adequately reflect the National Ethnic Proportion. In Higher Education too, the system of admission to the universities will in its operation substantially reflect the ethnic proportion of the Island.”

An identified Tamil homeland

“The second basic principle speaks of the recognition of an identified Tamil homeland and the guarantee of its territorial integrity. The precise implications of the concepts of a physically demarcated area of Sri Lanka being the homeland of the Tamils are not clear. Taken in conjunction with the demand that its territorial integrity be guaranteed, there is implicit in this the idea of a truncation of the republic’s own territorial integrity, as defined by Article 5 of the Constitution. I need hardly say that any such idea cannot be entertained, let alone considered.

“In so far as this principle contains the implication that there is to be a total or partial embargo placed against the settlement of people of other communities in the areas perceived by the Tamils as their homeland, we reject it as being a violation of the fundamental rights and freedoms of all citizen of Sri Lanka.

“It is the right and freedom of every citizen of Sri Lanka, irrespective of the racial or religious group to which he belongs, to settle in any parts of Sri Lanka which has been the homeland of all communities from the time immemorial. All citizens irrespective of community are entitled to the freedom of movement and of choosing their residence in any part of Sri Lanka and of engaging in any lawful occupation anywhere in the country.

“On the other hand, we do recognize the fact that in certain parts of the country there are strong concentrations, which had given rise to special problems. In so far as there is a need to recognize their special rights and claims to preferential treatment which are not inconsistent with the fundamental principle of equality and equal protection and in so far as it is necessary to accord any special rights to the Tamil community living in these areas, for the preservation of their ethnic identity, we are prepared to consider reasonable proposals for achievement of these objectives. We shall place before you specific proposals, for land settlement and land use, which in our opinion do satisfy this need.

“In considering the rights of the Tamil community and need to recognize certain special rights of the Tamil community in certain areas, it is necessary to bear in mind the distribution of the population in the country. Sri Lanka’s population of 14,850,000 includes several ethnic groups:

Sinhalese: 74%

Sri Lankan Tamil: 12.6%

Muslims: 7.4%

Indian Tamils: 5.6%

Burghers: 0.26%

“While the majority of the Sinhalese are Buddhists, the majority of the two Tamil communities are Hindu. The Muslims are followers of Islam. The Christians belong to all communities.

“The distribution of the population district-wise is as follows:

| District |

% total pop |

Sinhalese |

SL Tamils | Muslims | Indian Tamils |

| Colombo |

11.43 |

77.88 |

9.77 |

8.27 |

1.27 |

| Kalutara |

5.57 |

87.29 |

1.04 |

7.46 |

4.05 |

| Gampaha |

9.35 |

92.18 |

3.6 |

2.77 |

0.41 |

| Kandy |

7.5 |

75.22 |

4.89 |

10.67 |

9.29 |

| Matale |

2.41 |

79.87 |

5.86 |

7.22 |

6.73 |

| Nuwara Eliya |

4.04 |

42.17 |

12.48 |

2.47 |

42.40 |

| Budulla |

4.32 |

68.48 |

5.7 |

4.17 |

21.12 |

| Moneragala |

1.88 |

92.88 |

1.8 |

1.9 |

3.28 |

| Galle |

5.48 |

94.40 |

0.74 |

3.18 |

1.36 |

| Matara |

4.33 |

94.59 |

0.61 |

2.55 |

2.16 |

| Hambantota |

2.86 |

97.37 |

0.37 |

1.12 |

0.07 |

| Kurunegala |

8.17 |

93.06 |

1.16 |

5.06 |

0.53 |

| Puttalam |

3.32 |

82.59 |

6.73 |

9.72 |

0.60 |

| Anuradhapura |

3.84 |

92.11 |

1.04 |

6.52 |

0.13 |

| Polonnaruwa |

1.76 |

90.89 |

2.24 |

6.05 |

0.08 |

| Ratnapura |

5.36 |

84.71 |

2.26 |

1.7 |

11.01 |

| Kegalla |

4.6 |

86.26 |

2.07 |

5.1 |

6.43 |

| Trincomalee |

1.85 |

35.8 |

31.99 |

28.78 |

2.48 |

| Batticaloa |

2.23 |

3.22 |

70.82 |

23.97 |

1.17 |

| Amparai |

2.62 |

37.65 |

20.14 |

41.53 |

0.36 |

| Jaffna |

4.98 |

0.51 |

97.07 |

1.69 |

0.67 |

| Kilinochchi |

0.62 |

0.91 |

81.22 |

1.38 |

16.39 |

| Mannar |

0 .72 |

8.14 |

50.59 |

26.62 |

13.16 |

| Vavuniya |

0.64 |

16.55 |

56.87 |

6.92 |

19.39 |

| Mullaitivu |

0 .52 |

5.09 |

75.95 |

4.87 |

13.89 |

“It is also relevant to comment on the ambiguity in the use of the expression ‘Tamil homeland’. The ‘homeland’ is claimed not on behalf of all the Tamil-speaking people of Sri Lanka, which would include the Muslims, as well as the Tamils of recent Indian origin. It is also significant that the earlier expression ‘The Traditional Homelands of the Tamils’ which had been used to stake a claim for the entirety northern and eastern provinces, as certain other areas, such as Puttalam, has now been dropped.

“The claim of the ‘Traditional homelands’ was originally framed on the alleged historical basis that these ‘homelands’ existed ‘for centuries from the dawn of history’. It was subsequently claimed to have existed from about the 13th century with the establishment of the ‘Kingdom of Jaffna’. Evidently the present statement avoided the use of the expression ‘Traditional Tami Homelands’ from a realization of the dubious nature of the historical evidence.

“In the context of the expression ‘Tamils of Sri Lanka’ the expression ‘Tamil Homelands’ is thus sought to be given an expanded significance so as potentially to include the central highlands, parts of the Uva and Sabaragamuwa provinces as well. Even if the claim be limited to the northern and eastern provinces it would in effect cover approximately 30 percent of the land area and 60 percent of the sea coast of Sri Lanka and that too on behalf of only 12.6 percent of the population. If the claim were to include the additional areas referred to above, it would encompass very nearly half the land area of Sri Lanka and that too on behalf of 18.2 percent of the population. These facts alone demonstrate the utter unreasonableness and injustice of this demand and would be reason enough for its rejection.

“The Tamil leadership has hitherto rejected any proposals for the equitable distribution of places in state employment or state education, especially in the matter of university admissions based on national ethnic proportions on the grounds that there should be strict equality of opportunity. Inconsistently with this principle, however, the ‘Tamil Homelands’ demand involves a special reservation for Tamils in respect of land settlement schemes in the Northern and Eastern provinces of Sri Lanka. These areas also happen to be the areas in which major settlement schemes are foreshadowed in the future, which would mean a monopoly of the use of these lands for the Tamils. The contradiction involve in the demands in these two fields must therefore be emphasized.

“It is, however, possible to discuss land settlement and land use under this head with due regard to any reasonable demand of the Tamils without in any way accepting or conceding this claim of ‘Tamil Homeland’.”

The right of self-determination of the Tamil nation

“The third principle of the right of self-determination, in so far as it implies the right of a secession from and out of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, and the right to create a separate state is totally unacceptable and is in this form rejected. International law and practice does not regard the principal of self-determination as one which authorize any group of people to take any action that would result in the dismemberment or impairment of the territorial integrity or political unity of a sovereign and independent state.

“International law recognizes that the right of self-determination applies only to colonial peoples striving to win independence from foreign domination and does not apply to sovereign independent states, or to a section of a nation. It cannot be used as a means of destroying national integrity.

“All governments in Sri Lanka since independence have recognized the right of all citizens, irrespective of race and religion to participate in the democratic process of electing the government of their choice and of participating through their elected representatives, in decisions regarding, the framework of government and in the management of their own affairs. This is the only sense in which the government and in the management of their own affairs. This is the only sense in which the government of Sri Lanka recognizes the principle of self-determination in the business of government. [This right of self-determination in the business of government.] This right of self-determination is exercisable within the existing constitutional framework by all the citizens of Sri Lanka in respect of their political, economic, social and cultural affairs. One group of people living in an independent, sovereign state does not have the right to determine their future political status independently of the rest of the people living in that country and do not have the right to secede from the existing state to form and establish an independent state. In our view, the right of self-determination is available only to the political entities under colonial rule.

“The UN resolution 1514 (xv) clearly states that any attempt aimed at the partial or total disruption of the national unity and territorial integrity of a country is incompatible with the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations. The rights of all minorities living in Sri Lanka are already protected by the constitution of course. There can be groups who are dissatisfied with the degree of participation that they now enjoy. The prepared scheme of devolution of power is designed to meet these demands to a very substantial degree. This refusal to identify or specify particular areas of dissatisfaction or to examine facts on which complaints are based does create in our minds the impression that the grievances are either exaggerated or not bona fide. We would therefore earnestly request you to specify the particular problems and put forward your proposals for remedial action so that we may consider them on their merits. We do not recognize the need to create special status for the Tamil minorities which is not recognized in the case of other communities living in Sri Lanka.

“It is relevant to mention in this connection that at the 1977 general election only the TULF campaigned for a separate state. The TULF contested seats only in the northern and eastern provinces and the votes obtained by them were as follows:

Jaffna (including Klinochchi) 72.1%

Mannar 51.4%

Vavuniya 59%

Mullaithievu 52.6%

Trincomalee 27.3%

Batticaloa 45.9%

Ampara 21.9%

“The remaining voters in the other districts did not support the TULF and the demand for a separate state.”

The right to full citizenship of all Tamils living in Sri Lanka

“As far as the fourth principle is concerned we do not acknowledge the right or status of any persons present here to represent or negotiate on behalf of all Tamils living in Sri Lanka. Those of the Tamil community of recent Indian origin who are commonly referred to as Indian Tamils, have their own accredited representative and government has reached certain understandings with them in regard to their problems and these do not need to be discussed here. We may state however that the government of Sri Lanka has already announced at the All Party Conference that was concluded last year its intention to grant Sri Lanka citizenship to the stateless category as soon as arrangements are made for the repatriation of the Indian Tamils who have been granted Indian citizenship.

“What I have now briefly stated is our response to the statement of the four basic principles set out in the statement of the 13th July.

“We shall presently outline our proposals.

“The implementation of any agreement reached at these talks requires as a pre-condition a complete renunciation of all forms of militant action. All militant groups in Sri Lanka must surrender their arms and equipment. All training camps whether in Sri Lanka or abroad must be closed down. Refugees wherever they may be must be permitted to return unmolested to areas which were inhabited by them prior to their disturbance and destabilization. All temples, kovils, churches, mosques and other places of worship and shrines of whatever religion damaged or destroyed shall be restored and people of all communities and religions, wherever they may be shall be allowed to manifest their religion in accordance with the guarantees in the Constitution. An amnesty for all violations of the criminal law pursuant to agitations of the militant groups will only be granted after the government is satisfied that these pre-conditions have been observed. This is the only basis on which any settlement reached here can be implemented and peace restored to our country.”

Next: Chapter 38. Thimpu Talks- Second Round (Continued)

To be posted March 11

###