by Benjamin Parkin, Financial Times, London, May 26, 2022

The country has opened talks with the IMF over a $4bn bailout with observers waiting to see how China, one of the main creditors, will react

The country has opened talks with the IMF over a $4bn bailout with observers waiting to see how China, one of the main creditors, will react

It is 10am and the queue outside a petrol station in one suburb of Sri Lanka’s commercial capital Colombo is already hundreds of people long. At the front is Malar Peter, whose family has taken turns to keep their place for 12 hours already. A few paces behind her is Padmasiri, who arrived at 1am. And right at the back of the queue stands Arumugam Annaletchumi, 50, who expects to be there for the rest of this hot, humid day.

They are all waiting for kerosene, carrying empty plastic canisters for a few litres with which to cook and burn lamps during the long blackouts caused by power shortages. Yet they are there in hope as much as anything else. There is no kerosene at the station and it’s unclear if it will arrive. For Sri Lankans, who until recently enjoyed some of the highest living standards in South Asia, such queues were rare until a few months ago. “People just want to live without problems like this,” Annaletchumi says. “This country has been robbed.”

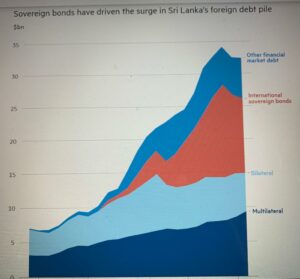

Sri Lanka this month defaulted on its overseas loans after missing interest payments on two $1.25bn sovereign bonds, the first country in Asia-Pacific to do so in more than two decades, according to Moody’s data. The latest estimates put the country’s total foreign debt at more than $50bn, with a $1bn bond maturing in July. President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s government says it has all but run out of foreign reserves and fuel, relying on ad hoc shipments to top-up supplies in the most visible manifestation of a crisis that, the Eurasia Group consultancy warns, is turning the island into a “failed” state.

After the end of a devastating 26-year civil war in 2009, the island of 22mn had the makings of an Asian economic success story. Under governments run by the powerful Rajapaksa family, annual economic growth peaked at 9 per cent. By 2019, the World Bank had classified the island as an upper-middle income country. Sri Lankans enjoyed a per capita income double that of neighbours such as India, along with longer lifespans thanks to strong social services such as healthcare and education. The country tapped international debt lenders to rebuild, becoming a key private Asian bond issuer and participant in China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Much of that progress is now in jeopardy. Some observers argue Sri Lanka’s debt crisis is the product of the hubris, mismanagement and alleged venality of political elites including the Rajapaksa family, as well as irresponsible lending on the part of its creditors.

But, on another level, it is an extreme example of the economic and political churn facing developing countries around the world as rising inflation and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine prompt higher interest rates and surging food and fuel prices globally. Within South Asia alone, countries including Nepal have imposed import restrictions in order to protect foreign reserves while Imran Khan was removed as Pakistan’s prime minister in April amid popular anger over inflation.

Sri Lanka’s “economy has been built on unsustainable debt. They were spending more than the money that was coming in,” says Hanaa Singer-Hamdy, the UN’s resident co-ordinator in Colombo. “You don’t have fuel [so] people queue for three or four kilometres waiting in the heat.”

Popular outrage has boiled over in recent weeks after a wave of retaliatory violence following attacks on anti-government protesters and the temporary imposition of a military-enforced curfew. Gotabaya Rajapaksa is fighting for his political survival after the resignation on May 9 of his once-powerful brother Mahinda as prime minister. The president has struggled to form a new cabinet with Ranil Wickremesinghe, the new prime minister, on Wednesday also taking on the role as finance minister after the post was vacant for more than two weeks.

Chinese loans to Sri Lanka, which total about $3.5bn, according to the Advocata Institute think-tank, has proved particularly controversial. While Sri Lanka owes more to private bondholders and countries like Japan, critics argue that China’s BRI loans have been extended at high interest rates for infrastructure projects that have often failed to generate returns.

Sri Lanka has begun talks with the IMF for a bailout of up to $4bn, and is preparing debt restructuring negotiations with creditors. Analysts say the talks will be closely watched to see how China — one of the largest and most important lenders to the developing world in recent years — will respond amid growing signs of financial strain in other Belt and Road participants.

A vendor works at his vegetable stall at a Colombo market. Sri Lanka has the worst inflation in Asia at about 30% in April © Buddhika Weerasinghe/FT

“Sri Lanka is a real canary in the coal mine,” says Gabriel Sterne, head of emerging markets at research group Oxford Economics. “It’s the most interesting case in years. There’s going to be lots of low-income debt crises, and the treatment of China in all that is going to be crucial.”

Postwar economic boom

Sri Lanka has many of the ingredients needed for economic and political success — from rich natural resources to strong social services and a strategic location near many of the world’s busiest shipping lanes.

But in the 1980s tension between the majority Sinhalese Buddhists and Tamils — groups that make up about 70 and 15 per cent of the population respectively — culminated in civil war when the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam launched a brutal separatist campaign amid Tamil resentment over widespread discrimination.

The conflict dragged on for more than two decades before Mahinda Rajapaksa was elected president in 2005. With Gotabaya Rajapaksa serving as defence secretary, the brothers would lead an unrelenting campaign to crush the Tigers. Government forces were accused of war crimes including indiscriminately bombing civilian areas and executing suspected militants. The Tigers were also accused of atrocities and the UN estimates that about 40,000 civilians died in the final years of the conflict, almost half the total. Mahinda and Gotabaya have been subject to sustained scrutiny from civil society groups for the alleged abuses committed under their rule, with Human Rights Watch alleging that Gotabaya is implicated in human rights abuses. He has always denied the allegations.

The end of the war in 2009 was followed by a boom in Sri Lanka’s economy. The government of Mahinda Rajapaksa tapped international bond markets and longtime ally China for debt to fund the construction of everything from roads and airports to “Port City”, an ambitious project to turn reclaimed land in Colombo into a financial hub. Tourists flocked to the island.

Yet this growth masked deep economic and social imbalances. Critics argue that the Rajapaksas shunned efforts at postwar reconciliation and continued to use ethno-nationalism to drum up their Sinhalese Buddhist base. Several debt-backed projects failed to generate a return, most notoriously a Chinese-backed port in the Rajapaksas’ home district that was ultimately handed over to Beijing on a 99-year lease. Critics say that easy money for large infrastructure projects fuelled a culture of kickbacks and corruption that became widespread in politics and business.

“The biggest issue is corruption,” says Harini Amarasuriya, an MP from the leftwing Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna party, one of Sri Lanka’s largest. “For the past 25-30 years, our economic decisions have not been made on any economic analysis but on kickbacks and commissions.”

Some members of the Rajapaksa family have been accused of wrongdoing on various occasions though they have always denied allegations and have not been convicted. Gotabaya Rajapaksa was charged in a corruption case in 2016 though the charges were dropped on grounds of immunity after he was elected president in 2019, according to media reports. He denied the allegations.

Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s 2019 landslide victory came after the Easter Sunday terrorist attacks that killed 269 people. He vowed to right an already struggling economy but instead made a series of idiosyncratic decisions that economists say tipped the island into crisis. He cut taxes sharply — eroding government revenues — and changed the constitution to concentrate power around him and his family, with several relatives also in government. He also imposed a shortlived but destructive ban on chemical fertilisers, designed to promote organic farming and save money on imports, that led to a sharp drop in crop yields.

Anushka Wijesinha, an economist at the Centre for a Smart Future in Colombo, says that Sri Lanka was considered a “donor darling” in the decades after independence, before Mahinda Rajapaksa’s government embarked on its postwar infrastructure boom. “The money [was] coming in easily from bilaterals, multilaterals and commercial loans,” he says. “Financing is not a constraint, doing the policy reforms is not a constraint, and — woohoo, bonus — the room for graft is huge.”

A series of ratings downgrades following the 2019 tax cuts locked Sri Lanka, which had never defaulted before, out of international debt markets, leaving it unable to refinance. The pandemic cut off remittances and tourism, vital sources of dollars. A poll in January by think-tank Verité Research found that only 10 per cent of Sri Lankans approved of the government. Yet Rajapaksa dismissed warnings to begin restructuring or approach the IMF for assistance until March, after protests over the growing economic hardship had spread across the island.

Sri Lanka’s reserves have fallen from $7.5bn in November 2019 to the point where finding $1mn is “a challenge”, Wickremesinghe, the new prime minister, said in an address last week. This has meant shortages of not only fuel but food and medicine, with hospitals forced to postpone surgeries. The country has the worst inflation in Asia at about 30 per cent in April and the currency has almost halved in value since it was floated in March.

The UN Development Programme says that nearly half the population is in danger of falling below the poverty line, and warns of a looming humanitarian crisis as the urban poor and former middle class begin to cut back on meals.

WN Thilini lives with her two-year-old daughter in a low-income Colombo neighbourhood. She says she has stopped giving milk to her child and that they now eat mostly rice, dhal and grated coconut. The 38-year-old says she has enough food and fuel in the house for a couple more meals, before she too will need to join a queue.

“Most people are down to one meal a day”, says her neighbour, Mohammad Akram, “but are embarrassed to admit it.”

A default test case

On top of Rajapaksa’s mismanagement and Covid, observers say the final trigger for Sri Lanka’s default was the war in Ukraine — a worrying example of the aftershocks of the conflict for low- and middle-income countries. Some, including Belize and Zambia, had already defaulted in the wake of the pandemic.

In addition to depending on imported energy and staples such as wheat, the conflict has hit Sri Lanka in unexpected ways. Russia and Ukraine were the country’s first- and third-largest tourist markets in early 2022 respectively. Russia was also the second-largest buyer of Ceylon tea, Sri Lanka’s main goods export.

The island’s default could have significant geopolitical ramifications. Its strategic location in the Indian Ocean has long made it an arena for jockeying between countries such as India and China, arch-rivals who have used combinations of easy credit and diplomatic pressure to secure their interests on the island.

Critics of Chinese activity on the island accuse it of using BRI projects to ensnare the country in a “debt trap”, allegations that it denies. Yet while China has so far rejected Sri Lanka’s requests to restructure its outstanding debts, India has sought to cement its primacy on the island, offering a series of credit lines, debt swaps and other assistance measures that it [India] says total about $3.5bn.

Sri Lanka’s upcoming debt restructuring negotiations are being viewed as a case study for how China works alongside other creditors such as private bondholders, given the rise of Chinese lending in Africa and Asia.

Analysts say that in countries such as Zambia, as well as Sri Lanka, it remains unclear whether Chinese lenders — which includes the government as well as state banks — will be willing to accept losses on their loans or look to enforce claims for full repayment.

Analysts say that in countries such as Zambia, as well as Sri Lanka, it remains unclear whether Chinese lenders — which includes the government as well as state banks — will be willing to accept losses on their loans or look to enforce claims for full repayment.

Zambia’s restructuring has shown “there’s somehow this expectation that [Chinese lenders] would be senior creditors,” and therefore prioritised for repayment, argues one London-based fund manager, who holds Sri Lankan bonds.

The fund manager argues that had Rajapaksa started the restructuring process earlier, when Sri Lanka had more foreign reserves left, creditors could have recouped larger amounts. “What would have been a fairly mild restructuring process is now a more complicated one.”

The success of any restructuring is likely to be tied to the IMF programme. Any assistance package will take months to negotiate and, while Sri Lanka has already been through 16 IMF programmes in its 74-year history, it has only completed nine. International groups also warn that the reforms the fund is likely to demand, such as reversing Rajapaksa’s 2019 tax cuts and reducing energy subsidies, could exacerbate the suffering without adequate protections for vulnerable populations.

Improvement is “not going to come immediately,” warns Nalaka Godahewa, an MP from Rajapaksa’s ruling Podujana Peramuna party. “It’s going to be difficult because nothing much is going to change [in the short term].”

It is unclear whether Rajapaksa and his government can survive even before implementing a series of potentially unpopular economic reforms, prompting analysts to warn that the island could face prolonged political instability.

“To go into an economic restructuring, you need political stability. This is now challenging,” says the UN’s Singer-Hamdy. “The most important is how you discuss with the creditors now, in terms of agreeing to a haircut. This is [what] will help . . . Everybody is waiting to see how the government will negotiate the restructuring with the creditors.”