Essaying the Folk Heroes in Films and Becoming One

by Sachi Sri Kantha

MGR (in make up) lifting Lena chettiar, probably around 1960

Fellow MGR biographer R. Kannan’s observations, on Part 70, received on Mar 27th , was as follows:

“The article was fascinating. I did not know anything about Kalai Arasi and was quite taken with the fact that it was a sci-fi movie in Tamil and with MGR that early on. I would have never imagined something like that if not for your article.

In the song, Athisayam kanden and the K plan, are you suggesting that there is a link? Thank you.

My response to Kannan’s thoughts, sent on Mar 28th was,

“About ‘Kalai Arasi‘ movie. I should have written this chapter earlier, but have to insert it, as an after thought, to mark the 60th anniversary of it’s release. I did check your book, and you had mentioned in a footnote to chapter 4, (two movies – Raja Thesingu and Kanchi Thalaivan) that MGR and Bhanumathi came together after their fall out in Nadodi Mannan – but inadvertently omitted ‘Kalai Arasi‘.

As for your query about Pattukottai Kalyanasundaram’s lyric and Kamaraj plan of 1963, no I didn’t think about a link between the two. My main focus was on finding an example for readers to comprehend Otto Friedrich’s observation that any art form is remembered for long time, while the words/deeds of politicians are soon forgotten. Tamil cinema song is a 20th century art form, created by many brains. If the lyric is meaningful, set by a music maestro and sung by a great singer to be acted by a favorite star, the totality of this art form lives forever. This has become true for so many movie songs, even if the movie in which they are featured were flops at the box office. A good example is Kalyanasundaram’s lyric ‘Unmai Orunaal Veliyaahum’ in ‘Paathai Theriyuthu Paar’ movie, sung by Tiruchi Loganathan. (the link is https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HSVoeY-Flgo), and other songs in the same movie, such as ‘Thennan keetru Oonjalile’, Jayakanthan lyric, sung by P.B. Srinivas and S. Janaki.

There are two additional points, I note here.

First, Kalyanasundaram had died in 1959, before Kamaraj Plan. So, he simply couldn’t have imagined about this political strategem of Congress folks. He was also a sympathizer of Communist ideals. Secondly, it was Morarji Desai’s gripe that the Kamaraj Plan was not his ‘original’, but he was merely acting as a conduit of Nehru, who had wished to propel Indira’s fortune ahead of Congress Party’s old codgers like Morarji, S.K. Patel and Nanda, so as to sideline these guys in the prime minister sweepstakes. Now, after 60 years, who among the Indian politicians will sacrifice their CM positions willingly, according to Kamaraj Plan?”

Actress Rajasree’s experience in working with MGR

After reading Part 70 of this series, my pal (Nithipalan) and MGR fan of school days in 1960s, helped me in retrieving the Youtube link of a 14 min. interview in 2017 of actress Rajasree’s experience in working with MGR and Bhanumathi for five years in the Kalai Arasi movie (Part 70). The link is as follows: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tfkaAkNS7Go

She also confirms my estimate five years (and not seven years, as the dyspeptic critic for the Kalki magazine had written; see, Part 70) were spent in producing the first space fiction movie in India. In the interview, Rajasree also confirmed that the shooting picked up, only after MGR had recovered from his 1959 leg injury. She had described the shooting sequence of the duet song in ‘Space’, when she was around 16 or 17. Nee irupathu inge un ninaiviruppathu enge (Now you are here – but your thoughts are where)– singers Sirkazhi Govindarajan and P. Susheela, lyricist N.M. Muthukoothan. The Youtube link is https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uSJbckrI-zI

In the absence of any other recorded oral history related to the production of Kalai Arasi movie, I’d consider that this interview by a participant actress deserves historical preservation.

In this chapter, I revisit two more MGR – Bhanumathi starrers of 1950s, namely Madurai Veeran (1956) and Raja Desingu (1960), both produced by S.M. Letchumanan (Lena) chettiar, under Krishna Pictures label. The plots of both movies were based on folk heroes passed along for generations via oral tradition in Tamil Nadu. Whereas lyricist Pattukottai Kalyanasundaram had died during the production of the Kalai Arasi (1963) movie, of the two movies to be covered here, comedian actor and MGR’s mentor N. S. Krishnan (1908-1957) had died in 1957, during the production of Raja Desingu movie. Though the scenes shot before his death were included in the final edit of the movie, the death of such an influential negotiator of conflicts involving MGR was considered as a bad omen for this movie’s completion.

MGR – a 20th Century Folk hero in Tamil Nadu

How MGR was able to succeed in politics and become the Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu, within 5 years after founding his own party? Why his equally competent contemporary rival actors in Tamil Nadu and other states of India [excluding N.T. Rama Rao (NTR), in the Andhra Pradesh] failed to emulate MGR’s success in politics? In case of NTR, it could be said, he portrayed God Krishna in many of his movies, and came to be identified as a ‘real God’ by the gullible fans. But, this reasoning wouldn’t work for MGR, because after he gained a firm foothold in the Tamil movies since 1950s, by choice MGR avoided playing ‘God’ characters.

A few, including MGR’s pals like Karunanidhi and Kannadasan, had assigned chief credit to MGR’s ‘Man Friday’ R.M. Veerappan (b. 1926), who had managed to protect and promote MGR’s ‘clean image’ to the masses in politics. But, I find this rather unconvincing, for more than one reason. First, it assumes that the Tamil Nadu voters were ignoramuses who couldn’t distinguish the kernel from the chaff. Secondly, if Veerappan was such a great ‘manager’, how he failed miserably in the post-MGR period during 1988-89, in his inability to hold MGR’s flock together in the party and promote the same magic with MGR’s widow Janaki Ramachandran. Thirdly, why Veerappan himself couldn’t become the Chief Minister, using the same talent and magic, which Veerappan’s friends assume that MGR didn’t possess? I do not doubt Veerappan’s managerial skills in molding MGR’s persona to a degree, but he sadly lacked the leadership skills. The truth is, by his own character, will, discipline and intent to succeed against odds, MGR himself appealed to the masses; and Veerappan’s contribution had been exaggerated.

Appropriate at this juncture is a comment by reputed American film critic Pauline Kael (1919 – 2001), who wrote about the extraordinary audience rapport some movie actors were blessed with. She wrote,

‘ There are certain actors who have such extraordinary audience rapport that the audience does not believe in their villainy except to relish it, as with [Marlon] Brando; and there are others, like [Paul] Newman who in addition to this rapport, project such a traditional heroic frankness and sweetness that the audience dotes on them, seeks to protect them from harm or pain.’

In Hollywood, one may add Jimmy Stewart (1908-1997) also in this category. And MGR was the one and only Indian actor, who earned such a extraordinary audience rapport, among his contemporaries. Among Japanese actors, only Kiyoshi Atsumi (1926 – 1996) had it. This ‘extraordinary audience rapport’ is not related to best acting. As professionals, all had their shades of excellence. It’s something of a sincerity aura, few talented actors continued to project in their performances for years, even decades, despite occasional flops in the box office. Why these actors were able to reach this strata in audience appreciation? My theory is – all played the role of idealistic folk heroes convincingly in their respective cultures, at specific stage of their careers.

I list below 12 distinct roles, in which MGR excelled himself, for half a century, without parallels.

✰Drama actor in Tamil (1930s-1950s)

✰Cinema actor in Tamil (1936-1978)

✰Exponent of ancient Indian martial arts (1940s-1970s)

✰Founder of a Tamil drama troupe (1950s)

✰Philanthropy (1950s-1987)

✰Talent spotter and promoter of lyricists, playback singers, comedians, actresses and script writers (late 1950s to 1970s)

✰Film studio owner (Sathya Studio, 1960s-1987)

✰Twice elected member of Tamil Nadu state legislative assembly (1967-1977)

✰Tamil writer – articles and autobiography (1960s-1972)

✰Founder leader of a successful political party (1972-1987)

✰Three times elected Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu state in India (1977-1987)

✰Patron of Eelam Tamil liberation movement (1984-1987)

Role as a Studio Owner

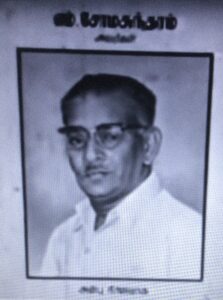

Screen grab – title credit to producer late producer M. Somasundaram, in Arasilankumari (1961) movie

In the previous 70 chapters, I had covered to a limited extent, nine among the first ten roles played by MGR. The studio owner role, was not touched, due to lack of authentic details in my hand. Even MGR’s previous biographers in English, including M.S.S. Pandian and Kannan also failed to allocate space to this particular role of MGR. But, to his credit, Kannan had noted the influence of the contribution of Jupiter Pictures in the elevation of MGR’s career in hero roles of 1940s. Additional meager details gathered are given here.

Jupiter Pictures, established in 1934, and owned by M. Somasundaram chettiar (tagged as Jupiter Somu, (~1907 – 1960) and S.K. Mohideen was a notable movie production house located first in Coimbatore, and later moved to Chennai. In a span of 25 years, they produced or sponsored 35 Tamil movies; quite a number of these were ‘big hits’. MGR had received first recognition as a hero in Rajakumari (1947), produced by Jupiter pictures. Not only MGR, it was Somasundaram and Mohideen who opened the doors for young Karunanidhi’s entry into Tamil movie world as a script writer for the Rajakumari movie. Apart from Karunanidhi, other talented artists including M. N. Nambiar, Kannadasan, A.S.A. Samy, A. Kasilingam, M.M.A. Thirumugam, and M.S. Viswanathan who later came to be noticed prominently in MGR movies had training at the Jupiter Pictures compound. Mohideen had died in 1954, few days after the release of Manohara movie (a Sivaji Ganesan starrer, with fiery dialogues scripted by M. Karunanidhi). Subsequently his son S.K. Habibullah took his father’s place. The other founder owner Somasundaram died in Nov 17, 1960. It was reported that his mentally unstable daughter also died within few days, in the shock of losing her father. In an interview before his death, A. Jagannathan (1935-2012) from Tirupoor, who directed one of MGR’s hit movies, Idhayakani (1975, Heart Fruit) had talked about the influence of Jupiter Pictures in late 1950s. The Youtube link is https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-S2R2BoFWXs

Movie director A. Jagannathan

As an expression of gratitude to the movie mogul Somasundaram who offered him the ‘big break’ in 1947, and to settle the debts incurred, the Neptune studio leased by Jupiter Pictures in Chennai, was purchased by MGR in 1961 and renamed as Sathya Studio by him, in honor of his mother. The last movie under the ‘Jupiter’ banner Arasilamkumari (1961, The Princess), with MGR – Padmini pair, was released after Somasundaram’s death. The fate of this movie, directed by A.S.A. Samy (who also directed MGR in his first hero role, 1947) and scripted by Karunanidhi, was sealed due to a casting blunder. MGR and Padmini were cast as siblings, and MGR’s love interest was Rajasulochana.

Veerappan became the executive of Sathya studio and produced six MGR movies with ‘Sathya Movies’ banner, from 1964 to 1975, at frequent intervals:

Deivathai (1964), ‘Naan Anaiyittal’ (1966), ‘Kavalkaran’ (1967), ‘Kannan En Kathalan’ (1968), ‘Rickshakaran’ (1971) and ‘Idhayakani’ (1975) – all were of ‘MGR formulaic’ variety and successful at the box office. According to Kannan, Sathya studio became a convenient hub of political activities for MGR’s supporters, after MGR’s expulsion from DMK in October 1972.

Folk Hero

75 years ago, American sociologist Orrin E Klapp received his Ph. D degree from the University of Chicago, for his dissertation ‘The Hero as a social type’. Subsequently, he published his research in a series of papers on this vital theme of heroes, and their mirror image – villains. One such study was on folk heroes. Klapp’s formulation of how a folk hero evolves in a culture depends on their altruistic roles, ‘because the act performed by the hero is of benefit to someone besides himself, involving even personal sacrifice or martyrdom’. And Klapp identified three types of folk hero: the defender or deliverer, the benefactor, and the martyr. There is also a negative folk hero. In Indian movies, quite a number of MGR’s contemporaries like Pramathesh Barua, Kundan Lal Saigal, Dilip Kumar and Akineni Nageswara Rao had essayed the role of Devadas, based from a Bengali novel of 1917, by Sarat Chandra Chatterjee (1876-1937). This Devadas persona was that of an alcoholic wastrel, patronizing a prostitute. MGR would never play such a role for applause and pity, because the deeds done by this character was against his beliefs and ideals of a valued folk hero.

The most popular fitting title in Tamil, with which MGR was known is ‘Makkal Thilagam’ [literally, an ornament of People], aka, a folk hero. Contrastingly, his junir pal and rival in Tamil cinema, Sivaji Ganesan is known as ‘Nadikar Thilagam’ [literally, an ornament of Actors].

As listed above, in 12 inter-linked distinct roles, MGR was able to achieve the status of folk hero among the Tamils. And let me focus on the two folk hero roles MGR played in the second half of 1950s – that of Madurai Veeran (1956, Hero of Madurai) and Raja Desingu (1960, Raja Te Singh). Recently, in an article that studied the history and the folk story of Raja Te Singh, Suganthy Krishnamachari opined that ‘the MGR film Raja Desingu was also mostly based on the ballad, with a few changes.’ Why these changes has to be made, to satisfy MGR’s doubts will be described later in this chapter.

In 1978, Stuart Blackburn then affiliated to the University of California, Berkeley published a paper on the folk heroes of Tamil Nadu. His analysis included Madurai Veeran and Raja Desingu – two specific roles MGR had essayed in film. Presented below are the paragraphs from Blackburn’s study, which describes the stories of these two folk heroes. [the spellings of folk heroes are retained, as in the original.]

“Viran is an untouchable who elopes with a higher caste woman whose father, a local king, sends an army to retrieve her. Viran defeats them and is called to Madurai to defend against robbers who are plundering within the walled city itself. This he does and is honored. But then the story takes a strange twist. Viran is caught making off with one the King’s women and is summarily quartered. Later, learning who it is that he has ordered quartered, the repentant King requests a goddess to restore his limbs. This is done, but Viran is unhappy and declares that he must die as he has sinned in a previous birth. Later he is unhappy because propiatory rites are not performed satisfactorily. On the goddess’ advice, he communicates this to the king in a dream and the latter arranges a daily worship and Viran becomes deified.”

“The story of Tecinku Rajan is that the Mughal Emperor in Delhi invites all his tributaries to his court to try to mount a celestial, magical, swift horse. The father of Tecinku goes and, with the others, fails and is consequently jailed. When Tecinku attains maturity he goes to Delhi, successfully rides the horse and wins his father’s release. Tecinku returns to the south and becomes ruler of a petty kingdom under the Emperor and his subordinates in the area. Later the Emperor sends an army against Tecinku because he has not paid tribute. Tecinku is valorous in battle, but because his best friend, a Muslim, is treacherously killed, he loses heart and kills himself.”

Prior to Blackburn’s version, prominent Tamil folklorist N. Vanamamalai had given a version, that was followed in the plot of Madurai Veeran movie, as opposed to the version offered by Blackburn. Vanamamali’s version is as follows:

“Madurai Veeran kathai [story] is also a story of love and marriage between a Chakkli hero Madurai Veeran and the daughter of Naik nobleman, Bommi. This marriage enrages the Naik nobleman who rallies his castemen to fight against the ‘upstart’ Chakkli of the lowest caste. Bommi’s father is killed in battle and the loves escape to Trichy. Madurai Veeran finds employment in the army of the Naik ruler of Trichy. On the request of the famous Thirumalai Naick of Madurai, the Naik of Trichy sent Madurai Veeran on a raid to annihilate the robber gangs of Alagarmalai that pester the Pandyan kingdom. Madurai Veeran successfully destroyed the gang of robbers and was richly rewarded by Thirumalai Naick. But he soon got into trouble with the ruler since he was caught in an attempt to entice and abduct away Vellai ammal, the favorite sweetheart of the Naik. The Naik unmindful of the services of Madurai Veeran ordered him to be quartered. Bommi and Vellai ammal who had fallen in love with him burn themselves on the funeral pyre of Madurai Veeran.”

Comparison between Madurai Veeran (1956) and Raja Desingu (1960) movies

Comparising two folk hero movies of MGR produced by Lena chettiar

Screen grab from Madurai Veeran dance sequence – MGR and Padmini

I have prepared a table comparing the details of Madurai Veeran and Raja Desingu movies (check the pdf version above) and both movies were produced by Letchumanan chettiar (popularly known as Lena chettiar). Whereas Madurai Veeran was a box office hit, Raja Desingu flopped. But, as the table shows, all the lead players (MGR, Bhanumathi, Padmini, T.S. Balaiah, N.S. Krishnan and his wife T.A. Mathuram), lyricists, Kannadasan as script writer and G. Ramanathan as music director contributed to both movies. Both movies also had folk dance/song sequence of MGR and Padmini pair. Whereas for Madurai Veeran, the singers for this folk song were T.M. Soundararajan and Jikki, for Raja Desingu, Sirkazhi Govindarajan and P. Leela sang the gypsy song. It is a given that Padmini is a great dancer, but MGR matched Padmini’s steps diligently, despite an age difference of 15 years. D. Yoganand directed Madurai Veeran, and T.R. Ragunath directed Raja Desingu. The running length for both movies was also nearly the same.

Echu pizhaikum thozhile sari thana – Madurai Veeran movie

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mIxQ7uY4eB4

Kananguruvi kaatupura – Raja Desingu movie

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bttPZOAroiI

Screen grab from Raja Desingu movie- 1. Padmini, 2 – MGR, 3 – Balaiah and 4 – M.G.Chakrapani

As a prelude to the Raja Desingu movie song, MGR and Padmini spoke in the Indian gypsy language. The guy who plays the role of the king in this song sequence, was MGR’s elder sibling M.G. Chakrapani.

As to the delay in completing the Raja Desingu movie and it’s failure in the box office in 1960, despite the similarities to Madurai Veeran of 1956 mentioned above, many have wagged their tongues on the bad blood between producer Lena Chettiar and MGR. But, to comprehend MGR’s thoughts, one has to read his autobiography and that of Ravindar’s memoir.

It is a certified fact that established actors and directors demand ‘total control’ of the movie to which they contribute their skills, energy and time. In the annals of movie making, the list is long – Chaplin, Brando, Hitchcock, Kubrick, Kurosawa etc. They hate interference from the producers and wouldn’t dance to the whims of producers. After his apprentice years of over two decades, MGR had joined this clique.

MGR’s version of the conflict with Lena chettiar

According to Ravindar (MGR’s writing assistant), “After Madurai Veeran, Lena chettiar produced Raja Desingu. During story discussion, MGR said, ‘the basis of this plot is wrong. Father attempts to control a wild horse, and fails. Twenty years later, son makes his attempt to revenge the horse. But the horse would have aged by that time. Should MGR has to do this to an aging horse?’ Chettiar couldn’t answer. He only responded: ‘I had advertised and received money [from the financiers]. Whatever it is, kindly proceed along.’ Half-heartedly MGR agreed. ‘I’ll try. But cannot gurantee a hit.’ Because as he was not pleased with this plot with double role, MGR looked for another story for rhis own production.”

Ravindar continued,” [Following June 1959 accident in the drama stage that] broke his leg, when Lena chettiar visited Vauhini studio and asked him ‘How are you?’ Has your leg recovered now?’ MGR replied ‘You can check’, and lifted Lena chettiar. After that, [he] participated in the shooting of Raja Desingu. From the beginning, MGR didn’t like the story plot. He completed the movie half-heartedly. But, the movie failed at box office.

Another movie ‘Madappura’ [Balcony Pigeon] that was released around the same time also didn’t have success, as expected. After these lessons only, MGR decided strongly to choose to dictate his terms to the producers. [He said] ‘Hereafter, I’ll not bend to the conveniences of the producer. I’ll chose the story or I’ll have to be given rights to decide the story as per my wish. One can work with those who knows the stuff. One can also work with those who don’t know the stuff. But, one shouldn’t work with those who are ignoramuses, but pretend to know.”

MGR had described his sentiments on filming Raja Desingu, as follows: ‘In a text book authored by late Mr T.P. Krishnaswamy Pavalar and approved by the government, it is written that the father of Raja Desingu first loved a Muslim woman and after she had given birth to a son, then after his legally married Hindu wife had given birth to a son, had requested his first wife (Muslim) to leave for a foreign country by offering her cash. She rejected such offer and left. Later, his son [born to Muslim woman] became his rival. We believed that if this book has been approved by the government as a text book for children, it is reasonable evidence and has support for this story, and filmed Raja Desingu. But still, it is not allowed for screening in Malaysia. The reason being, ‘it is assumed that, it hurts the sentiments of Muslims…’” Even in Ceylon, if I’m not wrong, this movie was first banned, and then I guess was allowed for limited screening for days – if not weeks!

In his autobiography, MGR had acknowledged that it was Lena chettiar, who had arranged him for the starring role, in Malai Kallan (1954, The Dacoit of Mountain) produced by Sri Ramulu Naidu of Pakshiraja studio – his first pairing with Bhanumathi, as a hero. As for the history of Malai Kallan contract MGR received, biographer Kannan presents an alternate version. That Sri Ramulu Naidu had first approached Sivaji Ganesan and the latter had recommended MGR’s name to Naidu, as he was busy with his schedules in Chennai. ‘The next day, Sriramulu Naidu met MGR and signed him up.’ In my view, Kannan’s cited source of this alternate version is rather dubious – a book by one P. Deenadhayalan on Sivaji Ganesan’s career, published in 2006! The author of this book, a fan of Sivaji Ganesan probably, had written fiction, without verifying that MGR had acknowledged in early 1970s, how he came to be contracted for Malai Kallan movie, via Lena chettiar. MGR had recorded as follows:

“One day Mr. Lena chettiar came to my house. Before that, he had never come. ‘Thamby, I had recommended you to a movie. Will you act? What do you say?’

I responded with a question. ‘[Is it a] trouble producer?’

The anger of Mr. Lena chettiar was beyond limit. ‘Hey! We are the one who should ask, is it trouble actor? You are asking me such. What a courage?’ was his reply.

Then, I mentioned my recent experience with ‘Genova’ movie producers.

He responded, ‘You have to act in the Malai Kallan movie, to be produced by Pakshiraja films. Sriramulu Naidu is the director.’…..

After hearing the name of Mr. Sriramulu Naidu, I refrained from saying anything.”

Though MGR had assigned Malai Kallan movie as the 4th important movie in his career elevating him to the top rank as a hero, he had omitted Madurai Veeran’s (1956) contribution for his success, probably because his chemistry with Lena chettiar was a troubled one.

Cited Sources

Anon: Man who shored up MGR’s film career is no more. Times of India, Oct 8, 2012 https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/coimbatore/Man-who-shored-up-MGRs-film-career-is-no-more/articleshow/16716784.cms (accessed May 10, 2023)

Stuart H Blackburn: The folk hero and class interests in Tamil heroic ballads. Asian Folklore Studies, 1978; 37(1): 131-149.

Randor Guy: Raja Desingu. The Hindu (Chennai), Aug 15, 2015.

Jupiter Pictures – Wikipedia article. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jupiter_Pictures (accessed May 10, 2023).

Pauline Kael: I Lost it at the Movies, Bantam Books, New York, 1966, pp. 70-71.

Kannan: MGR – A Life, Penguin Random House India, Gurgaon, Haryana, 2017, 60-65.

Orrin E. Klapp: The creation of popular heroes. American Journal of Sociology, Sept 1948; 54(2): 135-141.

Orrin E. Klapp: The folk hero. Journal of American Folklore, Jan-Mar 1949; 62 (243): 17-25.

Orrin E. Klapp: Hero worship in America. American Sociological Review, Feb 1949; 14(1): 53-62.

Orrin E. Klapp: Heroes, villains and fools, as agents of social control. American Sociological Review, Feb 1954; 19(1): 56-62.

Suganthy Krishnamachari: Where the ballad scores over history. The Hindu (Chennai), May 7, 2020. https://web.archive.org/web/20210414135334/https://www.thehindu.com/society/history-and-culture/where-the-ballad-scores-over-history/article31525509.ece [accessed May 11, 2023]

Aranthai Narayanan: Thamizh Cinemavin Kathai, New Century Book House, Chennai, 2nd ed., 2008, pp. 650-652 (in Tamil)

MGR: Naan Yaen Piranthaen? Vol. 2, Kannadasan Pathippagam, Chennai, 2014, pp. 991-992, 1272. (in Tamil)

Ravindar: Pon Mana Chemmal MGR, Vijaya Publications, 2009, p. 24, 57. (in Tamil)

Theodore Baskaran: The Eye of the Serpent: An Introduction to Tamil Cinema, Transquebar Press, Chennai, 2013, pp. 126-127.

Vanamamalai: Studies in Tamil Folk Literature, New Century Book House Pvt Ltd., Madras, 1969, p. 114.

*****

As mentioned by Dr. Sachi, “The truth is, by his own character, will, discipline and intent to succeed against odds, MGR himself appealed to the masses;”

NTR had the advantage of God image, but MGR got the God image by his philanthropy.

Even now his fans visit his birth home in kandy and worship there:

https://www.bbc.com/tamil/articles/cg3n1drk8pdo?fbclid=IwAR3aGmI3nbHSIEO9U-KzHLUjJWoKWb1yrmq3HonwjI7ZjC9BPHpVn8Vp4K8