by Sachi Sri Kantha, January 2, 2026

Rajadurai being introduced to then British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in 1985

Chelliah Rajadurai (1927-2025), the ‘charmer’ among Eelam Tamil politicians, bid adieu on Dec 7, 2025, after a lengthy mortal life of 98 years and 5 months. He was garlanded with quite a few sobriquets, like ‘sollin chelvar’ (Wealthy in Words) and ‘Ezhil Thamil Aalar’ (The ruler of elegant Tamil), by those who adored him. These fitted with his God-blessed talents, if not character. As I had reminisced in a piece, posted last year, [https://sangam.org/chelliah-rajadurai-reminisces-on-mgr-and-b-saroja-devi-visit-to-ceylon-in-1965/], my preference is the single word ‘charmer’ in Sanskritized Tamil, it means vaseeharan. Otherwise, how could he literally ‘rule’ [i.e., elected] the Batticaloa constituency from 1956 to 1988.

Of course, Rajadurai’s tenure as a MP was aided by plus 2 year extension offered by Sirimavo Bandaranaike’s unappreciated decision to extend parliamentary period in 1975, and another plus 6 year extension by a dubious referendum by President J.R. Jayewardene in 1982. Nevertheless, Rajadurai was elected for Batticaloa for a record six times, despite severe odds pushed against his candidacy – by Tamils as well as Muslims. Born in July 27, 1927, he was elected for the first time in the Federal Party ticket, at the age of 28 years and 9 months in the April 1956 general election. An equally comparable performance in the North, was that of Rajadurai’s Federal Party colleague V.N. Navaratnam (1929-1991) in Chavakachchery constituency. He was only 26 years and 10 months old. I had heard the story that Navaratnam was a last minute substitute candidate for one of his kins (originally chosen by the Federal Party), who had died prior to the nomination date.

But there are differences between the victories of Rajadurai and V.N. Navaratnam. First, Chavakachchery had remained a single member constituency from 1947 till 1977. But Batticaloa was switched to double member constituency from 1960 to 1977. Secondly, while Chavakachchery’s ethnic Tamil base was 91.8% in 1946 and 97.3% in 1976, Batticaloa’s ethnic Tamil base was 52.6% in 1946 and 61.1% in 1976. As such, Rajadurai to become a winner in 6 elections (and being placed 1st in 5 consecutive elections) from 1956 to 1977, should have gained a degree of support from Muslim constituents as well.

This will be a multi-part tribute to Rajadurai, In Part 1, I record the facts on Rajadurai’s electoral success that enabled him to be a Tamil legislator, from 1956 to 1988. Prior to Rajadurai’s first electoral victory in 1956, for comparative reason, the previous two general election records (1947 and 1952) for the Batticaloa constituency in post-Independent Ceylon, deserves a check as well.

Batticaloa constituency in post Independent Ceylon

Batticaloa constituency is somewhat unique of a blend in the island, with Tamil, Muslim and minority Sinhalese ethnics. Between 1950 and 1976, there were marked population shifts, with increasing population of Sinhalese ethnics, which led to the formation of a separate constituency Amparai in 1960. Batticaloa was no.56 in the electoral list, among 89 constituencies for the 1947, 1952 and 1956 elections; and, it was a single member constituency. During the 1960 (two elections in March and July), 1965 and 1970, Batticaloa became no. 90 among 145 constituencies and changed into two member constituency, to accommodate one Tamil and one Muslim member. Also, strategically to accommodate the representation of Sinhalese ethnics, a separate Amparai constituency was created in 1959 and given no. 91. Then, in the 1977 election, Batticaloa was given no. 97 among 160 constituencies and the two member constituency was retained to accommodate one Tamil and one Muslim member. Amparai was given no. 99. Subsequently, Amparai was tagged a Sinhalese name Digamadulla.

In 1946, population wise split among the ethnics in Batticaloa constituency was:

Tamils (Ceylon and Indian) 52.6%, Muslims (Ceylon and Indian) 28.7%, Sinhalese 13.0%, ‘unclassified’ (other ethnics including Burghers, Malays) 5.7%. Total electorate for 1947 was 27,409, for 1952 was 24,947, and for 1956 was 29,486. In 1959, population wise split among the ethnics in Batticaloa constituency changed to: Tamils 56.5%, Muslims 36.0%, Sinhalese 5.2%, ‘unclassified’ 3.5%. Total electorate for 1960 was 37,832. This was after the split to form Amparai constituency for Sinhalese ethnics. For the Amparai constituency, the ethnic population in 1959 was Sinhalese 90.9%, Tamils 6.3%, Muslims 2.0%, ‘unclassified’ 0.8%. Total electorate was only 19,535.

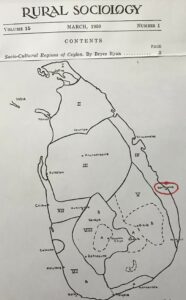

Bryce Ryan’s sketch of placing Batticaloa (Eastern Province) in 1950

American scholar Bryce Finley Ryan (1911-2005) served as the first professor in sociology at the University of Peradeniya. In his paper entitled ‘Socio-cultural regions of Ceylon’ paper published in Rural Sociology journal (1950), Ryan had split the ethnic composition of the island into eight distinct regions (‘Areas’). His description of Area IV as ‘The Muslim-Tamil East Coast’ remains as a historical document, that provides pointer to the mid-1950s influx of the Sinhalese ethnics due to state induced colonization schemes. I provide below first two and last two paragraphs in this section, of what Prof Ryan had written:

“Lying between the dense jungles and the eastern beaches is a narrow strip of the coastal plain containing almost equal proportions of Ceylon Moors and Ceylon Tamils, with slight sprinklings of others. Rainfall here is all but limited to a single season, the North-East monsoon, and agriculture, mainly paddy, is dependent upon direct rainfall, river irrigation, and tanks. The most distinctive feature of community organization is the occurrence of phenomenally large villages of cultivators. While other communities exist, both as agriculturists and as craftsmen, there is a pronounced concentration of population in the great agricultural villages. A number of these have populations of 10,000 persons or more.

Nor are these large communities dispersed in their settlement in any degree. The village is closely packed, to the point of unhygienic proximity. Some of these settlements are almost exclusively of a single nationality, others are mixed. Where mixed, the Moors and the Tamils live as separate ‘communities’, ecologically and socially segregated in all but economic affairs. There has been a tendency for the Muslim Moor to become the landed proprietor and the Tamil a landless farm laborer….

High concentration of paddy land ownership and extensive utilization of hired labor, as well as sheer density of population, have produced a high development of commercialized and trading relationships within the village. Although the ‘trade area’ is practically confined to the village proper, the thatch-hut shopping center is as much, and probably considerably more, and the core of village life as is the town square is a southwestern American community. Here are the ‘tea shops’, the hardware and cloth merchants, the money lenders, the ubiquitous boutiques, the village market, and possibly a recreation center. The Mosque and the Hindu temple will not be far off.

Ecologically this is no peasant agricultural village it is a city of farmers. Socially it is peasant, but in no sense a simple and undifferentiated village of cultivators. It is a community completely differentiated by ethnic and religious differences, as well as by economic facts, by caste, and by caste-non caste composition. Culturally it is still a folk community; most of its people are hand workers of the soil all live in strong familistic associations; all are closely bound by their traditional cultures few have either personal or secondary experience with things urban.”

Rajadurai’s electoral performance

Please note that, Prof Ryan had NOT mentioned about Sinhalese ethnics and Buddhist vihares. Now, to the statistics of electoral records of Batticaloa constituency in the 1947, 1952, 1956, 1960 (two elections), 1965, 1970 and 1977 general elections.

Abbreviations used: Batticaloa Tamil Speaking Front, Federal Party (FP), Independent (Ind), Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP), Tamil Congress (TC), and United National Party (UNP).

1947 – single member constituency

Total electorate 27,409; Total votes polled 13,712 (50.0%)

Ahmed Lebbe Sinnalebbe (UNP) 4,740

K.V.M. Subramaniam (Ind) 3,395

R.B. Kadramer (Ind) 2,313

N.S. Rasiah (Ind) 2,226

Rasiah (Ind) 714.

Vote margin of the winner 1,345.

What is interesting in this election result is that, voting percentage was a poor 50%, and a Muslim candidate nominated by the UNP got elected, due to splitting of Tamil votes among 4 Tamil candidates, who contested as Independents. In his memoir, Rajadurai mentions that during 1947, he was still in school. [This particular fact, I found rather peculiar. He was born in July 27, 1927. The Batticaloa election was held on Sept 1, 1947. This makes him 20 years and one month old!. He also mentions that he couldn’t vote. At that time, voting age was set at 21.] He mentions that the Tamil candidates were lawyers, and K.V.M. Subramaniam and Mr. Rasiah were rich men. But, he rooted for lawyer Robert Bruce Kadramer. His father and his school principal, teachers and those in his locality supported the candidacy of K.V.M. Subramaniam. Due to this discrepancy, whenever he visited the house of Kadramer, villagers turned suspicious eyes of his visits.

1952 – single member constituency

Total electorate 24,947; Total votes polled 19,640 (78.7%)

R.B. Kadramer (Ind) 11,420

Ahmed Lebbe Sinna Lebbe (UNP) 7,960

Vote margin of the winner 4,805

About this election, Rajadurai had reminisced, he attempted to pull Kadramer to contest as a nominee of the then newly formed Federal Party. But, Kadramer was reluctant to contest under Federal Party label, for the reason that Batticaloa folks will not support his candidacy for a ‘party of Jaffna people’.

1956 – single member constituency

Total electorate 29,486; Total votes polled 18,156 (61.6%)

Rajadurai (FP) 9,300

Ahamathulebbe (Ind) 7,124

R.B. Kadramer (BTSF) 1,296

A, Thavarajah (Ind) 148

Vote margin of the winner 2,176

This was Rajadurai’s first attempt in contesting under Federal Party label. He mentions proudly that though his opponents had tagged him as a ‘traitor’ to Batticaloa by contesting in the Federal Party label, as well as supporting atheist policies. Despite these negative propaganda, he was able to defeat two previous MPs – Ahamathulebbe (MP elected in 1947) and Kadramer (MP elected in 1952).

Rajadurai was one of the 10 MPs elected in the Federal Party ticket, from North and East. Other 9 MPs were, S.J.V Chelvanayakam (Kankesanthurai), C. Vanniasingham (Kopay), V.A. Kandiah (Kayts), A. Amirthalingam (Vaddukoddai), V.N. Navaratnam (Chavakachcheri), V.A. Alegacone (Mannar), N.V. Rajavarothayam (Trincomalee), M.S. Kariapper (Kalmunai) and M.M. Mustapha (Pottuvil). Eastern Province returned four Federal Party MPs, among which two were Tamils (Rajavarothayam and Rajadurai) and two were Muslims (Kariapper and Mustapha) from locally influential families. Both these Muslims were kins, Mustapha being the son in law of Kariapper. Both Kariapper and Mustapha subsequently jumped ships to other parties.

Young Rajadurai as the Mayer of Batticaloa, in 1960s

1960 March – double member constituency. This meant, each eligible voter was entitled for two votes, and could cast the vote according to particular choices – either both votes to one specific candidate or split the votes to two specific candidates. Traditionally majority of the voters opt to cast both votes to one specific candidate, along the ethnic lines – either Tamil or Muslim.

Total electorate 37,382; Total votes polled 60,408 (79.8%)

Rajadurai (FP) 28,309

A.H. Macan Markar (Ind) 22,893

Mylvaganam (Ind) 8,242

Vote margin of the winner (1st placing against 2nd placing) 5,416

1960 July – double member constituency

Total electorate 37,382; Total votes polled 57,622 (76.2%)

Rajadurai (FP) 29,853

A.H. Macan Marker (UNP) 22,031

Abdul Latif Sinna Lebbe (FP) 2,484

K.N. Koomaraswamy (TC) 2,300

Vote margin of the winner (1st placing against 2nd placing) 7,822

I’m not quite sure, whether Federal Party nominated two candidates – Tamil and a Muslim for this election. But, this is what de Silva’s A Statistical Survey of Elections to the Legislatures (1979) indicates. This fact deserves confirmation.

1965 – double member constituency

Total electorate 45,078; Total votes polled 67,882 (75.3%)

Rajadurai (FP) 29,023

Abdul Latif Sinna Lebbe (UNP) 12,010

A.H. Macan Marker (Ind) 9,915

J.L. Tissawweerasinghe (TC) 8,107

Ahamed Lebbe (Ind) 4,572

Nadarajah (Ind) 2,298

Vote margin of the winner (1st placing against 2nd placing) 17,013

1970 – double member constituency

Total electorate 51,524; Total votes polled 84,681 (82.2%)

Rajadurai (FP) 27, 661

P.R. Selvanayagam (Ind) 23,082

A.H. Macan Markar (UNP) 17,015

M.A.C.A. Rahuman (SLFP) 14,815

S.J. Arasaratnam (Ind) 624

T Francis Xavier (Ind) 196

Vote margin of the winner (1st placing against 2nd placing) 4,540.

Unusually, in this election, two Tamils got elected, while two Muslims contesting in UNP and SLFP tickets were pushed to 3rd and 4th places. P.R. Selvanayagam, though elected as an Independent, subsequently joined the SLFP.

1977 – double member constituency

Total electorate 63,039; Total votes polled 109,509 (86.9%)

Rajadurai (TULF) 26, 648

A.F. Meera Lebbe (UNP) 25,345

Kasi Anandan (FP) 22,443

Badiuddin Mahmud (SLFP) 21,275

P.R. Selvanayagam (SLFP) 11,797

Vinayagamoorthy (Ind) 383

Vote margin of the winner (1st placing against 2nd placing) 1,302

This 1977 election was the last one, Rajadurai participated as a representative of a Tamil party in Batticaloa constituency. Following the death of S.J.V. Chelvanayakam, the founder of Federal Party, in April 26, 1977, the personal conflict Rajadurai had with Amirthalingam opened with dire consequences to both parties and it split the Eelam Tamil voters into two camps: ‘Those for Amirthalingam against those for Rajadurai’.

I provide excerpts from Rajadurai’s version of the split: “I had won elections since 1956, representing the Batticaloa constituency. Federal Party’s candidates in the Eastern province for the past elections were recommended by me. [Then, in 1977,] the party forced me to contest the Pottuvil constituency. Batticaloa voters rejected this decision. I also rejected it. Then, the party nominated two Tamil candidates… I had been a founder member of the Federal Party since it’s inception. They campaigned against me, the one who introduced the Federal Party to Batticaloa. They should have introduced both candidates for formality sake, and asked the voters to vote for whom you wish to. They didn’t even do this.

In the campaign platforms at Batticaloa, leaders A. Amirthalingam and M. Sivasithamparam spoke not to vote for the rising sun symbol of TULF. Party’s mouthpiece Sutantiran weekly wrote, ‘Not to vote for me’. They sent letters from Jaffna, to Jaffna voters living in Batticaloa, requesting ‘Not to vote for me’. By this deeds, they damaged the trust bond between Batticaloa and Jaffna. But, Batticaloa voters did elect me.”

Rajadurai joined the UNP in March 1979 and became a Cabinet minister. He attempted his luck again in the parliamentary elections of Feb 1989 as a candidate of UNP in Colombo district. And he lost. Simply speaking, Rajadurai couldn’t transfer his Batticaloa magic to Colombo. I’d say, he made a wrong call. In one sense, I feel that this result was also an apt one. Majority of the Sinhalese voters in Colombo, couldn’t accept the veteran Federal Party MP of more than two decades as a UNPer. In their view, Rajadurai was a full-blooded Tamil. Strangely, Amirthalingam himself opted to contest (or should one say, hand-twisted by India’s RAW agency) the Feb 1989 election from the Eastern Province. He also lost!

Rajadurai had written that even within J.R. Jayewardene’s Cabinet, prior to the Rajiv-Jayewardene Accord signed in July 1987, one Sinhalese minister had needled him as ‘loku kotiya’ (Big Tiger) in a Cabinet meeting. What happened was, President Jayewardene had asked the opinion of each Cabinet member ‘what can WE do at the current situation?’ To this, Rajadurai had responded as ‘conduct talks with Prabhakaran’. Following that Sinhalese minister’s (though Rajadurai didn’t identify My guess – maybe Gamini Jayasuriya!) retort, there was harsh exchange of words between him and that Minister. Eventually it was stopped by Jayewardene.

Rajadurai’s agony in 1977

One can easily comprehend the 1987 comment of that Tamil baiting Sinhalese Cabinet minister. He was entitled for it, for his survival as a Sinhalese politician. But, what Eelam Tamils couldn’t easily comprehend was what happened ten years earlier? The attitude (one should also add, arrogance) of the then TULF leader A. Amirthalingam in 1977 to insult Rajadurai, by nominating Kasi Anandan as well in the Federal Party label, to compete with Rajadurai (nominated for TULF) at Batticaloa constituency. Amirthalingam had also chosen a fickle minded Mylvaganam Canagaratnam (1924-1980) as a candidate for Pottuvil constituency in 1977; and after being elected, within few months, Canagaratnam jumped ship to join UNP for a district minister position, only to be shot on January 24, 1978. Had Amirthalingam made a proper leadership decision of directing Kasi Anandan firmly to Pottuvil constituency, he might have avoided the unnecessary conflict with Rajadurai. But this was not to be. Proud Batticaloa Tamils did teach Amirthalingam two lessons: (1) in 1977, by electing Rajadurai to the 1st place, and placing Amirthalingam’s nominee Kasi Anandan to the 3rd position, and (2) defeating him in February 1989.

One redeeming feature in the July 1977 general election result was that only Rajadurai can claim credit for defeating Badiuddin Mahmud (1904-1997), the Rasputinic Muslim minister in Sirimavo Bandaranaike’s Cabinet, who was solely responsible for the ethnic rift between the Tamils and Muslims. Mahmud was placed a poor 4th. I’ll continue this story in Part 2.

Sources

G.P.S. Harischandra de Silva: A Statistical Survey of Elections to the Legislatures of Sri Lanka, 1911-1977, Marga Publications, Colombo, 1979.

Rajadurai Felicitation Volume, Manimekalai Pirasuram, Chennai, not dated (probably 1998?)

Chelliah Rajadurai: Suvadukal (Footprints), Poomagal Pathippagam, Batticaloa, 2008, p. 31-33, 97, 123-126, 130-131.

Ryan B. Socio-cultural regions of Ceylon. Rural Sociology, Mar 1950; 15(1): 1-19.