An autobiographical reflection by Neville Jayaweera

Reviewed by Anura Gunasekera

To an older generation of Sri Lankans the name Neville Jayaweera would need no introduction. Most of those who will ultimately read this book, would do so, not so much for its provocative title, but more because Neville Jayaweera has written it.

Jayaweera belonged to an elite corps of public servants designated “Civil Servants”, who had been recruited through a notoriously difficult open competitive exam. Most of them had First or Second (Upper) degrees, and never numbered more than 150 officers out of a total public service of 250,000 at that time and were the crème de la crème of the University. In truth, they were the silent men behind the scenes who actually ran the country, at least pre-1970. Consequently, they tended to be arrogant and elitist, which made them unpopular with the new breed of post-1956 politicians. However, the majority of them were genuinely “civil”, “highly educated”, “cultured” and totally committed to the core principles of public service. It was an era when the term “Civil Servant” generally signified class and quality, efficiency, and integrity, a world apart from the public service of today.

Until the decline set in post-1970, the CCS epitomized scholarship and intellectual excellence, as illustrated by Jayaweera’s research on the Tamil caste system, carried out whilst meeting the exacting demands of being GA of Jaffna between 1963 and 1965. It is a body of work which further enriches a brilliant tradition of scholarship reaching back to the early nineteenth century, established by the works of Sir William Twynam, George Tourner, R.D. Childers, Rhys Davids, H.W.Codrington, Emerson Tennent and and W.T. Stace, to mention just a few.

The Preface, by Susil Sirivardana, a colleague of Jayaweera’s in the Administrative Service, and the Foreword by Dr. Michael Roberts, provide comprehensive analyses of the book’s contents. Therefore, this review seeks merely to direct the attention of the public to a publication which is a personal memoir, a political analysis of past events and, also, a prediction for the possible direction of future events.

In the context of the strife which has engulfed this country in the last three decades, this book is essential reading. It offers the personal point of view of a man, who was a protagonist in events in the North during a critical stage in the evolution of Sinhala/Tamil relations, events which were accurate precursors of the nightmare to follow 20 years later. It is the recounting of recent Sri Lankan history by a man who was a ringside observer in its unfolding, and one who also made a significant personal contribution to the moulding of epochal events.

All conflicts, whether internecine, international or global, have long histories. Their evolution and development is very visible and, in a final analysis, traceable back to specific origins. Ours was homegrown, internecine and apart from intermittent external influences, particularly in the last three decades, internally generated and fueled by knavish political policy and obduracy and hypocrisy on both sides. I would ask all readers to peruse the Prologue to this book with care and attention. It summarizes, in logical and chronological sequence, why and how the conflict was inevitable.

As much as conflicts have histories of evolution, at any point in their development they are capable of being arrested and the core issues amenable to resolution, given intelligent and pragmatic decision making and integrity of political vision. As Jayaweera traces the history of our conflict, he also clearly highlights the wasted opportunities for resolving it; opportunities frittered away by successive governments and articulators of Tamil aspirations. Prabhakaran, the LTTE and the ensuing carnage was the logical consequence of this intransigence and insincere posturing by both sides.

Many Sri Lankan governments in recent times, particularly the current one, have tried to portray the national conflict as mere terrorism against a democratically elected government. It is a convenient position to hold, in that it provides a justification for the military repression of reasonable dissent, even in the future. The dissent in the North did degenerate in to terrorism, practiced occasionally by the state as well, but it was essentially ethnic in origin. Jayaweera’s book clearly places its ethnic nature and content in proper perspective.

The contribution made to the development of conflict by the obduracy of decades of Sinhala leadership, accepted by some and denied by many, is projected by Jayaweera through many concrete and undeniable examples. However, what is more interesting, though perhaps less commonly discussed by political commentators, is Jayaweera’s analysis of the caste-conscious culture of the North, which posited the hegemony of the Vellala segment in Northern society, which ultimately provoked the violent assertion of underclass discontent and aspirations.

As Susil Sirivardana writes in his preface,” Jayaweera’s work on the Tamil caste system and Hinduism is a monumental piece of research deserving recognition in its own right, as a substantial document that that adds lustre to the old CCS. Jayaweera has brought to the CCS a rare intellectuality and a spiritual depth that kept its reputation for class and quality aflutter, even as its great 150 year old tradition was being laid to rest by the new political culture”.

As Jayaweera expresses unequivocally, for four decades successive Sinhala governments have been negotiating on Tamils’ issues with the wrong Tamils. They spoke to the few highly educated, heavily Anglicized and privileged members of the Tamil “upper crust”, a small minority of Tamil society, perhaps in ignorance of the majority underclass segment which, in reality , was the true face of the problem. As he points out, the political frontline of the Tamil position then consisted of prominent Tamils who had migrated South decades before, and having profited immensely – socially, professionally and financially – by this move, become estranged from the realities of the issues of their less fortunate brethren in the North.

Jayaweera’s position on this issue is reinforced by his experiences in personal negotiations on behalf of this marginalized segment of Northern Tamil society, particularly in the ” Temple Entry issue”, in which the privileged Tamil segment proved as intractable and as incapable of compromise, as successive Sinhala governments have been in the case of larger Tamil issues.

Memoirs of people who have occupied positions of power and influence , especially in the public sector, tend to be, not infrequently, justifications for their own questionable actions, vehicles for self –aggrandizement or a means for the sanctification of the disreputable conduct of their more powerful masters. This is a genre which has produced many tedious and sanitized portrayals of genuinely controversial personalities and tumultuous events. Therefore, It is a relief, and a pleasure, to read an account which is an objective and impartial presentation of events and people, delivered sans offense and with polish. Jayaweera has clearly proved that It is, indeed, possible to present painful truths without calling a spade a shovel.

In the re-telling of his personal experiences as a senior public servant, Jayaweera has woven a rich tapestry of places, people and events, lending perspective and historical and administrative background to an existing national profile. It is also an urgent plea to those who now make decisions, to re-think the ongoing political process, lest a fusion of emerging forces result, “in a threat to the government in Colombo, no less formidable than the threat that the LTTE has posed.” Notwithstanding current government perception, such a future threat may not be amenable to a military solution.

Apart from aspects related to the Sinhala – Tamil issue, Jayaweera opens interesting windows to other, equally significant events in recent Sri Lankan political history. His comments on the background to the emergence of the JVP and the relevance of the Official Languages Act is an aspect either neglected, or ascribed marginal importance by many political commentators, who generally tend to place weightage on the dialectical aspects of the JVP’s Marxian credo. The impact of the uncompromising implementation of the Official Languages Act on Sinhala/Tamil relations – notwithstanding the essential rationality of the Act- needs no elaboration. In this context, “Language as a Tool of Oppression,” is a very apt expression.

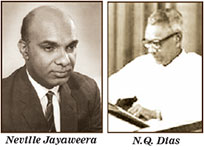

The presentation of “The N.Q.Dias Factor,” [see below for more details] as a pivotal force in moulding both national and foreign policy then, and as a forerunner to the current national political profile and foreign policy direction, is indeed fascinating. It may have been common knowledge in the corridors of power then but perhaps not publicly acknowledged; certainly, it is no longer known or has been forgotten. It was then an administrative milieu in which dedicated and competent bureaucrats advised politicians and, either for good or ill, actually guided the course of government policy. A perfect example is the then Prime Minister Sirima Bandaranaike’s personal and secret authorization- in response to Jayaweera’s proposal- for the reversal of the Sinhala Only policy in the North. This three –language policy, unobtrusively launched and administered in the North by Jayaweera in 1963, was legitimized in 1987 through the 13th Amendment, but only after much blood-letting on both sides.

The publication of this book at this juncture in our political history is most timely as it carries an urgent plea for the Rulers, that we heed the lessons of history and re-envision the course for the future. The tragedy is that history is directional and the consequences of actions both predictable and inevitable. The insensitive implementation of the Sinhala only policy, as analyzed comprehensively by Jayaweera, clearly demonstrates the manner in which a policy designed to redress an imbalance between the English educated North and a similarly privileged Southern minority, and the majority Sinhala only South, did more to marginalize the intended beneficiaries and eventually contributed in a large measure to both the LTTE and the JVP uprisings.

Let me quote what I consider to be Neville’s core message ;

“More than the power it derives from an overwhelming superiority in numbers, what exalts any majority community, and endows it with a true greatness and moral authority, is its willingness to accord to all those other communities who lack the advantage of numbers, a status and dignity equal to its own, and never let them feel marginalized or disadvantaged because they are fewer in number, or because they are different in colour or beliefs.

Unless and until Sri Lanka can produce leaders who can realize that truth, and are willing to act on it, it will continue to be mired in conflict,” ( Page 175)

The reality is both the inability and the reluctance of our leaders to embrace that higher vision. Incontrovertible proof of such intransigence is the implicit support extended by the State to militant Sinhala-Buddhist fronts which are seeking to impose an apartheid between the majority and minority communities in this country, as cruel, senseless and as morally unacceptable as that which existed in South Africa.

In conclusion I quote another passage, a prophecy which warns of tragic consequences;

“……Given the elements that comprise Mahinda Rajapaksa’s consciousness, such a transformation in the southern consciousness is not likely to happen. What is more likely is that Rajapaksa will stoke the southern supremacist consciousness and lead the country in a downward spiral in to a deeper and wider conflict. Rather than promote a transformation of consciousness leading to reconciliation and a new beginning, he might generate circumstances that will suck India in to the conflict again. If that happens, we might witness an outcome which successive governments in Colombo had fought a horrific 30 year war to avoid – namely, the eventual partition of Sri Lanka.” (page 220).

The present regime, having won a military conflict internally, is now besieged by forces which have internationalized the many immoral and amoral aspects of its post-victory conduct and style of governance. It is now fighting a war which it can never win militarily. May I, on my own, add that those who have their backs to the wall , are unable to read the writing on the wall.

For those serious readers who are genuinely interested in the evolution of the current Sri Lankan political profile, this book offers valuable substance. It is informative, educational and amusing, a combination of features only a clever writer can harness in their proper proportions. They are the views of a man who witnessed events from inside out, as against the professional political analyst who sees them from outside in. His positions are also supported by diligent, scholarly research and sources which are clearly both reliable and authoritative.

At a paltry Rs. 500/- per copy, the book is great value for money and is obtainable at “Ravaya”, 83, Piliyandala Rd., Maharagama ( Tel; 011-2896330/112-851672/73). Victor Ivan has provided a fine service to the discerning reading public of this country.

—————-

Into the turbulence of Jaffna

(a chapter extracted from the author’s unpublished memoirs, titled “Dilemmas”)

The story of my immersion in the turbulence of Jaffna actually begins in Badulla, in July 1963. In April of that year I had completed three gruelling years as the General Manager of the Gal Oya Dev.Board and had asked for a posting where I could catch my breath, so to say, and recuperate. The Sec. to the Treasury obliged by sending me as Government Agent (G.A.) of Badulla, where I had served as Assistant (AGA) few years earlier and where Trixie my wife, and I, quickly settled down to a more leisurely and spacious life, working amidst the welcoming and verdant villages of the Uva province.

Prime Minster Mrs Bandaranaike for tea

Our three months of quietude and recuperation ended abruptly one evening in July 1963. The Prime Minister, Mrs Sirima Bandaranaike (Mrs B) who was addressing a political meeting nearby, dropped in at the Residency (as the official residence of a GA was called in those days) for a short rest and some tea. That was my first face-to-face encounter with the redoubtable lady. I must say that contrary to the image of arrogance often associated with her, at least that evening, she was a model of grace, charm and humility. Over tea, quite casually, she turned to my wife and said,

“Mrs Jayaweera, I know that you have hardly settled down in Badulla after the hard time you both had in Gal Oya, so I don’t know how you will take this suggestion. My government is having a serious problem coming up in Jaffna, where we have to implement the Sinhala Only Act in all government departments from October this year. But the Federal Party is resisting it strongly and giving us a lot of problems. They are now planning to launch a big campaign in October, called the Secessionist Movement, to coincide with the implementation of the Sinhala only policy. I understand that your husband did a very good job at Gal Oya. So we are hoping that he will do a similar job for us in Jaffna. Would you object if I transfer him now to Jaffna?”

My wife was aghast and looked at me not knowing what to say. Mrs B continued, “I know that your husband, being a disciplined public servant will go wherever the government wants him, but I won’t ask him unless you agree first, because I know it is the wife who suffers when the husband is transferred from place to place so quickly”.

Mrs B’s concern for my wife’s feelings was most disarming, but needless to say, the ensuing conversation was short and to the point and within a week I had received orders to proceed to Jaffna as GA, by the end of August of that year.

The N.Q. Dias – The Tsar!

However, before I could assume duties in my new post, Mr N.Q.Dias, the Permanent Secy, Defence and External Affairs, telephoned me one day and asked me to have lunch with him at the his favourite luncheon haunt, the terrace of the Gall Face Hotel (GFH ). At that time N.Q.Dias was not merely the Perm. Sec. Defence and External affairs, but the most powerful public servant around, and because of his influence over Mrs Bandaranaike, feared and respected even by Cabinet Ministers, and referred to publicly as The Tsar. It was therefore with some apprehension that I joined him at lunch that day.

I had met N.Q.Dias an year earlier when he visited me in Gal Oya along with his Assistant Secretary, Mr Stanley Jayaweera (my brother) to inquire whether the Gal Oya Board could turn out boats that the navy could use for anti-smuggling work. Apart from that encounter, which was brief, I had no knowledge of this man, except by reputation.

Over a gourmet meal, Dias told me that that it was he who had suggested to the PM to appoint me as GA of Jaffna, and that he had to brush aside a strong protest from the Home Ministry that I was too junior for the job. Which indeed I was, for I was only 33 then!! He said that he had asked for me because he had been impressed at the way I had managed the Gal Oya Board, with its notoriously militant trade union workforce of over 14,000 men, and felt that I was the man to handle the turbulence in Jaffna.

Dias then went on to spell out a remarkable vision of events he said are bound to unfold in the not too distant future. He had a deep conviction that within the next twenty five years or so, the Tamil protest will develop into an armed rebellion and that the Government must prepare from now (i.e.1963) to meet that outcome. He said that my principal role as the GA of Jaffna, while enforcing the Sinhala Only Act, will be to help him develop counter measures for dealing with the anticipated uprising, and then proceeded to unfold to me his grand strategy for containing it.

The grand strategy

Even as Dias was unfolding his grand strategy it struck me that he seemed to have taken a leaf from Germany’s famous Schlieffen Plan of 1905 to encircle Paris in the event of war. The centrepiece of Dias’s strategy to contain a future Tamil revolt was to be the establishment of a chain of military camps to encircle the Northern Province, all the way from Arippu, Maricchikatti, Pallai, and Thalvapadu in the Mannar District, through Pooneryn, Karainagar, Palaly, Point Pedro and Elephant Pass in the Jaffna District, and on to Mullaitivu in the Vavuniya District and Trincomalee in the East. He said that there were already two military camps of platoon strength in Pallai in Mannar and in Palaly in Jaffna and a rudimentary naval presence in Karainagar, but that he wanted to upgrade them.

He said that he was aware that any attempt by the government to establish permanent military camps in the Northern Province was bound to trigger massive protests from Tamil leaders. However, he seemed to have thought out a masterly subterfuge to disguise their true intent. He said that he was planning to make a huge public issue of two national problems, namely, illicit immigration from India into Sri Lanka, and smuggling from Sri Lanka into India, and argue that in order to choke off this two way flow, which was obviously detrimental to Sri Lanka’s national interest, his proposed military camps were absolutely necessary. The whole military operation was therefore to be disguised as if it was a measure to cope with two major national problems -illicit immigration and smuggling – and without seeming grossly unpatriotic, no one could raise a dissenting voice against it.

He went on to say that he was planning to set up a task force called TAFFI (Taskforce Anti Illicit Immigration) under the command of Lt. Col. Sepala Attygalle (later to be Gen Attygalle, Commander of the Army), ostensibly to contain illicit immigration and smuggling, but in reality designed to encircle the North militarily. He said that he will instruct Attygalle to work in close liaison with me and provide a military back-up for my administration, to facilitate which, he said he had already ordered that an SSB radio link to be installed in my private office in Jaffna. He also said that he will also be placing 3 other hand picked CCS men as GAs to the three adjacent districts, as the other actors in his grand design – I.O.K.G.Fernando to Mannar, R.M.B.Senanayake to Vavuniya and M.B.Senanayake (or Elkaduwa – am not sure ) to Trincomalee.

N.Q. Dias’s remarkable prescience encompassed other prophetic insights as well. He also envisaged that some day in the future India was bound to stoke a Tamil uprising in Sri Lanka and that Tamil Nadu will be a source of illicit arms for the rebellion. To prepare for such an outcome he said it was necessary to develop a completely new naval strategy for Sri Lanka and proceeded to ridicule the policy current then, of building a navy comprising mine sweepers and frigates such as Vijaya and Gajabahu, which he said were only of ceremonial and prestige value, but of no use for interdicting gun-running across the Palk Straits. Instead, he advocated building a fleet of small, fast boats and to this end had even contacted the US Ambassador Cecil Lyon to see whether the US government might consider gifting some old PT boats to Sri Lanka, sans the torpedo tubes, as a part of their foreign aid package!! That was at the height of the Vietnam War and PT boats were very much in the news then. I recall that when Cecil Lyon made his first official visit to Jaffna some time later, he confirmed this to me. Dias went on to say that he would submit a cabinet paper proposing that Vijaya and Gajabahu be de-commissioned and replaced with small fast boats. At that time the Dvora class FAC’s of today were not heard of, but I recall that the Sri Lankan navy did buy a hydro-foil fast boat in the mid 1960s as an experiment. I did not follow up on Sri Lanka’s naval development after I left Jaffna.

As for my role as the GA of Jaffna, Dias said that while enabling the construction of the proposed military camps girdling the Northern Province, I should be unrelenting towards Tamil demands, and wherever possible, force confrontations with them and establish the government’s undisputed ascendancy. He emphasized that the Sinhala Only Act must be enforced at any cost, and was of the view that the government had failed so far to deal with the Tamils forcefully enough and saw me as the answer to the problem! Obviously, N.Q.Dias was seeing me as an administrative Rottweiler to be let lose within the sheep pen of protesting Tamil satygrahis!

N.Q. Dias – the paradox and the prophet

A short note on N.Q. Dias (NQ as he was referred to by colleagues) is apposite here. Actually, NQ was more than merely a public servant or a military strategist. He was an iconic phenomenon, surfing the tidal wave of Sinhala- Buddhist nationalism that had erupted out of the abyss of Sri Lanka’s history. However, to understand him fully we have to grasp two totally contradictory personalities in which he was framed.

Within one frame, along with L.H.Mettananda, F.R.Jayasuriya, K.M.P.Rajaratna, and Bhikku Henpitagedera Gnanasiha, though only a public servant, NQ marched in the vanguard of the 1956 Sinhala-Buddhist renaissance and was the archetypal ultra-nationalist. When Mr S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike swept to power in May 1956 he offered NQ the choice of any public office he desired, but rather than choose to be the Secretary to the Treasury which was the highest office a Civil Servant could aspire to, he chose the comparatively lowly post of Director Cultural Affairs so as to be able to consolidate the cultural gains of Bandaranaike’s great victory. He was also the first public servant to swap western attire for the national dress. N.Q. was also an implacable xenophobic, considering Indians, the Tamil people, the Roman Catholic Church and western culture to be abominations. Not least, he was utterly paranoid about India. Having read and internalised the Panikkar Doctrine which postulated the inevitability of Indian hegemony in the Indian Ocean, he believed that India had sinister designs on Sri Lanka, if not to take the island over completely, at least to keep it permanently disabled and dependent on India.

Within the opposite frame however, N.Q.Dias was also the ultimate colonial CCS stereotype and pukka sahib. He was not fluent in Sinhala, was aloof and arrogant, was wealthy in his own right, played an impressive singles at tennis at one of Colombo’s elite clubs, and lunched regularly on the GFH terrace to the accompaniment of his favoured aperitif, gin and tonic. Although he wore the national dress, he certainly wasn’t the people’s public servant stereotype! To the contrary, everything about him, except his xenophobia, testified to a man from the decadent past, which the 1956 revolution claimed to have swept away. Not least, he never jettisoned his westernised names- Neil Quintus Dias, even as a concession to his extreme nationalist ideology. Nevertheless, his children were not named Dias and were given the Sinhala surname Dayasri. However, though most of his colleagues disliked him for his stand-offishness, they conceded that he was an honourable man, brilliant, disciplined, incorruptible and always observing the work ethic and traditions of the old Civil Service. As Head of the Foreign Office, he also preserved the dignity of the fledgling Ceylon Foreign Service, and kept the diplomatic corps posted to Colombo strictly on the leash, not allowing them to rampage through the country as they did in later years. When the UNP formed a government in 1965 he was forced into retirement, but emerged again in 1970 when Mrs Bandaranaike returned to power and was sent as High Commissioner to New Delhi. However, as to how his life unravelled as our High Commissioner to New Delhi, I am unable to discuss here.

In the course of that luncheon afternoon at the GFH in July 1963, N.Q.Dias also shared with me the story of how he metamorphosed from the stereotype CCS pukka sahib he once was, into the ultra nationalist and xenophobic he was now proud to be. It is a deeply fascinating and extraordinary human story, both spell binding and incredible! Unfortunately, to chronicle that drama will require a whole new chapter but this is not the place for such a digression. The telling of that story must wait awhile.

N.Q.Dias’s multidimensional strategic vision of an armed Tamil uprising, India’s intervention on the side of the Tamil cause, and gun-running from Tamil Nadu, began to unravel exactly as he had foreseen. To that extent Dias was a political prophet as well as a military strategist bordering on genius. His grand design for strangling a future Tamil revolt by girdling the North with a chain of military enclaves was as audacious as it was brilliant. Proof of Dias’s brilliance was that, when within two decades events began to unfold as he had prophesied, it was this iron pincer around Jaffna’s neck that served as the Sri Lankan Army’s bulwark against the Tamil militant groups. Had it not been for this chain of garrisons, the government would not have had platforms from which to mount counter strikes against the armed rebellions that have confronted the country since the 1980s.

It will not be an exaggeration to say of N.Q.Dias that he was Sri Lanka’s Clausewitz.

I did not share N.Q.Dias’s ideology or world view, except very briefly, may be for a few months, when I came under his mesmeric influence. However, I concede that he was a man of extraordinary courage, totally dedicated to his convictions, principled, unafraid and incorruptible.

The Dias paradigm

None can deny that within his paradigm, Dias’s grand strategy was brilliant, audacious and prophetic. However, the operative concept here is “within his paradigm”. Paradigms are not self legitimising, especially those that concern socio-political problems. While paradigms in the physical sciences have to be tested against empirical criteria, those that pertain to politics and the social sciences have to be tested against universally held values, within which they must stand up to moral scrutiny. We must ask in respect of them, whether they uphold fundamental rights, equality, liberty and justice for all, and promote harmony and peace among all communities, regardless of ethnic or religious divisions. In that context, there are several questions to ponder about the adequacy of the Dias paradigm and I would like to turn my attention to them later on in this chapter.

However, for the moment let me turn to the dramatic events that engulfed me no sooner I had taken over as Jaffna’s new GA.

————-

Into the turbulence of Jaffna

A Sinhala conquistador

I must confess, that being chosen as the pivot of N. Q. Dias’s master plan to enforce the Official Language Act throughout Jaffna, to encircle the North with military camps and bring the Tamils to heel, released in me a surge of gung-ho energy, and it was in a spirit of a Sinhala Conquistador, resolved to plant the Lion Flag and Sinhala supremacy among a troublesome Tamil people, that I sallied forth. Except that, for a coat of shining armour I had only a thick coat of juvenile hubris and for my steed a clapped out motor car. Forty years on, I cringe in shame and disbelief when I recall that a Sinhala Sunday paper of that time, referring to my posting to Jaffna, called me the new Sapumal Kumaraya. I have no plea to offer in mitigation except the vacuous ego’s eternal vulnerability to delusions of grandeur.

So it was that one evening in late Aug. 1963, Trixie and I (our daughter Mano was not born yet) were driving into Jaffna, having relinquished duties as the GA of Badulla the previous day. As we drove past Paranthan I remarked to my wife that we seemed to be coming into a wholly different country. The lush thick vegetation of the South had given way to low, parched and scattered scrub. The undulating green hills and valleys carpeted with tea bushes and terraced paddy fields that had been our universe in Uva, had yielded to rolling sand dunes, sprouting spindly Palmyra palms, looking like giant tooth picks stuck in the sand. It was like a lunar landscape, barren and sparse, and from both sides of the Elephant Pass causeway, salt crystals reflected the setting sun like myriads of glass beads.

Dusk was falling as we pulled up under the porch of the Jaffna Residency and our immediate reaction was one of extreme depression. The 100 years old mansion, built as the private residence of Jaffna’s first GA, Sir Percival Acland Dyke in the 1860s, and left unoccupied for some time now, my immediate predecessor V.P Vittachi having left a few months earlier, looked vast, gaunt and ghostly. Its ancient walls, scarred by peeling plaster and held together by green ivy and lichen, were oozing with rising damp. Giant louvered doors, that had not seen a coat of paint in over 50 years, creaked on rusty hinges. Cobwebs trailed from the ceiling like lace curtains, and the wind blowing like a torrent outside, served to emphasise the gloom. When my wife turned on the tap to fill the kettle so that we may have a cup of tea, some foul brown liquid gushed out. Every prospect seemed utterly forbidding.!

A wall of hostility

Uncharacteristically for an incoming GA, barring Ivan Samarawickrema the AGA, a Sinhala officer, not a single local official was on hand to greet us. I did not fail to notice the absence of the Head Quarters DRO ( Divisional Revenue Officer ) and of the Office Assistant, both Tamils officers, whose presence to welcome an incoming GA was a long established tradition in Provincial Administration and almost mandatory. Their absence that evening, even though the Home Ministry had kept them informed of my imminent arrival, was a clear signal to me that an organised boycott was on the agenda.

Things deteriorated sharply the very first morning I went to my office. Our Alsatian dog Shaami had been used to trailing me wherever I went. My office being only a few yards away from the Residency, Shaami walked beside me to my new place of work that first morning and curled up by my chair . It was a very friendly dog, seeking only to be petted and patted by strangers, but on this occasion, totally to my consternation , sprang at the very first local who came to see me, and shredded his 22New Sinhala GA sets his dog on Tamils”. I sensed a wall of hostility rising before me.

As the days passed, everything around us, even the very soil, seemed to shout out the unfriendliness of the Tamil people and my wife and I were oppressed by the thought that we were total aliens here. Wherever we went, at the fish market, or at the grocers, or even at the cinema, we were greeted by a wall of silence and the whole ambience reeked of suspicion and mistrust. It was quite eerie and chilling. It used to be the convention in my time, for senior officials of the district to call on a new GA and his wife when they first moved in, but in this instance not a single local official, bar Ivan Samarawickrema the AGA, and two burgher officials, the Suptd of Police Jack van Sanden and the Asst. Com. of Excise, John Martin, called on us. The wall of hostility was palpable and impregnable. On the other hand, my predecessor V.P. Vittachi did not have to run this gauntlet. The reason was plain to see. The word had got around that I had been handpicked for Jaffna by the Prime Minister and her Perm. Sec. Mr N.Q.Dias, to do a hatchet job on the Tamils, which of course was pretty close to the truth!

The Yogi or the Commissar

Already, within the first few days, even before I had gone into any real confrontation with the Tamil people, I had begun seriously to rethink my role as a GA consenting to work within the vision unfolded to me by N.Q.Dias. As the days passed, my failure to question the morality of that assignment initially, filled me with a deepening disquiet, and in no time the disquiet turned to anguish. I began to understand then, exactly what Leonard Woolf meant when he said that, as the AGA of Hambantota, way back in 1907, he felt as if he was a ruler and an imperialist, roles he said he loathed.

The religious beliefs I held at that time also sharpened my perplexity. At that time I was a totally committed Buddhist, and since my youth had been an ardent student of Abhihdhamma. I understood the Thathagatha’s central doctrines, especially the concept of anatta, to mean that all identities, whether personal, or familial, or ethnic, or national, i.e. basically the “i” –“my” concept, are derived from avijja, or ignorance of things as they are, the yatharthaya, and are illusions, or maya. Logically, it followed that all ethnic and national distinctions were false and illusory and that conflict, whether between individuals, or between races, or between nations, arose because of this fundamental cognitive or spiritual error. Therefore, it seemed to me that within the Buddha’s epistemology, insofar as they all postulated attachment to error and illusions, there was no room for ethnic distinctions, for nationalism or even for patriotism. It seemed to me therefore that the thinking that drove the Sinhala Only policy was spiritually flawed and untenable within the framework of the belief system that Dias and I shared at that time.

The problems that I was facing were therefore not merely administrative in character but were deeply rooted in consciousness.

I was caught at the intersection of two contradictory loyalties that kept tightening like a vice, by the day. On one hand, as a public servant, I had to be loyal to the government and its policies which I was bound to implement regardless of my perception of their moral validity. On the other hand, as a human being endowed with an innate sense of justice and fair play, I felt that I should obey the demands of a loyalty that transcended the mundane obligation to conform to government policies. I suppose that at some point, whoever is invested with power, and is also endowed with a conscience, is called upon to resolve the dilemma between horizontal and vertical loyalties, between the expedient and the moral. To yield unquestioningly to the horizontal or the expedient is the populist way, the way to win the approval of the world and to be applauded by it and to partake of the gravy train. On the other hand, yielding to the vertical or the moral, is the unpopular way, guaranteed to incur the world’s wrath and ridicule, and to be condemned by those in authority.

Worse, I have found in experience, that some, having blatantly chosen the path of expediency and opportunism over principle and integrity, try to salve their conscience by adducing superficial theological and philosophical jargon in support of their palpably dishonest choices. .

At the risk of being overly personal, I want to digress here, and confess that throughout my career, and indeed throughout my life, this contradiction has haunted me. While the great “Other”, or the spiritual reality, kept stalking my mundane preoccupations,

I fled Him, down the nights and down the days;

I fled Him, down the arches of the years;

I fled Him, down the labyrinthine ways of my own mind; and in the mist of tears I hid from Him

Francis Thompson ( the Hound of Heaven)

That is not to say that I refused to meet the world’s demands upon my career, but that while fulfilling them with utmost intensity, I felt constantly overshadowed by a sense of the unreality of what I was doing. The world saw only the mask, the disciplined and ruthless administrator who produced results regardless, but it had no sense of the inner torment that that mask concealed. The conflict that began stirring within me as I started to address my responsibilities as the GA of Jaffna was just one instance of that perennial predicament.

In a classic essay written in 1945, Arthur Koestler the great novelist of the Cold War era, had conceptualised that predicament as the struggle between two irreconcilable paradigms, between the Yogi and the Commissar. The Commissar, representing the outer or the mundane, sought to change the world by force, through political manipulation and through blood and iron, whereas the Yogi, the inner or the spiritual presence, insisted that the Commissar’s way will never work and that the only way forward was through inner spirituality.

The Commissar is ego or atta, the fallen man, the earthly embodiment of evil, and the product of avijja or ignorance, whereas the Yogi is non-ego or anatta, the resurrected man, the new creation, the earthly embodiment of the divine and the product of vijja or illumination.

In his poem “Paracelsus”, Robert Browning, summed up the Yogi’s paradigm, in the following words,

TRUTH is within ourselves; it takes no rise

From outward things, whatever you may believe.

There is an inmost centre in us all,

Where truth abides in fullness; but around,

Wall upon wall, the gross flesh hems it in.

Throughout my career the Commissar was seemingly in total command, while unseen by the world, but insistently from within, the Yogi was pleading to be heard. It was only much later in my career that I finally took the great leap into the void and allowed the Yogi his voice.

To get back to the Jaffna narrative, amidst great inner pain, I resolved the dilemma at least temporarily, by gradually dropping the Commissar mask and resuming my role as a true public servant. However, resuming the role as a public servant demanded from me conduct that was unambiguously honest, just, and fair, by the people whose interests I was supposed to serve. It was not at all an easy task, as the unfolding events proved.

First confrontation with the MPs

It seemed as if nothing could dispel the image the Tamil leaders had of me that I was N.Q.Dias’s Rottweiler! With rumours about my supposedly tyrannical style bubbling up all around me, things could only get worse, and they did.

Two weeks into my new job, I called a conference of the District Coordinating Committee (DCC), a committee of all local Heads of Departments, numbering about 35, along with all the eleven local Members of Parliament (MPs), just to get acquainted with them.

Even as the clock ticked away towards 9.30 a.m. which was the time fixed for the conference, the GA’s large conference room began to fill up. However, I sensed something in the air that morning, something eerie, as if everybody had an inkling of something about to happen. Almost on cue, at 09.30, led by the redoubtable S.J.V Chelvanayagam, all eleven MPs of the district, all of them from the Federal Party, trooped in silently, in single file, and took their seats. There was no banter, no idle talk, as there normally is when such a conference opens. Everyone seemed to sit on the edge of their seats and it was if I could slice through the tension with a knife!

Speaking in English I opened the conference by introducing myself. I could not proceed any further before Dr. E. M. V. Naganathan, in lay life a fine gentleman, but as an MP notoriously volatile, stood up and addressing me in Tamil said,

“Mr GA, you are here as a ruler and as an oppressor. We don’t want you here and you can go back to wherever you came from. If you proceed with this conference any further I shall brain you with this paper weight”

and so saying actually picked up a glass paper weight from the conference table and raised his hand as if to throw the missile at me. Pandemonium ensued. While I remained calm in my chair, officials around me sprang at Naganathan and retrieving the paperweight from him, pinned him down to his chair. Ivan Samarawickrema, my AGA, , quietened things down and proffering sound advice to the MPS helped to restore normalcy. However, it was clear that I could not proceed with the meeting and had no alternative to adjourning it. The Superintendent of Police, Jack van Sanden, who was a participant at the conference, wanted to prosecute the MP for attempted assault but I insisted that there should be no prosecution.

Three daunting options

It was becoming increasingly clear to me that the MPs, and the people of Jaffna, had made up their minds that I was an agent of an alien power. It also became quite obvious to me that if I was to do my job, meeting the demands of justice and fairplay, I had first to dissipate those feelings of hostility. The task was a daunting one, requiring diplomatic skills, understanding, patience and wisdom, such as in my short career of eight years, I had not been called upon to deploy. It was like riding a bicycle on the high wire, while twirling a parasol over my head!

I had three options before me. I could resign from the Service, but that I could not do because I had a young family and needed the job. Or, I could try to suppress the upsurge of my inner discontent and somehow carry on, pretending that it was not there. That alternative was too distasteful and impractical and I could not have lived through it. Or, I could resort to the daunting option of explaining to the Prime Minister the impossibility of the task she had given me and try to persuade her to rethink her government’s policy in Jaffna. I chose the last option, however unpromising the prospect.

I mused that since Mrs B had come all the way to Badulla to recruit me for this job, bypassing the Sec. to the Treasury and the Home Ministry, thereby violating protocol, I might bypass protocol myself and access her directly, as indeed she had asked me to, should I ever be in trouble. Here indeed was trouble aplenty!!

Accordingly, one night I telephoned the Prime Minister directly to Temple Trees and explaining my predicament very briefly, asked to see her, not at an official meeting as such, but unofficially, personally and confidentially if possible, because what I had to share with her I preferred to keep off the record. Mrs Bandaranaike seemed quite understanding and sympathetic and even deeply maternal, and agreed to see me the following day itself, but late in the evening.

Late the following evening, on arrival at Temple Trees, I found to my absolute dismay and horror that the PM had also invited to the discussion her Perm.Sec, N.Q. Dias, my sinister sponsor and handler!! The imminent encounter with the mighty N.Q. in the presence of the Prime Minister was bound to be a horribly unequal contest. To borrow some naval jargon it was like a sloop taking on the Flagship of the Fleet ( NQ) head on, with the First Lord of the Admiralty ( Mrs B ) watching!! I feared he would simply blow me out of the water. Oh dear!! I thought to myself! How would i emerge from this encounter, if I ever would!! Here I was, confronting the two most powerful individuals in Sri Lanka at that time, with nothing to commend my audacity but a deep conviction that what was unfolding in Jaffna was unjust. NQ had 30 years service under his belt, was the most powerful public servant around at that time, and feared, whereas I had only 8 years of service to stand on, and in his eyes, a mere junior, a upstart, and above all, his protégé. This was hardly a level playing field!

Quite literally, I hoped that, in response to my pathetic situation, some lightning bolt from heaven would strike us all down and finish us off , the Big Bad Wolf and all! But it was not t be. Such stuff are only of fairy tales.

What was about to unravel would prove catalytic, not only for my administration as GA of Jaffna, but for the future of the Official Language Act in Jaffna as well, and not least, for my own career!

Let me relate how the evening’s discussion unravelled

————-

by Neville, Jayaweera, ‘The Island,’ October 19, 2008

Into the turbulence of Jaffna- Part 3

(a chapter extracted from the author’s unpublished memoirs, titled “Dilemmas”)

As the curtain went up on the evening’s drama, I felt like little David facing up, not to one Goliath, but to two, I mean figuratively of course!! However, it was not the formidable Mrs. Bandaranaike who filled me with trepidation but N. Q. Dias. I have never seen N.Q. abrasive in speech or manner, being always soft and gentle in tone, but that silken exterior concealed a core of steel and resolve.

Contrary to my expectations that evening, the whole ambience was delightfully homely. The Prime Minister was meeting us not at a conference table but in the ample lounge of Temple Trees, comfortably sunk in deeply upholstered settees, and sipping orange juice to the sound of clinking ice cubes. There were no secretaries at hand and no one taking notes. She was dressed informally and was without her ubiquitous handbag, which like a sovereign’s sceptre used to announce her imperious presence. With a string of warm personal inquiries about my wife and my family, made in her familiar gravelly voice, Mrs. Bandaranaike drained whatever tension there was in the air and transformed the evening’s proceedings into an informal chat.

After the conversation had meandered aimlessly for about 30 minutes, Mrs. Bandaranaike turned to me quite casually, and as if it was an afterthought and said, “So Mr. Jayaweera, what is this big problem you have in Jaffna that you asked to see me”? That was the opening I was waiting for.

First I apologised to the PM for my presumption in not coming through the proper channels, but she quickly put my mind at rest by saying, “No, that’s alright by me, because you are seeing me unofficially. However, I hope that Felix (meaning Felix Dias Bandaranaike Minister of Finance and political head of the Public Service at the Treasury) and the Home Ministry will not give you trouble.”

I then set out for the PM three problems I wanted to discuss with her informally. My first problem concerned the practicalities of implementing the Official Languages Act, (OL Act.) commencing the first of October, for which I had been specially posted to Jaffna. (the Official Languages Department functioned directly under the Prime Minister) My second problem concerned the wisdom and morality of enforcing the OL Act in Jaffna and my third problem concerned a difference of opinion I had with Mr. Dias as to how I should handle protests from the Tamil populace.

First, I explained to the PM that the implementation of the OL Act in Jaffna from the 1st of October 1963, was a practical impossibility. Of the 50 Sinhala clerical staff who had been posted to Jaffna for implementing the Act, 48 had either submitted medical certificates or had seen their MPs and had their transfer orders cancelled. Ivan Samarawickrema, my AGA, and I, and two Sinhala clerks were the only Sinhala staff throughout the District and we had one Sinhala type writer between us. To make matters worse, Samarawickrema had received transfer orders to proceed as GA of Polonnaruwa.

Secondly, I questioned the wisdom and morality of trying to enforce the OL Act in the Jaffna District. I made it clear that I was not questioning the wisdom of the Act as national policy, for to do so would have been presumptuous, but I was questioning the wisdom and morality of enforcing it in the Jaffna District, which was a question within my remit. I said that under the provisions of the Act, all receipts issued by the government for payments, all invoices, all registrations of births, marriages and deaths and all correspondence with members of the Tamil public, and the language of the courts and court records, should be in Sinhala. Apart from the practical impossibility of conforming to these requirements, I said that it was grossly unfair by the people and any attempt to force the issue will only aggravate hatred and conflict. I turned to N. Q. Dias and somewhat impudently asked,

“Sir, how would you like it to have your children’s marriage certificates issued in Tamil, or your grand children’s birth certificates issued in Tamil or your own death certificate issue to your next of kin in Tamil?” N.Q. made no response but kept fidgeting with his wristwatch.

I said that as a practical first step towards reconciliation the government must refrain from forcing the OL Act on the Tamils at least within the Jaffna District. Given that for practical reasons the Act could not be implemented in Jaffna in any case, it would be more prudent to abrogate it rather than pretend to enforce it and aggravate conflict. I said that at the same time the government must allow the GA of Jaffna to implement the Reasonable Use of Tamil Act within his district, at least in the spirit if not in the letter. This Act, conceived by her dead husband as a partial accommodation to the Tamils, had not been gazetted yet, though passed in Parliament.

Thirdly, I raised the question of how to handle the impending mass protest which the Tamil leaders were mobilising as a launching pad for the Secessionist Campaign, which was due to erupt two weeks from that day. It was to deal with this campaign that the Prime Minister had hand-picked me for Jaffna. I referred to two of her previous handpicked nominees who had been sent to Jaffna to resolve the conflict, Nissanka Wijeratne (GA for a few months in 1961) and the military co-ordinator Brig. Richard Udugama ( 1961/62) who succeeded him, and suggested an approach fundamentally different from theirs. I said that rather than be confrontational I would opt for dialogue and conciliation and suggested a slackening of the intransigence with which the government had confronted the satygrahis in 1961.

In conclusion, I said “Madame, trust me, and let me handle it my way. I promise you that before I complete my tenure in Jaffna I will create a climate there within which the government and the Tamil parties will be able to resume a dialogue. I cannot make political decisions. That is something that only the government can do, but I will give you an environment in Jaffna, in which the government leaders and Tamil leaders together can make sane decisions”

I wound up my presentation to the Prime Minister by saying that given all the facts that I had placed before her, unless there was some let up on the part of the government, it will be impossible for me to function effectively as GA of Jaffna, and that I will have to ask her very respectfully, to relieve me of my duties and post me elsewhere.

The Prime Minister’s response

The Prime Minister listened to me patiently as I talked for about thirty minutes, but I must confess, she was somewhat taken aback at the depth of my conviction and the passion with which I articulated it. However, while she kept plying me with many questions, I seemed to have plucked a sympathetic cord within her.

After I had finished speaking, an ominous silence enveloped us. No one spoke and I started buckling my brief case, expecting to be told that I should go back to Jaffna and clear out my desk.

After about three minutes, to my absolute astonishment, the Prime Minister turned to me and said that she quite understood my predicament and sympathised with me. She went on to say that as an experiment, and as long as the experiment was limited to the Jaffna District and is not publicised, she would go along with my proposals, but that there will be no official change in government policy, and neither will there be any written confirmation of what was said at this discussion. It was many years later, after I had ventured into the murky world of double-talking diplomacy, that I learnt that there is a thing called “complete deniability”, which is to say that two parties can agree upon some matter secretly, but that if necessary both sides are free to deny that a meeting ever took place, or that an agreement was ever reached. This was my first exposure to that world of double-talk.

The Prime Minister said that she would watch how the experiment worked and if everything went smoothly she will bring the Cabinet into the picture.

Turning to NQ she said, “We hand- picked Mr. Jayaweera for this Jaffna job, so why don’t we let him handle it his way”? Dias was visibly displeased but the PM remained unmoved.

Let there be no confusion. The Prime Minister’s nod to me that day did not signify a turnaround in national policy, either on the language issue, or on the general attitude towards Tamil grievances. Nor did it mean that her basic thinking on the broad question of the rights of minorities had undergone a dramatic transformation. It certainly was not a decision given after consulting the Cabinet, or with its knowledge, or after a discussion within her Party. I had no illusions that it was none of these. My interpretation of the Prime Minister’s ruling given that day was that it was purely an ad hoc administrative dispensation, handed down to me unofficially for solving what she saw as a local problem and in no way did it signal an ideological shift.

I also felt that underlying Mrs. Bandaranaike’s reaction to my presentation was an implicit trust in my bona fides. While she must have been quite embarrassed by my negative reaction to her government’s policies, which she had handpicked me to implement, I believe she was also convinced that I was motivated by a genuine concern for the long term interests of her government and not least, of the country.

Let it not be forgotten that while being allegedly capable of vengefulness and pettiness, Mrs. Sirima Bandaranaike could also be deeply considerate, overwhelmingly compassionate and pragmatic. Up to that moment I had seen nothing of the former characteristics in her, but an abundance of the latter.

An experiment in alternative governance

Prime Minister Mrs. Bandaranaike’s extraordinary magnanimity that evening opened the door for me to launch within the Jaffna district an experiment in governance with justice and righteousness towards all. Without any official pronouncement to that effect, I allowed the OL Act, which I was expected to enforce rigorously within my district to lapse, and instead proceeded to implement the Reasonable Use of Tamil Act.

What this meant in practice was that the policy handed down from Colombo that birth, marriage and death certificates should be written only in Sinhala and likewise all receipts and invoices, was not implemented. Instead, these documents could now be issued in any of the three languages, as requested by the recipient party. Letters written to members of the pubic by all government departments within the district continued to go out as before in Tamil or English, and the courts continued to function as before without any change in language. In the day to day administration of Jaffna it was as if the OL Act had never been enacted.

The precedent I established in Jaffna over the three years of my tenure was virtually set in concrete, in that, none of the GAs who followed me, veered from the pattern I set in respect of the OL Act.

I must emphasise that there was no stealth or duplicity on my part. Despite the commitment to secrecy that evening at Temple Trees, within a few weeks the Cabinet and the government as a whole became fully aware of what I was doing, but preferred to turn a blind eye and remain complicit. In effect therefore, though the OL Act remained on the statute book till it was effectively abrogated with the 13th Amendment in 1987, it was never effective or enforced in Jaffna.

Revisiting Dias the strategist

Before I conclude this section I would like to revisit the Dias paradigm, which earlier on in this chapter I said I will revert to later. I did not open it up for discussion that evening with the Prime Minister, but only touched on those elements in it that related to my immediate administrative problems.

In regard to the construction of a string of military camps, I assured Mr. Dias that I will faithfully carry out his instructions and ensure that all that I had to do to facilitate their construction will be done. Actually, within the first year of my tenure almost all of the infrastructure for setting up the camps had been completed, and by the time I relinquished office in 1966 all of the camps were up and running.

It is a pity that Dias’s vision of a future armed Tamil uprising and of India’s intervention on the side of the rebel cause, has not been properly chronicled and my references to it in this chapter are a paltry substitute.

At this point however, I want to refer to three other components of Dias’s remarkable strategic thinking which he had shared with me when I met him a few weeks earlier over lunch at the GFH and which I have so far omitted to mention, which further reinforce his claim to be Sri Lanka’s greatest strategic thinker of modern times.

The first component was, that his plan to set up a chain of military enclaves in the North had another strategic aim besides the long term one of throttling an armed uprising by the Tamils, and that was, to pre-empt another coup such as had been attempted in 1962. He was resolved that he will not leave room for another adventure by the military, whom in general, he held in contempt. By dispersing it as far as possible from Colombo, away from Echelon Barracks (which were still functional at that time) and Panagoda, and making it logistically impossible for them to mobilise and co-ordinate a military takeover in the capital, he placed a stopper on the army.

The second component was a plan to strengthen relations with Peking as a countervailing power to India and neutralise the latter’s overweening influence in Sri Lanka’s internal affairs. He said that he was hoping to arrange for Mrs. Bandaranaike to visit China shortly, even though he held Marxists and Communists with a terrible loathing.

The third component was a plan to clean out the military’s top command as far as possible of elements he considered incapable of patriotism, and that was principally the Roman Catholics, and to raise new infantry regiments which would owe their allegiance to Mrs. Bandaranaike, the Sinha Regiment being the first of them. The Sinha Regiment was Mrs. Bandaranaike’s Praetorian Guard. (In Roman times the Praetorian Guard was the elite Legion, always positioned in Rome, to guard the incumbent Emperor)

I did not share then, nor do I share now, Dias’s world view based on race, which I thought was tubular and divisive, more likely to aggravate conflicts and fragment the nation, rather than help build a harmonious polity. However, I want to emphasise again, that in its strategic aspects, given his assumptions, the Dias paradigm is breath-taking for its prescience and sheer brilliance. In his capacity as the Secretary for Defence it was entirely legitimate, and obligatory on him to plan well ahead for the suppression of any anticipated armed rebellion and to try and neutralise intervention by India, and he fulfilled that obligation as no one else had done before him. Sri Lanka is much in his debt.

However, and I must underscore this again, I also think that it was better had he tried to abort that uprising by removing the factors that were likely to cause it, than assume it to be inevitable and prepare militarily to combat it.

Back to the barricades

The testing time for my vision of conciliation and accommodation, as opposed to Mr. Dias’s vision of unrelenting confrontation, was only a few days away. I had to hasten back to Jaffna as the barricades beckoned and the crunch seemed imminent!

Excellent. Wish long life. Happiness. And joy. Thanks.