Enduring mysteries surround a 6th century Tamil poet-saint and her work.

Between the 5th and 6th centuries in the region now known as Tamil Nadu, emerged an intensely emotional devotionalism focussed on one of two gods, Vishnu or Shiva, that eventually came to be known as the Bhakti movement. A number of saints composed impassioned poetry, praising their chosen deity as immanent in sacred centres across the Tamil land. Temple inscriptions show that many of these hymns were popular among the masses. Myths and legends grew up around the saints as well, and they too became objects of popular veneration. Hagiographies of the saints were composed in both the Vaishnava and Shaiva religious traditions in the early centuries of the second millennium. It is likely that several of these canonised saints were not necessarily historical figures, but creations of the popular imagination. And while some of the poet-saints are evidently historical in that they have left behind compositions, the stories we know of them may be entirely mythical. Interpreting Devotion: The Poetry and Legacy of a Female Bhakti Saint of India focuses on one such saint, called Karaikkal Ammaiyar in popular tradition, on her poetry, and on how the two have been understood by others. For the author, Karen Pechilis, these three foci converge towards a central question: how devotion is understood and interpreted.

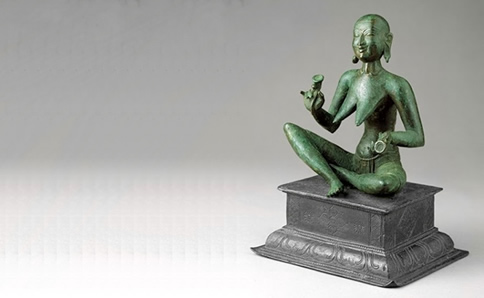

The poetry under consideration is the earliest of the Tamil Shaiva Bhakti corpus; in three of the four poetical compositions, the poet signed herself/himself Karaikkalpey, ie., ghoul from the town of Karaikkal. While this poet lived sometime in the 6th century, it was in the twelfth century that a Chola court poet, Cekkilar, composed his hagiography of 63 Shaiva saints. All but three of these canonised saints are men, and two of the women saints seem to be included in the list essentially due to their association with one or the other of the male saints. Karaikkal Ammaiyar is therefore a particularly interesting subject of study as she is apparently the only female poet-saint in the Shaiva hagiographic tradition.

In several poems the poet speaks of herself – and here I am following both the millennium-long Shaiva tradition and Pechilis herself in continuing to use the feminine pronoun – as watching the fearsome dance of Shiva in the cremation ground in Tiruvalankatu, surrounded by macabre, flesh-eating ghouls, at least some of whom are specified as female. Though none of the signature verses in the hymns identify the author as a woman, Cekkilar decided, for reasons we cannot fathom, to treat this third-person representation of the female ghoul as a self-portrayal by the poet, and accordingly drew a portrait of a woman who was transformed from a beautiful wife to a skeletal, ghoulish creature who chose to spend her days – and nights – celebrating Shiva’s dance in the cremation ground. Pechilis demonstrates why this identification is problematic through an examination of the subjectivity of the poet and of the ghoul as seen in the poetry itself. Drawing on insights from important feminist studies, she also shows that the themes and images in the poetry do not resonate with those by other women authors. While Pechilis does not pose the question of why medieval hagiography chose to attribute feminine gender to this poet, it is significant that she engages with this issue at all, for most scholarly works on Karaikkal Ammaiyar that I am familiar with have tended to take Cekkilar’s account at face value. According to the hagiography (Pechilis consistently refers to it as biography, and to Cekkilar as biographer) Punitavati was a beautiful and devoted young wife whose husband one day sent home two mangoes that he wanted to be served with his lunch. A Shaiva mendicant happened to come begging and Punitavati fed him one of the two mangoes. At lunchtime, after eating the first mango, the husband asked for the second. Distressed at being unable to perform her wifely duty, Punitavati prayed to Shiva; a mango miraculously appeared in her hand, which she served her husband. Noting the marked difference in taste, he questioned his wife, who confessed the whole, and on being compelled by her husband to prove it, prayed and produced a mango again which, however, disappeared as soon as the husband reached for it. Convinced of his wife’s divine nature, he abandoned her and remarried in another town. Eventually, on learning of it, Punitavati prayed to be rid of her beautiful physical form and to be granted the boon of worshipping Shiva eternally in the cremation ground. It is this devotional experience that she recorded in her rather startling poetry that paints vivid images of the cremation ground. Cekkilar also tells us that the saint made a pilgrimage to Mount Kailash, climbing upside down on her hands so as not to defile the sacred mountain with her feet. Touched, Shiva rose to welcome her, addressing her as ‘Amma’ (mother); she in turn called him ‘Father’. From this episode comes the name by which the saint is known in the tradition, ‘Revered Mother from Karaikkal’.

Arputat Tiruvantati, poem 98 Would the palm of your handturn red from the flames dancing in it?Or would the flames turn redfrom the beauty of your palm?You who dance on the fire where the pey live, bearing bright flames in your palm with anklets ringingMake your reply to this.

Ammaiyar relates to other devotees through several strategies in her poetry—by mentioning ‘them’, and by directly addressing them. Pechilis suggests that the use of the first-person plural pronoun in the poems could be a linguistic device indicating simply ‘I’, but could also refer to the community of devotees of whom the poet considered herself a part. In Ammaiyar’s poetry, visual references to Shiva through description of his mythological deeds evoke his divine power. The poet both loves the deity – who she personally addresses in numerous poems as ‘you’ – and considers herself bound in service to him. It is significant that her devotional subjectivity is one where she questions her lord. Pechilis examines the poetry carefully in order to give the poet’s own voice priority in understanding her ideas, her interests and her self. This is critical as the hagiographer’s narrative has dominated her representation to the degree that most Tamils are rarely familiar with her poetry despite intimately knowing and engaging with her ‘life-story’. While the hagiography ends with the saint-poet sitting blissfully at the feet of Shiva, assured of salvation, the Arputat Tiruvantati, Ammaiyar’s major work, does not suggest such complacent self-assurance, but an active engagement with the object of the poet-saint’s devotion, through a questioning heart and mind. In seeking to understand the significance of the multiplicity of the lord’s forms, her poetry shows hers to be a philosophical quest rather than a simple celebration of mythology. Letting the poetry speakThrough a masterful analysis of Sanskrit and Tamil myths around Kali and the dance of Shiva, Pechilis shows that Ammaiyar’s profession of desire to witness Shiva as Dancer weaves together both yogic and devotional perspectives on Shiva’s cosmic dance. Pechilis’ analyses of representations of the cremation ground, fearsome goddesses and avenging females in earlier Tamil literature (both Sangam poetry and post-Sangam epic), and her in tracing the antecedents of this feature in Ammaiyar’s work as well as in the creation of Ammaiyar’s life-story by her hagiographer, undoubtedly break new ground.

Arputat Tiruvantati, poem 99

Answer me:Is the dance you performadorned with the five-headed cobrawho spits firewatched by the lady with young breasts like bowlsor by the circle of pey at the fiery cremation ground?

In her minute examination of Ammaiyar’s work, Pechilis notes the relative frequency of references to different mythological themes (such as the preponderance of Shiva as Dancer, followed by Shiva as bearer of the Ganga and Shiva as bearer of poison). It has been noted that in composing the Periya Puranam, the hagiography of the Shaiva saints, Cekkilar probably wished to refute, or at least to downplay, the frightening and sexually suggestive forms of Shiva satirised by contemporary Vaishnavas and Jains, and accordingly sought to portray him as a fatherly figure. Pechilis demonstrates Cekkilar’s strategy to achieve this in the narrative of Karaikkal Ammaiyar; the fine details in the episode of the saint meeting Shiva on Kailash could have served to underline Shiva’s fatherliness. I wonder if it is in the same light that Pechilis interprets verse 27 from the Arputat Tiruvantati, where Ammaiyar requests that her lord adorn himself with a golden necklace in place of the cobra on his chest. This is similar to several poems where the poet advises the lord to remove his fierce ornament at least when he goes begging so as to not frighten chaste women. Pechilis suggests that the speaker is concerned here that the lord’s body should display emblems which have a positive social resonance, and that she may be responding to challenges to Shaivism. Another possible interpretation that she suggests is that the poet may be indicating that the fearsome aspects of the lord’s appearance need not be – and indeed, are not – obstacles to the devotees’ love for him. I agree with the second interpretation but have my reservations about the first. The overwhelming tone of these verses appeared to me to be ninda-stuti: seemingly reviling the lord’s choice of a cobra and a garland of bones as ornaments, or, indeed, his unconventional appearance as a nude beggar, the poet may actually be asking her listener/ reader to share her wonder at the unknowable nature of her lord. She may be drawing our attention to his uniqueness and majesty such that the more usual accoutrements of gold that are necessary for glory for mortals, or perhaps even for lesser gods, are of no account to him. Tracing the literary antecedents to the creation of Karaikkal Ammaiyar’s persona, Pechilis brings together a wide range of sources, and shows how different motifs from the Tamil epics Cilappatikaram, Manimekalai and Nilakeci, were used to create the picture of a chaste wife and eventually an ascetic in the tale of Karaikkal Ammaiyar. The examination of the patriarchal constructs of women and women’s religiosity that underlie the narrative is equally insightful.

Tiruvalankattut Tiruppatikam, Poem 8 In this fearsome burning ground the heat bursts the tall bamboo popping its white pearls and desiccated pey clamor as they gather to feast on corpses while the enchanter dances beheld with wonder by the daughter of the mountain lord.

The chapter on modern festival performances celebrating Karaikkal Ammaiyar was, despite being the easiest to read, with, occasionally, something of the timbre of a journal or a letter to a friend, no less scholarly. Through a detailed description of the events of two different festivals in honour of the saint, in two different temple towns associated with her by hagiography and thence in popular tradition, Pechilis brings out the difference both in emphasis and in factual detail between the written and popular traditions. While the saint’s marriage gets but a brief notice in the Periya Puranam account, (and is non-existent in her poetry), it is the focus of a major celebration in the saint’s hometown, with (especially women) members of the festival public engaging most intimately with her good-wifely character and praying for her intercession in marital concerns. Similarly, in the festival, the Shaiva ascetic-beggar of medieval literary accounts is transformed to Shiva himself in disguise. These adaptations, Pechilis suggests, are part of the continued negotiation of the community of devotees with the primary devotional subject of this study and with her devotional subjectivity. A complete translation of the works attributed to Karaikkal Ammaiyar is appended to the book, as is a translation of Cekkilar’s hagio/biography of Ammaiyar. The translations are, in a word, wonderful. Pechilis has, in fact, undertaken two different translations of several of the poems – one which prioritises the source language, ie., Tamil and another that strives for accessibility in the target language, ie., English. The appendix, which is where the poems are translated in their entirety, is, according to the author, truer to Tamil than to English. I assume this means that faithfulness to her source was more critical than poetic quality in English. But, oh! The poems read beautifully, and it is only on repeated comparison with the same stanzas in the ‘target language’ translations that I could sometimes figure out the superiority of the latter. An excellent piece of scholarship from someone who could well have been a poet.

Bharati Jagannathan teaches history at Miranda House, University of Delhi. She has studied the Srivaishnava religious tradition in early medieval Tamil Nadu, and is currently looking at women in the Srivaishnava tradition and in the Ramayana. She also writes fiction, both for children and adults.