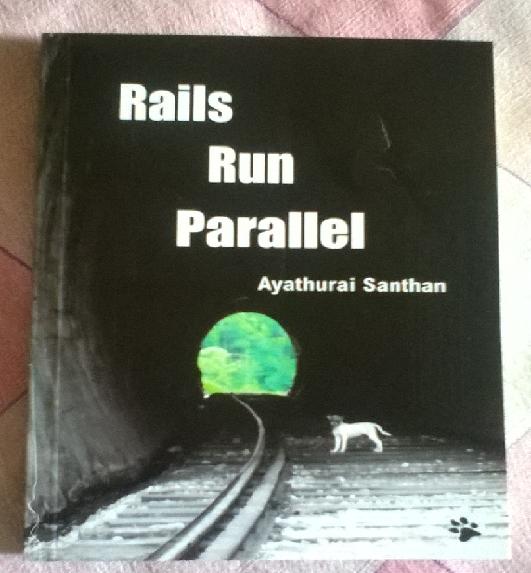

by SLWakes blog, April 18, 2015

Ayathurai Santhan’s Rails Run Parallel is his follow up to The Whirlwind(2009), where the focus was on the arrival of the IPKF to a small Northern village which is thereupon dragged into a divisive power struggle between rival militants. In his new novel, Santhan based his narrative in the South, looking at the lives of state-serving Tamil youth – many of them with Jaffna roots – at the wake of the 1977 riots. The main story evolves around Sivan, a young trade unionist who, at the beginning of the novel, is caught in a dilemma whether to relocate to Jaffna or not: other likeminded youth – provoked by circumstances – are boarding buses and trains, evacuating the capital in face of concentrated assault from state-patroned goons and squads.

Sivan, in that capacity, represents a class of Tamils, who, by the 1970s, had reached a middle position in that proverbial ladder of social mobility. As such, Sivan’s anxieties, indecisions and complexities become the fears and dilemmas of a class of bureaucracy-related learned Tamils whose very livelihoods and careers are ruptured midstream at the wake of a string of communal riots commencing with 1977.

In the novel, Santhan, subdivides the text into two sections – 1977 and 1979. In the former, we are familiarized with the “fleeing” of Colombo, at the wake of anti-Tamil activism: a fleeing that is difficult – for life has been built or half built around jobs and fortunes offered by the metro – but is inevitable, given the strong antagonism felt by the Tamil community. Here, Sivan, along with many others make a skeptical removal in the wee hours of the morning – almost as if they are robbers moving between shadows before daylight – in search of Northern sanctuary as a retreat and as a fall back option.

Santhan’s protagonist Sivan, along with his friend Varathan and their collective families, head for Colombo railway station at the earliest daylight in a hired cab. The cab driver is described as one whose appearance and dress disturbs the “fugitives”; for, he is felt to be the kind who may turn around and take advantage of the vulnerable position of the fleeing Tamil families. In fact, this episode is one of the most moving and revealing in the text, where the said taxi driver – in spite of his “suspicious” appearance – becomes one of the empathetic agents of the (as implied) Sinhala community to the plight of the Tamil. He, when offered, resists over-payment and also genuinely commits at attending to Sivan’s injured finger, which is caught in a door-jamming accident at Pettah.

Santhan’s protagonist Sivan, along with his friend Varathan and their collective families, head for Colombo railway station at the earliest daylight in a hired cab. The cab driver is described as one whose appearance and dress disturbs the “fugitives”; for, he is felt to be the kind who may turn around and take advantage of the vulnerable position of the fleeing Tamil families. In fact, this episode is one of the most moving and revealing in the text, where the said taxi driver – in spite of his “suspicious” appearance – becomes one of the empathetic agents of the (as implied) Sinhala community to the plight of the Tamil. He, when offered, resists over-payment and also genuinely commits at attending to Sivan’s injured finger, which is caught in a door-jamming accident at Pettah.

The second section, set in 1979, follows a coda of two years. By now, Sivan has returned to Colombo and is back at his job in the state sector. This part of the novel preoccupies itself with Sivan being sent to represent his own clerical order, in a case where a due promotion has been arbitrarily overruled. Much of the section follows Sivan who goes to the main office of the related bureaucratic bigwig who is in charge of the promotion procedure and in him committing himself to the task of getting the anomaly removed. Later, he returns to his office, where all fellows – in spite of race or ethnicity – congratulate him. This is a starkly contrasting scene to how Sivan, in the wake of the 1977 riots, is isolated by the Sinhala workers of his unit.

One of Santhan’s strengths in his long career as a writer is his ability to frame in the impulse of the soil: how ordinary people react to and are affected by situations and conditions which overwhelm them. This is notable in almost all works of Santhan – work that reflect on and chip into politics in a committed way, but not in a bid to suck the life blood off a historical moment; like what most writers reflecting on Lanka do with 1983. For Santhan, the human plight that is caught in and is overwhelmed by the political atmosphere is a reality that precedes how “politically correct” one’s choice of historical incident must be. As such, his focus on 1977 and 1979 stand out. The bemused may ask the question – “why not 1983?” (specially, when Santhan, with 77 and 79, is so close to that year of a Black July), but the answer to such a question is there in Santhan’s narrative itself: 1977 is – in a discursive reading of violence against the Tamil – perhaps more crucial in a holistic investigation of a process in which “1983” is merely a spillover point.

Santhan’s text is a “quiet” weave – save where he meticulously looks at how people are troubled and caught in complex moments, lacking decision and conviction. Much of the displacement and uncertainty we encounter in the novel is channeled through the psychological icebergs peoples hit. The psychological dilemma is given precedence – and is used as a reflection of the disruptive patterns operating in the world outside, of which the Tamil community at that point is a directionless victim. Whatever violent or turbulent “activity” is either recorded or recollected – in any case, they happen “off stage”. Implication and nuance play crucial roles in Santhan’s weave, thus presenting the political commentary in a more intense form.

One example is when Sivan meets Ravi – a fellow from his own Northern Tamil high school, who is now a bus conductor in a densely Sinhala area. Ravi is seen speaking to a woman in Sinhala, even when the woman bears signs of being a Tamil. When asked, Ravi explains that he has to use Sinhala as he has to operate in a largely Sinhala environment. This explanation disappoints Sivan, for in Ravi we meet one who has compromised one’s culture and identity in the way of getting by more smoothly in the Sinhala dominated South. Yet, the episode also reveals the compromises and complexities the Tamil identity meets and how their careers, as a whole, are punctuated by many allowances they have to make: some allowances being too close to their hearts as cultural agents.

Santhan subtly criticizes the division among the same clerical lower middle class – the clerics at the government office of which Sivan is employed. This is true in the contemptuous treatment of the Tamil clerks by their Sinhala cousins in the event of “1977”. Santhan lays heavy emphasis on this petty division / difference in treatment among the clerks ignited by racial hatred, while in “1979”, Sivan stands up to champion a “common cause” which secures the promotions and rights of the clerks as a group, irrespective of ethnicity or identity. In a parallel trajectory, Shobhasakthi’s Traitorpresents us the memorable Pakkiri, who is in confinement with the protagonist Nesakumaran Ernest. Pakkiri, said to be of the deep Left, preaches to his fellow inmates in Welikada (weeks to July 1983) that the “next riot” of the Sinhalese will be against their own kind – a rebellion against the Sinhala elite. Pakkiri also forecasts that the Sinhala prisoners will be the custodians of the Tamil inmates at Welikada in such an event: Pakkiri’s theory-laden analysis is proven fatally wrong. In common, both Shobhasakthi and Santhan strongly underline the absence of “class” or such a consciousness among the lower social rungs in their violent political upheaval. The “class” aspect, which could have been the binding factor and the do all and the end all of progressive social transformation, is demurred in the face of petty, divisive, racialist vitriol.

Rails Run parallel is a smooth, easy read. Santhan is an unassuming story teller, who doesn’t lose his craft among the theatrics and gimmicks which most writers – specially, writers who deal with sensitive subjects as ethnicity and violence etc – parachute into their trade. Nor is Santhan’s a story with “big action” and climactic histrionics. His focus is neatly on the mundane and the ordinary – a conscious effort to grasp the mind and anxiety of the Colombo-based Tamil middle/lower middle class. As such, Santhan strives to – and succeeds in – capturing a “local resonance” and a “response of the soil” to the political and social alienation of which both Northern and Southern Tamils were victims. Santhan’s Rails Run Parallel is a rare moment of unambitious honesty in a story teller trying to represent the above: a far cry from those who make writing stories out of the Lankan Civil war a livelihood and the means of a quick buck.