A decade after the Sri Lankan civil war, a former UN worker revisits the lives of those he left behind on the island through a graphic novel

by Amrita Dutta, The Indian Express, November 17, 2019

In September 2008, as the war between the Sri Lankan army and the LTTE (Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam) mounted in the country’s north, UN workers began moving out of Kilinochchi, Vanni. Benjamin Dix was one of them. He had arrived on the island in 2004 to help the victims of the devastating tsunami, and had stayed on as the conflict worsened. The UN’s departure from the country, as the Sri Lankan government gained control of areas under the LTTE, left many Tamilians vulnerable. “I left Vanni with a huge collection of interviews, photographs and reports, along with my own lived experiences and relationships within the Tamil community…. A deep sense of shame and guilt engulfed me as I drove out of Kilinochchi in the last UN convoy on 16 September 2008,” recalls Dix, who lives in London.

A year later, while working in South Sudan, he followed the final march of the Sri Lankan army. Once Kilinochchi fell, around 300,000 civilians were pushed into a slender no-fire zone on the coast. While the LTTE used the people as cover, the Mahinda Rajapaksa government’s promise of no civilian casualties proved to be hollow. “I received weekly messages, through various channels, that another friend or colleague had died. The Sri Lankan government created a propagandist narrative that they were ‘rescuing civilians from a hostage situation’. But by removing international witnesses and media and convincing the world they were not using heavy weapons on civilian targets, they managed to not just eradicate the LTTE but also kill thousands of Tamil civilians and deeply damage, but not destroy, the very fabric of their cultural identity,” says Dix, 43.

For the international media, the war remained largely a story of “freedom” from a terrorist organisation. But Dix knew that did not take into account the hundreds of displaced Tamilians, on the move, dying as shelling continued; or of the many others who were “disappearing” into internment camps. In a bunker in Kilinochchi, he had read his first graphic novels, Art Spiegelman’s Maus (1980) and Joe Sacco’s Palestine (1993). “I saw how complex and distressing histories could be told in innovative ways. I realised at the time that I wanted to turn what I was seeing in Vanni into a graphic novel, depicting the displaced people, the carnage, our impotence at the UN and the many stories of human suffering,” he says.

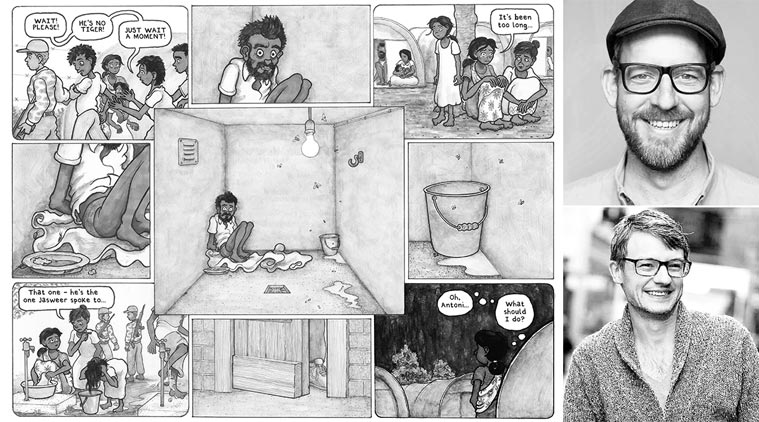

The result is the just-released Vanni: A Family’s Struggle Through the Sri Lankan Conflict (Penguin Random House), which Dix wrote with artist Lindsay Pollock, 39. It tells the story of a family in Chempiyanpattu —Ranjan and Antoni Ramachandran, and their children Theepa and Michael — as they and those around them are wrenched out of their lives. Their journey from relative safety to displacement, terror and abuse was based on interviews with 20 families in England, Switzerland and India.

“At the organisation Freedom From Torture in London, we met Tamil people who kindly — stoically — shared their experience of torment at the hands of the Sri Lankan state. There were no photos or filmed record of these events. I had to listen with concentration, and try to imagine what it must have looked, smelled and felt like in those locked rooms. I tried to visualise this as a living nightmare for those people, who were bound and helpless,” says Pollock. Neither of the artists went to Lanka for their research, for fear of the risk it would mean for the Tamil people there.

“Lindsay and I travelled to Tamil Nadu and spent a lot of time interviewing Tamil refugees, many of whom I’d known from my time in Vanni. We rode around the interiors of Tamil Nadu on a Royal Enfield bike so Lindsay could see for himself certain details of daily life to be able to illustrate rural Tamil life with a sense of authenticity,” says Dix.

The visual experience of violence can deaden the viewer, and make empathy difficult. “‘There’s no such thing as an anti-war film’ is a quote often attributed to (filmmaker Francois) Truffaut. I thought about that a lot. I was concerned not to make the violence either glamorous or ‘exciting’,” says Pollock. The Sri Lankan war was fought before the advent of smartphones and cheap video technology, which “allowed the Sri Lankan government to effectively black-out their actions by excluding journalists from the war zone”.

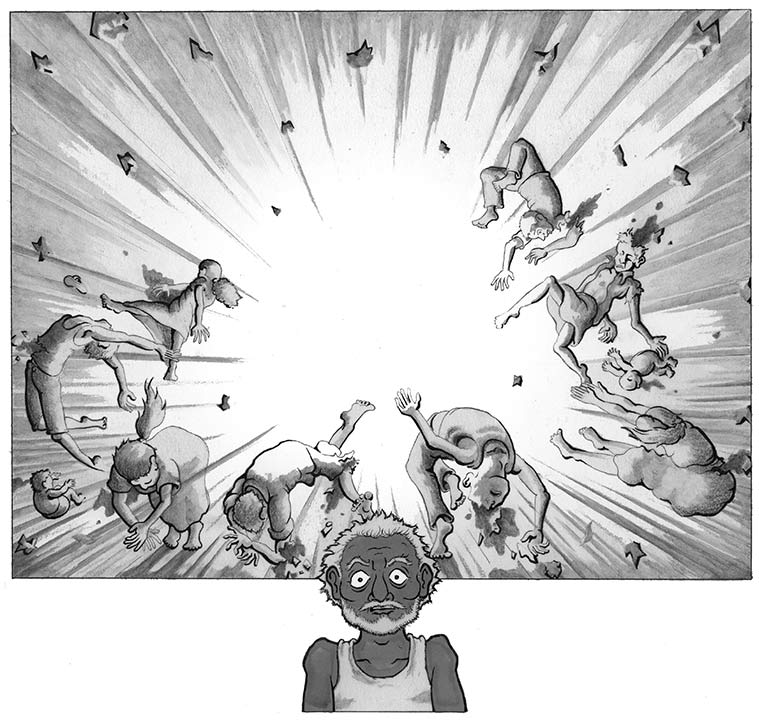

But on the internet, an archive of photographs of the brutality survives. “People — civilians — turned to meat by heavy weapons or coldly executed and left to rot. At the beginning of the project, I was transfixed by the pictures. I thought they spoke a truth more profound than anything I could draw. The enormity of suffering was stupefying to contemplate. What more was there to say? But, in fact, the horror obscures so much. Principally, the humanity of the dead. And the humanity of the living, the survivors. All had another life, another identity, before the war,” says Pollock.

Details from the graphic novel.

Details from the graphic novel.

The spirit of straight-up reportage animates Vanni, rather than the complex, allegorical storytelling of, say, Maus. The narrative begins in the relative calm of pre-tsunami north Sri Lanka, where the Tigers blend easily with people. But by limiting itself to a linear narrative that climaxes in the final days of the war, Vanni is often overwhelmed by the relentless violence — so much so that the reader’s connection with the characters, ceaselessly on the move, is often hard to sustain. It is in the art that the book finds some repose — in silent panels where grief takes over, or in blank speech bubbles which indicate life in an alien, incomprehensible land; and the images of men, women and children living out their grief and trauma. “I leaned away from the specific horrors I heard about — the pulp and viscera. I tried to replicate the range of emotions — the shock, fear and grief, but also the stoicism, kindness and tenderness of people in the face of tragedy and terror,” says Pollock.

For the Tamil people who survived the war, both within Lanka and without, there has been little justice. “Every conflict is important to remember, if only to help the next generation learn from past mistakes, although this notion seems tragically hollow given the current state of global politics. Sri Lanka is especially important, as 10 years on, there still has not been any credible sense of closure and justice for the victims. The lack of respect the state shows towards their people sets a dangerous precedent,” says Dix.

Vanni also hints at the difficult lives of the Tamil diaspora in countries where their trauma is incomprehensible and unacknowledged, for the most part. The survivors told Dix and Pollock that seeking asylum in those countries was as much a horror as the war itself. “The laws, culture and bureaucracy of asylum-seeking are utterly heartless. We heard about people who had survived the horrors of the war, only to hang themselves in godforsaken detention centres, thousands of miles from their homes and loved ones,” says Pollock.

In the pages of Vanni, the artist creates the stark loneliness of Antoni, who survives torture and war, but lives on the margins in London, while his family lives in peril in Tamil Nadu. “I had only a few pages to try and evoke the alienation and despondency of a survivor abroad. To be a stranger in a strange land, terribly alone, fearful for loved ones, helpless to aid them, and gripped by roiling, untreated PTSD. I thought hard about how to depict scenes of perfect banality — a high street, a bus — as they might appear to such a survivor. The streets full of incomprehensible visual clutter — crass and intrusive advertising, confusing signs and people speaking all around but none who can be understood. And finally, the bare, empty room of the asylum accommodation; a place of nothing but loneliness and memory. The picture of Antoni’s empty room — not unlike a cell — is my proudest in the book,” says Pollock.

This article appeared in the print edition with the headline ‘Written in the Scars’