by Anjali Siva, August 14, 2004

This past summer I went to Sri Lanka, for the first time in ten years. But what affected me was going to Thamil Eelam, for the first time ever. I spent three weeks in this war-torn and impoverished area, marveling at the spirit of the Thamil people.

During my first week, I walked daily to Navam Arivu Koodam (Center for New Knowledge) , the home for injured Tigers. These soldiers were not embittered by their condition, some without arms or eyes. They were accepting and ever-supportive of the cause they would give everything for, and almost did. This is where I learned the proper pronunciation of Vidithalai Pulegal (they were more eager to teach me Thamil than to learn English), but more than that, this is where I began to understand the meaning of Freedom Fighter.

Though I had known the Thamils had been persecuted by the Singhalese, forced into a war to defend themselves, I never really understood the meaning of this. Born and raised in America, it was difficult to comprehend the genocide the government openly inflicted against its own citizens, the Thamil people. I knew the civil war had lasted decades and 17,500 LTTE-soldiers and over 100,000 Thamil civilians were dead, but I did not understand the meaning of these numbers…until I saw the battlefields and met the soldiers.

I saw Elephant Pass, the site of the 33-day battle, in which 1,000 Tigers forced 10,000 of the Sri Lankan Army to flee. I saw the trees with their trunks burned black and their heads loped off by the constant barricade of bombs. I saw the signs warning of the possible mines still active in the area, preventing me from wandering too far from the bus. Gazing out over the tranquil waves, marveling at the simple beauty of the sun’s reflection on the water, it was too easy to forget about the final sacrifice many cadres willingly gave to secure the safety of their people. The juxtaposition of a rusted army tank upon the soft white sand was a gruesome reminder of the many dead, which the serenity of the beach belied.

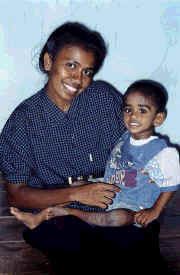

Gurukulam Girls Orphanage, Vanni ,summer 2004

The playful personalities of the soldiers also belied their intense devotion to the cause of Eelam’s liberation. These Accas and Annas were amazingly kind and unique. They joked with me, good-naturedly making fun of my broken Thamil, stubbornly refusing to let me pull my own water from the well, mischievously teasing me for the arachnophobia that made me chase spiders away with a big yellow broom. The soldiers were like older sisters and brothers, so comfortable and familiar with me though we’d only known each other a few days. In this time of peace they were able to reveal the individual beneath the army uniform. But who they were was very much wrapped up in the uniform. Because for them, it was not simply a uniform. It was a tangible representation of their fervent thirst for Thamil Eelam, a place where Thamils would be safe from rape, murder, and all the forms of persecution that are devastating the Thamil people, culture and way of life.

It was these soldiers who made my experience so poignant, who jarred me out of my American-born-and-bred-distance from a struggle relatively incomprehensible until I visited the homeland. Until I witnessed the destroyed buildings, schools and homes alike, witnessed the one-room shacks displaced refugees were forced to exist in, witnessed the orphanages teeming with surprisingly cheerful children, and the gentleness the Accas (sisters) and Annas (brothers) revealed in playing with the children. These soldiers made the fight more personal, forcing me to the realization that the 17,500 soldiers already dead was a colossal number of Accas and Annas who likely bore witness to the deaths of family, friends and neighbors, comprising the 100,000 civilians murdered. When we visited one of the many cemeteries for fighters, one Acca calmly rested her hand on one marker, saying, “This is my brother.” They have not recovered his body yet, so he has no coffin, only a headstone.

Kanhtarooban orphanage, Vanni, summer 2004

Another Acca, who has been fighting for liberation half her life, began to cry when she told me of the bombing of her house when she was only nine. As she recalled the horrible multitude of crimes she had seen, she told me she never wanted to fight, she was forced to fight by the universal desire to protect one’s self and one’s family.

The orphanages, already full of children whose parents were either killed in the struggle or who could not afford to give them adequate care after the war virtually decimated the economy, will only increase in number until the struggle is over.

Though they are already stretching every rupee as far as it can go, there is an alarming shortage of resources. For example, the Deaf and Blind Orphanage has enough musical instruments, but no one to teach how to play them.

And at Gurukulam, a girls’ orphanage, an English teacher ignorantly taught that a big, scary creature children fear is a “victim,” not a “monster.” And at Kanhtarooban, a boys’ orphanage, there is an adorable baby boy, who was brought to the orphanage when he was just three months old — too young to realize the loss of his family and the loneliness ahead. Like him, the budding country of Thamil Eelam has many needs, compelling enough to bring tears from even the most jaded American. Its first need is independence, which the soldiers will proudly sacrifice everything for — even if in return for their selflessness, courage, and spirit, they receive a headstone.

Oxen, Tamil Eelam, summer, 2004

Maveerar cemetery, Tamil Eelam, summer 2004