by Sachi Sri Kantha, June 28, 2017

by Sachi Sri Kantha, June 28, 2017

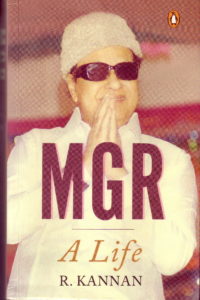

Book Review: R. Kannan, MGR – A Life, Penguin Random House India Pvt. Ltd, Gurgaon, Haryana, 2017, 495 pages, 599 Indian rupees.

The influence of movie stars as popular heroes has been a theme of academic study in America since the second half of last century. For instance, for his Ph.D. thesis in sociology, submitted to the University of Chicago in 1951, Frederick Elkin defined a popular hero as a person of prominence in the society who is the object of veneration or idolization and studied the attributes projected by 12 popular Hollywood stars of that era. These were, Betty Grable, Greer Garson, Bette Davis, Katherine Hepburn, Rita Heyworth, Lauren Bacall, Jimmy Stewart, Clark Gable, Humphrey Bogart, Van Johnson, James Mason and Errol Flynn. But, critical studies of this type were late to begin on Indian movie stars. One of the pioneers was Robert J. Hardgrave Jr. who had focused on M.G. Ramachandran’s (MGR, 1917-1987) movie career, as a component of his study on the rise of the Dravidian movement (Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, aka DMK party, led by C.N. Annadurai) in 1960s.

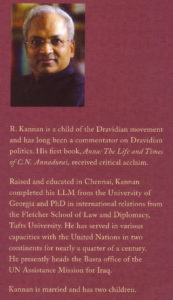

Kandy-born MGR’s subsequent popular success in Tamil Nadu politics from 1967 to 1987, did stimulate the interest of few serious scholars to explore the path of his prominence. This year being the birth centenary year of MGR, a new big biography on him in English, authored by Rajarathinam Kannan, had been released. After mentioning two previous biographies on MGR in English, that of M.S.S. Pandian’s The Image Trap: M.G. Ramachandran in Film and Politics (1992) and K. Mohandas’s MGR: The Man and the Myth (1992), as well as that of Kalaignar M. Karunanidhi’s six volume autobiography in Tamil, Nenjuku Needhi, in his preface, Kannan provides the objective of his exercise as follows: “It seeks to fill the void of a dependable, standard biography on MGR in English.” This biography in English, is the largest and most complete, among all the previously published MGR biographies in English. The text consists of 395 pages, in 8 chapters. 100 pages contain detailed explanatory notes, bibliography of 104 primary and secondary sources, and an index of 25 pages.

In the past 50 years or so, the entertainment value of MGR’s cinema career as well as his services (or lack of) to the Tamil ethnics had been studied and critiqued by academics such as Eric Barnouw (1908-2001), K. Sivathamby (1932-2011), Robert Hardgrave Jr. (b. 1939), Barbara Harris-White, M.S.S. Pandian (1958-2014), Sara Dickey and yours truly. To his credit, Kannan had relied on the materials offered by these academics, and furthermore had invested much time and energy in doing his own research for this book. It can be asserted that having authored previously a splendid biography on MGR’s mentor, ‘Anna: The Life and Times of C.N. Annadurai’ (2010), had come in handy for Kannan to continue along those lines.

Kannadasan’s Thoughts on Karunanidhi and MGR

Kannadasan’s Thoughts on Karunanidhi and MGR

What followed after Anna’s death in February 1969 had been recorded by posterity by poet Kannadasan (1927-1981) in the second volume of his autobiography. He had opined that it was MGR’s hand that made Karunanidhi the winner in the power struggle against Navalar V.R. Nedunchezhiyan (1920-2000) that followed. In Kannadasan’s words, “Knowingly or unknowingly, Mr. MGR sided with Karunanidhi. When it became known that MGR supported Karunanidhi, the number of those who shifted [their allegiance] to him increased. Because of this, it became easy to ignore Nedunchezhiyan’s claims for seniority and make Karunanidhi the leader. In those days, Karunanidhi was meeting MGR in the morning and evening. At the meeting of party’s MLAs, Karunanidhi was chosen. Navalar [Nedunchezhiyan] and Madhavan could only shed tears in front of Anna’s grave. Before the wetness dried in the grave, it appeared that party will split into two. But, Karunanidhi had saved that due to his sagacity. Karunanidhi’s horoscope should have been powerful then. Only after Karunanidhi became the Chief Minister, the Congress Party’s split came into open.”

Though Kannadasan had been critical on MGR’s many deeds, as presented by Kannan in quite a few paragraphs, Kannadasn was objective in recording the above fact that Karunanidhi owed his elevation to chief minister position to MGR. The timing of this revelation was apt, because when the poet serialized his autobiography in the pages of Kalki magazine in mid 1970s, MGR and his newly founded breakaway party Anna DMK was at the receiving end of Karunanidhi’s cryptic aggression.

Leaving the first 10 years as a child, remaining 60 years of MGR’s 70 year life can be conveniently split into two disproportionate periods; 40 years (1927-1967) as a stage and movie actor, and 20 years (1967-1987) as a politician. Final 10 years of his life was spent as the Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu, in three consecutive terms (1977-1980, 1980-1984, 1985-1987). Kannan’s biography is particularly strong on the final 20 years of MGR’s political life, covered in the last four chapters, comprising 250 pages of text. First 50 years of MGR’s life as a stage and movie actor are covered in the first four chapters, spanning 144 pages.

For information on MGR’s actor phase of life, Kannan had relied primarily on MGR’s two volume autobiography, ‘Naan Yaen Piranthaen?’ [Why I was Born?], first serialized in the Ananda Vikatan magazine between 1970 and 1972. Unfortunately, due to MGR’s expulsion from the DMK party in October 1972, this serialization came to an abrupt halt. Apart from this primary source, author has also relied on secondary sources such as autobiographies of stage drama and movie personalities such as Karunanidhi, poet Kannadasan, script writer Arurdhas, director Krishnan Panju, actor-politicians Sivaji Ganesan and S.S. Rajendran, character actor V.K. Ramasamy. actor-journalist Cho Ramaswamy, poet Rangarajan (aka Vaali), producer M. Saravanan, MGR’s assistants K. Ravindar and R.M. Veerappan. MGR’s relationship with his prominent muse, later to become his political mentee, Jayalalitha Jayaram (1948-2016) is well covered. However, coverage on MGR’s relationship with three other movie muses namely B. Saroja Devi, Manjula and Latha is rather inadequate! Furthermore, the relationship MGR had with another talented movie heroine P. Bhanumathi is passingly mentioned. But, missing are descriptions to other front ranking heroines (such as Anjali Devi, Padmini, Savitri and K.R. Vijaya) of MGR, who acted with him in at least three movies. Curiously, Padmini receives a passing mention in a single sentence, “Padmini sells meals to the rickshawmen” with reference to the hit movie Rickshawkaran (1972) for which MGR was awarded the Bharat Award for Best Actor. But, in this movie, Padmini was not paired with MGR. Palaniyaandi Neelakantan (1916-1992), who directed MGR in most number of movies and was associated with creating the MGR’s ‘movie persona’ also fails to receive any mention in the book.

MGR’s greeting message to Tamil Nadu voters June 30, 1977

MGR movie persona

Why I focus on these omissions? MGR was a creator of an ‘unusual movie persona’ that couldn’t be reproduced by any actor in India or anywhere else in Asia until now. He conquered the political world with this movie persona. Some of his contemporaries in India and Sri Lanka, such as Sivaji Ganesan (1928-2001), N.T. Rama Rao (1923-1996), Gamini Fonseka (1936-2004), Amitabh Bachchan (b. 1942), Vijaya Kumaratunga (1945-1988), and Vijayakanth (aka Vijayraj Azhagarswami Naidu, b. 1952) followed his path. But, they flopped miserably. Among this lot, only N.T. Rama Rao was able to succeed in becoming the Chief Minister of Telugu Pradesh state. It should be noted that MGR was not an exception in creating such a movie persona. Few of MGR’s Hollywood contemporaries, like John Wayne and Clint Eastwood, did create similar movie persona as well. But, they couldn’t transform this movie persona into political success.

In politics, MGR was NOT a creator, though he pouted his pet peeves like Annaism. Thus, to comprehend MGR’s grand success as a creator, one needs to study in depth, the hidden hands who deserve credit for molding this MGR’s ‘movie persona’: His script writers (including Karunanidhi, poet Kannadasan, Arurdhas), his lyricists (many, including Tanjai Ramaiah Das, A. Maruthakasi, Pattukottai Kalyanasundaram, Kannadasan, Vaali, Alangudi Somu, Pulamaipithan, Muthukoothan, Muthulingam), his playback singers (many, including Chidambaram Jayaraman, A.M. Rajah, Sirkazhi Govindarajan, T.M. Soundararajan, S.P. Balasubramaniam, K.J. Jesudas), his favorite music directors (S.M. Subbiah Naidu, K.V. Mahadevan, M.S. Viswanathan – T.K. Ramamurthy), his movie directors (P. Neelakantan, M.A. Thirumugam, R. Ramanna) and last but not the least, movie producers (Sandow M.M.A. Sinnappah Thevar, R. Ramanna, G.N. Velumani, R.M. Veerappan) who were loyal to him.

Acting (especially cinema acting) is a life-threatening profession, akin to serving in the military. If one is lucky and opts to play the hero’s role, and choose an ‘action’ route for projecting heroism, he has to take numerous risks. These include, (1) deciding to perform the stunt role by himself or use a ‘double’ which could hurt his hero image, (2) keeping one’s body trim and fit, even after reaching the age when athletes have to retire, (3) to submit oneself to director’s whims for a ‘perfect shoot’ by repeating the action for many ‘takes’, and (4) indulging in on-screen smoking, alcohol and drug use to fit the plot of the movie and the character, even if he is a non-smoker and teetotaler.

Here is a short paragraph by David Thomson, a Hollywood historian, about how MGR’s contemporaries fared in Hollywood. “Bogart, died in 1957, Ronald Colman in 1958, Tyrone Power in 1958, struck down on the set of Solomon and Sheba, Errol Flynn in 1959, Clark Gable in 1960 (soon after the strain of The Misfits), Gary Cooper in 1961, Charles Laughton in 1962. Not one of those men had made it to seventy. Thus every departure seemed premature and shocking, as well as an early warning of what smoking could do to you. On-screen, smoking had stayed heavenly; but the real bodies that carried the message were poisoned.”

That MGR (1917-1987), the foremost popular movie star of his era in South India, lived to reach the Biblical span of 70 years has to be considered as a miracle. His self-restraint and conviction in not indulging in vices like on-screen smoking and alcohol use, at the cost of sacrificing the character range he could play, served him well to reach 70 years. Nevertheless, that his Tamil Nadu contemporaries in politics such as C. Rajagopalachari (aka Rajaji, 1878-1972), E.V. Ramasamy (aka Periyar, 1879-1973), C. Subramaniam (1910-2000), R. Venkataraman (1910-2009), K. Anbazhagan (b. 1922) and M. Karunanidhi (aka Kalaignar, b. 1924) had lived over 90 years makes one feel that MGR’s death at age 70 was rather premature. Had he lived for another 20 years, how much one could have expected from his second career as a leading politician of South India? Some Eelam Tamils do carry a perception that separate Eelam might have come into existence due to the excellent rapport he had with LTTE’s leader V. Prabhakaran.

To reconstruct MGR’s political career, author had taken the trouble to interview quite a number of still living members of MGR’s three Cabinets. These include, R.M. Veerappan (b.1926), Dr. H.V. Hande (b. 1927), Panrutti S. Ramachandran (b. 1937), C. Aranganayagam, C. Ponnaiyan (b. 1942) and Su. Thirunavukkarasar (b. 1949). Other interviewees include, Sa. Ganesan (b. 1930), DK party leader K. Veeramani (b. 1933), script writer Arurdhas (b. 1931), Pulavar Pulamaipithan (b. 1935), and P. H. Pandian (b. 1945). As indicated by their birth years within parenthesis, many had passed 70s. As such, Kannan’s efforts in contacting these folks who had known MGR personally for their perspectives, deserves credit.

MGR was sworn in as the Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu on June 30, 1977. Nearby, I provide a scan of MGR’s greeting message to the voters and public of Tamil Nadu, signed on this day. This appeared in the Ananda Vikatan magazine. In this message, he mentions only the names of three of his predecessors, namely Omanthur Ramaswamy Reddy (1947-1949), Rajaji (1937-1939 and 1952-1954) and his mentor Annadurai (1967-1969). Notably, he had omitted two other predecessors, K. Kamaraj (1954-1963) and M. Karunanidhi (1969-1976).

Kannan also had made use of the revelations from WikiLeaks cables of mid 1970 period, on how the US Consulate in Madras had viewed the political situation from their ‘tinted’ and myopic perspectives. How much authenticity and veracity (other than serving the interests of the spooks of Uncle Sam) exists on these anonymous WikiLeaks cables is anybody’s question.

While paying compliments to MGR’s humanism, and his ‘best relationship with the Centre, especially the prime minister’ during his ten year tenure as the Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu, Kannan also faults MGR’s policies for (1) laying ‘foundations for Tamil Nadu turning into a welfare and freebie state’, (2) fueling ‘corruption and mediocrity’, (3) running an administration that was ‘woven around him and centered on him, (4) a faulty rural vision which ‘held back Tamil Nadu’s industrial growth and infrastructural development’. My opinion is that Kannan’s criticism on ‘corruption and mediocrity’ status of Tamil Nadu during 1977-1987 deserves comparative perspectives. Corruption in Indian politics and Indian society at large have to be studied at intra-state level, regional level and national level.

Corruption in Indian Politics

According to the Corruption Perceptions Index of 2014, by Transparency International, India ranks 85, with a score of only 38. For comparison, the best country (with minimal corruption) is Denmark with rank 1, and a score of 92. The worst country (with maximal corruption) is Somalia with rank 174 and a score of 8. Thus, it is imperative that corruption in India has to be viewed from the national level. Political corruption and kickbacks had existed during the prime ministership of Jawaharlal Nehru (Indian Finance Minister T.T. Krishnamachari’s Haridas Mundhra scandal, exposed by Nehru’s son in law Firoze Gandhi in 1958), Indira Gandhi’s tenure (too numerous to record, especially Nagarwalla scandal, Sanjay Gandhi’s Maruti car scandal) and Rajiv Gandhi’s tenure (especially, Bofors scandal). At the regional level, how did his contemporaries fared during the period MGR was the Chief Minister (CM) of Tamil Nadu? Andhra Pradesh had 7 CMs, namely Jalagam Vengala Rao, Marri Chenna Reddy, Tanguturi Anjaiah, Bhavanam Venkatarami Reddy, Kotia Vijaya Bhaskara Reddy, N.T. Rama Rao and Nedendia Bhaskara Rao. Karnataka state had 3 CMs, namely Devaraj Urs, R. Gundu Rao and Ramakrishna Hegde. Kerala state had 4 CMs, namely A.K. Anthony, P.K. Vasudevan Nair, C.H. Mohamed Koya, E.K. Nayanar and K Karunakaran. While some of these CMs belonged to the Congress Party, led by Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi, others represented other national and regional parties. Then, at the intra-state level, it would have been a good exercise, if Kannan had compared MGR’s 10 year tenure (3,624 days) as CM, to that of his predecessors Karunanidhi’s multiple tenures of 6,858 days (between 1969 and 2011) and K. Kamaraj’s nearly 10 year tenure 3,432 days, for corruption and mediocrity status.

Recently, I located an interesting quote by Palaniappan Chidambaram (b. 1945) in India Today (April 23, 2001), cited in a 2007 research paper by Jyoti Khanna and Michael Johnston entitled, ‘India’s middlemen: Connecting by corrupting?’. Chidambaram had stated, “Corruption in India is a long running epic and there is no end in sight. Many characters have played their part and departed, some hold center-stage today and many are waiting in the wings to enter or re-enter the stage.” This scion (grandson of Sir Annamalai Chettiar) of one of the most influential moneybags of Tamil Nadu should know, because he was an eye witness to corruptions in the Congress Party regimes of Indira Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi, Narasimha Rao and Man Mohan Singh.

Sour-Grapes Sentiments of Communists

A word of derision on the Communist Party politicians [both, Community Party of India (CPI) and Communist Party of India (Marxist)- CPI(M)] and their fellow travelers like journalist Narasimhan Ram (b.1945), talented Tamil writer Dandapani Jayakanthan (1934-2015) and academic M.S.S.Pandian) of Tamil Nadu is in order. Jayakanthan and Ram also turned out to be political chameleons and hypocrites. Here and there, Kannan had highlighted the criticism of these folks on MGR’s career and policies. I, for one, believe that with his acumen and humoring instinct, MGR kept these folks on tenterhooks, knowing well that these flag wavers for Communism could never carry the mass support he enjoyed. I have nothing but scorn for Jayakanthan, whose portrayal of a woman MGR fan in one of his short story, Cinemavukku Pona Sithalu (1972) was of mean taste. That he also dabbled in Tamil cinema and politics on his own, but failed miserably indicates that Jayakanthan simply suffered from ‘sour grapes sentiments’. In addition, Jayakanthan and his fellow travelers of Communist path completely ignore the fact that celebrity worship of their own category (Lenin, Stalin, Mao, Fidel and Che) was also practiced in India and elsewhere disregarding the reality that their own celebrities were power-grapping maniacs who did kill thousands to entrench themselves in political power in the name of Communism.

Income Tax Issues of Indian Actors

Another theme which I wish to comment relates to the income tax issues and ‘black money’ payments of MGR. Akin to the corruption issue, here also, MGR’s case deserve comparison to that of his equally talented movie contemporaries of his era. A news time that appeared in the Hindu (Madras) of March 27, 1982, had the caption, ‘Hema Malini tops in income-tax arrears’. She had to pay 18.11 lakhs rupees. Then the second in the list was Raj Kapoor who owed 17.34 lakhs rupees. MGR was third, with 9.27 lakhs rupees. M.R. Radha (who had died in 1979) owed 8.52 lakhs rupees. Other South Indian actors included in this list were, Savitri (who had died in 1981, 6.93 lakhs rupees), A. Nageswara Rao (6.12 lakhs rupees), Jamuna (5.79 lakhs rupees), Vijayanirmala (3.98 lakhs rupees), Sivaji Ganesan (3.78 lakhs rupees) and N.T. Rama Rao (2.39 lakhs rupees). I would have wished if Kannan with his law degree background could have enlightened the readers more on this perennial issue with his own perspectives.

Madurai 1981 Tamil Conference gift plaque

Madurai International Tamil Conference of 1981

The Fifth International Tamil Conference was held in Madurai in January 1981. It receives mention in two pages of the book. This particular conference was postponed twice. It was originally scheduled to be held in January 1980, and subsequently in June 1980. Kannan indicates that ‘The MGR government spent 10 crore rupees on the show.” As a Sri Lankan delegate to this Conference, who was present at the venue, and who was given an opportunity to read a research paper on Saint Arunagirinathar (That specific session was chaired by musician-musicologist Dr. S. Ramanathan), I have a different impression to that offered by the author. My paper was one of the 197 papers presented at this conference. Kannan states, “The DMK boycotted the conference. Kalaignar [Karunanidhi] wrote that they were not invited properly…” What I heard in the streets of Madurai then was this wise quip: “This Karunanidhi guy shouts from the roof top, about his passion for Tamil. If he has an iota of sincerity in what he screams about, he can easily come to Madurai from Madras, despite finagling about proper invitations. We see here, so many other delegates who had come from other countries to pay homage to Mother Tamil. Karunanidhi is a good for nothing guy! He simply plays politics.” All delegates were given a round metallic memorial plaque as a gift. I still keep it, though it had lost its sheen due to improper storage conditions in Sri Lanka and transfer from place to place during the Civil War period. Nearby, I provide a photo of this metallic memorial plaque. One can read the inscriptions in Tamil (in red), in the inner circle of rings. Inscription in the upper half reads ‘Aintham Ulahath Thamizh MaaNadu Madurai 1981’ (Fifth International Tamil Conference, Madurai, 1981). Lower half inscription reads ‘Tamil Nadu Arasu Anballippu’ (Gift of Tamil Nadu Government). In the center is the insignia of the image of Madurai Meenakshi Temple’s Gopuram [Gateway Tower], with the holy book Tirukurral at the base. When I look at this gift, it reminds me of my first foreign trip from Sri Lanka as well as the opportunity of 5 second handshake I had with MGR at the Conference venue.

The University of Chicago academic, Norman Cutler, as an eye-witness to this conference, opined as follows: “MGR deserves credit for playing his cards well. Indira Gandhi was not eager to show too much enthusiasm for the Tamil conference…But, Mrs. Gandhi also knew that she could not ignore the conference altogether without provoking the ire of the Tamil populace. She therefore was compelled to give in at least a little to MGR’s stratagem and show herself to the Madurai crowd.” After all, Indira Gandhi was first and foremost a politician!

MGR – a Tamilian or Malayalee?

Was MGR a Tamilian or a Keralite (Malayalee)? MGR’s pals turned foes in DMK party (Karunanidhi and Kannadasan in particular) exposed their mean-minded nastiness, only when they fell out with him. For this sort of Tamil jingoism, Tamil Nadu commoners paid back by re-electing MGR as the Chief Minister repeatedly. For Tamil Nadu folks, MGR was one of them, because he had lived only among the Tamils in Ceylon and Tamil Nadu, though his parents were from Kerala. Thus, it is a bit jarring to me, when I read that “MGR was originally from Kerala” in the Notes section (p. 397) of the book. For comparison, allow me to cite the ancestry of MGR’s legendary contemporary and centenarian actor Kirk Douglas (b. 1916), who was born merely five weeks before MGR in Amsterdam, New York. It is true that his parents emigrated to USA from the old Russian empire. Does that make Kirk Douglas, a Russian? Kirk Douglas was born in USA and is an American. In reality, his ‘mother tongue’ is English, though he was spoken in Yiddish by his English-illiterate parents, when he was young.

MGR’s relationship with Prabhakaran

Kannan’s view on MGR’s relationship with Prabhakaran is, “while cultivating and funding the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam’s V. Prabhakaran, he also helped balance the DMK’s shrill demands. However, his influence over Prabhakaran was greatly overrated.” It could be so, but available evidences are against this inference. There is no doubt that among all the Indian politicians who held power, it was only MGR who helped the Liberation Tigers liberally and sincerely. Because of this help, Prabhakaran came to trust MGR and none of the others (prime ministers from Indira Gandhi to Man Mohan Singh, and Tamil Nadu chief ministers Karunanidhi and Jayalalitha). As I have indicated previously in my writings, only MGR had the Pirantha Mann Patru (i.e., birth soil bond) with Sri Lanka and influencing the events of the land of his birth within his reach, became one of his missions, when he realized that his life is nearing the end. His unpredictable deeds, in the last 3 years of his life, always favoring LTTE had to be viewed with his penchant for not allowing anyone to steal a scene from him (a skill he had sharpened in his acting career as a hero, and used elegantly in his political career too). Biography of his bogeyman, Mohandas provides quite a few episodes along this line of thought.

Here is a revealing thought by Mohandas: “MGR was gradually getting in touch with the [Tamil] militant groups – particularly the LTTE, through sources other than the CID. His idea seemed to be to impress on the Central Government his hold over the militant groups and use it as a card to be used if and when the need arose. This was a dangerous game, but as MGR once told me, life was not work it without risks.” Why MGR played this game? It is my guess, that he had come to resent the RAW gumshoes and diplomats (like J.N. Dixit) from the Central Government dictating terms to him within Tamil Nadu territory, which he considered as his own parish. Even none other than Dixit had recorded MGR’s deeds of favoring LTTE as, “Despite having supported Rajiv Gandhi in signing the Indo-Sri Lanka Agreement, he [MGR] remained committed to assisting the LTTE. This inclination of MGR was so fundamental that he continued to provide finances and logistical facilities to Prabhakaran even after the IPKF launched operations against the LTTE.”

Coda

There exists some slips in facts and contexts which deserve correction, when the next edition of this worthy book is prepared. I’ll point these out to the author privately. In conclusion, Kannan deserves all the praise for his attentiveness to details in MGR’s political career (from 1969 to 1987, chapters 5 to 8) and bringing out this excellent biography. Nevertheless, it’s my contention that as an exceptionally charismatic leader, MGR’s dual career in cinema and politics still holds many mysteries and Kannan had provided the best opening gambit for serious MGR scholarship for others to follow. These mysteries lay hidden in MGR’s personal/private documents (such as diaries, note books and letters he wrote to his confidants and family members). If these documents become available in the future, MGR’s fans will be more delighted.

Cited Sources

Anonymous: Hema Malini tops in income-tax arrears. The Hindu (Madras), March 27, 1982, p.6.

Norman Cutler: The Fish-eyed Goddess meets the Movie star: An eyewitness account of the Fifth International Tamil Conference. Pacific Affairs, 1983; vol.56, pp. 270-277.

J.N. Dixit: Assignment Colombo, Vijita Yapa bookshop, Colombo, 1998.

Frederick Elkin: Popular hero symbols and audience gratifications. Journal of Educational Sociology, 1955; vol. 29, pp. 97-107.

Kavignar Kannadasan: Manavaasam, Vanathi Pathippagam, Chennai, 5th edition, 1991 (originally published in 1988).

Jyoti Khanna and Michael Johnston: India’s middlemen: Connecting by corrupting?’ Crime Law Social Change, 2007; vol.48, pp. 151-168.

- Mohandas: MGR – The Man and the Myth, Panther Publishers, Bangalore, 1992.

David Thomson: The Whole Equation – A History of Hollywood, Alfred Knopf, New York, 2004.

Correction by Sachi: I wish to mention and correct a typo slip, in the quote attributed to MGR, in the section ‘MGR’s relationship with Prabhakaran’. Mohandas had mentioned what MGR told him as follows: ‘Life was not WORTH without risks’. The word ‘work’ has to be replaced with ‘worth’. The error is regretted.

The review brings back my memories of Madurai International Tamil Conference of 1981. I was a student volunteer and I completely echo Dr. Sachi’s version of public views of Karunanidhi’s attitude.

Dr. Sachi clarifies MGR’s relationship with Prabhakaran to set the records straight.