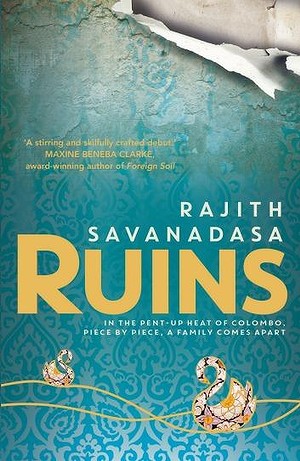

Rajith Savanadasa: A little bit of him in each of his characters. Photo: Pat Scala

by Jane Sullivan, ‘Sydney Morning Herald, July 9, 2016

Rajith Savanadasa had written a few drafts of his first novel, and it wasn’t working. It was supposed to be a big novel about a Sri Lankan family that also commented on the country, culture and politics and the civil war that had raged for 25 years and had cost the lives of an estimated 100,000 people.

But the Melbourne-based writer had trouble figuring out how to integrate the family and the bigger picture. “It got terribly contrived,” he says. “I was making my characters do things that would get the message across.”

He almost gave up. But then he began voluntary work with a group of asylum seekers in Darebin, interviewing them and recording their stories on a website, Open City Stories. “I’d be drawn into the story and I’d be moved. And I thought: These people are not really talking about the politics, they are just telling me their stories about what it was like to live in Iran or Bangladesh.

“That made me think I had to forget about the idea of a message. I should just tell the story.”

“That made me think I had to forget about the idea of a message. I should just tell the story.”

He tells five intertwining stories in Ruins, a tale of a middle-class family in Colombo at the time the war was coming to an end. There’s Mano, the editor of a local newspaper; his unhappy wife Lakshmi; their hustling son Niranjan; their Iron Maiden fan daughter Anoushka; and their humble servant Latha, who quietly runs the household.

At first glance, the war seems far away, and the novel seems all about internal tensions in the family. But outside pressures intrude: an air raid, media censorship, road blocks, a missing boy, a dead soldier, Lakshmi’s Tamil identity in a Sinhalese community – and an isolated but shocking moment of intimidating violence when a government minister visits Mano’s office and casually smashes a picture of his family.

“If I wrote the things that actually happened, you wouldn’t believe it,” Savanadasa says of his restrained portrayal. “One minister’s kids were disciplined by a school teacher: he tied the teacher to a tree and had him flogged. The government at that time had so much power. They won the war and they had so much support from the Sinhalese majority. They acted on impulse and they got away with it.”

What happened at the end of the war is still contested, with accusations of war crimes on both sides. In the final offensive in 2009, hundreds of thousands of civilians were trapped on a narrow strip of beach between the two armies. The UN estimates that 40,000 of them died before the rebel Tamil Tigers surrendered.

In Ruins, these battles are vague rumours, while everyone rejoices at the Government victory over the “terrorists”. As Anoushka says of the air raid, “someone was probably going to die, but it was never anyone we knew”. It was all part of the culture of oppression, Savanadasa says, which is why his characters turn a blind eye to what is going on. “You don’t talk about things that challenge the status quo. You don’t talk about anything too personal. You don’t present as vulnerable at all.

“Politics is a separate thing: That’s just the politicians, they’re not like us. Or, that’s just happening in the north, we have nothing to do with it. I feel we do have to take some level of responsibility for what’s happened – and what is still happening.”

Like most middle-class Sinhalese children in Colombo, Savanadasa grew up insulated from the conflict. His father was “something like an economist”, head of the national chamber of commerce; his mother was a director of the tourist board, and still works as a teacher. They encouraged him to read, and he discovered everything from Frederick Forsyth thrillers to Somerset Maugham and Arthur C. Clarke in his father’s home library.

But writing was another matter. “Even now my mother says, ‘It’s a great hobby, but you have got a proper job?’ ” He never wrote anything except school essays, and it never occurred to him that he might become a writer; the choice was to study to become either a doctor or an engineer. After high school, he came to Melbourne in 2001 at the age of 20 to study engineering at RMIT.

It was a culture shock. “You lose your sense of self to a degree. Everyone around you doesn’t recognise you, everything you have achieved doesn’t matter. And there were two or three phases when everything I built up was taken away and I had to start again.”

Savanadasa struggled with a recurring sports knee injury that needed surgery. Although his parents gave him what they could, money was short and he had to support himself with part-time jobs. He had trouble with a room mate. He failed a few subjects. But in the end he got his degree.

At the same time, he discovered writing. He took up creative writing as an elective subject in his final year, then got a job and went on to take RMIT’s Professional Writing and Editing course. At first he didn’t know what to write about, and he imitated the styles of everything he was reading: magic realism, science fiction, playful postmodernism. His influences included Salman Rushdie, Rohinton Mistry and Junot Diaz, “and I had a very big David Foster Wallace phase”.

He began to get noticed. In 2013 he was shortlisted for the Asia-Europe Foundation short-story prize and the Fish Publishing short-story prize. The following year he received a Wheeler Centre Hotdesk Fellowship and a place in the manuscript-development program run by Queensland Writers Centre and Hachette, which led to his debut.

It’s not his own family in the book, he says. But there is a little bit of him in each character. Perhaps as a teenager he was most like Anoushka, in rebellion against her strict upbringing, a lonely misfit with unrequited crushes on girlfriends. “I had to sneak out to parties, I had crushes on girls. My parents always said ‘You have to think of the future, you have got to study, you can think about relationships and sex later on’. But you’re in your teens and you’re going crazy.”

He has dedicated the book to Yasa, the family servant, who has much in common with his character Latha. She grew up in a poor village thinking her father was dead, only to meet him many years later and discover he had rejected her as a child. In the meantime she was brought to Colombo and worked as a servant for the Savanadasa family.

Young Rajith grew up with her. “She was a bit younger than my mum, like a great friend, but not an equal. That was something I thought of after I’d been here for a while. She sacrificed everything and we still treated her terribly. The worst part was we didn’t think we were treating her terribly, we thought we’d done her a favour.”

After 15 years, Savanadasa is settled in Melbourne. He is married to the writer Melanie Joosten, they have a nine-month-old daughter, Mala, and he works as a copywriter with Telstra. He still frequently visits his family in Sri Lanka, where Ruins will also be published. His mother liked the book, though she worried people might think that she didn’t look after her children properly. “Dad read about half and said ‘It’s very engaging and modern’. Then I noticed he picked up The Revenant and started reading that.”

He has signed a contract for a second novel, set in Melbourne. It’s about an asylum seeker who has to prove he is afraid to go back to Sri Lanka. “How do you prove to someone you’re afraid? And a person may not know it. He has to prove both to himself and to the authorities that he’s fearful for his life.”

While reluctant to comment on border-protection policy, Savanadasa doesn’t see why asylum seekers can’t be processed onshore. And he’s acutely aware how close their experience is to his own.

“It’s quite scary thinking it could have been me if my situation had been dangerous. I could have come here in a boat.”

Ruins is published by Hachette at $27.99.