Even though he is in London, thousands of miles away from the barren prison cell in Sri Lanka where he was raped several years ago, Raj is still thrown headlong into searing memories. One of the actors reads the words Raj—whose real name has been changed—has spoken:

For many months I was kept in the same cell. No bed. No windows. Only one sheet, no pillows. I always remained in a corner of the room. I was in constant fear that anything could happen at any time. I don’t like to remember it.… I was praying and calling my mother’s name all the time.

Try Newsweek Print + Digital for only $1.25 per week

The closeness of the action and the words in the play to his own experience are too much for Raj to bear. He can hardly speak and breaks into tears. At one point, he left the Excel Conference Center, where the play was being mounted, and walked along the river Thames to regain his composure.

“I have lost my dignity. I have lost my dignity,” he says later, choking and gasping just to get the words out. “How will I ever get it back?”

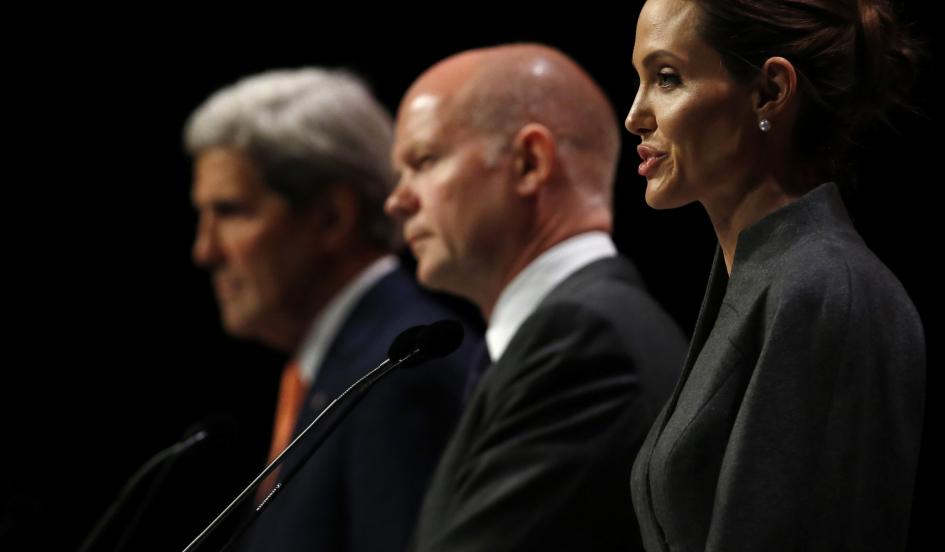

Even seeing photographs of wartime victims on the walls of the hall, where actress Angelina Jolie and British foreign secretary William Hague are hosting the Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict, is too much for Raj to endure.

The aim of the four-day summit—which has brought together an eclectic mix of politicians and celebrities to London’s Docklands—is to get states to sign up to an international code of conduct that will make it tougher for perpetrators of violent crimes to go free.

Strutting through the crowd on towering high heels was the human rights lawyer, Amal Almuddin, who is about to marry George Clooney. There was also the designer Stella McCartney in a sharp white suit, which matched Jolie’s pristine wardrobe. There was Bianca Jagger and foreign ministers like Secretary of State John Kerry, United Nations heavy hitters like its resident expert on sexual violence in conflict like Zainab Hawa Bangura, as well as the woman who runs the U.N. mission in South Sudan, Hilde Johnson.

And there were many victims of sexual violence, like Raj.

“War zone rape thrives on silence,” Jolie said in her opening remarks, and Hague agrees: Sexual crimes should not be shameful. “It’s about waking people up,” he told Newsweek. “Despite all the communications within the modern age, these crimes have taken place on a vast scale without the world noticing. And that now is changing.”

Raj’s story, while painful, is not uncommon in Sri Lanka. Government forces there accused him of being a Tamil Tiger, an armed secessionist group that waged war against the Sri Lankan government between 1983 and 2009, but he says he never held a gun and was never a member. “I don’t like violence,” he insists.

According to human rights lawyers and activists at the conference, the post-conflict situation in Sri Lanka is dire. The country is ruled by a dynasty—that of President Mahinda Rakapaksa and his family—and judicial and legislative impunity has become even worse since the war ended.

Five years after the Sri Lankan government defeated the Tamil Tigers, human rights groups report continued abductions, torture, rapes and other sexual violence against both men and women of the Tamil minority.

“For all intents and purposes, the war has not finished,” insists Frances Harrison, author of Still Counting the Dead, a brutal account of the Sri Lankan conflict. “Especially for young men and women who had association with the rebels, they are still being abducted, hunted down. It’s a mopping up operation five years on.”

Harrison says the Sri Lankan government—which is not considered a pariah state, despite its persistent human rights violations—“are using very sophisticated intelligence methods like facial-recognition software, as well as hooded informers who nod when they identify somebody.”

Unlike victims of the conflicts in Somalia, the Balkans, South Africa, Syria and Afghanistan—all of which are represented at the conference—Tamil activists have struggled to get a voice.

When considering rape during wartime, “I have always had to compare Sri Lanka to Congo and Bosnia,” says Nimmi Gowrinathan, a Sri Lankan–American from the Center for Conflict Negotiation and Recovery. “Why has [the Sri Lankan misery] not been reported? It’s more of a hidden war. I think governments like the U.K. and U.S. still want to do business with them.”

A report this year by Yasmin Sooka—a member of the Bar Human Rights Committee of England and Wales, who has worked in Sierra Leone and Rwanda—found that “abduction, arbitrary detention, torture, rape and sexual violence [in Sri Lanka] have increased in the postwar period.”

And Desmond Tutu, the South African archbishop emeritus, wrote in the introduction to Sooka’s report: “I find it horrifying that almost half the witnesses interviewed for this report attempted to kill themselves after reaching safety outside Sri Lanka.”

Raj is one of those. He has tried to commit suicide twice since he arrived in the U.K., where he has also been detained, pending deportation, for a visa violation. He still has strong memories of those dark and lonely days in his Sri Lankan cell.

“They pushed me to the floor, they stripped me, they held my head and suffocated me, then they did bad, bad things to me,” he said, describing how he was raped. “I was so very far from home.… I was so far away. When I think about it, I can’t breathe.”

In one of the many conference fringe events, the rapper, Mathangi Arulpragasam—better known as M.I.A.—could also barely control her emotions. Standing on a small stage at the Canadian Embassy in London, dressed in bright green silk, the 38-year-old Sri Lankan–British singer—famous for dancing hugely pregnant at the Grammy Awards on the night her baby was due—read out loud a gruesome account of another gang rape in Sri Lanka.

“You can’t take me, I have a child,” M.I.A. read, her hands shaking. “But that did not get me anywhere.… I was terrified, thinking now it was my time to be tortured, abducted and killed.”

Next up was Bianca Jagger, limping slightly from back pain and using a cane, who broke down in tears as she read white-faced another firsthand account of being raped.

“To torture and rape someone is the most destructive thing,” says Harrison, who has interviewed dozens of Sri Lankan rape victims. “It is like sending someone outdoors naked.”

The numbers of victims of Sri Lanka’s quarter of a century of conflict are hard to pin down. The U.N. estimates 40,000 civilians killed, but Harrison says the true figure may be double that. No one can put a figure on the number of rape victims.

“It is believed the number of men and women raped during the war is in the thousands, but I think that most raped occurred post-conflict,” said Gowrinathan. The crimes were used, she says, “as a victory thing, to show who won the war.”

In the government forces’ post-conflict dragnet to capture former Tiger fighters and supporters, hundreds of Tamils were unfairly identified by informers—then brutally raped.

Rajini, 28, is one of those victims. She did work for the Tigers, but as a messenger during the war, passing parcels and letters. She stopped working for them in 2009, when the war was ending, and she became concerned for herself and her family. She moved to the north of Sri Lanka and tried to rebuild her life after the war. But she lived in constant fear. She says she always felt that the moment was coming when she would be caught.

One day, last year, she was. At dusk, a plain white van, so feared by Tamil civilians, followed her home from work. Men got out and asked to see her ID card. She was taken away for questioning. She was blindfolded, stripped, tied up, beaten, tortured by having a polythene bag that once held petrol tied over her head, burned by cigarettes on her genitals and breasts and elsewhere, then beaten with a plastic hose filled with sand.

Her tiny, slender body was held upside down. She was hung by her feet. Her head was plunged in buckets of water. This torture went on for days.

Then she was raped, several times a day, by several men. That torture went on for weeks.

Like Raj, her family bribed officials to get her out of jail before she was killed. After weeks of holding out, she had signed a false confession. Even after she signed it, they continued to rape her.

“They use the cigarette burns as a kind of branding,” says Harrison. “Some victims, especially women, have up to 30 on their body—so that if they are picked up again, they can be identified as someone who had been jailed.… They do it on parts of their body not covered by their saris so they are forever marked—forever victims.”

When Rajina was freed she was smuggled by fishing boat to India, then to the U.K. But, like Raj, the memories are never far from her mind. So far in Sri Lanka, no one has been held accountable for the post-conflict crimes. If Jolie and Hague’s international protocol is made effective, the men who raped Raj and Rajina would not have walked free.

“There is a pattern in the way people are abducted, tortured, raped, then released for money,” says Harrison. “Their stories are chillingly similar. There are different wings of the [Sri Lankan] security forces—navy, army, different bits of the police—collaborating to do this. It is systematic, organized. It is not about running amok. It is not opportunistic rape.”

“Even when I told them what they wanted to hear,” says Raj, who was forced to confess to a crime he did not commit, “they continued to hurt me.… My God…I screamed and screamed.… It did nothing.”

Jolie will only feel her work is done “when I see evidence being collected in court. When we have seen that regularly, we will know there will have been a change. These things happen because these people are sure they can get away with it.”

“It’s vital to continue [the effort to end rape in war],” says Hague, a biographer of English slavery abolitionist William Wilberforce. When talking about sexual violence in conflicts, Hague is fond of quoting Wilberforce: “You may choose to look the other way, but you can never say you did not know.”

That, Jolie insists, is the point of being in the public eye. Hague agrees. “What would be the point of being involved in public life and choosing not to do something about a crime as serious as rape?” said Hague.

http://www.newsweek.com/celebrities-join-fight-stop-rape-weapon-war-255054?piano_t=1