by Mini Krishnan, ‘The Hindu,’ Chennai, May 12, 2016

A powerful translatorial voice has fallen silent. Once in a long while, we encounter a writer who really changed the literary landscape he or she inhabited. While U.R. Ananthamurthy, Ismat Chughtai, Sarah Joseph, Nirmal Verma and Indira Goswami might be cited, I think we can safely say that one who makes such writers available to a population which cannot read them in their original languages is equally a force of Literature, of Nature even.

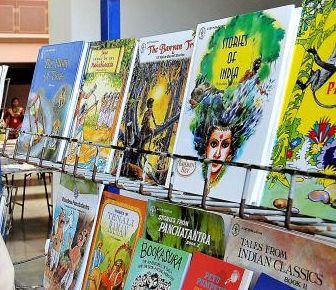

An academic and a literary critic, Lakshmi Holmstrom entered publishing with one of the best-selling anthologies of all time: The Inner Courtyard: Stories by Indian Women (1990), a commission she received from Virago when she wrote a letter pointing out certain cultural opacities and misunderstandings in one of their publications pertaining to India. Thereafter, she almost single-handedly benchmarked forever the quality and tenor of English translations of contemporary Tamil writers. Imagine your bookshelf without Ambai, Na. Muthuswamy, Ashokamitran, Sundara Ramaswamy, Madhavaiah, Bama, Imayam, Cheran and Salma. Holmstrom made sure that they became part of our lives. Her huge corpus also included Silappadikaram Manimekalai, two of the five great epics of classical Tamil.

Influencing a whole generation

The soft voice and gentle, almost self-deprecatory, smile belied the steely quality of her spirit which her publishers sensed when she turned in first-rate scripts, kept deadlines, and literally influenced a whole generation of readers who were introduced to some of the most significant Tamil writers of times past and present. She moved with equal ease from “Halva nestling upon a banana leaf glistening with ghee” to “She gathered up any rice and coins left upon the corpse, and tied them all up at her waist” to “They must fry vadais and bhajjis to break their fast; boil some beans for a sundal… there would also be thenonbu kanji.” She entered not only the literary texts she selected for translation, but the cultural establishments that produced them.

I worked with her on three books, two of which won national awards for translation (Bama’s Karukkuand Ambai’s In a Forest, a Deer). The third, Bama’s Sangati, though ignored by juries, reprints every year. Yet not once did she argue boastfully or write angry put-downers. Not even when she was disappointed. At seminars and literary meetings, she was cooperative and contributory. Even when someone disagreed sharply, as did a young participant in the University of Hyderabad in January 2011, she took it gracefully and with strength, when she might have snubbed him on the spot with a quick phone call to Sukirtharani, the poet he had accused her of mistranslating. There were other more influential detractors who said that the time and distance she spent away from Tamil Nadu enfeebled her cultural understanding but could so many juries have been wrong? The Crossword Award in 2000, 2006, 2015 and the A.K. Ramanujan Prize in 2016, not to mention the Iyal Virudhu Lifetime Achievement Award given by the Canada-based Tamil Literary Garden.

At a Tarjuma festival in Ahmedabad three years ago, as she was presenting Sri Lankan war poetry (Cheran), two scholars seated in the row ahead of me were astounded at what they were listening to. One of them said: “I had no idea there was this kind of writing. Thank God for Lakshmi’s work.”

Beneath the mango tree, where three streets meet,

The bodies lie burning;

The flames rising

blacken the unfurled palm leaves above…

Even the birds have lost their song,

their voices suppressed.

Children forget to scream,

their shocked eyelids frozen.

(with Sascha Ebeling)

Unlike most other translators — narcissistic and unwilling to share — Lakshmi mentored younger translators: Sascha Ebeling, Subashree Krishnaswamy and K. Srilata. She never pontificated patronisingly about translation or took harsh stands. If she disagreed, it was put across in so ladylike a manner that one was hard put to find a counterargument that did not come across as shrill or quarrelsome: “I went for a long walk to think things through and I have to say that I do not agree.”

From friends sharing their grief, I have a forwarded an email her sister Nalini sent saying: “She died in harness, with 30 pages left to edit in Beasts of Burden, due to enter its second edition.”

A forest, a lake, and a purple sea — all in the inner courtyard of a great translator. Here is her voice behind Na. Muthuswamy’s: How many more days were there to amavasai? How many more days for the stars to blossom in the ink black night? In the western heavens, the moon hung like a sliver of pumpkin. How long would it be until amavasai?… The breeze fell upon me, laden with neem.

Mini Krishnan is Consultant, Publishing, Oxford University Press, India.