by Sharanya Manivannan, Medium, November 15, 2020

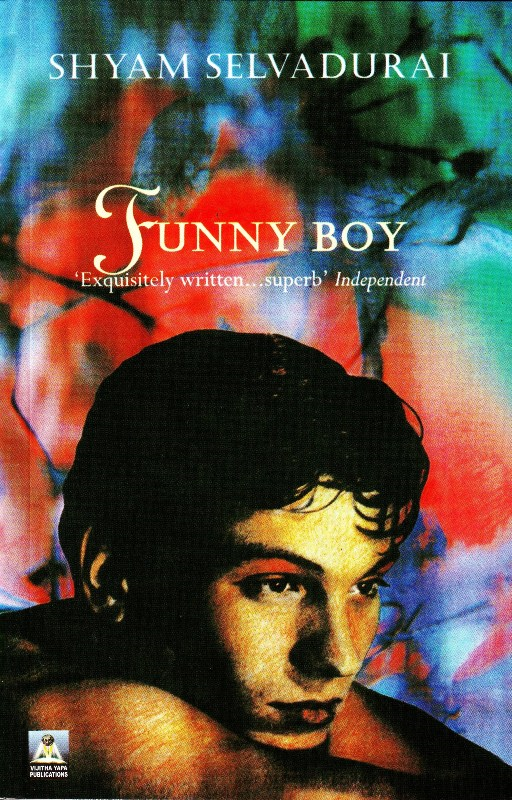

I had first known that there was a film adaptation of Shyam Selvadurai’s iconic novel Funny Boy when I had heard about closed screenings of it in Colombo sometime in mid-2020. The story is a bildungsroman about a queer, upper-class Tamil teenager, culminating in the Black July riots of 1983 that took place across Sri Lanka (Ilankai). Many Tamil families left the island that year, in search of asylum. Some, like the family in the book and novel, boarded flights to the West. Others travelled, sometimes by sea, to India, and then journeyed further or stayed, depending on their resources. 1983 is generally regarded as the official start of Sri Lanka’s civil war. By its official end, in 2009, the chief players were the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and the Sri Lankan army. There were other players along the way, on different sides.

In early November 2020, two trailers were released of the film online and with them came public outcry, primarily from the Ilankai Tamil diaspora, mainly about two issues: firstly, the principal cast contained only one half-Tamil actor, with all the other roles being played by Sinhala actors and others of South Asian backgrounds. Secondly, the clips of spoken Tamil in the film ranged from stilted to atrocious. One clip in particular that made the rounds, of a woman applying makeup on a child, seemed to feature an actor of North Indian descent who had likely been coached in Indian Tamil, and very poorly at that.

I read that Selvadurai had had a hand in both the casting and the script, including recommending the actor who played the role based on himself. That the author had the right to make choices about how his story (both creative, and personal) was reflected onscreen was something that I was respectful of, and Mehta’s oeuvre implied that the project would be in good hands. I especially did not find criticism of class depiction relevant: the book and film are about a particular milieu. But I agreed unequivocally that more Tamils from the island, including from the diaspora, should have been cast, period. Here, class is relevant, as auditions were closed calls, circulated within the same milieu mentioned. I was bothered by the Tamil in the clip, but it did not damper my anticipation of the film.

I read that Selvadurai had had a hand in both the casting and the script, including recommending the actor who played the role based on himself. That the author had the right to make choices about how his story (both creative, and personal) was reflected onscreen was something that I was respectful of, and Mehta’s oeuvre implied that the project would be in good hands. I especially did not find criticism of class depiction relevant: the book and film are about a particular milieu. But I agreed unequivocally that more Tamils from the island, including from the diaspora, should have been cast, period. Here, class is relevant, as auditions were closed calls, circulated within the same milieu mentioned. I was bothered by the Tamil in the clip, but it did not damper my anticipation of the film.

Then, I received a phone call from an Indian Tamil film director whom I had known a long time ago, and had not seen in over half a decade. He was excited to tell me that Deepa Mehta had reached out to one of her Indian collaborators, who had contacted him and delegated to him the task of fixing the Tamil language issues in the film. He was sure I would help him. He set up a private screening for me for the next day, November 7th, at a studio. He said he would not know the scope of the work until I saw the film.

At this juncture, I should say: I am Ilankai Tamil, and I live in Chennai. I was born two years after the Black July riots, and my family left the island in 1990 for Malaysia. I moved to India in 2007, about a year and a half before the official end of the Sri Lankan civil war. My father is Indian Tamil. I do not identify culturally as Chennai Tamil; I was raised entirely in my mother’s Batticaloa-Colombo Tamil culture. I do not necessarily identify with Jaffna Tamilness either, which is the dominant cultural narrative of the Ilankai Tamil diaspora, except where it overlapped with my upbringing in Kuala Lumpur and Pulau Pinang which have long-entrenched Ceylonese communities. (A very quick and pertinent history lesson: “Ceylonese” is the self-identification of Tamils who migrated to Malaya from Ceylon when both were British subjects, and they chose to retain this identification as Malaya became Malaysia with apartheid-style policies. The community preferred to tick “Other” in relevant checkboxes than share the “Indian” checkbox with Tamils from India. Class and caste are both relevant to why, but are not the only factors.).

I have many overlaps in my background. I try to hold wide margins for confusions, longings, unbelongings, mistakes, accents, questions, reckonings, growth and unlearning in people, because I must grant myself that grace and want to be granted it by others too. This brief description of cultural positionality is made here primarily so that the idea of Tamil culture as not being a monolith is asserted.

I prefer the term Ilankai, do not mind at all the term Sri Lanka, and haven’t yet gotten comfortable with the ancient term Eelam because I haven’t shaken off the violence it conjures to me, specifically violence committed by one’s own in the waging of war for a separatist state (but I’m getting there, and I understand and respect why many people choose to use it). I spend time in Sri Lanka when I can, and have created a meaningful relationship with the place as an adult, incorporating but not led by my childhood nostalgia. Not every Ilankai Tamil has this privilege, and not everyone wants it, and it is also something I cannot take for granted as always being possible for me. This is where I am on my journey. I do not speak for anyone else’s.

I have not personally encountered diasporic (from Asia, Europe, North America and Australasia) and non-diasporic Ilankai Tamils who express the kind of profound, blood-rousing, chest-thumping cultural affiliations for Indian Tamils that a disturbing number of Indian Tamils express vice versa. This is not to say they don’t exist. Especially among younger people, who are empowered with attractive new rhetoric on race politics, I am aware that Tamilness as an encompassing identity is a thing. A thing that wipes away the cracks and distinctions between Jaffna and Batticaloa Tamils, between Colombo and Malayaha Tamils (not to be confused with Malaysian Tamils of different origins), between Madurai and Mumbai Tamils, between Florida and Zurich Tamils — a sweet harmony that exists in the head and heart and in music, in ornamentation and, yes, on celluloid. It’s not a shallow feeling in experience, even if it appears to be in observation.

But I live here in Tamil Nadu, and I can speak for how they, Indian Tamils, (don’t) see us here. What I have to say in this piece is not so much about Funny Boy as it is about Indian Tamils and their appropriative relationship to, and unthinking claim over, Ilankai Tamils.

I agreed to watch the film and give my feedback on it because I had been keen on seeing it anyway, and took in good faith that the creators wanted to heal the injury to the Ilankai Tamil communities done through the casting choices.

The private screening in Chennai was held only for me; also present were Mehta’s liaison, two of his assistants, two studio staff and a sound engineer. Very early into the screening, two of the people present had a whispered conversation — “Just tell her [Mehta] to redub the whole film in English”. “She can’t. It was submitted to the Oscars as a Tamil language entry.”

I must, as I write this, pause for a moment because this is a point that still leaves me in shock. How could so little care have been taken about the rendering of the dialogues in not just the official language of the film, but the language of peoples who have endured generations of pain? As Sinthujan Varatharajah, one of the most vocal detractors of this film, has explained in detail on social media, there is a political backdrop in which language is a key component, and this should never have been ignored.

At the screening, the liaison kept looking at me at different points of dialogue and I would nod and say, “That’s right, actually.” He had assumed after his prior viewing that the Tamil was just gibberish. The Tamil he was hearing, spoken by the actors playing Appa and Amma was accented and inconsistent, yes. But it was in dialect. It was not, as he had thought, bad Tamil to begin with. It was just not his Tamil. It is true that there was some extremely poor Tamil in the film, spoken by the actors playing Radha Aunty and Ammachi. But to his ears, it was all bad, all unintelligible.

“Our blood boiled when we heard those actors speak. We have a responsibility to save the image of our language!” The local liaison said this and versions of this to me more than once during this entire experience. But there he sat at the screening, saying “Huh, what’s that?” so often. Not knowing that some of what sounded right to him was in fact wrong. Left to themselves, the Indian Tamils would have completely erased any Ilankai Tamil dialect and replaced it with the kind of Tamil they found correct, in caricatured accents at best. He mentioned some of the Indian Tamil actors that Mehta had wanted to hire for certain roles, not understanding my point that that was no different from hiring Sinhala, North Indian and Pakistani actors, as ultimately happened.

“We wouldn’t say badrama poitu vaanga; we would say kavanama poitu vaango. We wouldn’t say mudiyathu; we would say ela. We wouldn’t say paiyan; we would say podiyan,” I said all this and more. He was flummoxed by one of our most common terms of endearment. (“It’s mahen,” I said. It means son.). That word, which I correctly pronounced out loud in that studio although the actor playing Appa hadn’t, was an emotive trigger for me. I thought of my uncle-not-by-blood, my dearest uncle, who had passed away in Colombo not even a month before. That was how my grandparents had always addressed him. I thought of my grandfather who still had not been told that his mahen had died. I thought of my people, and all we had been through. I had tears in my eyes during the two riot sequences in the film. I felt deeply alone in that experience because I was the only person in the room who was having that experience, of having scenes evoke loved ones and certain memories.

I was moved by the film, and was invested not in “saving Deepa Mehta” as the liaison described it, but in mitigating the dissonance of the jarring Tamil dialogues so that another Ilankai Tamil person viewing it could see one of our stories depicted with more accuracy, even despite the lack of representation.

When the screening ended, the liaison started talking about what to do next, within a deadline of five days. I found myself having to interject and offer my thoughts. I had been under the impression that I had been invited so they could learn from my opinion, but I was not asked for it. I slowly began to realise that I had been invited on an assumption that I would fall into line with a pre-decided mission. He wanted to have local actors dub the Tamil lines, had even identified some already, and wanted me to coach them for authenticity. My feedback was not actually required, only my assistance to his plan. At one point, he proposed getting Indian Tamils together to speak in support of the film, to which I said point blank to all present at the studio: “Indian Tamils have always exploited the Sri Lankan Tamil cause.”

Over a series of phone calls over the next day and a half, each increasingly frustrating, I relayed to him my complete feedback. The critique over the casting was absolutely valid but clearly impossible to fix at that late stage. Given this, my input was that it was imperative to hire Ilankai Tamils to dub the roles in which the Tamil was particularly flawed. I told him I would not personally coach Indian Tamils, because this was further erasure, and it would not bring in the authentic representation that was missing into the film. My view was that hiring any new non-Ilankai Tamil voice artist to perform an accent was wrong. I iterated repeatedly that the issue was not technical but sentimental and cultural. I asked: “Do you want to address why Ilankai Tamils are upset, or do you just want to make sure that Indian Tamils don’t laugh at the film on Twitter?”

I believed that the only thing that could be done was to have authentic Ilankai Tamil voices — literally — in the film. They wanted to prioritise how many, due to the time crunch. I felt that only two roles, Radha Aunty and Ammachi, needed a complete redub. I went as far as to offer two practical forms of assistance: wherever else the original actors could be minimally coached, I was happy to send voice notes they could learn from (I did ask why Colombo-based actors couldn’t just consult friends and family), and offered to personally dub over the worst vocal performance, that of the character of Radha Aunty, if that could help them meet limitations of time. I insisted they would have to find someone of the right background to dub Ammachi, from somewhere in the world. I also felt that it would be an insult to dub the voice of the character of Amma, who was essayed by a half-Tamil (half-Sinhala) actor, the only Tamil in the entire principal cast. Despite her imperfect enunciation, denigrating the actor’s command of her mother tongue would also be a kind of erasure. All Ilankai Tamils today are from traumatised communities, and our fluency and accents change depending on our exposure, education and even who we talk to. I once listened to an Ilankai Tamil poet who lives on the island, and writes in the language, speak in Chennai Tamil to an Indian Tamil audience. Was he pandering to them, or was he just nervous? I’m not sure. Code-switching is its own essay.

I noticed that crowd scenes in Funny Boy, shot in Colombo, had extras speaking Chennai Tamil. How could that have happened? The theory was that those hired were imitating Kollywood movies. Yes, entirely possible. But if so, where were the Tamil speakers on the set with the authority to rectify this, and say: “This scene takes place in Colombo in 1983. Please speak naturally”? Again, the overall insensitivity to the importance of language in this film is a serious problem, worsened by how it is officially a Tamil language film.

Any film is a collaborative project. There were so many hands in this one, but not nearly enough of ours. Even in this 11th hour consultation, they had outsourced damage control to India, where their delegates, at least up to the end of my involvement, sought only one authentic opinion — mine. What would have happened if there had been more Chennai-based Ilankai Tamils at the screening? Would our thoughts and contradictions have been summarily dismissed because — as I was told at one point — “You people are very divided”? I had responded to that: “We are diverse.”

I do not include anything the liaison, the local Tamil filmmaker, claimed that either Mehta or her collaborators had said to him because I simply cannot ascertain the veracity for the same. I also do not know what he conveyed to them from my inputs. I have not addressed issues raised regarding Mehta’s alleged closeness to the Sri Lankan government because I’m not sure how to, and get the sense I don’t know enough. Is she actually friends with the leaders or did she meet them so as to oil the wheels for bureaucratic permissions, and how have her views evolved in the time since her earlier productions were filmed there? But I know this is a crucial part of the critique for some Ilankai Tamils, and it would be remiss of me not to acknowledge it. This being the case, Mehta is obliged to address these issues.

I don’t know anything about what Mehta thinks because the liaison did not permit me to speak directly to her or even to her trusted collaborator in Chennai, although I strongly insisted on this. I recognised that some industry hierarchies were at play, so repeatedly requested that I at least be connected to Mehta’s friend, who could relay to her what the liaison didn’t want to. When confronted about why I wasn’t included in discussions with either, the excuse of “Oh, it happened in a rush” was all I was given. I did tell him that despite my other recommendations, the best thing to do was to let the producers know that it wasn’t within their outsourced team’s resources to handle the last minute mitigations, and that they should contact Ilankai Tamils who could. I also questioned why they wanted to tamper with the finished product at all, knowing that the worst of the damage could not be fixed. What was really going to be gained from this late stage Indian intervention, and for whom?

In the final phone call, things escalated.

“[Mehta’s friend] and I don’t want to get into the politics of this…”

I told him that the moment they touched this mess, they had already become involved in the politics, that the film was inherently political, and to understand their own cultural position in relation to the same.

He had told me earlier that he knew only two Ilankai Tamils: myself, and another woman whom he didn’t want to engage with because he claimed she was vociferous in her view. I was literally the only Ilankai Tamil person enlisted in this damage control endeavour in Chennai, and the only one whom any of them seemed to know.

“See, there are four kinds of Sri Lankan Tamils,” he began at one point. “The first, they are extremists…”

“Stop, stop right there,” I said. “I’m not interested in hearing your stereotypes.”

Racism wasn’t the only problem (yes, Tamil-on-Tamil racism). He then began to defend cultural appropriation, citing examples from his own forthcoming productions and existing movies by others, talking over my point that there is plenty of critique about exactly this. The moment of no turning back was after he said, condescendingly, “At the end of the day, we are making a film here.”

“This is a film to you,” I said. “It is a document and a testimony to the community. So if you say it’s just a film, then you’ve disrespected me and you’ve disrespected my community.”

But I had seen what I needed to: an up-and-coming director eager for the glory of being tagged as a collaborator of a renowned one, roping in someone whom he thought would do him a favour. He had no regard at all for the concerns of Ilankai Tamils, despite his bravado. I was angry but not surprised. Rare is the Indian Tamil who really cares. We are just like Che Guevara T-shirts in the Western world to them. There will be Indian Tamils reading this who feel indignant, especially if they have Ilankai Tamil associates, to which I say — that’s the premise the liaison was operating on too.

Let us return to that point about whether Ilankai Tamils identify with Indian Tamils beyond superficial ways. The answer is probably not, but maybe. It need not be a definitive answer, and it can change, and as more erasures happen, it will. But what is definitive is this: Indian Tamil identification with Ilankai Tamils is an act of usurping. It is not just culturally appropriative, but participatory in erasure. We are communities (plural, yes) who have suffered immense indignities and loss in our homeland. Indian Tamils have and exert hegemony over all other Tamils, and need to become cognisant of how they play into oppressor roles. They are not a monolith, either. But that is how hegemony works, spreading a long shadow and swallowing everything with proximity to it.

In 13 years of living in India as an Ilankai Tamil, I have experienced this appropriative, sometimes exploitative, erasure vividly. The experience that triggered this piece is not at all unique, and is in fact the norm. I have known that my moments of anger pale in relation to the true cost. This privileged experience of mine, of having a private film screening held for me despite being treated as a token, is the least of it. Who do you think takes the brunt of performative pro-Tamil activism in India? Tamils on the island, that’s who. This is why I don’t feel attached to Indian Tamilness, despite my domicile and my connection through half-parentage.

When Indian Tamils imitate a natural Ilankai Tamil accent in conversation, thus caricaturising it and making the speaker self-conscious, it is an act of violence. When a dialect is “corrected”, it is an act of violence. When an accent is sexually fetishised, it is an act of violence. When an attempt to code-switch to the local dialect so as to fit in, after having been shown that one’s natural dialect would be treated as an amusement, is also laughed at, it is an act of violence. When a beach frolic vacation across the Bay of Bengal is casually suggested by an Indian Tamil without any thoughtfulness about a diasporic person’s own journey of leaving and sometimes not having been able to return to the island, it is an act of violence. When India loses or wins in an international cricket match and a nasty forward about the island’s people, followed by an “oops, didn’t mean to send that to you”, is received, it is an act of violence. When an Indian Tamil author writes a self-glorifying paean to militants, and shuts down commentary from those who lived the experience, it is an act of violence. When May 18 (Mullivaikkal Remembrance Day, commemorating the official end of twenty-six years of conflict) comes around and social media is full of Indian Tamils basking in vicarious victimhood, it is an act of violence. When Indian Tamil liberals willfully skip across information about the LTTE’s treatment of its own and others, it is an act of violence. When an Indian Tamil translator selects only work that doesn’t complicate the narrative of Ilankai Tamils as victims, as mutilated bodies, as the disappeared — shying away from any story in which we thrive, love, live anyway — it is an act of violence. When an Indian Tamil politician orates on the plight of Ilankai Tamils in order to secure votes for themselves through playing up superficial identifications, it is an act of violence. When Indian Tamils say better them than an Ilankai Tamil who doesn’t speak the language or who hasn’t been to South Asia, with no regard for how that came to be, it is an act of violence.

Every one of these examples is real. There are no hypotheticals here — except the giant hypothetical mass of Ilankai Tamils in the Indian Tamil consciousness. There is a lot of love in Tamil Nadu for the emotional crest of the idea of our suffering (which inspires a part-valorous, part-victimised and entirely co-opted “pride”), and of us as tropes. But there is not much space at all for our actual complex, thriving selves, or our cultures, or the ways we speak our language. We are assumed to be the same because we are not accepted as being different, except as curiosities. If this were untrue, I would be able to engage in life in Tamil Nadu as my whole Tamil self, not a neutralised rendition of the same. I cannot.

Indian Tamil conflation of Ilankai Tamil identities with their own is not a form of solidarity. Erasure, misappropriation and complicity in strife are the effects of the conflation.

To me, this is about a lot more than one rude event. But to return to Funny Boy and their strange decision to outsource damage control to India… Having been disrespected by the local liaison, who truncated our conversation just when I called him out and did not respond to a further message, I went rogue.

This liaison had set up a Whatsapp group to discuss the “technical issues” with the film (Remember: “The issue is not technical. It is sentimental and cultural.”). There were some Canadian numbers and some Indian numbers on it. I posted a message saying that the Canadian team could contact me directly if they wanted to have my inputs, which I did not feel had been fully communicated to them, and exited the group. Someone in the sound department reached out immediately. I voiced my concerns and offered my solutions concisely, making sure they knew that “There are inherent challenges to outsourcing to Indian Tamils anything that concerns Sri Lankan Tamils, and I am afraid you’ve run into the same in this situation”. Somewhere, I still wanted to help make the film be something that could matter to the people the story is about, among whom I count myself, and not just be a work of erasure. I was told my email would be forwarded to Mehta and the producers.

That night, the local liaison left a one-ring missed call, followed by this message: “Hey Sharanya, we finally found a Srilankan [sic] Tamil woman who is a dubbing artist”. “Glad to hear,” I texted back, not necessarily believing him. That was the last I heard from anyone associated with Funny Boy.

As I write this, the film is weeks away from release on Netflix and while a part of me thinks that I’ll be ready to revisit it and see what they finally chose to do, I suspect the sourness of the experience of being used will stay, and I won’t be able to. My response to the film was coloured by the way I was treated as a sensitivity consultant. I was never compensated in any way for my time, emotional labour and insight; not even my request that masks be worn in the air-conditioned studio, due to the pandemic, was honoured. Most of all: I was not heard. The blame for the way I was treated does not fall on Mehta directly. In fact, it is two degrees removed from her, as I was used in this tokenistic way by an associate of her associate. But the choice to outsource damage control to India to begin with, rather than to Sri Lanka where the production took place or to the Canadian Tamil diaspora to whom this film is closest as a sentimental object, had to have been a decision from the top.

My frustration and hurt aside, as a creator myself, I found the experience illuminating. Seeing firsthand how crucial information was being kept from the person who was taking all the fallout, withheld by the very people entrusted to support her, taught me something about creative dynamics. It is not my intention to try to absolve Mehta, who should have made sensitive casting choices within her power as director as well as taken the time long before public announcements to ensure that the language was accurate. Here, I want only to make a general observation about art-making processes. Our friends and collaborators may not tell us what we need to know. Opportunists and yes-men who want to ride on our coat-tails benefit from our confusion or ignorance and won’t help us clear it. It is necessary for us to look beyond our circles, request constructive feedback, and make informed choices. We must dispel the notion that the buffer around us — of well-meaning but clueless well-wishers, people who are intimidated by us, some with secret resentments and others without a stake or real engagement — protects us. Sometimes it keeps us from seeing what we need to.

It is also entirely true that sometimes things just don’t fall into place in a project. Neither should a work of art be dictated by a current sociopolitical pressure point, at the expense of a meaningful final creation. So we must move forward thoughtfully, aware that blunders are always possible. I believe we can take them in stride gracefully if we attempt a different approach from either outright defensiveness or over-democratisation. As artists, we should move toward normalising not just the necessity for due diligence but also the necessity for pre-emptive disclaimers or apologies, which are cognisant of how we all operate within cocoons and logistical limitations, but that most of us try our best. I have tried to do that even now, as I write this. I cannot hold an objective view on everything I have described, and I can also be honest that something about this experience triggered me into speaking about Indian Tamil hegemony after years of biting my tongue. Almost all of this piece was written between 2am and 5am on the morning of November 10th, not initially in order to publish, but only so as to process this experience. It is what it is: an outpouring. I have not presented some perfect treatise. I have only presented a perspective.

Finally: I do not think Deepa Mehta’s Funny Boy needs to be boycotted, as some have encouraged, although I understand and respect why some will. Having seen the film, I can say that the one hour and forty nine minutes of its world contain an important story. It is a story of genocide, but also a story with joy, comfort and tenderness in it, and so it presents another possible rendition of Ilankai Tamilness — even if it is representationally inadequate (and it is).

The colossal mistake of not having enough Ilankai Tamil talent in a film about Ilankai Tamils cannot be fixed, but the film as a work that expands artistic representation of us was something I believed in, and mostly still do. My definition of “enough” is that more, perhaps at least half, of the actors on the principal cast should have been Ilankai Tamil; others will have different ways to measure what fair casting would have meant. I also believe that more amends must be made after the release, including to highlight queer Ilankai Tamil people in the diaspora (I hesitate to say on the island, because of vulnerability due to laws). Many have raised this point, and Vinsia Maharajah lists some creatives here. Additionally, those behind this film — all of whom are in positions of relative power systemically and otherwise — are obliged to speak publicly about realities for Tamil people and people of all minorities in present-day Sri Lanka, but only in close consultation with organisations on-the-ground who are engaged with healing and social justice work.

For better and for worse, this film adaptation of Funny Boy is not our only story. Whether or not one chooses to boycott or to watch it, from the mess of how this beautiful and flawed movie was made, let us learn. Not only to take more strides with our own tales, but above all else, to keep learning how to do the thing that not enough people at any stage of this film’s journey seem to have wholly done — which is how to listen better. The antidote to the fear of cultural appropriation is neither cautious silence nor dismissing the concern; it’s just listening, and having the grace to be clear that one can only paraphrase, and never speak for another.