by Sachi Sri Kantha, October 24, 2012

The Hindu’s collection of mish-mash tributes

Previously, I did contribute a short item entitled, ‘Requiem for G. Kasturi (1924-2012)’. Kasturi’s influence on the Eelam issue deserves a more in-depth look. As such, I continue my appraisal further. The editorial team of the Hindu (Chennai) daily had gathered a mish-mash of ‘tributes’ to Kasturi, in its internet edition. I provide a select list of items that appear in this collection.

A giant of journalism – by MarkandeyKatju

Visionary who set The Hindu on modern path – by a Special Correspondent

Passion for photography – by D.Krishnan, photo editor of the Hindu

A complete professional, modest to the core – by K.K.Katyal

‘Kasturi made me a daring journalist’– by C.V.Gopalakrishnan

A photo feature on G. Kasturi

The Complete Editor – by V.Kalidas

Sport was more than a pastime for GK – by S.Thyagarajan

Remembering ‘GK’– by K.Narayanan

I consider this as a bizarre tribute, for the main reason that we are not served with a sample of the best writings of Kasturi, who held the longest tenure as the editor of the Hindu. Here are some of my questions. If he was a hands-on, active editor, then who wrote all the editorials that appeared regularly during his tenure? Was there a ghost-writer for Kasturi? Why not present some of Kasturi’s most influential editorials which made history? What was his political hue and bias? Was he a weather vane? When Indira Gandhi declared emergency in 1975, what did Kasturi write? Did he stand up to her with a straight chest, or did he bend his neck for tactical and survival reasons? During Kasturi’s tenure, how was the ‘news’ reported? Was it given a fair treatment? Or was it dyed and twisted to serve the interests of the House of Hindu?

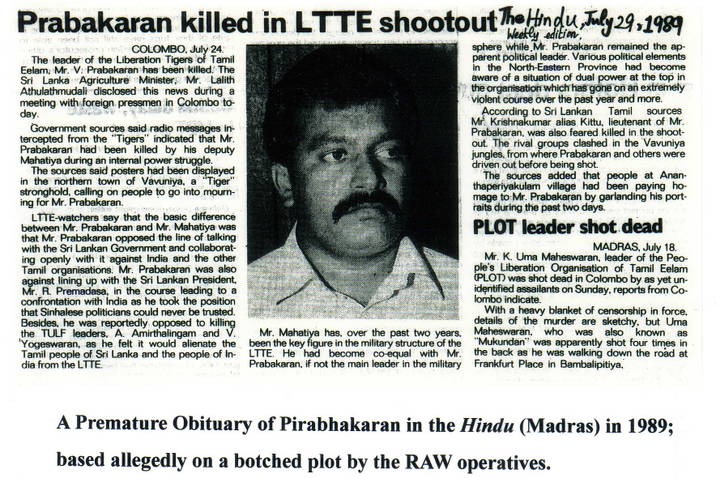

We should not forget that it was when G.Kasturi was at the helm, that the Hindu published a premature obituary of LTTE leader Prabhakaran in July 1989. It was one of the biggest blunders in the history of Hindu’s 110 years of journalism. Those who sing elegy toKasturi wouldn’t like this to be reminded. A responsible editor would not have permitted this sort of attention-grabbing gimmickry to adorn his newspaper’s pages, even at the insistence of nation’s gumshoes for whatever reasons. But, it did happen during Kasturi’s time!

The Hindu’s version of History

In 2003, when the Hindu celebrated its 125th birth anniversary, on September 13, 2003, it published its version of history, ‘Looking back’ in five sections. The sections were enticingly titled; (1) Willing to strike and not reluctant to wound, (2) Making News the Family business, (3) A Clarion Call against the Raj, (4) Treading Softly – but Modernising Apace, (5) Developing a Paper for a New Reader. Many ardent Indian freedom fighters would be chagrined to learn that the Hindu sided with the freedom fighters (section 3 caption)! This was a bold-faced lie. It had been the adopted policy of Hindu to side with the rulers.

I focus on section 5, which covers the tenure of G .Kasturi, and also devoted a paragraph to its editorial policy during the Indo-LTTE war period.Kasturi’s contribution to the paper was evaluated as follows: “G.Kasturi became Editor in September 1965. He had been working closely with his uncle and the various outstanding journalists who served the newspaper. A keen sportsman, who showed a flair for both tennis and cricket, he gave up these pursuits in single-minded dedication to the newspaper. Much of Kasturi’s time was spent on finding ways and means to reach the Hindu not only to the largest number of readers in the South but also to make it reach further and give meaning to its claim to be a national newspaper. The Hindu has always been a pioneer in technology and always paid close attention to management. Kasturi was the most technology-oriented of its editors ever…”

To be fair, the following was also recorded marginally: “The 18 months of the Emergency [during 1975-77] were not the Hindu’s happiest hour. Not once during that period did it oppose the Emergency or even its prolongation. It welcomed the ‘discipline’, even though it may be by punitive threat, in educational institutions, factories and government offices…”

To be fair, the following was also recorded marginally: “The 18 months of the Emergency [during 1975-77] were not the Hindu’s happiest hour. Not once during that period did it oppose the Emergency or even its prolongation. It welcomed the ‘discipline’, even though it may be by punitive threat, in educational institutions, factories and government offices…”

Then, on the Eelam issue, the stance Hindu took during the 1980s was scribbled with oozing anti-LTTE bias. To quote, “In 1983, the ethnic explosion in neighbouring Sri Lanka had the paper suddenly wake up to a situation brewing in the island from 1945, sizzling in 1956 and simmering till the pressure build-up led to the explosion. In the half decade that followed 1983, N. Ram, the paper’s associate editor, sympathized with the Tamil militants as well as the moderate Tamil United Liberated Front (sic). The newspaper’s reports as well as editorials made this clear. The Tigers’ turning on the Indian Peace Keeping Force, the heavy casualties suffered by the Indian soldiers in the North and East of Sri Lanka, the withdrawal of the IPKF from the island in early 1990 and the Tigers’ policy of assassinating any leaders opposed to it, resulting in Rajiv Gandhi’s calamitous death in a suicide bomb blast near Madras in 1991, all made not only Ram, but also the Hindu take a strong anti-LTTE line. In this sense, the newspaper mirrored official India’s policy course and turns.”

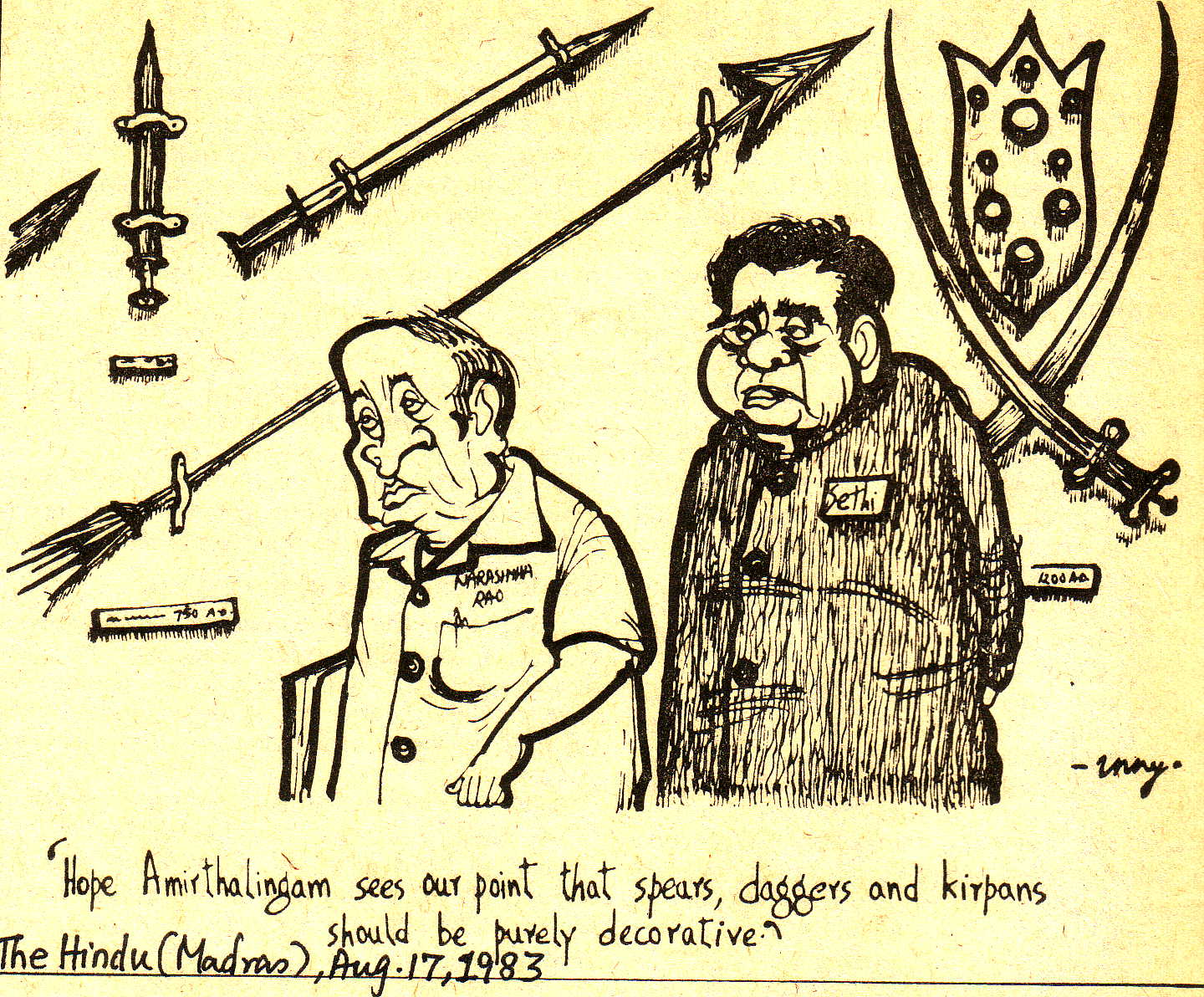

Well, let me comment on this slanted version of Hindu’s history writing 9 years later. The support provided by the Hindu for the Eelam Tamil cause stopped in 1983! Evidence: check the cartoon it published on August 17, 1983, which I provide nearby. The last sentence quoted above, indicates this clearly. In defending its anti-LTTE line, historians of the Hindu deftly place the cart before the horse. The Hindu is silent on the nefarious activities perpetrated by Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) operatives. Why did RAW promote a pot-pourri of ‘not for good ’Tamil militant groups since 1983? With the exception of Alfred Duraiappah murder that happened in 1975, most of the LTTE assassinations occurred after RAW’s promotion of multiple Tamil militant groups since 1983. Even the assassinations of TULF leaders, V. Dharmalingam and M. Alalasundaram in 1985 were carried out by the TELO (a group which was favored by the RAW) operatives and the blame passed onto LTTE. If LTTE had “assassinated any leaders opposed to it”, these anointed leaders (SLFP promoter Alfred Duraiappah, TELO leader Sri Sabaratnam and EPRLF leader Padmanabha for example) were killed for their treachery to the Tamil cause. LTTE was not an exception to any insurgent rebel groups all over the world. I had previously indicated that Nelson Mandela’s MK and even Yasir Arafat’s PLO had indulged in this extreme treatment of their adversaries of same blood. And, Mandela and Arafat were Nobel peace prize laureates! I do not consider that the assassinations of A. Amirthalingam and V. Yogeswaran in 1989 were perpetrated by the LTTE. It was planned and executed by the RAW gumshoes in collusion with the Mahattaya group (who had drifted towards the RAW). Not only insurgent rebel groups, even legitimate government agents do indulge in this sort of ‘skull-culling’. Would you care to check with the CIA (USA), MOSSAD (Israel) and RAW (India)? There exists prima facie evidence for the RAW-induced death of LTTE leader Col. Kiddu in 1993.

Well, let me comment on this slanted version of Hindu’s history writing 9 years later. The support provided by the Hindu for the Eelam Tamil cause stopped in 1983! Evidence: check the cartoon it published on August 17, 1983, which I provide nearby. The last sentence quoted above, indicates this clearly. In defending its anti-LTTE line, historians of the Hindu deftly place the cart before the horse. The Hindu is silent on the nefarious activities perpetrated by Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) operatives. Why did RAW promote a pot-pourri of ‘not for good ’Tamil militant groups since 1983? With the exception of Alfred Duraiappah murder that happened in 1975, most of the LTTE assassinations occurred after RAW’s promotion of multiple Tamil militant groups since 1983. Even the assassinations of TULF leaders, V. Dharmalingam and M. Alalasundaram in 1985 were carried out by the TELO (a group which was favored by the RAW) operatives and the blame passed onto LTTE. If LTTE had “assassinated any leaders opposed to it”, these anointed leaders (SLFP promoter Alfred Duraiappah, TELO leader Sri Sabaratnam and EPRLF leader Padmanabha for example) were killed for their treachery to the Tamil cause. LTTE was not an exception to any insurgent rebel groups all over the world. I had previously indicated that Nelson Mandela’s MK and even Yasir Arafat’s PLO had indulged in this extreme treatment of their adversaries of same blood. And, Mandela and Arafat were Nobel peace prize laureates! I do not consider that the assassinations of A. Amirthalingam and V. Yogeswaran in 1989 were perpetrated by the LTTE. It was planned and executed by the RAW gumshoes in collusion with the Mahattaya group (who had drifted towards the RAW). Not only insurgent rebel groups, even legitimate government agents do indulge in this sort of ‘skull-culling’. Would you care to check with the CIA (USA), MOSSAD (Israel) and RAW (India)? There exists prima facie evidence for the RAW-induced death of LTTE leader Col. Kiddu in 1993.

Five editorials on the Eelam Issue

As an Eelam Tamil, I was interested in how the Hindu treated the news originating from the island since 1983. As such, I focus on this angle and provide (in appendix) the five editorials that appeared in the Hindu, when Kasturi was at the helm, until 1991. These were in my collection. Though these editorials were unsigned, I assume that they originated from his pen. If they were written by someone else (such as N.Ram, for instance), at least Kasturi would have given the final approval before its appearance.

The first one appeared in May 17, 1984, in the aftermath of the kidnapping of American couple (Allens from Ohio) by the military wing of EPRLF. It need not be mentioned that the leading guy who perpetrated this act was none other than Douglas Devananda. At that time, the Indian prime minister was Indira Gandhi. While rapping the Sri Lankan government and its then imperious Minister of National Security, the editorial sided with the Eelam Tamils stating, “India cannot obviously be indifferent to developments in Sri Lanka which affect in a big way the Tamil people and the regional political situation.” Later, it turned out that the support offered by the Hindu was nothing but facile.

Other four editorials which appeared in 1988 and 1989 were biased against the LTTE, chiefly because LTTE was fighting against the Indian army sent by the then Indian prime minister Rajiv Gandhi. In my view, the relevance of LTTE’s war against the Indian army (1987-90) deserves exhaustive coverage, in view of the recent breast-thumbing parades and pronouncementsmade by the Sri Lankan military officials over their defeat of LTTE in 2009. While Sri Lankan army generals of the day cringed in fear of tackling the Indian army when demanded by their Commander in Chief R. Premadasa, LTTE and Prabhakaran stood up to the bully. None in the Sri Lankan military hierarchy can boast that they thumped the nose of the Indian army.

I bring to light five Hindu editorials of the pre-internet era for electronic record. My critique is as follows:

Chief Gripe of the Hindu against the LTTE

When we digest the four editorials which the Hindu published during 1988 and 1989, the chief gripe the Hindu had against the LTTE was that LTTE militants did not take the Indo-Sri Lanka (Rajiv-Jayewardene) agreement seriously. The dilemma with the Hindu editorialist (I guess, it was Kasturi) was that he totally ignored the other prominent political players who were against the Rajiv-Jayewardene agreement in his analysis. Even within the then ruling UNP, the second in command R. Premadasa and the imperious LalithAthulathmudali did not support the agreement. The SLFP, the main opposition party, to which the current President MahindaRajapaksa belongs to, did not support the agreement. Apart from the JVP, even the politically influential Buddhist clergy opposed the agreement. Nominally, these Sinhalese groups were ‘non-violent’, as opposed to the ‘violent’ LTTE. How much faith the Hindu had placed on these Sinhalese constituencies that they were willing to change their mind, at the instant when LTTE would forego its opposition to the Rajiv-Jayewardene’s ill-fated agreement? The simple truth was that, given the opposition generated by the Sinhalese constituencies, the Rajiv-Jayewardene agreement was doomed to failure at the instant when it was signed in July 1987.

The Hindu editorialist also had totally covered the bottoms of the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) operatives, by ignoring their nefarious roles in creating dissension among the various Tamil militant groups and also between the Hindus and Muslims in the Eastern Province during 1987 and 1990. I challenge any member of the Hindu editorial team (past or present) to show us one single editorial in which these lowly desperadoes and their handpicked Tamil militant group (EPRLF) and the Tamil National Army (TNA) had been condemned for their criminal activities in Sri Lanka.

Editorials 4 and 5 that I reproduce below (which appeared on April 29, 1989 and August 5, 1989) are very relevant for historical reasons. President Premadasa issued a unilateral declaration on June 1, 1989 that the Indian army should leave the island by July 29, 1989. This placed the RAW operatives in a bind. To embarrass LTTE, they organized the assassination of Amirthalingam in July 13, 1989 using Mahathaya group recruits. Yogeswaran was a ‘collateral damage’ in army lingo. All three assassins were killed by Amirthalingam’s security detail. One of the assassins (Visu) was a key Mahathaya valet. Then, within a week, Uma Maheswaran (the leader of PLOTE militant group) was also knocked off. Following this, on July 24, 1989, LTTE leader Prabhakaran was ‘killed’ by Mahathaya, according to the premature obituary that appeared in the Hindu! And the Hindu editorial that appeared on August 5, 1989 (in its international edition) claims that Premadasa administration took “negative effects between mid-April and July 24”, and it was ‘defused by intensive diplomatic efforts’. The facts that had been hidden by Kasturi were that the so-called ‘intensive diplomatic efforts’ were carried out by (1) the RAW gumshoes on behalf of India, (2) S.Thondaman Sr. (then a senior Cabinet minister) and also by the (3) then Sri Lankan military bigwigs who refused to stand up to the order of their Commander in Chief!

The editorial 5 that I present also makes mention of a public opinion survey conducted by the Hindu, on the role of Indian army in Sri Lanka. About this survey, I did express my disappointment and it got published, as I had previously included in my ‘Requiem for G. Kasturi’ item.

S.Sivanayagam’s Critique

In a letter under the caption, ‘The Hindu and editorial decorum’, S.Sivanayagam (writing under the pseudonym, S. Kurushetran, Madras, Tamil Nadu) had critiqued in 1988 about how the Hindu had twisted the important news facts to smear LTTE, during the LTTE-Indian war. I quote the relevant passages:

“…There is another aspect which calls for greater concern, and that is the paper’s growing lack of decorum in the reporting of the news itself; a tendency that cannot do any good to a paper that had acquired an international reputation over the years. Comment is free, but facts are sacred in responsible journalism.

As an example of motivated reporting on the part of the Hindu, we present here the reports of the same incident carried in the Indian Express of Aug. 14 [1988], and in The Hindu of the same day. The Indian Express reported thus:

‘Colombo, Aug. 13 (AFP): Tamil rebels killed seven Indian soldiers and injured four in the first of two attacks on the Colombo-Jaffna rail link in north-eastern Vavuniya district on Saturday, a military spokesman here said. The Indian soldiers were clearing the rail track in Kankarayankulam village for the north-bound train when the rebels exploded a land mine, the spokesman said. The Jaffna train, which left Colombo on Friday night, reached Vavuniya town on Saturday morning and was waiting the all-clear signal to proceed when the incident occurred, the official added. In the second incident, guerrillas blasted the rail track in Mankulam town farther north, preventing the train from proceeding…’

In contrast, The Hindu version reads thus:

‘Madras, Aug.13. An attempt by the LTTE to blow up a fully loaded passenger train in Vavuniya sector was today foiled by the timely action of the IPKF. However, the IPKF lost six of its personnel when the LTTE blew up a culvert. An IPKF press release issued here said that the LTTE had planned to blow up a passenger train in Vavuniya sector and had placed four explosive devices on a culvert on the rail track, six kms, south of Mankulam. IPKF troops searching the track detected the explosive devices in time. The LTTE in panic blew up the culvert prematurely resulting in six casualties to IPKF personnel but the train was safely stopped at Puliyankulam and the passengers and the train were saved…’

The report was headlined – LTTE BID FOILED. According to the Indian Express report, and in the minds of all intelligent and objective readers, the sequence of events was very clear. The LTTE blew up the track, preventing the train from proceeding. The IPKF went to the spot to restore the track and in the process became victims of a LTTE-triggered landmine. It would be straining the credulity of Sri Lankan readers (both Tamils and Sinhalese) that the LTTE could be so foolish as to blow up a train carrying hundreds of Tamil passengers; to ask readers to believe that they are politically ‘intransigent’s is one thing; but to tell them that the LTTE is capable of crass stupidity is something which should be told to the marines. But the sad truth is,The Hindu would have succeeded in misleading lakhs of Indian readers who depend upon the paper alone for their information.

The tragedy of the Hindu is the tragedy of newspaper editors who allow themselves to be sucked into the decision-making processes of their governments! [Tamil Times, London, October 1988, p.12]

My verdict: Those who read the editorials presented in the Appendix can recognize that Kasturi posed as a wiseacre and his wishy-washy writing style was verbose, pretentious, repetitive, unimaginative and unrealistic to the aspirations of Eelam Tamils. Last but not the least, his written stuff was boring to read!

*****

Appendix: Five Eelam-related Editorials that appeared between 1984 and 1989

Editorial 1: India’s good offices at work

[Hindu, May 17, 1984]

The release unharmed of the young American couple kidnapped earlier from their Jaffna residence by elements claiming to belong to the military wing of the Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front (EPRLF) is a happy outcome, which provides fresh evidence of the seriousness and reliability of India’s good offices in respect of the Sri Lanka crisis. This has been acknowledged by the US Government and the nation expects it to be acknowledged, without bad-faith annotation, by Colombo. Among other things, the outcome makes nonsense of the repeated public speculation by the Sri Lanka Minister of National Security, Mr. LalithAthulathmudali, that Mr. and Mrs. Allen must have been spirited across the Palk Straits to Tamil Nadu. The attempt to implicate Tamil Nadu and India in this act of individual terrorism without paying elementary courtesy to the facts is not merely indicative of a mischievous attitude; it also serves to expose the character of Colombo’s handling of the situation in Jaffna and the other Tamil areas. For instance, one of the revelations made by the Allens is that after the kidnapping they were driven blindfolded to an ordinary house in Jaffna approximately twenty minutes away (by car) from their residence, and kept in a room with the windows papered over. Then the kidnappers and their agents were apparently able to operate freely in passing on ransom demands and other follow-up notes to the Government authorities, without being tracked. The mode of delivery of the hostages – reportedly in a jeep at the Bishop’s house in the heart of Jaffna even as the security forces were combing Tamil areas intensively – was also significant. Such details speak to the kind of popularity and rapport with citizens that the Sri Lanka Government enjoys in the Tamil areas.

The Governments of India and Tamil Nadu must be complimented on their level-headed, crisis-solving roles in this deplorable affair with a fortunate ending. The stakes in securing the relase of the kidnapped couple were quite high, since one wrong move might have proved fatal to two young innocent people and might have also brought about a diversion from the larger issues figuring in the Sri Lanka situation. While India must continue to take a firm line against acts of terrorism that whill give the Tamil cause a bad name, there is no need at all for it to fall into a defensive posture in relation to the insinuations hurled from Colombo. In fact, the time has come perhaps to tell those in authority in Sri Lanka who cultivate such feelings of hostility towards India where they get off. The large number of people of Tamil origin from Sri Lanka – estimated to be over 30,000 – are here not for the fun of it, or because of anything India has done to draw them away from their homes and their avocations in their own country. They are here because a wave of genocidal assaults and follow-up acts of hostility in which the State clearly had a hand made it impossible or unsafe for them to stay. Now, the whole point about India’s good offices is to clear the path – within the framework of respect for Sri Lanka’s sovereignty and territorial integrity and a commitment to a peaceful denouement – for a meaningful political dialogue among parties who would otherwise not be in a position to talk to each other. At this point it is no more and no less than that India cannot obviously be indifferent to developments in Sri Lanka which affect in a big way the Tamil people and the regional political situation. At the same time, its good offices can only promote an amicable solution, but cannot by reasonable personsbem mistaken for the solution itself. Mr. J.R. Jayewardene and others who matter in Sri Lanka must pay heed to these realities and cooperate in the undoubtedly difficult challenge of working out a fair and workable solution to the Tamil question – at this stage the foremost national question confronting Sri Lanka. If they do this, they will find themselves returning quickly to the approach and the line of thinking reflected in Annexure C worked out in detailed cooperation with the Indian Prime Minister’s special envoy, Mr. G.Parthasarathy.

Editorial 2: Sri Lanka – encouraging signs

[Hindu International Edition, June 11, 1988]

In the recent period, there has been a visible strengthening of the indications that the Indo-Sri Lanka Agreement is coming through on more than one front and also in a larger political sense – and, equally important, these indications are beginning to make a qualitative difference to perceptions. At a time when policy-making credibility has generally been lowered in the South Asian region, these positive – but still provisional – results can be seen by any serious observer to flow from the soundness of the bilateral, cooperative policy that the Accord represents and also from the firm resolve, political and professional, which has been displayed on both sides of the Palk Strait in the face of extremist, anti-democratic intransigence. The decent popular turn-out in the latest round of Provincial Council elections, and the healthily divided outcome, demonstrate that the track of seeing the Accord through in the face of violent and chauvinist opposition from both the Sinhala and Tamil political constituencies – has a real future. The ruling United National Party has, with this round, won control of six provincial councils – a new democratic experiment made possible by the Accord – but, hearteningly, the United Socialist Alliance which is firmly committed to the Accord has put up a very creditable political fight. The USA – a combination of four left parties forged through the vision and martyrdom of the SLMP leader and film actor VijayaKumaranatunga– has overcome political and organizational odds to emerge as a credible political alternative. The extent of opposition to the UNP, which has been in power in the island from 1977, is reflected in the provincial council election results. The latest results rub in the poit that the main opposition party, the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) headed by Mrs. Sirimavo Bandaranaike, made a major political blunder by keeping away from these elections. They also amount to calling the JVP’s bluff to a large extent, although complacency in the face of the violent challenge would, obviously, be most unwise. From the standpoint of India, the outcome looks encouraging because the fair turn-out and the relatively smooth conduct of these elections can be regarded as a kind of referendum on a vital feature of the Accord – and on the politics of adhering to Indo-Sri Lankan friendship and a strong bilateral commitment. This much can be asserted notwithstanding the deficiencies and flaws that affected the way these provincial council elections were conducted.

On another front, the performance of the Indian Peace Keeping Force deserves the highest commendation. The political debate in India continues to underestimate the tremendous military pressure the IPKF operations have put on the LTTE and also the significance of the quantities of weapons seized for the peace process. Operating under what looked initially like extremely inhospitable conditions, the IPKF (in any objective or fair reckoning) has altered ground realities in the main region of crisis (the North and East of the island) in a quite profound way. It might be too much to claim that the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eellam, generalled by the resourceful Mr. V. Prabhakaran, is close to being brought to its knees. The Tigers clearly retain at least a residual military capability and a substantial political influence. However, there can be no serious doubt that they have been tremendously weakened, for reasons which are perfectly obvious. They have lost not merely their major staging bases but also most of the sanctuaries; nowhere are they safe from the highly mobile strike capability of the IPKF; and they will face a quite hopeless situation if the present mode of hostilities continues much longer. It would be a serious political mistake to regard the Tigers as some kind of liberation movement capable of waging a form of inexhaustible guerilla warfare through winning the hearts and minds of the people; it would be equally unsound to write them off as a political force, or consider them ‘terrorists’.

The latest intensive campaign conducted by the IPKF in the Alampil area, some 120 km of real jungle, and in the outlying region in the mainland North is testimony to the military fact that nowhere is armed militancy secure from the reach of a clear-sighted professional force and there is no question of Gen. Kalkat and his men tiring in their role. (A protracted military campaign is not to anyone’s advantage but no artificial time-limits can be counted on either.) The basic mission of the IPKF is to safeguard a civilized Accord which offers the best chance the tormented people of the island have had for a peaceful and enduring solution to the ‘ethnic’ mess to which several actors have contributed over the years. The specific mission is to enforce the demilitarization of the ethnic conflict as an integral part of the Accord and this means an even-handed responsibility. The gains made by Indian soldiers on the ground have come through professional dedication and sacrifice, quick-footed combat capabilities, superior leadership and generalship and, very important, the ability to learn from the experience, including mistakes. Success in this task means narrowing – in a no-nonsense way – the military option to hold out against the principles of the Accord. This has undoubtedly happened on the ground or there would be no complaints of the kind heard in the most recent period from the militants. The gains made at the direct expense of the LTTE as an organization must not be read, superficially or tendentiously, as ‘weakening’ the cause of the Sri Lankan Tamil people who surely thirst for peace and a decent chance to carry on their lives and avocations. These military gains can be converted into a qualitative element which leaves the militants a fair opportunity to come to terms with India and the peace process. Here, the political policy-maker takes over from the IPKF and the imperative is to hold firmly, but in a generous-spirited way, to the two basic ground requirements for a political solution – (a) the armed militants who have been holding out for months against the peace process must hand over all their weapons and (b) they must commit themselves sincerely to a path of cooperation in implementing the Accord. For those brought up on the faith that political disputes can be settled through the barrel of a gun, these add up to a pretty tall order. However, if the two basic requirements are compromised or diluted in an attempt to find a quick fix, there is no chance of the Accord succeeding in resolving the crisis. With the going looking increasingly good for those supporting the Accord, the Tigers – and also other militants and intransigents of various shades, including those owing allegiance to the JVP in Sinhala country – would do well to take a new look at their options and make their choices before it becomes too late.

Editorial 3: Positive Opportunity in Sri Lanka

[Hindu International edition, Sept. 24, 1988]

The ceasefire instituted for a period of five days by India in the Northern and Eastern provinces of Sri Lanka is well timed and purposefully directed. It is linked with a political initiative in the form of a package of inter-related democratic measures, and it provides another positive opportunity to the armed LTTE militants – who have held out against the Indo-Sri Lanka agreement and the autonomy-and-peace plan – to come into the political mainstream by surrendering arms and participating in the provincial councilelections which are to be held within weeks to the newly merged Northern-Eastern province. It is relevant to note that the ceasefire does not come in the wake of any specific development relating to the negotiating track. It is India’s initiative which comes in a context of assessing that substantive results have been achieved on the ground by the IPKF operations and the overall situation is ready for a determined political effort. Mr. Jayewardene’s acts of proclaiming a merger of the Northern and Eastern provinces, as provided for in the accord, without insisting on the precondition of a total surrender of arms by the militants, his direction to the Election Commissioner to set a date for the remaining provincial council elections; ordering the release of Tamil detenus; and showing a willingness to take practical steps to give meaning to the upgraded status provided to the Tamil language in the island’s set-up are statesmanlike contributions to raising the level of political goodwill in the joint venture. There can be no doubt that the recent intensive thrust in a thick jungle sector of the Mullaithivu district has narrowed the military – as distinct from the political – option available to the militants. Although greatly weakened in fighting strength and material, the LTTE has demonstrated a resourcefulness and a toughness that underline the fact that it is very much a political force among the Sri Lankan Tamils – especially in the North. It is significant that attempts to implement the accord have not adopted the aim of ‘liquidating’ the Tigers. The limited-duration ceasefire – which could progress into a permanent ceasefire if the indications from the militants turn out to be positive – is all about sending the message to the LTTE and its leadership that, while the IPKF’s professional task is to rule out anti-democratic and brutal options, the solution to the crisis of ethnic relations in the island must, of necessity, be political. The Tigers must abandon apprehensions and suspicions about what is in store for them and must display a breadth of mind and a realism of vision that will make them cooperators in a progressive peace plan that should have come good many months ago.

Overall, the political situation in the island takes an interesting and uncertain turn with the nomination of the Prime Minister and deputy leader of the UNP, Mr. R. Premadasa, as the presidential candidate for a major contest which is to be held in December. The veteran of many a political battle in the second half of this century, Mr. Jayewardene, has decided to call it a day. The presidential contest – which will involve the redoubtable MrsSirimavo Bandaranaike, the former Prime Minister and SLFP leader, as the already announced challenger – promises to be eventful. This is to be preceded by provincial council elections in the Northern-Eastern province and be followed by long-delayed general elections to Parliament. The Indo-Sri Lanka accord will no doubt figure as a principal issue in all these contests. While the bilateral framework is strong enough to weather any change of government or leader in the island – in that there is no question of any unilateral action undertaken to abrogate or change the terms of the accord, which is in the nature of a permanent arrangement – there must clearly be a keen interest in achieving as much as possible during the presidency of the man who forged the accord with the Indian Prime Minister and has stood by it in the face of tremendous political and terrorist pressure. A political breakthrough on the ground in the North and East should go a long way in clearing up the picture in the island and in vindicating India’s role as a sound, and progressive one in a difficult context.

Editorial 4: A New Twist in Sri Lanka

[Hindu International Edition, April 29, 1989]

The political reality must be faced that the Premadasa administration in Sri Lanka is engaged in some kind of confused, but active and even adventurous exercise of wriggling out of the core political commitments that are laid down by the Indo-Sri Lanka Agreement signed by Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and the then Sri Lanka President, Mr. J.R.Jayewardene, on July 29, 1987. The other day, on a television programme produced by PTI TV and telecast by Doordarshan, Mr. RanjanWijeyratne, the island’s Foreign Minister who is also Minister of State for Defence, virtually announced that his boss was not with the Agreement and even suggested that this was the main reason for his relative success with the chauvinistic Sinhalese. The bilateral and political implication of this kind of statement of policy must be taken seriously. Unfortunately, the top policymakers in New Delhi appear to be giving the new developments, complications and nuances in the island less than concentrated attention and less than the priority they demand. The chief issues involved here are India’s long-term democratic and progressive interests in the region and, as a vital part of these, the position and honour of the nation’s armed forces which have been deployed in a tremendously difficult peacekeeping role in an alien arena. There can be no doubt at this juncture tht the IPKF has, through its tremendous endeavours and sacrifices, succeeded to a very considerable extent in weakening and containing the chief extremist and peace-wrecking factor in the region of its operations. In the most recent period, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (which, as a military proposition, is essentially bottled up in the Vavuniya jungles and has suffered major losses in resources and men, including reported injury to its deputy leader and talented general, Mr. Mahathiya) has reached out to Mr. Premadasa and to the norms and values on foreign policy matters that his administration represents. Responding to vague overtures from Colombo, the LTTE has publicly suggested that the two antagonistic Sri Lankan political players –one chauvinistic Sinhala, the other extremist Tamil – have a common interest today in moving India, and its interests and role, out of the arena. This is a very strange turnaround in the LTTE’s well-known intransigent course and it makes no sense at all except as an indicator or expression of a significantly weakened politico-military position imposed on it by the IPKF’s operations over time. Otherwise, there would be no rationality at all in the drama of uncompromising fighters for ‘Tamil Eelam’ repairing to the abode of their ‘national enemy’ in the openly expressed hope of doing a deal at the expense of India and its perfectly legal and legitimate role ensured by a bilateral Agreement which cannot be changed or altered unilaterally. (The slippery slope that the Tigers have travelled in their hunt for ‘Eelam’ can be indicated with reference to two dramatically different political signposts. On August 4, 1987, Mr. V. Prabhakaran, the LTTE chief, told his people: ‘I do have faith in the straightforward-ness of the Indian Prime Minister and I do have faith in his assurances…We love India. We love the people of India. There is no question of our deploying our arms against Indian soldiers. The soldiers of the Indian Army are taking up the responsibility of safeguarding and protecting us against our enemy. ..However, I do not think that as a result of this Agreement, there will be a permanent solution to the problem of the Tamils. The time is not very far off when the monster of Sinhala racism will devour this Agreement’. On April 11, 1989, the LTTE’s political committee said in an ‘open letter’ to Mr. Premadasa: ‘You may go ahead and mortgage the birthright of the Sinhala people. But we will not mortgage the rights of the Tamil people to anybody…Until the oppressive Indian Army leaves our land, there will be no such thing as a ceasefire. And after they leave, you will come to recognize that in the island of Ceylon there are two nations. And after that, we will need neither war nor ceasefire.’ The concluding note must be recognized as one of the more bizarre policy statements of recent months.

Official India has correctly made it clear that it has no objection to any talking exercise, and indeed wishes it well – provided the aims, objectives and content are in keeping with the Indo-Sri Lanka Agreement, which must be seen essentially as an instrument for helping the process of ending armed ethnic strife in the island and healing the deep wounds, for providing a decent measure of autonomy or devolution of power to the historically oppressed Tamils within the framework of Sri Lankan unity, and for taking care of India’s legitimate and democratic foreign policy interests in the region. But what official India must tell its own people clearly is that it has not been consulted fairly and constructively by Colombo and its concurrence cannot be taken for granted. India’s interests certainly call for a reduction of the heavy military burden and for the disengagement of the IPKF on a phased and deliberate basis (within a realistic time frame) but this doesn’t mean that the positive results of a yet-to-be completed process can be undone or messed up in the bargain. What New Delhi must make clear to Colombo at this tricky juncture is that the devolution package must be seriously and honestly implemented; that there must be no cheating or shortchanging on the exercise; that the elected Provincial Government led by the EPRLF and defended by the IPKF must be respected and strengthened in the enormous task it faces; that the possibility of any future ethnic strife targeting the Tamils must be credibly ruled out; and that India’s strategic concerns relating to the status and future of Trincomalee, the induction of mercenaries and so on in the island must be taken care of, as promised in the Agreement. Part of the challenge is bringing politico-military groups like the LTTE into the democratic mainstream and this must be understood to mean, especially in the light of the experience, that there are usually no easy options in historically mishandled situations. The Sri Lankan Government would do well to play straight with India, and the LTTE must realise that, even at this stage, it can come into the democratic mainstream – provided it decides strategically to give up arms and the desperate armed struggle, abandons the extremist goal of ‘Eelam’ and makes peace with the civilized objectives of the Indo-Sri Lanka Agreement.

Editorial 5: India and Sri Lanka – back on a good track

[Hindu International Edition, August 5, 1989]

The working agreement reached between the Governments of Sri Lanka and India to take up, in a friendly and cooperative format of discussion, the key issues on which discord had threatened to develop into a confrontation is vitally important. It is a political development which all those who place a high value on good neighbourliness, equality between nations, peace and justice will welcome wholeheartedly. The substance of the agreement is unambiguous. The unilaterally prescribed deadline of July 29 for the withdrawal of the IPKF ‘ in its entirety’ has now been withdrawn, very constructively, by the Sri Lankan President, Mr. R. Premadasa. The quid pro quo, as it were, for this is that the process of phased withdrawal of the Indian Peace Keeping Force – which was begun in a small way earlier in the year, even before President Premadasa made a formal request, but was suspended in response to his June 1 ultimatum – is now back on track. In other words, the removal of the totally unreasonable demand has unblocked the path for an event that must take place sooner or later (perhaps sooner rather than later if the socio-political and human circumstances are right). A major political and practical conclusion follows from this: the framework of the new bilateral understanding fully legitimates, from the standpoint of the Sri Lankan Government, the presence and operations of the IPKF in the North-Eastern Province under the terms of the Indo-Sri Lanka Agreement. With the factors of unilateralism, wild cards and unreasonable pre-conditions removed from the picture, at least for now, all the issues which figured in the recent disagreement between the two Governments are back within the bilateral, reasonably discussable framework represented by the Agreement. The substantive issues include the time-table for the phased withdrawal of the IPKF; the incomplete achievements of the Agreement, which means the positive gains as well as the problems that have arisen in the implementation; the unsatisfactory but not hopeless experience with the devolution of power in the North-Eastern Province; the safety and security of all communities in this region and, specifically, the safety and future of the Tamils who have suffered a great deal of injustice historically and badly need a break from the threat of gun-toting intransigence and extremist violence. People of goodwill in India and Sri Lanka will congratulate the two Governments on the achievement of averting a nasty confrontation and bringing the rapidly worsening problem in bilateral relations under rational control.

The challenge now is to take those principled and constructive steps which would help neutralize the negative effects of the path pursued in Colombo between mid-April and July 24, when intensive diplomatic efforts began to defuse the crisis. The memory of this regrettable chapter in Indo-Sri Lanka relations can be quickly erased – provided the opportunity presented by the decision to rule out confrontation and resume cooperation is seized intelligently in the New Delhi talks. On the Indian side, every effort must be made to convince the government and the people of Sri Lanka that this nation has the highest regard for the unity, integrity and sovereignty of its small neighbor and there is no question of wanting to do anything to impinge on these values. In this connection, the correct and principled call issued by the Left parties, in particular the Communist Party of India (Marxist), to the Indian Government to avoid adopting ‘any posture which impinges on the sovereignty of Sri Lanka’ is important to bear in mind during the current negotiations. Political India must also be sensitive to the severe constraints and risks the JVP factor has imposed on the Sri Lankan Government; it must make precisely those inputs that would strengthen the hands of democratic forces against the danger of an extremist or chauvinist takeover in the island.

In all this, the role of the IPKF in keeping alive the chances of securing peace and justice in the historically troubled North and East of the island – under very, very difficult and complicated circumstances on the ground – deserves the highest commendation from democratic and progressive-minded people in both countries. The results of the latest public opinion survey on Sri Lanka, conducted by The Hindu, reveal, most encouragingly for a policy-maker, that in Madras, a centre that is strategically and politically close to the problem, the decisive bulk of popular opinion appreciates the heroic IPKF role, firmly disapproves of the course of extremist intransigence, supports the thrust of the Government of India’s policy and favours a course of sobriety and, perhaps, also political generosity. If the bilateral discussions go well and if agreement is quickly reached on all the sensitive issues – the content of the devolution exercise, the safety of the Tamils, the state of democratic play in the North-Eastern Province and the status of the Indo-Sri Lanka Agreement – then both countries could move together to take those necessary steps which would bring about a durable cessation of hostilities in the North-Eastern Province on the basis of reliable assurances and arrangements. Such a development would facilitate talks involving all the relevant parties, the two Governments and all the Tamil political organisations, including the LTTE. This is yet another opportunity for Mr. V. Prabhakaran’s militant organization to take those difficult, against-the-gran decisions which would make it unnecessary for anyone to go after its cadres and accomplices in a military sense. If the LTTE commits itself to a course of coming into the democratic mainstream – which would include the propositions of giving up the path of violence, allowing other political organisations to function in a democratic environment, accepting the unity and integrity of Sri Lanka and ceasing to treat the IPKF and India as the enemy – then the ‘ceasefire’ it has asked the Sri Lankan Government to wrest from India could be obtained for the asking overnight. Once that happens, and the relevant assurances and institutional and political arrangements are firmed up between the two Governments, the process of IPKF withdrawal could be accelerated and the timetable handled in a manner that would brook no suggestion of discord or controversy. This is the outcome that democratic-minded people in both countries should work towards.

I think this writers verbose article can be squeezed into a tiny nutshell thus. Kasturi, is a traitor for opposing our LTTE!

Well, it seems Kasturi did not appreciate the LTTE spoiling Indo-Lanka accord. How many Tamils would disagree I am thinking. Didn’t LTTE engineer the Jaffna hospital massacre and the Theleepan fast in order to scuttle the Indian backed peace process? This was not first time I might add. They would do it again in 2002. By this time of course the amendment had already entered the constitution. Therefore it seems even if there were opposition by the Sinhalese, their leader did make an attempt to solve the problem. Am I wrong here with my own critique of this author?